Watch How One Harlem Storefront Changes Over Nearly Four Decades

The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s new exhibition goes “Down These Mean Streets”

When it first caught the notice of Chilean-born photographer Camilo José Vergara in 1978, it was one of the last vestiges of old Harlem—the Purple Manor Jazz Club, with distinctive wavy window panes and painted accordingly.

But in the nearly four decades that he continued to photograph the storefront of 65 East 125th Street in Harlem, sometimes a couple times a year, Vergara saw it change into more than a dozen different incarnations—a microcosm of the neighborhood’s rapid changes.

As seen dramatically in more than 21 prints in the new show "Down These Mean Streets: Community and Place in Urban Photography" at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the establishment was split into two store fronts by 1980, only one of which still had the distinctive windows. The other had become a fish and chips shop.

Soon that was gone, replaced by a discount variety store in 1981, the wavy windows on the right were gone altogether. Before the end of that decade, the storefront on the left was an office, then a kitchen cabinet store while the right side became a 24-hour smoke shop that managed to hang on for nearly a decade.

During that time, the left hand side was a graffiti-scarred unisex boutique turned beauty stop, then a clothing shop that played up the current year (2001). Then the scaffolding went up and it was another generic urban mattress showroom. It didn’t last; it was transformed in the most recent images in the series on display into a storefront Universal Church.

“As we go through the photographs,” says E. Carmen Ramos, curator of Latino art at the museum, “we see the slow erosion of history, and the resourcefulness of residents and business owners as they deal with limited resources during the period of the urban crisis.”

The “urban crisis”—a time when manufacturing in U.S. cities collapsed, whites moved out, and poverty proliferated for those left behind since the 1960s—looms large in the exhibition of ten photographers, who each documented in their way the transformation of American cities in the last half of the 20th century.

Another series in the exhibit, Public Transit Areas, by Anthony Hernandez, notes the affect on the other side of the country in Long Beach, California, where those left out of the burgeoning car and freeway culture are seen in eight different 16 by 20-inch black and white prints, waiting seemingly forever at bus stops alongside wide, largely empty urban streets. What cars there are speed by in a blur.

“You start to see how many times the people waiting for the bus tend to be older people, or African Americans or Latinos,” says Ramos. “One thing you never see in this series is buses.”

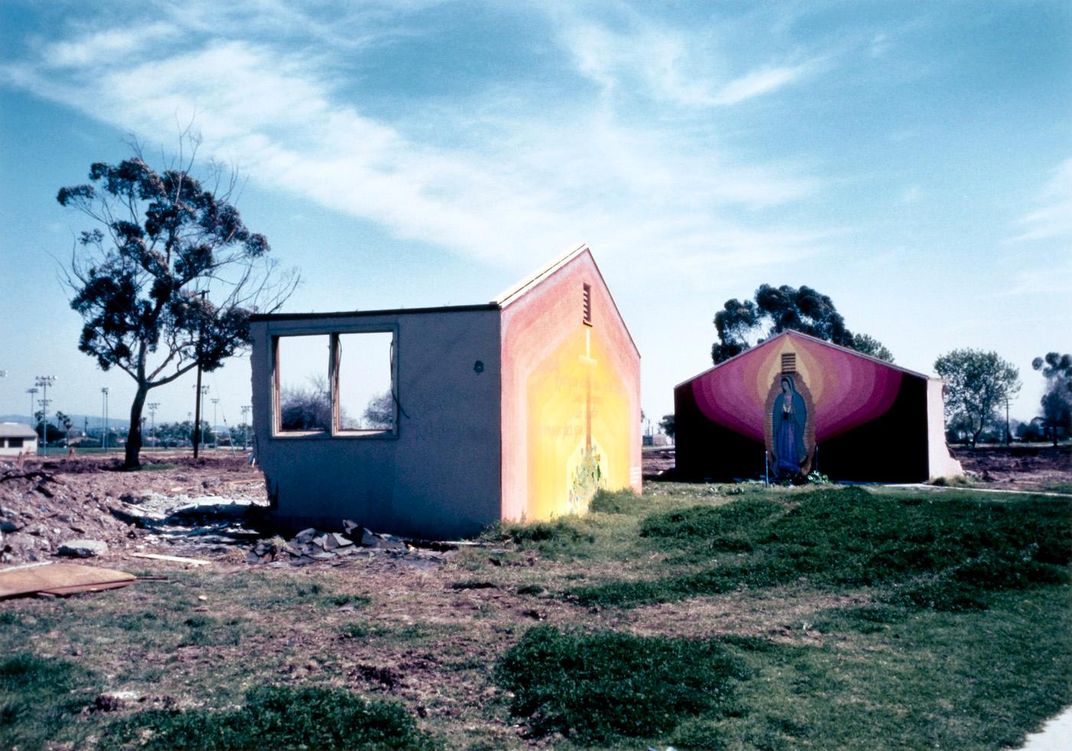

While some see bleak urban landscapes, though, some of the artists imagined what they could be.

