What Does a Beer Historian Do?

The American History museum’s latest job opening made headlines. But what does the job actually entail?

:focal(573x517:574x518)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f4/24/f424d633-8cbc-4aa2-9fdb-32588b98756b/istock_65638789_medium.jpg)

When August Schell left Germany in 1848 and headed to the United States, he eventually made his way to New Ulm, Minnesota, where he opened his own brewery in 1860. He made the beer he had growing up in the Black Forest region of Germany. Like many immigrants of the mid-19th century, he longed for a taste of home, so he made one and shared it with his community. Through economic ups and downs, Schell’s Brewery has been operating in New Ulm, Minnesota, ever since. His is a story of immigration and community, and it’s also a story of beer.

When the Miller Brewing Company produced buttons made of plastic and metal that featured a woman standing on a box of beer and brandishing a whip, it was using the technology of celluloid plastic to create branding that would sell more of its product. Theirs was a story of American advertising, and it’s also a story of beer.

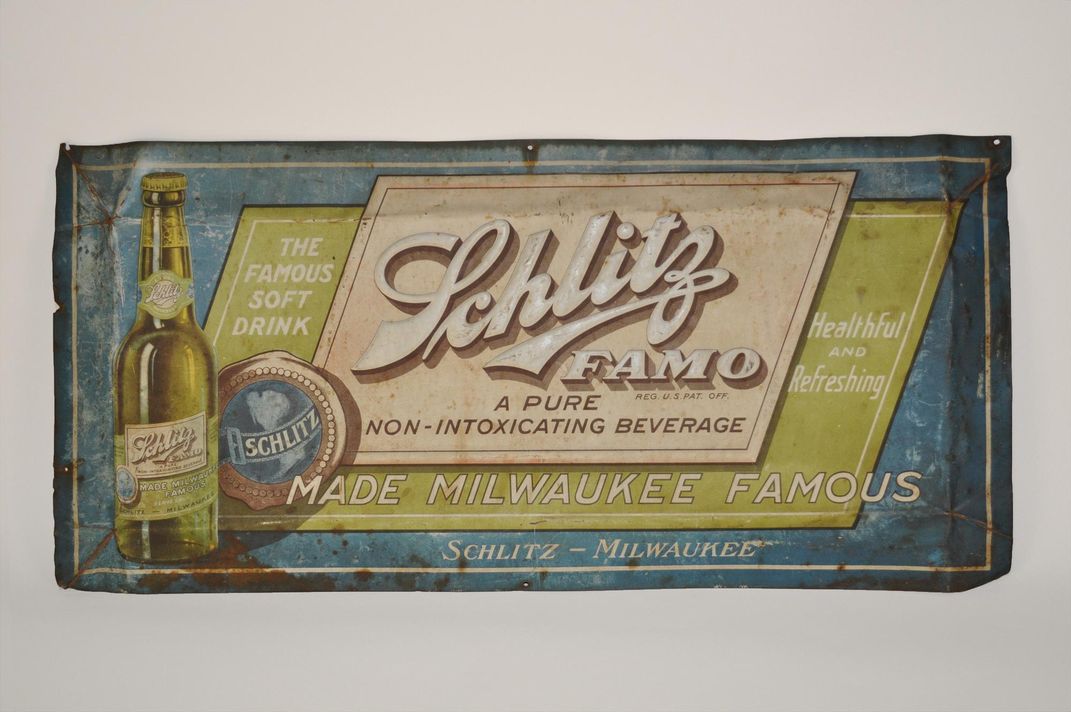

When Prohibition stopped the commercial sale and production of alcohol, the Joseph Schlitz Beverage Company of Milwaukee began producing FAMO, “a pure non-intoxicating beverage” that was both healthful and refreshing, a claim that addressed the Temperance Movement’s concerns about the ill-effects of alcohol. This was a story of economic and business innovation, and it’s also a story of beer.

And when President Jimmy Carter signed HR1337 in 1977, he reversed the Prohibition-era ban on making beer at home, leading to a boom in home brewing that inspired the first generation of the current wave of craft brewery owners in the United States. His was a story of American political history, but of course, it’s also a story of beer.

Beer history is American history and a new historian joining the Smithsonian Food History team at the National Museum of American History will help the public make sense of the complex history of brewing. As part of the American Brewing History Initiative, a new project at the museum supported by the Brewers Association, the historian will explore how beer and brewing history connect to larger themes in American history, from agriculture to business, from culture to economics. Today, there are over 4,200 breweries in the United States, the most at any time since Prohibition. As American brewing continues to expand and change, and our understanding of beer in American history deepens, the Smithsonian is uniquely positioned to document the stories of American brewers and collect the material culture of the industry and brewing communities for the benefit of scholars, researchers and the public.

But what exactly does a brewing historian do?

Research brewing history: The brewing historian will research, document and share the long history of brewing in America, with special attention to the post-1960s era. So for all of the history majors whose parents questioned their choices, feel free to relish this moment.

This means she or he will build on existing brewing history collections at the museum through research, collecting, and oral history interviews, all skills developed through years of graduate-school-level research. The Museum has several collections of objects and documents related to brewing, advertising and beer consumption in America. The bulk of these collections dates from the 1870s to 1960s and includes brewing instruments and tools, tap handles, advertisements, and much more.

Document the people that keep America’s taps flowing: She or he will document the stories of brewers, entrepreneurs, business and community leaders, hops farmers, and others who have influenced or been influenced by brewing in the United States. Reflecting our national scope, we will be looking at brewing across the United States and over time, from the changing homebrew laws of the 1970s to the craft beer expansion of the 2000s and beyond.

Share this new research with the public: The Brewing History Initiative is committed to doing our work in front of the public and the brewing historian’s role at the museum will include writing about his or her findings for public consumption, including the American History museum’s blog and in other media. The historian will also speak at public events in Washington, D.C., and around the country. The first event will take place at the Smithsonian Food History Weekend this fall.

Increase and diffuse knowledge, not just drink it in: While we love experiencing history firsthand, this position is not about drinking on the job. The historian will, of course, taste some beer, but his or her real focus will be on documenting American history for future researchers, scholars, and the public. In the words of Smithsonian benefactor James Smithson, this project, like all of our work at the Institution, is dedicated to the increase and diffusion of knowledge.