The True Story of the Little Ballerina Who Influenced Degas’ “Little Dancer”

The artist’s famous sculpture is both on view and the subject of a new theatrical performance

:focal(546x45:547x46)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/b4/75b45b09-995d-4e08-a908-8ad798f110e2/degas-ballerinas.jpg)

Edgar Degas created a sensation when he presented his Little Dancer sculpture at the Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1881. His intention was to portray a young girl who dreamed of having an “illustrious life” in ballet, but who also kept “her identity as a girl from the streets of Paris.”

The public, accustomed to sculptures that showcased idealized women in marble, was outraged that Degas’s work depicted such a common subject—a young dancer drawn from everyday life and whose attitude reflected nothing goddess-like or heroic. Moreover, instead of chiseling her nobly in marble, he had rendered her in beeswax and found objects. In the face of rampant public disapproval, Degas removed the sculpture from display and stored it in a closet, where it resided in anonymity for the next four decades until financier Paul Mellon acquired the original wax sculpture in 1956 and gifted it to the National Gallery of Art in 1985.

Now, however, the sculpture has been reimagined into a musical theater spectacle, directed and choreographed by five-time Tony Award winner Susan Stroman; the all-singing, all-dancing production opened October 25 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. with aspirations of heading to Broadway in 2015. Stroman told me that the idea struck her when she was in Paris and saw Little Dancer, captured in bronze, at the Musee d’Orsay. The young girl is posed in a relaxed version of ballet’s fourth position, but there was something about her attitude—the thrust of her chin, the way she held her body—that made Stroman want to know more.

When she returned to New York, Stroman met with lyricist Lynn Ahrens and composer Stephen Flaherty. Ahrens and Flaherty are best-known for their legendary musical Ragtime, which won the Tony Award for Best Score in 1998. Stroman was eager to brainstorm with them about her “wow” idea, but she told me that before she could say a word, Ahrens burst out, “We should do a show based on Little Dancer!” Clearly, it was meant to be.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a2/ee/a2eea7f3-61a1-4a21-a3a8-a9cc81cbc56d/01-l-r-boyd-gaines-as-edgar-degas-and-tiler-peck-as-young-marie-photo-by-paul-kolnik.jpg)