Ruben Ochoa creates a large lenticular print that seems to shift as one walks toward it, eliminating part of the wall of Interstate 10 that winds through East Los Angeles and revealing some of the lush greenery it eliminated.

Similar possibilities for forgotten urban sites are offered by the Newark, New Jersey-born artist Manuel Acevedo, who sketches the bones of possible structures arising from otherwise empty lots.

“What I wanted to do was create these mock proposals for these interventions,” Acevedo says. He draws them on his original print, photographs them again and blows them up to somewhat heroic size as the 40 by 60-inch print of a forbidding corner in Newark.

Two of his drawn proposals for an empty lot in Harford suggest a building or stadium; another looks more like a fence separating the gleaming downtown spires from its less fortunate expanses.

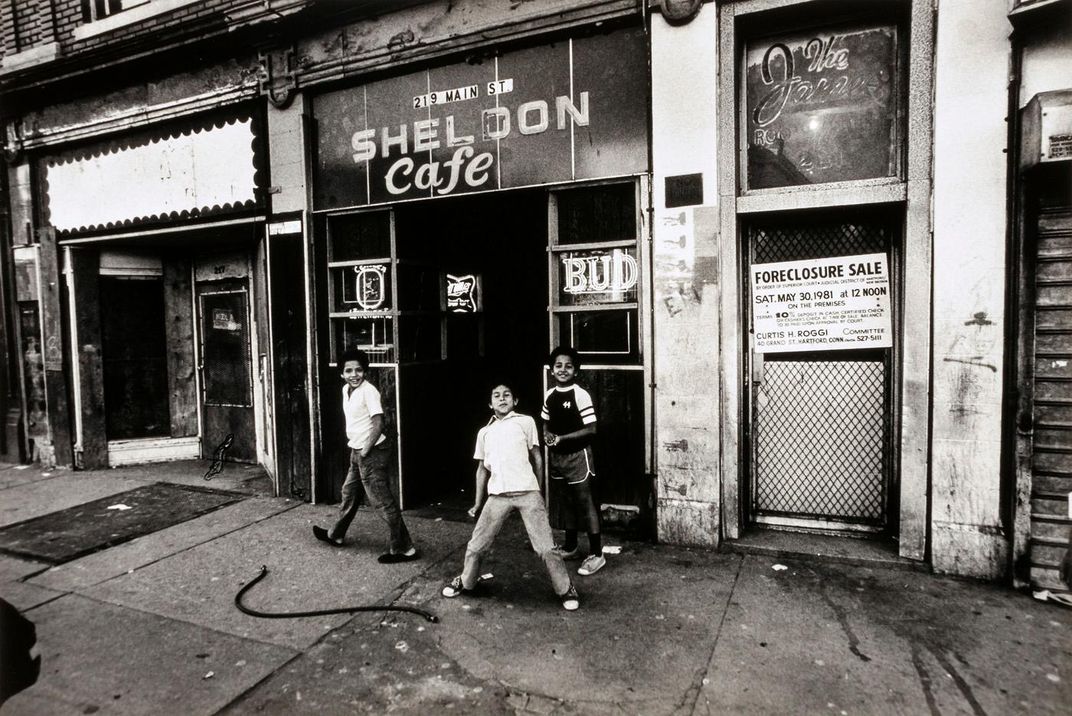

Some would expect to see the bleak urban landscapes of the South Bronx in such a show, and a few are there, but works from Oscar R. Castillo show some vibrant community organizations serving the neighborhoods, as does the works by Perla de Leon. In her pieces and in many of those of photographers who concentrate on portraiture of residents, it’s the gleefulness and joy of children making their own playscape out of their surroundings using only their imagination.

As the title, drawn from Piri Thomas’ 1967 memoir Down These Mean Streets, indicates, some of this pavement can be tough. But to children, they’re everyday playgrounds of their own making. Of course they play in front of the summer spray of hydrants of Hiram Maristany’s shots, but their streets are pocked with hopscotch chalk, not gang symbols. Winston Vargas brings out the bold personalities of young people in New York’s Washington Heights—as well as a wedding celebration. Frank Espada, in some of the earliest prints from the show, 1963, gets kids to smile wide.

