Unearthing America’s Lawrence of Arabia, Wendell Phillips

Phillips uncovered millennia-old treasures beneath Arabian sand, got rich from oil and died relatively unknown

Wendell Phillips was in Marib, Yemen, searching for clues about the storied Queen of Sheba, when local tribesmen took him and his team captive. It was 1951, and Phillips hurriedly sent a cable to President Truman: “Unless your immediate action is taken, American lives will be gravely endangered.” Abandoning the project, he and his colleagues managed to escape with little more than the clothes on their backs. “Absolutely everything else was to be left in Marib,” he later wrote.

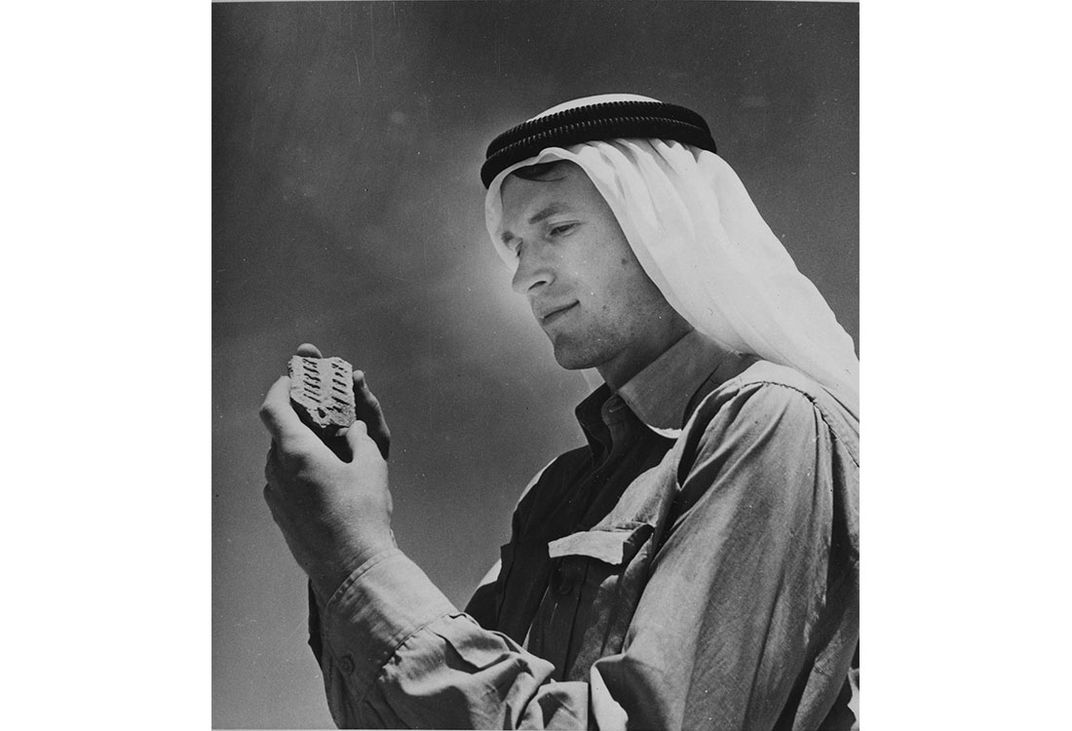

People have tried to make relatable comparisons to Phillips; some have gone with Lawrence of Arabia, others a real-life Indiana Jones. At age 26, armed with a degree in paleontology and experience in the Merchant Marines, he began his adventures in Africa. Then in 1949, at 28, he went to South Arabia. There, he uncovered artifacts from the city of Timna, once located along ancient trade routes. No western archaeologist had ever been there before.

Those Timna findings and the details of Phillips' legendary life are the focus of an exhibition at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, “Unearthing Arabia: The Archaeological Adventures of Wendell Phillips”, open through June 2015. More than 70 artifacts are on display and date as far back as the 8th century B.C.E.

A 1955 New York Times article said Phillips combined “the qualities of vision, courage, curiosity and enthusiasm with the cocksureness of a swashbuckling adventurer, the coolness of a gambler and the cunning of an American backwoodsman.”