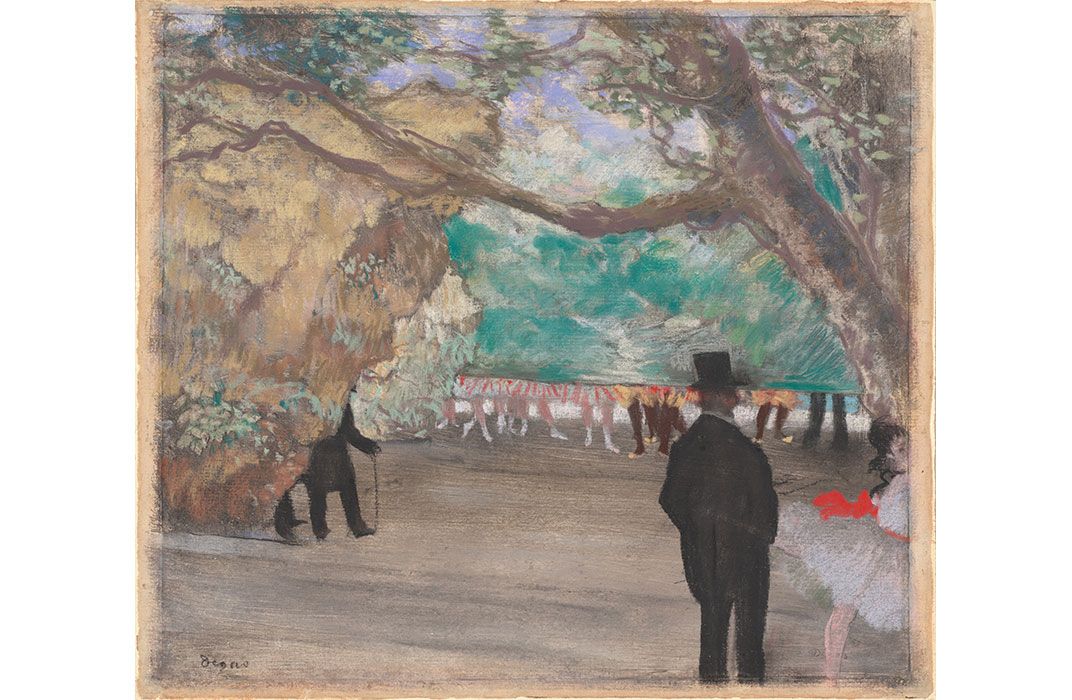

It turned out that Degas’ model was a street urchin, one of the “opera rats” who joined the Paris Opera Ballet as a way out of poverty. Her name was Marie Geneviève van Goethem and her mother worked as a laundress; her older sister was a prostitute, and her younger sister would also become a dancer at the Opera. Sculpted by Degas between 1878 and 1881, the work is often referred to as the most famous ballerina in the world. The artist was a frequent backstage presence, painting and sketching the dancers as they rehearsed or stood in the wings waiting to perform. He sculpted Marie when she was 11, rendering her in pigmented beeswax and nondrying modeling clay at age 14.

When Stroman, Ahrens, and Flaherty began to shape their new musical, they were immediately confronted by the fact that their real life subject’s story ended abruptly. Van Goethem, disappeared shortly after Degas’s sculpture was finished. She was dismissed from the Paris Opera Ballet in 1882 for being late to a rehearsal, and poof—c’est fini. Offsetting Marie’s untraceable later life, the new musical depicts a Van Goethem that is part fact, part fiction. To tell Marie’s story—“to bring her back to life,” as Stroman explained to me—the musical has invented an older Marie who narrates the story of her life as a young girl. Stroman “wanted to believe that she was different and had character,” that her life on the street had made her a fighter—an attitude that resonates in the way Degas’ Little Dancer holds her body in confidant repose.

Stroman says that she used many of Degas’s pastels and paintings of dancers to inspire her choreography, and that much of the dance in Little Dancer is actually classical ballet. In this dance-driven musical, she has also included a dream ballet—once a central part of such legendary shows as Oklahoma! For a 1998 London production of that musical, Stroman built on the original choreography by Agnes de Mille, who helped change American musical history by moving the story forward through dramatic dream dancing.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/29/f1292e22-bcd6-4a4a-a41d-331d6d04e044/04-l-r-boyd-gaines-susan-stroman-tiler-peck-photo-by-paul-kolnik.jpg)

Dwight Blocker Bowers, curator of entertainment at the National Museum of American History and co-curator with me on the 1996 Smithsonian exhibition, “Red, Hot & Blue: A Smithsonian Salute to the American Musical,” says that “a dream ballet is essentially a dance fantasy—part daydream of wish-fulfillment, part nightmare of deepest fears.” He noted that Agnes de Mille used these dances to strengthen the narrative with emotional impact and allowed audiences “to get inside (a character’s) mind.”

For Stroman, having a dream ballet in Act Two of Little Dancer seemed perfect. As she told the Washington Post's Sarah Kaufman: “I’m back to feeling ecstatic about having a ballet in a big Broadway musical.”

For those who cannot make it to the show, or even for those who can, the National Gallery of Art is displaying the original Degas wax sculpture (there are some 30 bronze versions held by various galleries worldwide.) The show also includes several pastels and oil paintings of Degas’ other dancers. The museum says that new technical studies reveal how Degas constructed a number of his wax sculptures up over brass and wire armatures and then building them up with anything he found at hand—wine bottle corks, paper, wood, discarded paint brushes, and even the lid of a salt shaker.

Little Dancer will continue to show at the Kennedy Center through November 30. Will Little Dancer fulfill its dream fantasy? The great thing about musical theater is that every night when the curtain goes up, a smash hit is always a possibility.

The Kennedy Center's production of Little Dancer can be seen in the Eisenhower Theater from October 25 through November 30, 2014. The exhibition Degas's Little Dancer is on view from through January 11, 2015 at the National Gallery of Art.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/85/f3/85f3982e-a2de-47af-9ccb-7fcd00c5907a/2-tiler-peck-in-kennedy-centers-little-dancer-photo-by-matthew-karas.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/d5/4fd55490-24c2-4120-a88c-74c2abe50d36/3971-003.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/6d/ec6dd399-f512-4f1b-a0d5-0072fae7db38/3971-004.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/29/13/2913444c-a195-4242-bbc0-b680aa6e1219/3971-005.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ce/fa/cefadfbf-8f45-4881-8758-5d9d4dce34dc/3971-006.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/86/d286ed15-0e37-4f12-b63b-c7eb8320d54d/3971-010.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6b/ff/6bff0741-d379-4174-a256-e0a7dff0a0a3/3971-013.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/72/5f/725f4928-e810-4bff-8a67-0431ccc2dbd6/3971-014.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fc/df/fcdf8efa-41b7-4f25-8db9-2d083075c769/3971-015.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)