What Artist Martha McDonald Might Teach Us About a Nation Divided

This fall, a one-woman show staged in one of Washington, D.C.’s most historic buildings will recall the sorrow of the Civil War

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/79/6d/796d53eb-1b1a-430e-a065-e674a78791aa/17rc2014075272web.jpg)

Connecting the present to the past is the central mission of historians, and especially historians who work in museums. A new exhibition, “Dark Fields of the Republic,” which I curated for the National Portrait Gallery, looks at the photography of Alexander Gardner, a student of Mathew Brady, who was among the first to document the horrors of the Civil War battlefields. During the heroic and tragic middle period of the American 19th century, it was Gardner's shocking images of the dead that helped usher in the modern world.

Martha McDonald, a Philadelphia-based performance artist had been drawn to the question of Victorian mourning rituals in her earlier works The Lost Garden (2014) and The Weeping Dress (2012) and when we asked her to create a piece to accompany and amplify the themes of the Gardner show, she readily agreed.

Gardner was one of the major figures of the photographic revolution in art and culture that occurred in the United States and Europe in the middle of the 19th century. Scots-born and of a working class background, Gardner was fascinated by the emerging technology of photography and found employment in Brady's studio for whom he did both portrait photography and, most crucially, began to take pictures of the battlescapes of the Civil War. The success of his photographs in his 1862 exhibition, "The Dead at Antietam" allowed Gardner to strike out on his own, to set up his own gallery in Washington, and to continue taking pictures of the War and later of the American west.

To suggest the full dimensions of that past experience, artistic and cultural programs in poetry, dance and performance art will support the exhibition. McDonald, who was in the process of creating her work Hospital Hymn: Elegy for Lost Solders, sat down with me to discuss her artistic intentions and purposes, as well as her career as a performance artist. The piece will debut October 17 at the museum.

David Ward: The Portrait Gallery’s building was used as a troop depot, as a hospital and Walt Whitman worked as a nurse in the building. How much did the history of the building play into how you conceived your work?

On my first site visit, I was immediately struck by the idea that this gorgeous, stately building was once filled with the sick and the dying. I started thinking about all the spirits that were still present in the building and I thought, this is really rich territory to mine. I went home from that visit and read Whitman’s Specimen Days, which is in large part about his time as a nurse during the Civil War. Whitman writes specifically about visiting soldiers in the Patent Office hospital and how strange it was to see all the beds lined up next to the cases of patent models, especially at night when they were lit up. I was struck by how Whitman was obsessed with and heartbroken about the “unknown soldier”—the thousands of Union and Confederate soldiers who died far from home, with no family or friends around, and how so many of them were buried in mass, unmarked graves, or not buried at all, just left to decay in the woods or on the battlefield.

The second thing that struck me was Whitman’s fascination with how nature served as a kind of witness to the suffering and loss of the war. He imagines a soldier wounded in battle crawling into the woods to die, his body missed by the burial squads that came by several weeks later during a truce. Whitman writes that the soldier “crumbles into mother earth, unburied and unknown.” Now I know from reading Drew Gilpin Faust’s Republic of Suffering that this was not just an imagined incident, but one that happened to thousands of soldiers in the war. Both Specimen Days and Whitman’s later Civil War poems suggest that the bodies of these unknown soldiers became the compost of the nation—their spirits now present in every blade of grass, every sheave of wheat and every flower. He writes: “…the infinite dead—the land entire saturated, perfumed with their impalpable ashes’ exhalation in Nature’s chemistry distill’d, and shall be so forever, in every future grain of wheat and ear of corn, and every flower that grows and every breath we draw…”

DW: Gardner’s portfolio, "The Dead at Antietam" caused a sensation when it was exhibited in New York City in October 1862. The New York Times commented that the photographs had a “terrible distinctness” that brought the reality of war home to civilians. Would you talk a bit about how the themes of the exhibition played into how you conceptualized the piece?

