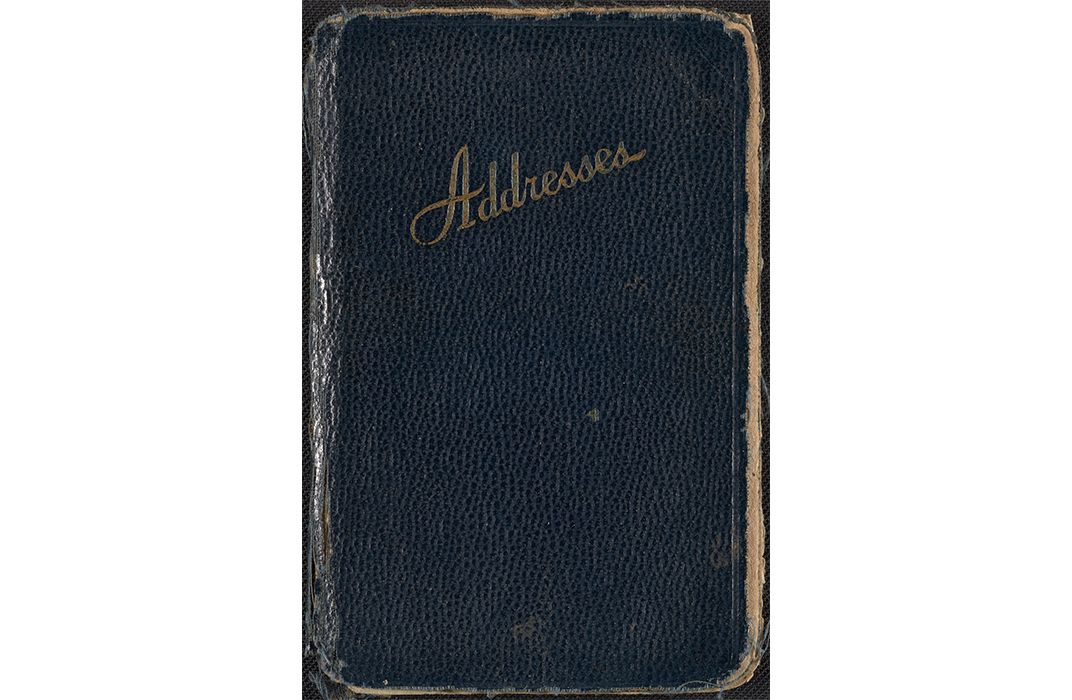

What’s Inside Jackson Pollock’s Address Book?

A new exhibition reveals the intimate details inside the “little black books” of some of America’s great artists

:focal(209x153:210x154)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c4/9e/c49e69b3-1e44-4620-8aaa-33a0b45f3db0/aaapollockweb.jpg)

The "little black book" is where the most intimate, mysterious details were once kept—a femme fatale’s list of lovers, a business magnate’s key clients, a detective’s codenamed informants. These unadorned volumes, where a person would jot down contacts and other personal details, is less coherent than a diary, but its scattering of names, numbers and appointments is in some ways more intriguing.

While these ledgers held an imaginative power (thanks to romances and noir films) often out of proportion to their actual daily use, an artist’s address book does provide a fascinating peek into their daily lives and the company they kept. That is the idea behind the new exhibition “Little Black Books,” currently on view at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art’s Fleischman Gallery.

“The title is really provocative to certain generations, because the idea of a ‘little black book’ in pop culture often refers to a book of love affairs,” says Mary Savig, the Archives’ curator of manuscripts, though she acknowledges that for the show she aimed to give the term broader connotations than only romantic ones. “But when we asked [people]—who are all born in the 90s—about what they thought a ‘little black book’ is, they had never heard of it before.”

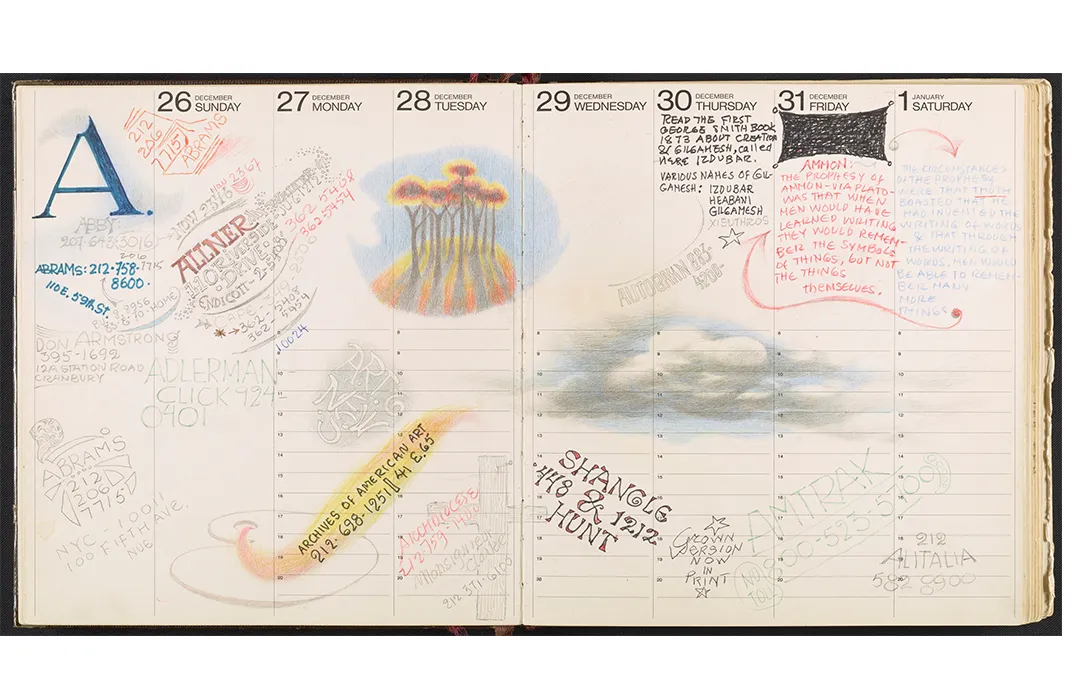

The show dives into the personal address books—complete with enigmatic notes, strikethroughs, and ink stains—of artists like Jackson Pollock and Joseph Cornell. The books offer a glimpse into the personal lives of these luminaries, and a portal into a time when important private information was scribbled into a modest volume, and carried around, unsecured and dog-eared.

