What Digitization Will Do for the Future of Museums

The Secretary discusses his new e-book about how the Smithsonian will digitize its collections and crowdsource its research

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130829093031book-copy1.jpg)

![]() In a first of its kind, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution G. Wayne Clough has published a new e-book, entitled Best of Both Worlds: Museums, Libraries, and Archives in a Digital Age. As a call to action, Clough charts the course that the Smithsonian will follow in the coming years in digitizing its artifacts, crowdsourcing its research and opening up its collections for public interpretation and consumption. “Today digital technology is pervasive, ” he writes, “its use, particularly by the world’s youth, is universal; its possibilities are vast; and everyone in our educational and cultural institutions is trying to figure out what to do with it all. It is mandatory that museums, libraries, and archives join with educational institutions in embracing it.”

In a first of its kind, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution G. Wayne Clough has published a new e-book, entitled Best of Both Worlds: Museums, Libraries, and Archives in a Digital Age. As a call to action, Clough charts the course that the Smithsonian will follow in the coming years in digitizing its artifacts, crowdsourcing its research and opening up its collections for public interpretation and consumption. “Today digital technology is pervasive, ” he writes, “its use, particularly by the world’s youth, is universal; its possibilities are vast; and everyone in our educational and cultural institutions is trying to figure out what to do with it all. It is mandatory that museums, libraries, and archives join with educational institutions in embracing it.”

We sat down with Secretary Clough to learn about his motivation for writing the book, the difficulties in digitizing 14 million objects and his favorite digitization projects so far.

What first got you interested in digitization and thinking about the Smithsonian’s involvement with it?

I’ve been involved with computing all my professional life. I tell people that when I went to Georgia Tech as an undergraduate, the first course I had was how to use a slide rule, and the last one was how to use a computer. I put the slide rule away, and became very involved with computing. My thesis, at Berkeley, in the 60s, used a CDC 6600 machine to simulate complex environments. This kind of technology revolutionized the way we could think about geology and engineering.

Later, in my life as a faculty member and an educator, I used computing throughout. At Duke, the first assignment they gave me was teaching a freshman course in computing, and I really had a ball doing it, so it’s been something I’ve been at for a long time. As an administrator, I always had people trying to sell me different technological tools that would revolutionize education. All the same, it wasn’t quite time yet. The tools weren’t robust enough, they were too balky, they couldn’t be scaled.

When I came to the Smithsonian, it was clear to me that there was a huge potential and that we were finally at a tipping point in terms of the tools that we could use. What was happening was that everyone had their own devices, and then apps came along, and offered huge possibilities. Social media came along. And now it’s changing so fast. Just a few years ago, we didn’t have social media, and now Smithsonian has 3.5 million people following us on social media.

In those early years, what we did was experiment. I said ‘let a thousand flowers bloom.’ So we put up a venture fund called the Smithsonian 2.0 fund. Then through the Gates Foundation, we established a $30 million endowment for reaching new audiences, so we let people compete for those funds. All of a sudden, people were coming up with great ideas, so we could see things happening, but we didn’t have an umbrella over it.

So that is the next step, and the book really is the thought process of how you put this together and make it work—keeping the innovative and creative spirit within it, not saying everything has to be the same, but at the same time lift all parts of the Smithsonian up in digitization. It’s not going to be workable for us to have two museums at the top of their fields in this area, and 16 not. So how do we move everybody up into the game? The opportunities are there for us to reach people everywhere, and to me, the timing is just perfect to implement these ideas.

What, in a nutshell, is your vision for the digital future of the Smithsonian? In 10, 20, or 30 years, what are going to be some of the key ways the Institution embraces digitization and uses it to give access to the public?