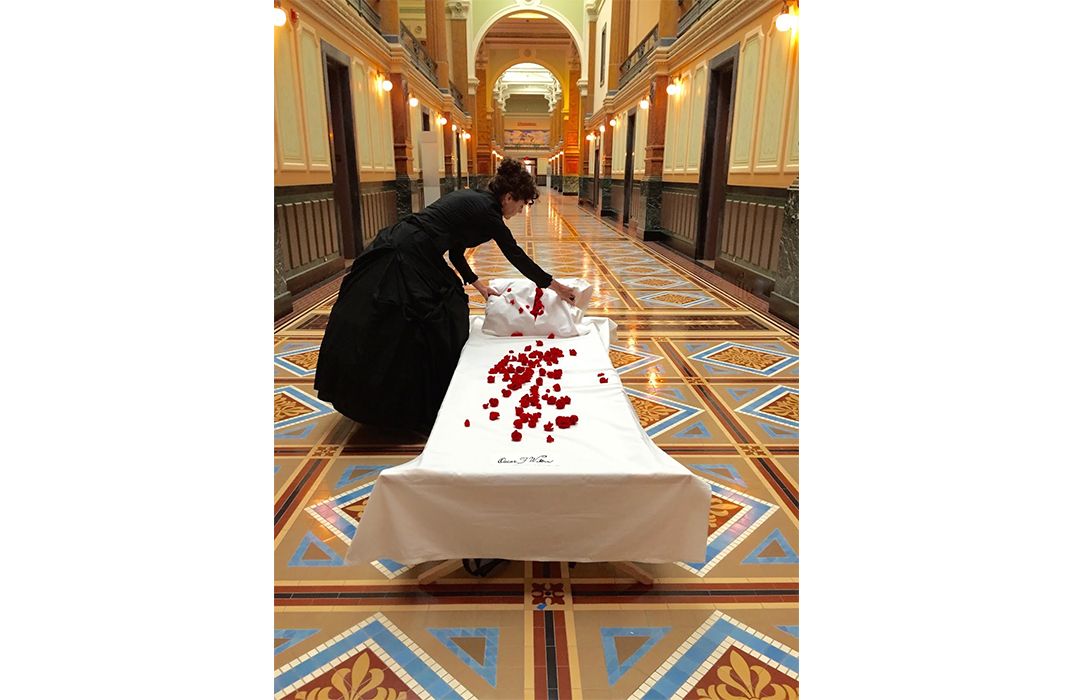

I was thinking about how I might express that idea in a performance in the Great Hall and I had this vision of filling up the entire hall with red felt flowers—the kind of flowers that a grieving widow, mother or sister might have made in her 19th century drawing room out of silk or paper or wax to commemorate her lost loved one. I envisioned it as a piling up of the work of all this grief, the grief of a nation of mourners.

Then I had the idea to suggest the temporary hospital by lining the hall with military cots covered in white sheets and that I would put the red flowers in pillow cases and release the flowers in the performance by cutting each pillow open to suggest the wounds tended in the Patent Office hospital and the blood that was shed. I wanted to suggest both the loss of life but also the work of mourning that was done by all those left behind, who struggled to mourn their loved ones without a body to bury.

This is a similar problem that mourners faced after 9/11. This question of how do you grieve without a body is important to me. So the thousands of flowers I’ll be releasing suggest the enormity of the loss but they are also symbols of renewal and rebirth, as suggested in Whitman’s compost imagery of flowers springing from the dark fields of battle.

DW: We were drawn to you because of your work personifying mourning. And we’ve had conversations about the title of the exhibition “Dark Fields,” which suggests the weight and tragic aspects of a crucial period in American history.

There is an Alexander Gardner photograph in the exhibition that shows the bodies of dead soldiers lined up on the battlefield before they are to be buried. When I first saw the photograph, I was overwhelmed by the sheer number of dead, but I also found it oddly beautiful the way their bodies formed a long arc across the field. It is almost sculptural.

