These Powerful Posters Persuaded Americans It Was Time to Join the Fight

The Smithsonian offers a rare opportunity to see an original iconic Uncle Sam “I Want You” poster, among others, of the World War I era

Woodrow Wilson was re-elected in 1916 on the slogan “He kept us out of war.” But just a month after his second inaugural, on April 6, 1917, he signed a declaration of war and the U.S. joined World War I. A week later, he went to work on selling the idea to the public through the creation of the Committee on Public Information.

Through its Division of Pictoral Publicity, an unprecedented advertising blitz of memorable posters were created by some of the top illustrators of the day. Some of that work is collected in an exhibit, entitled “Advertising War: Selling Americans on World War I” and now on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

It includes some of the most enduring images of that poster campaign, as well as some of the lesser known, such as one declaring “Destroy This Mad Brute—Enlist” showing a raging gorilla in a Kaiser’s helmet crossing into America and grabbing a helpless woman.

Best known of the group is James Montgomery Flagg’s depiction of Uncle Sam pointing directly at the viewer: “I Want You for U.S. Army.”

That iconic pose had its roots in British posters dating back a few years to the beginning of the conflict, according to David D. Miller III, a curator in the division of armed forces history, who organized the display from the museum's holdings of more than 600 posters.

“That pose was from a sketch of Lord Kitchener, who was the British Secretary of War, who did a similar thing,” Miller says. The famous UK 1914 poster shows Kitchener pointing his finger, says “Britons Want You: Join Your Country’s Army.”

The Kirchner poster is not in the exhibit, but another one inspired by it depicts England’s own Uncle Sam-like character, John Bull, a Union Jack across his belly, pointing to the viewer, with the caption “Who’s Absent? Is It You?” to encourage enlistment.

Flagg, for his part, “did a self-portrait of himself in that pose, and added the beard and white hair and Uncle Sam costume to it,” Miller says.

So the image most of us have of Uncle Sam is that of the illustrator Flagg, imagining himself an older man in white hair in beard. “He was a much younger man at the time, but as he grew older, he came to very much resemble that ‘I Want You’ poster,” Miller says.

An original sketch of the poster, millions of which were made, is in the exhibit, but will have to be subbed out in a few months in order to protect it from further light damage.

“It’s already color-shifted terribly and we don’t want it to get too much worse,” Miller says. “Instead of red, white and blue, it’s kind of green and brown.”

The second best known poster in the lot is probably Howard Chandler Christy’s portrait of a young woman, seeming to wink as she says, “Gee!! I Wish I Were a Man. I’d Join the Navy.”

Christy became known before the turn of the century for his drawings of Theodore Roosevelt at the Battle of San Juan Hill, Miller says. “But after the Spanish American war, he said, ‘I’m sick of that now, I’m going to concentrate on beauty,’ and he did sketches and portraits of women.”

Already known for his Christy Girl illustrations in The Century magazine, he put a woman in the Navy recruiting poster, which was believed to be one of the first to try to recruit with sex appeal.

“The funny thing about that is that he had two different models who did Navy recruiting posters and both of those women joined the Naval reserve,” the curator says.

The role of women was also pronounced in World War I, with 13,000 women in the Navy and Marines; 20,000 in the Army and Nurse Corps, and nearly 1 million joining the workforce.

One poster supporting the Y.M.C.A. Land Service Committee to encourage agricultural work declared “The Girl on the Land Serves the Nation’s Need.”

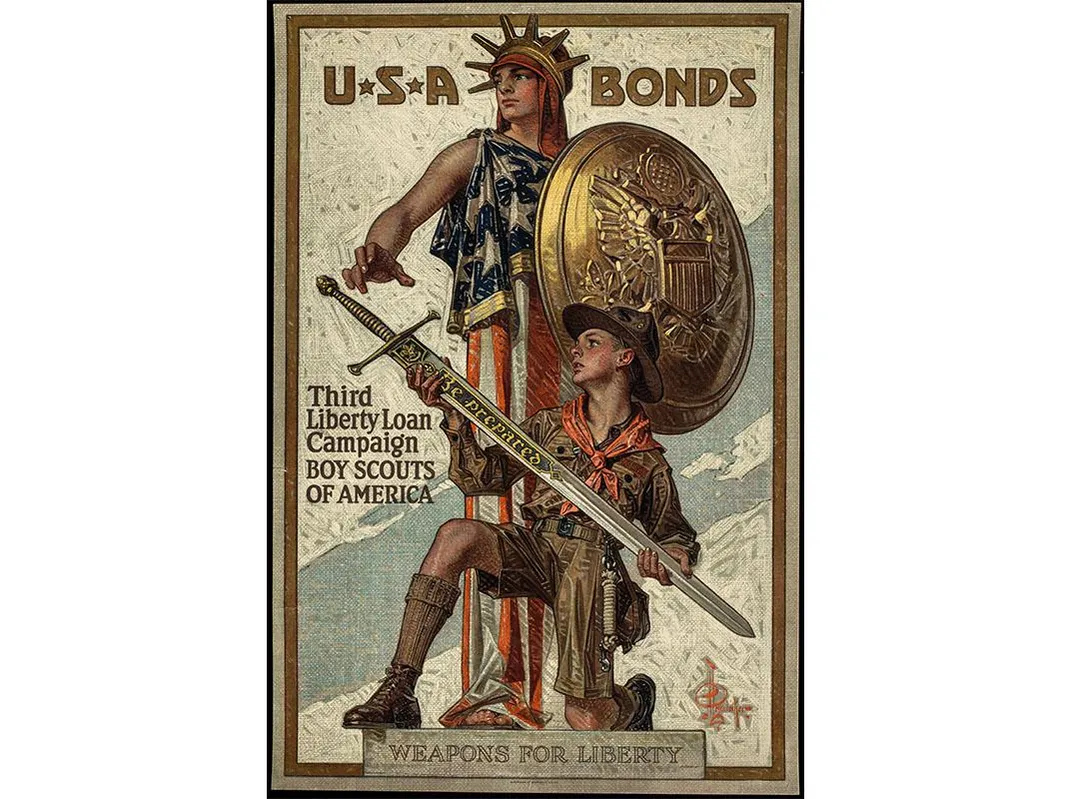

Other posters encouraged buying war bonds, rationing or aid to refugees and soldiers.

In all it was a “vast enterprise in salesmanship,” according to George Creel, who headed up the Committee on Public Information.

“We did not call it propaganda,” Creel said in his memoir, “for that word, in German hands, had come to be associated with deceit and corruption. Our effort was educational and informative throughout, for we had such confidence in our case as to feel that no other argument was needed than the simple, straightforward presentation of the facts.”

No doubt it was effective. In addition to the 3 million conscripted for service, 2 million men volunteered through the efforts, and $24 billion in war bonds were raised.

Not only did the poster blitz help solidify support for what had been an unpopular war, it also showed how powerful advertising could be overall.

“There was no radio or television at the time, so that was the only way to get people’s attention,” Miller says of the posters.

And 100 years later, the advertising continues simply in different media, he says.

“Sit back and watch a basketball game on TV and you’ll see two or three commercials to join the Army or the Navy or the Air Force,” Miller says. “They’re still advertising.”

“Advertising War: Selling Americans on World War I” is on view through January 2019 at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cd/6c/cd6cb071-158e-4363-8913-c8518703bffc/ahb2014q024669web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2e/54/2e54003e-b845-45ac-94a1-703725aea981/et201610439web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/77/5e/775e078f-8868-478b-b07b-369181e42284/et201610437web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)