What the Handwriting Says About the Artist

A new exhibition by the Archives of American Art examines the handwriting of more than 40 American artists

Note Georgia O’Keeffe’s signature squiggle in this 1939 letter featured in the exhibition, “The Art of Handwriting.” Image courtesy of Archives of American Art

The American painter Charles E. Burchfield once said of handwriting: “Let the mind rule the writing not the eye … someone will decipher your hieroglyphics.” Whether impeccable cursive or illegible chicken scratch, an artist’s “hand” is never far from hieroglyphic. It is distinctive, expressive of the artist’s individuality—an art form in and of itself. The handwriting of more than 40 prominent American artists is the subject of “The Art of Handwriting,” a new exhibition by the Archives of American Art.

Housed in the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery at the Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture, “The Art of Handwriting” is guided by the notion that artists never stop being creative. “Being an artist carries through in all aspects of your life,” says curator Mary Savig. “Their creativity is lived and breathed through everything they do, and that includes writing letters.”

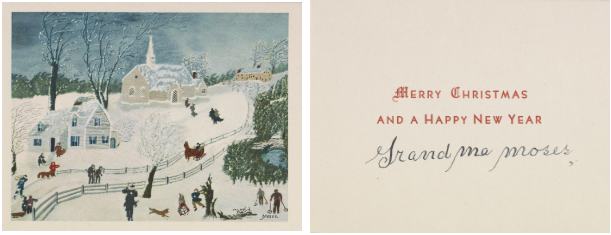

“The solitary Christmas card signature is evidence that Moses could turn out a cultivated script when she took the time,” writes Leslie Umberger, curator of folk and self-taught art at the American Art Museum. Image courtesy of Archives of American Art

For each letter, note and postcard in the exhibition, a scholar explains how the formal qualities of the artist’s handwriting shed light on his or her style and personality. Curator Leslie Umberger of the American Art Museum finds in the “pleasant and practical” script of Grandma Moses her twin roles as artist and farmwife. For National Gallery of Art curator Sarah Greenough, Georgia O’Keeffe’s distinctive squiggles and disregard for grammar reveal the spirit of an iconoclast. And author Jayne Merkel observes that Eero Saarinen displayed as much variety in his handwriting as he did in his architecture.

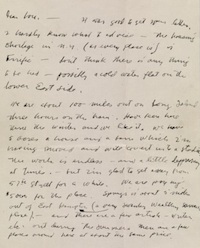

Jackson Pollock’s irregular schooling may explain his messy penmanship. Image courtesy of Archives of American Art

In some cases, an artist’s handwriting seems to contradict his or her artwork. Dan Flavin, for instance, was known for his minimalist installations of fluorescent lights but wrote in a surprisingly elaborate, traditional cursive. Art historian Tiffany Bell attributes the discrepancy to Flavin’s interest in 19th-century landscape painting. “Artists don’t live in vacuums,” says Mary Savig. “They’re really inspired by the art history that came before them.”

They are also shaped by their schooling. Many artists learned to write and draw by rote, practicing the Palmer method and sketching still lifes until they became second nature. Jackson Pollock is one exception that proves the rule: according to Pollock expert Helen Harrison, the artist’s messy scrawl had as much to do with his sporadic education as with his nascent creativity.

Handwriting may be a dying art, now that nationwide curriculum standards no longer require the teaching of cursive. Some have criticized the omission, citing the cognitive benefits of cursive instruction, while others argue that the digital revolution has rendered cursive obsolete. But for now, most visitors can still wax nostalgic over the loops and curlicues left behind by American artists.

Savig admits that her own handwriting looks more like Jackson Pollock’s than, say, the precise script of fiber artist Lenore Tawney. The variety of styles in the exhibition suggests that artists really are, she jokes, just like us: “Hopefully there’s a letter in here that is for every single person.”