What It Means to Live Life Working in the U.S. on a Visa

A piece of paper affixed to a passport is the subject of a new Smithsonian online exhibit

:focal(536x96:537x97)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/3f/bc3ff3cf-f0ab-4a08-aa2a-f1acbb469680/rueegawarikargoddessofvisasweb.jpg)

A single United States visa category may seem like an esoteric topic for museum attention. In the introduction to the online art exhibit “H-1B,” curators from the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center explain the choice of subject:

For many, the H-1B visa is more than a piece of paper affixed in a passport. It determines so much of life in America and the opportunity to become an American.

This statement, while exact, undersells the point. For many of the South Asians who have immigrated to the United States since the 1960s, my parents included, the incredibly iconic H-1B is part of our diaspora’s founding lore.

My parents entered the U.S. from India under a similar program several decades ago. The H-1B visa has became representative of a particular kind of American opportunity. Reserved for educated workers with skills in science, technology, mathematics and engineering, the H-1B grants holders the temporary right to live and work in the U.S.

“What’s somewhat unique about [the H-1B] is that it’s one of only a handful of visas that are transitional. They allow people to come in on a temporary visa and then down the road adjust to a permanent visa,” says Marc Rosenblum, a deputy director at the Migration Policy Institute, an independent, nonpartisan think tank in Washington, D.C. “This has become the main way that people get employment green cards in the U.S. With other temporary visas, people aren’t allowed to make that adjustment.”

Because it offers a path to residency, in some countries, particularly India and China, the H-1B visa has become one of the most visible symbols of American opportunity. The annual quota is 65,000, but the number of applicants is always higher. Since 2008, this surfeit of demand has been resolved through a lottery system—fair, maybe, but capricious and indecipherable. Many of the applicants are already living and working in the United States, often on student visas. Their employers, who sponsor their H-1B applications, must first demonstrate that no capable American workers can do the job.

The high demand, the limited supply, the difficult process, and the gleaming and distant promise of a better life—for professional migrants, these are the things the H-1B visa represents. Because the visa permits only the educated, those who snare a precious H-1B are often model would-be citizens. The program has garnered a chorus of critics for a number of reasons, including a concern over worker exploitation and job displacement.

But the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center’s online exhibit doesn’t dwell on the numbers of applicants, or their level of professional success. Instead, it focuses on the human side of the H-1B applicant experience, as seen through the eyes of 17 artists who have experience with the visa process. As their works demonstrate, applying for, getting and living on the coveted H-1B visa—or one of its related visas—is a journey of hope, but also one of isolation and challenge.

Arjun Rihan saw the solicitation for submissions of artworks for the show just after he finally received the green card that authorized him to live and work permanently in the United States. By then, he had been a ‘temporary’ resident of the United States for nearly 20 years, first as a student on scholarship at Stanford University, and later as a computer scientist and animator. His first visa depended on his student status, but several later ones were H-1Bs. He lived the American dream, but he also documented every minute of it for immigration officials. The paperwork was daunting.

“I have binders of stuff, because I was so paranoid of throwing something away and that document being important years later,” he says. “I always felt like this paperwork was kind of an autobiography.”