When I look at the copy of the photo I have hanging on the wall in my studio and then I look at the pile of red flowers on the cot I have set up in there, it feels like my red flowers can also be seen as stand-ins for the lost soldiers, the sheer volume of flowers hinting at the immensity of human loss. The Gardner photos will inform the audience’s viewing of my more lyrical approach to the subject matter.

I will also be making a small booklet for the audience similar in size to the little notebooks that Whitman kept while visiting soldiers. The booklet will have some background information on the Patent Office’s use as a hospital and Whitman’s role there, as well as lyrics for the songs I am singing. So people will get a little bit of education from that as well.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/a7/c4a76fe7-9eb6-49b8-8d46-ca440e111561/martha2largeweb.jpg)

DW: I think we forget how noisy ordinary life was circa 1850-80—to say nothing about the volume of noise in a battle like Gettysburg—and similarly the smell and the odors of that period. People today don’t realize how unpleasant it was—horse shit all over the streets, tanning mills, unbathed bodies, clothes that were never cleaned. How much of that are you going to bring to you work?

Oh, the smells of the 19th century! I can only imagine the horror of it all! Reading Whitman’s Specimen Days and Faust’s Republic of Suffering certainly gave me a sense of the putrid odors that would have swirled around the Civil War camps, hospitals and battlefields but the cities were pretty fowl-smelling places as well.

I pondered that a lot when I was researching Victorian mourning dresses and how the unstable plant-based dyes stained women’s bodies. People bathed so seldom, the stains hung around for a long time, sometimes long after they moved out of mourning. The recipes I found in ladies magazines for removing the stains seemed horrible—the main thing they used was oxalic acid, which is what you use to clean silverware. I am not addressing 19th century smells in any way in this piece but I am interested in suggested other sensory experiences from the period—the sound of my feet echoing through the hall as I walk from cot to cot, the rough texture of the felt flowers against the crispness of the white sheets.

DW: We conceptualize the past through written documents or portraits—before the 20th century there were few recordings—we tend to think of the past as silent which I think plays into our romanticization of it—frozen in silence like an exhibition display behind glass. How will you address that?

I will be singing a number of old hymns that were popular during the Civil War era, some taken from the sacred harp tradition of the South and others that are Northern folk hymns, like “The Shining Shore.” I recently read that [the hymn] was very popular with soldiers during the war, but that it fell out of fashion because it reminded veterans too much of the war. Little wonder with its chorus: “For now we stand on Jordan’s strand/Our friends are passing over/And just before the Shining Shore/We did almost discover.”

DW: How do those hymns play into your performance?

The music I will be singing is based on Whitman’s recollection of walking into the Armory hospital late one night and hearing a group of nurses singing to the soldiers. He describes the songs as “declamatory hymns” and “quaint old songs” and lists some of the lyrics for “The Shining Shore,” which I am learning now. He describes the sight of “men lying up and down the hospital in their cots (some badly wounded—some never the rise thence) the cots themselves with their drapery of white curtains and the shadows” they cast. How they tilted their heads to listen.

He says that some of the men who were not as far gone sang along with the nurses. I was surprised when I read that passage about singing in the hospitals, but then I remembered all the accounts I had read of 19th-century families singing at home for recreation and singing around the bed of a sick or dying loved one and it reminded me how pervasive music (or “home-made music” as Whitman titled his entry about the singing nurses) was in the 19th century. People sang for every occasion.

And as I mentioned earlier, singing provided a way for people to express intense emotions—too intense for polite society—like grief and loss. I am a big believer in the healing power of a sad song. When a lament is sung, the singer invites the listeners to come in contact their own grief. The performance of a lament or sad hymn creates a space for people to cry or to live out their emotions in public in a way that is deeply healing because it allows listeners to live out their own personal dramas in a crowd of individuals who are each processing their own grief or experiencing other deep emotions.

DW: You’ve evolved a number of pieces that draw on American history, which as an American historian I have to commend. What draws you to the past?