Looking down the road, we will see people engaged in the creative activities of the Institution. In the past, the creative activities were entirely behind the walls of museums and collection centers. The public only got to access that through labels in exhibitions, which told them what we thought. Now, in this new world, people actually will help us design exhibitions, and it will be interactive. We have a beta version of a volunteer site, for example, that has several hundred working with us on projects. Essentially, you put up tasks, and volunteers can choose which ones they want to do. They submit their credentials, then, say, transcribe a cursive journal. Fundamentally, they’re taking things that have never been seen before by the public and making them available.

There are also cases where people know more about certain artifacts than we do. We have lots of implements from Native American tribes, and they may know more about them than we do, and we’d love for them to tell us about those objects. People are going to be engaged with us in a conversation, not a monologue. We’re not the ‘Voice of God’ anymore.

It’ll also mean letting people share in our research. We have this thing called LeafSnap, an app that identifies tree species based on images of their leaves. And if you take a picture and tell us you did it, we know where you were, and we know what that tree is. So we’re now mapping tree ranges based on people’s reports of that information. In the future, that’ll be extremely valuable, because as global warming hits, ranges of trees will change. Up at the Harvard-Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, we have the Colorful Cosmos project, where kids in a hundred museums are able to use their telescopes, and those kids are able to talk to Smithsonian scientists. That never would have happened before.

The other thing is that fundamentally, this is going to change the way our Institution works. We’re going to have to be a much more flexible and adaptable Institution, because maybe the greatest technology today may not be in the future. If we don’t shift and move, we’ll get left behind.

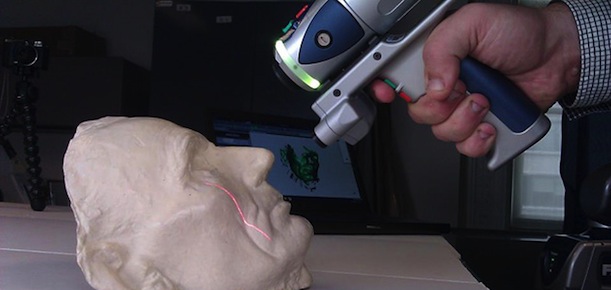

Smithsonian staff perform a 3D scan of Abraham Lincoln’s death mask. Image via Smithsonian Digitization Program Office 3D Lab

In the book, you also wrote that you want Smithsonian to digitize 14 million objects as a start. How do you prioritize which objects to make digitally available first?

It’s a good question, because even 14 million is too big. It’s better than 137 million, but it’s a huge number. When you think about digitizing a three-dimensional object, somebody has to go get it, they need to bring it somewhere where there’s sophisticated scanners, they need to scan it, and then they need to process it and then put it back. Think about doing that 14 million times. They estimate that would take 50 years, at best.

So that’s why you have to prioritize. There are a few elements in that. One is that we kind of have an understanding of what we think people would want, and we’re also asking people what they would want. So our art collections, for example, contain around 400,000 art objects. So we’ve asked our art people, and they told us 20,000 objects that are the best of the best. So we’re going to do high-resolution digitization of those objects.

Once you’ve identified these, there are robots that can produce the images. So they can do it relatively quickly. It’s a little gizmo, and it goes up to a painting on the wall, scans the thing, and then it’s finished. Then you put another painting on the wall, and it does that one.

Of the digitization projects the Smithsonian has done thus far, which are some of your favorites?

Well they’ve been at it for a few years now, and I’ve been fascinated by it. One of the first things they did was the Kennicott skull, which I keep on my desk and scare people with sometimes. I’ve also got a few other ones in my office—Lincoln’s death mask, and Owney, the postal dog. I’ve also got a 3D print of an instrument that will go up on a solar probe to measure the solar wind—it’ll go up in 2018, and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory folks decided the best way to visualize it was to print it in plastic, so I’ve got that.

There’s also another story I really like. I went to a meeting with some of our people in the repatriation business—when a Native American tribe says, ‘we want this object back, and we can prove our ownership of it.’ Many of these objects are funerary items, so when the tribes get them back, they’ll bury them, and they’re gone from view. So our people have been saying to the tribes, ‘we’d love to make a three-dimensional copy of it,’ and with their permission, they’ve been making copies. They can paint the things, and they look exactly the same as the original objects. So in some cases, the tribes have seen the replicas, and said ‘wow, can you make some for us?’ Because they don’t want people handling the real deal, but want to have access to it. In some cases they’re even sending us their own objects, asking us to make copies.