“He and his team were incredibly influential in sort of laying the foundation of archaeology in this area,” says Massumeh Farhad, chief curator at the Sackler. “When you talk about archaeology in the Arabian Peninsula, inevitably it starts with Wendell Phillips.”

Zaydoon Zaid, an archaeologist who has worked with the Foundation for the Study of Man, which Phillips founded in 1949, remembers learning about him as a student. “He was the first foreigner to excavate in South Arabia,” Zaid says. “He opened the door for all archaeologists who came after him.”

Of the part of the world that would make him famous, Phillips wrote, “Time fell asleep here, and the husks of ancient civilizations were buried in deep sand, preserved like flowers between the leaves of a book. The land looked forbidding, but it was rich with the spoils of time, and I wanted to unearth some of those riches, digging down through sand and centuries to a glorious past.”

Thanks to the cameramen who accompanied Phillips in Yemen, the Sackler exhibition includes footage that Farhad says enables visitors to “get behind the scenes, so to speak, of the expedition, and really try to sort of understand how it was conducted, what it involved and what it was like.”

The footage depicts Phillips uncovering the same artifacts that appear at the Sackler. One object, an alabaster bust from a cemetery that dates to the middle of the first century, has become known as “Miriam.” “She’s monumentally worldwide famous,” says Merilyn Phillips Hodgson, Wendell Phillips’ sister and current president of his foundation, about “Miriam.”

Hodgson says she associates those artifacts with her youth. “I grew up with it. My brother used to bring it home,” she says. “‘Miriam’ sat in our living room. I thought, ‘Oh gosh, there’s no room for me.’” She recalls how her brother once warned her to watch out for the flirtatious locals in Egypt. “He had a great sense of humor,” she says of Phillips.

Following his hurried departure from Yemen in the 1950s, Phillips wrote a book about his adventures, titled Qataban and Sheba. “Herein lies the story of a dream, which like many dreams occasionally achieved nightmarish qualities,” the book begins. “I warn all others to whom romance, adventure, science, travel and the lure of the unknown beckon that the fulfillment of their dreams may also bring up on them the torture of split lips, swollen tongues, frozen fingers, dysentery, fever, heartbreak and monotony beyond compare.”

Following his mid-century expeditions, Phillips spent his time writing and teaching. He also used his Middle East connections to get into the oil business. According to the Biblical Archaeology Society and newspaper accounts from the time, by the mid-1970s he had more oil concessions than any individual holder in the world, valued then at more than $120 million. Yet despite his riches, he remained an enigmatic figure. He fell ill and died in 1975 at age 54.

Decades later, Phillips' work is no longer ancient history. Under his sister's leadership, his Foundation returned to Yemen in 1998 and picked up where he had left off half a century earlier. However, as it did 60 years ago, conflict has again halted archaeological efforts. “Unfortunately we can’t go to Yemen for the field work,” Zaid says. “I think at this time it’s very risky to take our team to go there.”

In light of those challenges, Zaid says, the Sackler exhibition can shed light on the Arabian history that predates contemporary conflicts in the region. “In this moment, when everything is going bad in Yemen,” Zaid says, “it’s very important to have an exhibit like this, to show the people that Yemen is something else.”

“Unearthing Arabia: The Archaeological Adventures of Wendell Phillips” is on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery until June 7, 2015.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/af/99afa570-89c7-4def-b2b7-2bd976a8ff47/untitled-4.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/56/3e/563eb3d7-15c2-4ed6-bdfb-99c20fc016cc/untitled-5.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6a/0e/6a0ee4dd-6602-42e1-910d-81ac63f21be6/untitled-2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07/9c/079cad8f-54ad-47ab-ac67-2b14cc24e4f2/untitled-8.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/82/6b/826b5748-1b9e-40e1-857e-e57b72ae676f/untitled-9.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/ef/69ef192a-c6a2-4104-b344-101bdbeb5b9d/untitled-13.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/96/18/96189de6-8daf-45f4-9036-ccc0574982e1/untitled-14.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/1b/4f1bdd60-fae9-4dc1-8163-0c955c5953c7/untitled-11.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/01/56/01560fe4-0d7f-4ff0-838e-6062e7ec4b5a/untitled-10.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20/ff/20ff7b7a-20ff-4296-a2a4-6ab400e9236c/untitled-12.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)