My work engages in a dialogue between the past and the present. I find deep resonance with the handcrafts and folk songs people used in the 18th and 19th centuries to cope with and express feelings of loss and longing. I appropriate these historic art forms in my performances and installations as a way to articulate my own losses and longing and to explore presence and absence. I look to the past to reflect on the present but I am certainly not the only American artist looking to our history as a source for inspiration.

DW: I get the sense that contemporary artists aren’t all that interested in American history as a source or inspiration—am I wrong?

My work can be contextualized within a group of contemporary artists engaging with history and folklore to explore personal narrative and reflect on the current socio-political climate, artists like Dario Robleto, Allison Smith and Duke Riley. These artists appropriate folk crafts to convey their personal narrative, including 19th-century hair work and soldiers trench art (Robleto) sailor’s scrimshaw and tattoo art (Riley) and Civil War re-enactor’s costumes (Smith).

There were a couple of recent exhibitions of contemporary artists engaging with history, including “The Old Weird America: Folk Themes in Contemporary Art” at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (2008) and “Ahistoric Occasion: Artists Making History” at MASSMoca (2006) that show the breadth of this trend.

DW: You’re a committed feminist, could you talk about your recovery of women’s voices as an aspect of our evolving historical understanding.

I have always been interested in recovering women’s voices in my work—whether looking at female stereotypes in opera, literature and mythology as I did in my early work, or exploring the history of women as keepers of memory in my more recent work. Being a feminist is integral to my art practice.

My work is a kind of a performative response to women’s social history, in all its richness and complexity and invisibility. There is a really great book I recently read called Women and the Material Culture of Death that is all about recovering the largely invisible work that women did over the centuries to commemorate lost loved ones and keep the memory of families, communities and the country alive. Drew Gilpin Faust also addresses the key role women played in healing the nation after the Civil War in her book.

I am inspired as an artist by these craft forms, but I also think its important for people to know about them as material practices that helped society to address and live with death and loss. Contemporary society lacks these rituals. We deny death and aging. As a result, we are completely out of touch with our own impermanence, which causes all sorts of problems like greed, hate crimes, destroying the environment, etc.

I hope my work reminds people about impermanence and to think about their own lives and how they might adapt some of these rituals to face and live with the loss that is all around them.

DW: Talk a bit about your artistic evolution or trajectory and how you were originally trained.

I usually refer to myself as an interdisciplinary artist. I make installations and objects that I activate in performance to transmit narrative. For the last 10 years my work has focused a lot on site-specific interventions in historic house museums and gardens where I draw on the site and its stories to explore how these public places connect with private histories and emotional states.

My art practice developed through a pretty unconventional trajectory. I started out working as a journalist. I was a newspaper and magazine writer. I also sang with professional Baroque ensembles—performing in churches and concert halls. In the mid 1990s, I crossed paths with a queer, highly politicized performance art scene in Philadelphia, performing in cabarets and nightclubs.

As I sang my baroque arias in this milieu of drag queens and AIDS activists, I discovered the powerful potential of costumes to convey narrative. Nurtured by benevolent drag queens in this super theatrical environment, I developed performance pieces that drew on the artifice of Baroque opera and the mythological characters that peopled them to explore gender, identity and power and my own personal narratives.

I drew on my journalism background to do the heavy research and write monologues that I spoke to the audience. I made a piece about mermaids, sirens and harpies—half-women/half-beasts that don’t fit in on land, sea or air—and my relationship to them. I explored the Madwoman in Opera. I made another big piece looking at the mythological Penelope’s epic labor of weaving and unweaving to explore the pain of waiting and acceptance, drawing on my mother’s death. These shows often included video projections (I sang Henry Purcell’s siren duet with myself on video), elaborate sets and sometimes other singers and dancers.

DW: As a person interested in creating art, how have you evolved into a performance artist.