To me, that’s where it’s all going. I just think it’s going to get cheaper, faster, quicker. It’ll take a while, but it makes things so accessible. You put the image or file on your iPad and can see the items, play with them. It really brings history alive.

With the book, you’re putting a statement out there that this sort of digitization is a priority for the Smithsonian. Why is it important that the Institution leads in this field?

When I came, people used to say ‘We’re the largest museum and science organization in the world.’ I’d say, ‘So what? We want to be the best.’

And if you want to be the best, that’s a big word. We’re one of the best in putting on exhibitions. We have the best collection of stamps, one of the best scientific collections. But you can’t be the best at your business if you walk away from anything this big. So if the Smithsonian wants to be a leader in museums, or astronomy, or whatever, it has to be a leader in the digital world.

The other thing is that this gives us a chance to deliver education to every person. And we can tailor the stories we tell based on the audience, and setting. And so suddenly, that “Voice of God” is no longer there. We can be much more considerate and thoughtful about what we provide. It’s very clear to me that we’re moving into a world where people want to customize the way they approach things. We provide teachers with lesson plans, for example, but they tell us that they just want to use them as a basic framework to put their own lessons in. We have a lesson plan on science in your backyard, but if you live in Tucson, it’d be a different story than the one you’d tell in Bellingham, Washington, where there’s tons of rain. So teachers want a framework, but they want to put their own substance in. So more and more, I think we’re going to be a facilitator.

The other thing is, once you start putting everything in the cloud, it all becomes a mixed bag. What’s the difference between the art of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian when it’s in the cloud? People are going to be less concerned with where things come from. When they go to a museum, they’ve got to go to the Met or the Smithsonian. But when it’s in the cloud, they don’t really care. When they’re looking at a Winslow Homer painting in the cloud, they don’t care if it came from the Met or the Smithsonian—they’re just looking at a painting. So that’s going to change the way we do business and approach things. And I think, again, it’s a reason that it’s important for the Smithsonian to be a leader, so we can be controlling the options—at least understanding and appreciating and shaping the options—but if you’re not a leader, they’re going to shape you. People are looking to us to be a leader in this field.

When you put data about these artifacts in the cloud, how do you guard against technology becoming obsolete and losing access to this data?

We have a group working on this—they call it time-dependent materials. We have lots of objects in our collections that are subject to deterioration over time. The old film movies are a classic example of that, but there are lots of examples. Can you still read 8-track tapes? So we’ve got a group studying this, trying to figure out how to deal with it and ensure you have access in the future.

A good example of overcoming that sort of barrier, right now, is we have thousands of field journals that people made notes and illustrated with on hugely important expeditions. We have some of Charles Darwin’s notebooks. So in a way, that’s an obsolete medium, because few people can read it. But if you can digitize it, everyone can read it. So we have a volunteer transcription center to help transcribe cursive into a digital format.

You chose to publish these ideas in an e-book format. What do you think about the future of books and reading? Do you read on paper or e-books?

Well, when I got to the beach, I still like to have a real book. An iPad doesn’t work well out in the sun. But I’ve tried everything—iPads, Kindles, etc. Right now, it’s all about convenience, which is why I mostly use the iPad. If I’m sitting at the airport and realize I wanted to download a book, I can just download it right there. But I still like a real newspaper. The digital version doesn’t do as much for me. A real newspaper, you can flip back and forth, go back to earlier articles. But one thing I like about the iPad, I can go back and see what I read a few years ago. Sometimes I even go back and read the stuff I’ve finished over again years later.

Best of Both Worlds: Museums, Libraries, and Archives in a Digital Age is available via a free PDF.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)