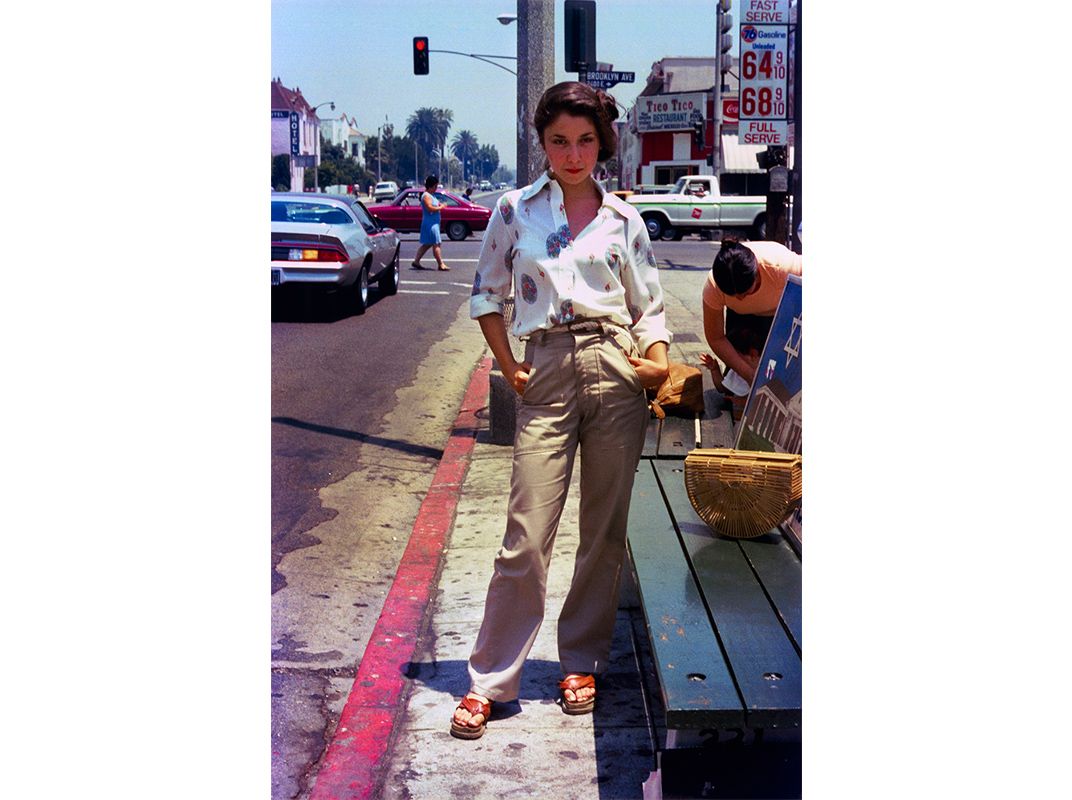

The painter John M. Valadez brings out the pride, swagger and fashion sense in his 1970s series East Los Angeles Urban Portrait Portfolio, which also stand out because they are in color rather than black and white.

“The Smithsonian American Art Museum has one of the largest collections of Latino art in a major art museum,” Ramos says. And nearly all of the 97 works in the show are taken from its collection, purchased through the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Pool administered by the Smithsonian Latino Center.

The museum also continues to acquire Latino art, and will add to its collections, for example, any future additions to the Vergara’s 65 East 125th Street series, chronicling future changes to that storefront for as long as the photographer keeps an eye on it. The museum already has 26 images from the series—the exhibition could only fit 21.

For artists like Acevedo, the revelation in the exhibition came in seeing how many other photographers were out there at the same time, chronicling their communities—unaware that others were also doing so.

“Having all of these elements, they speak to each other,” Acevedo says of the different approaches on display. “I didn’t know any of these photographers at the time when they were working. The artists in the 1970s were all working similarly in different barrios—there weren’t any real references.

“This is the first time you can come to a show, I feel, and you can really conceptualize it. You can talk about those numerous decades, and the ties and interests.”

"Down These Mean Streets: Community and Place in Urban Photography" continues through August 6 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f4/8f/f48f854f-5383-4179-9164-671b630de518/vargas_child_playing-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e7/0f/e70f2923-96e8-4088-96ee-be1a4acb2dd6/valadez_couple_balam-wr.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)