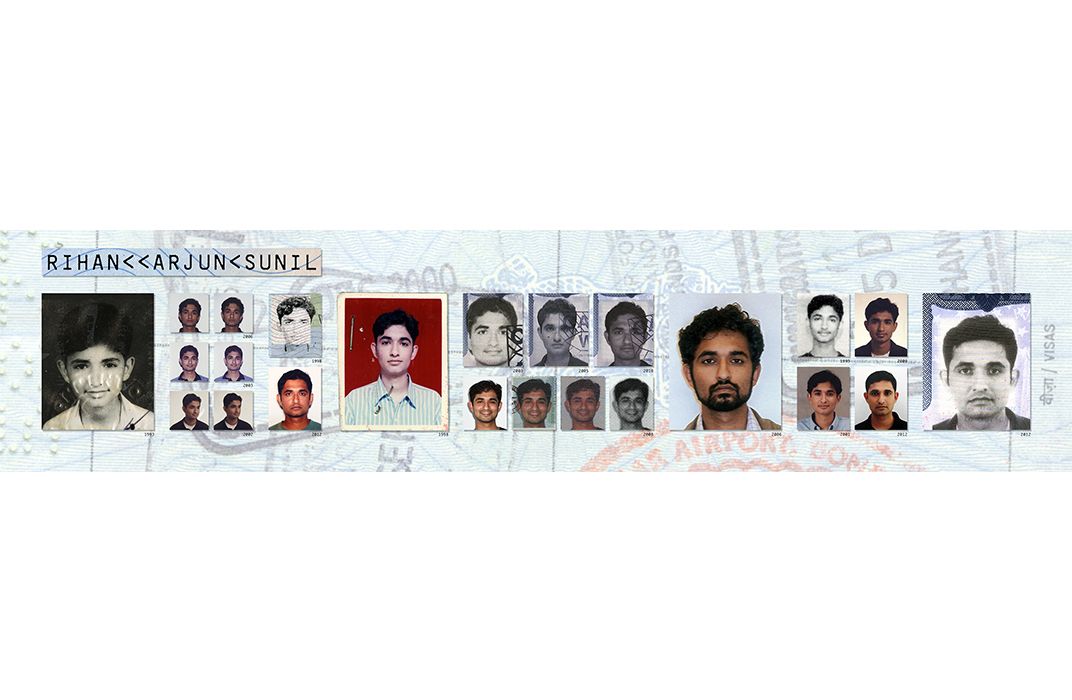

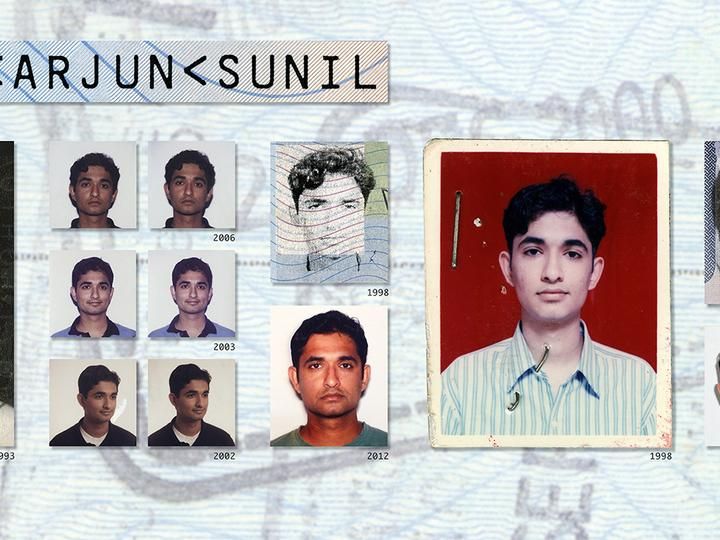

Rihan’s piece titled Passport-Sized Portraits is a masterpiece in understatement—an assemblage of 23 old passport photos, presented with no context but the dates they were taken. One of these photos, deeply arresting, embodies the artwork’s conceit. The picture is from 1998, and features Rihan’s calm face against a vivid red backdrop. The only thing that mars the picture is the snaggletooth of a staple that pokes through the artist’s throat, from the time Rihan stapled the photo to his first U.S. visa application—for the student visa that took him to Stanford.

“It was a huge moment of pride and achievement for me, but you don’t get that, it’s just another picture,” says Rihan, who explains further the divide between the picture’s reality and his own: “what you stand for is so different from this representation of you, and yet this representation of you drives so many of the big decisions that shape that other stuff.”

The photos in Rihan’s piece span 19 years, but in their staged sparseness, they reveal very little about the person in them. Rihan’s existence is magnified by omission; where are his friends, his houses, his co-workers? And yet, as he points out, these are the photos that helped officials decide his fate.

Other artists, when faced with this indecipherable process, this system that is both a border and a limbo, might ascribe mystical powers to what occurs in the margins of the immigration process.