After years of showing work in theaters, I started to feel really limited by the flatness of the theatrical proscenium and the distance of the audience sitting passively in the darkened theater. Around that time I got invited by the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia to make a piece in response to their collection of rare books and decorative arts.

I was fascinated by how the Rosenbach brothers used their collections to reinvent themselves: They grew up as sons of middle-class Jewish merchants who went bankrupt but as the brothers’ amassed a fortune from selling rare books in the 1920s, they assumed the lavish lifestyle of English country gentlemen. My performance took the audience on a tour of the museum, focusing on objects that were pretending to be something else—chinoiserie mirrors, Empire furniture, forged Shakespeare folios—to examine how we use our objects to redefine ourselves.

Making the Rosenbach show made me realize that I was not so interested in creating “stage magic” to transport the audience to somewhere else anymore. What I really wanted to do was to literally take them through sites and uncover their hidden histories through a kind of song tour.

Since then I have led audiences through an 18th-century botanic garden, a Victorian cemetery (both in Philly), on a tiny boat traveling down a river through the center Melbourne, Australia, and out into the shipping lanes, and in a private in-home theater designed by Leon Bakst in the 1920s in the basement of a mansion in Baltimore. Throughout all of these pieces, my main interest was to awaken the audience to the experience of being in the site—the smell and taste of herbs in the kitchen garden, the wind in the trees and the swallows feeding on insects in the cemetery, the giant container ships that dwarfed our little boat on the river and the angle of the setting sun at twilight. I began to speak less and less in my performances and let the site and my objects speak more.

Singing has always been central to my art practice. It is probably the most essential mode of expression for me. I feel like it allows me to communicate with an audience much more deeply than speaking can. It allows a different kind of emotional contact. As an audience member, I get such a rush of emotion when I feel the vibration of a singer’s voice—especially up close—in my own body. I know how powerful that can be. Singing also allows me to explore and activate the acoustics of these spaces and to evoke the memories of the people who once lived and worked there. Its almost like I’m conjuring their spirits through song.

When I moved to Australia in 2008, I had the incredible opportunity and freedom to experiment with my work, to try new things and to jettison others. I stopped singing Baroque music at that point because I wanted to spend more time making the objects and costumes and less time keeping my voice in shape. You have to be like a professional athlete to sing that music—vocalizing several hours a day 5- to 6-days a week. When I began making work in Australia about Victorian mourning culture, I reconnected with Appalachian folk music and I continue to find its haunting melodies and lyrics so well-suited to express yearning and loss. I am also really interested in how Anglo-Irish immigrants brought these songs to America as keepsakes of the homes they left behind. I am fascinated by how people use folksongs to bind themselves to people and places they have lost and to express feelings they are not able or not permitted to express in polite society.

I am interested in taking the audience on a physical journey through time and space, often by literally walking them through a site. But I also want to take them on an emotional journey via the music and visual images I create—to encourage them to think about their own lives and their own losses.

DW: As a final question, what do you hope to achieve in creating and performing this piece?

I guess I hope to achieve several things with the performance: I would like to create an experience for the audience that awakens them to the site of the Great Hall—to the amazing acoustics, the grand architecture, and the “hidden” history of its use as a temporary hospital during the Civil War soldiers where soldiers died.

I would like the audience to think about the volume of loss during the Civil War 150 years ago and perhaps how that relates to the current losses we experience in the ongoing conflicts in the Gulf region and in the escalating racial violence, taking place across the country right now.

And finally, I would like to invite the audience to think about their own lives and their own losses and to have the opportunity to share in a collective moment of grief and renewal. This is probably a lot to ask of an audience, but this is what I am working towards as I develop the project.

On September 18, 2015 the National Portrait Gallery will open the exhibition “Dark Fields of the Republic. Alexander Gardner Photographs, 1859-72.” Martha McDonald will debut her work as part of a performance art series, “Identify” that will be inaugurated this year at the National Portrait Gallery on October 17, 2015 at 1 p.m.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/David_Ward_NPG1605.jpg)