In The Goddess of Visas, Ruee Gawarikar compares the visa application process to a prayer. In the center of Gawarikar’s painting, a multi-armed goddess brandishes a keyboard and what looks like a pen. Gawarikar’s painting is a nod to ancient Hindu art, well known for its vibrant and powerful deities. Of course, in traditional Hindu paintings, the Gods clutched weapons or scrolls.

The goddess of visas, with her keyboard and pen, is prosaic by contrast, but perhaps more powerful for it. In older paintings, Hindu goddesses were depicted standing on the heads of demons they had conquered, and the goddess of visas places her feet on piles and piles of paperwork, which Gawarikar says she spent a great deal of time constructing.

“I often thought that the visa officers had more knowledge about me than myself,” says Gawarikar, who came to the United States on a dependent visa— an H-4—while her husband was on an H-1B. The holders of H-4 and other dependent visas enjoy an even less certain existence than those on the H-1B. Barred until recently from all employment, they relied on their spouses for support.

“I couldn’t work, I couldn’t have a social security number, I couldn’t open a bank account,” she says. “It was a completely dependent visa and I felt like it.”

The Goddess of Visas serves as clear proof of what the curators write in the exhibit’s introduction: “To be in the U.S. on an H-1B visa is to live a life of uncertainty.”

The visa holder’s sense of “uncertainty” is one of the emotional realities that the curators of the exhibit hoped to explore through evocative media like art, says curator Masum Momaya, who conceived and organized the show. In 2013, Gawarikar had submitted The Goddess of Visas for the 2014-2015 exhibition “Beyond Bollywood: Indian Americans Shape the Nation,” that Momaya also curated about the history of the Indian American community.

When that show opened, Momaya noticed that the artworks about visas immediately sparked “conversations around a variety of topics including the range of emotions associated with transnational migration, the complexities of navigating the immigration process and the place of human agency in the midst all of this.” They expanded the H-1B exhibit into its own online property, in the hopes of inspiring greater “empathy and understanding.”

“For our community and Asian immigrants in the United States more broadly, the H-1B and H-4 visas have impacted many people's lives,” says Momaya. “I wanted to share this impact through the first-person perspectives of the artists.”

For those of us born in the United States, including me, it may be difficult to understand what draws migrants—especially those with advanced professional skills—to brave such an extensive set of unknowns. Venus Sanghvi, one of the artists, attempts an answer: “I came to the United States to further my education and convert my dreams into reality.”

And yet, as I went through the artworks in this exhibit, the theme that stuck me the most profoundly was that of loss. It’s easy to picture migration as a one-way journey, and plenty of the artworks focus on the upward trajectories of prayer and aspiration. But part of the visa holder’s journey—which becomes the permanent immigrant’s life—is the constant backward glance. I identified deeply with Tanzila Ahmed, whose piece Borderless included “teardrops…Bangla words from my Nani’s letters.” Few phrases capture so perfectly the sadness inherent in our conversations with those whom we leave behind.

For me, this sadness eventually pulled me back to the United States, the place I was born. When I was 23, I moved to India to work as a journalist. Much as the United States had been for my parents a generation previously; India for me was a land of adventure and opportunity. It was brilliant, exciting and new. I stayed for five years and for a while, I considered staying longer. But my longing for home brought me back. To refer to what I experienced as “longing” is to cut it in half a thousand times, and still be left with something too large to understand. It was an ocean, and at times—especially in those liminal moments, like while shopping for American groceries in crowded Delhi markets, or calling my parents on Thanksgiving—the vastness of my longing for home left me gasping.

What I realized during my time in India is that immigrants don’t cross borders—they exist within them. The H-1B visa digital exhibit builds on the Asian Pacific American Center’s previous strengths in Asian diaspora exhibitions. It is an ambitious and heartfelt outing in that it seeks to appreciate the border as its own space, with its own rules, its own vagaries, and its own profound emotional currents. The exhibit offers, in bright and shining detail, what the official visa forms do not: the margins, where life actually exists.

The new online exhibition titled “H-1B,” featuring the works of 17 artists and marking the 25th anniversary of the U.S. immigration program, was created by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anika-gupta-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/anika-gupta-240.jpg)