A quirk of the books is how close friends and family are on equal footing with casual acquaintances. In her address book, art critic Lucy Lippard allots as much space to the entry for her husband as she does for one-time only acquaintances. A stranger flipping through the pages would have no idea who holds more significance in her life—which presented a challenge to the show’s curator.

“It really requires more research to figure out what those connections are and the depth of the relationships,” says Savig.

With this in mind, the exhibition explores the techniques historians might use to tease out the relationships contained in the books, digging into further archives, delving into the owner’s personal papers and notes.

Jackson Pollock’s book, which he shared with partner and fellow painter Lee Krasner, includes an impressive, if predictable, cast of characters, including abstract expressionists Mark Rothko and Helen Frankenthaler, and art critic Clement Greenberg. But it also included names of several doctors, among them Dr. Elizabeth Hubbard a psychotherapist; and Dr. Ruth Fox, a homeopathic practitioner who tried to cure Pollock of his alcoholism in the 1950s (and who wrote a condolence letter to Lee Krasner upon Pollock’s death).

Also, among the painter’s contacts were Vashi and Veena, a pair of Hindu dancers who met Pollock while on break from studying at Black Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina. Savig and her team were able to figure out who the doctors were by doing additional research in the Archives and through historical newspaper clippings and learned about the dancers through an oral history interview with Pollock’s friend, the painter Emerson Woelffer, who introduced them.

“These are certainly not household names and the only reason we could figure out who they are is because we have letters and other documents about them in the papers,” says Savig, adding that the research process was far more complicated than a simple Google search.

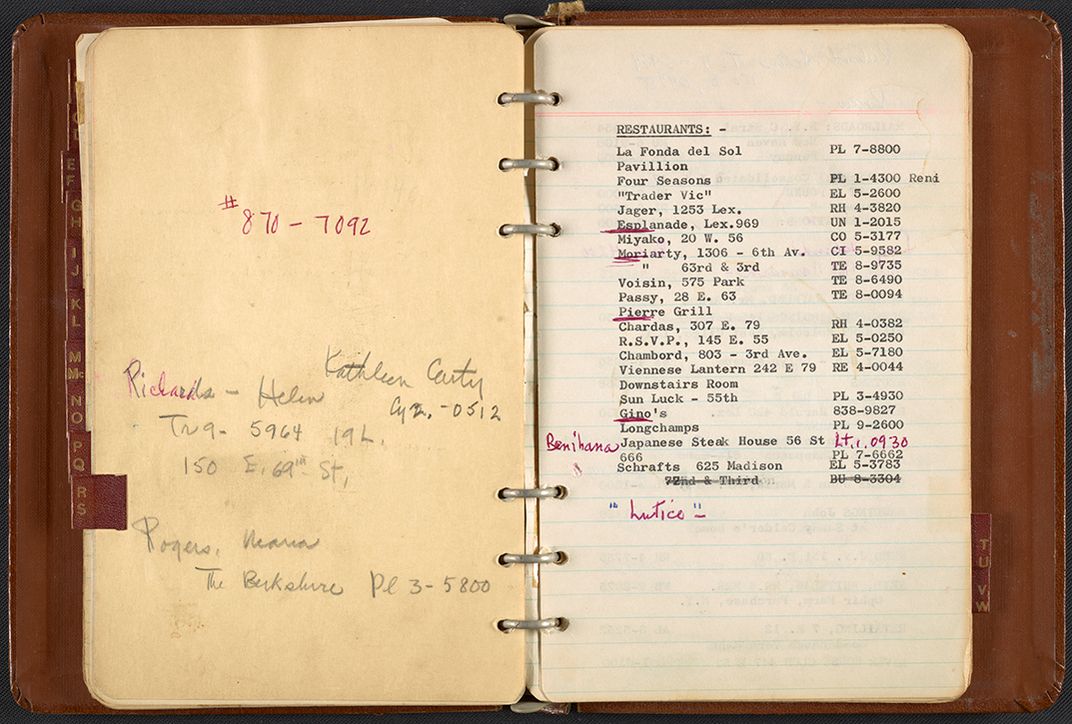

This blend of contacts famous and obscure, intimate and inconsequential, Savig says, provides an unusual way for historians to understand the book’s owner. Textile designer and weaver Dorothy Liebes' book eschews traditional alphabetical order. She instead breaks it up into particular categories: “Philadelphia,” “restaurants,” “boys” and an enigmatic category that she labels “extra girls.”

“Maybe when she went to Philadelphia, those were the only names she needed—hotels and airlines—but it’s her own order,” says Savig. “Sometimes we can figure out [the owner’s intention], but sometimes we never know. There are ‘extra girls,’ but no original ‘girls.’”

It was actually the story of a lost address book that gave Savig the idea for the show—as she attended a lecture discussing French conceptual artist Sophie Calle’s 1983 work The Address Book.

Calle had found a little black book on a Paris street and began contacting the names it contained to create a series of articles and photographs following the web of the owner’s family, friends and acquaintances. The show raised “an interesting question of what the connections are between all the people in an address book,” as Savig puts it.

Following the paper trail of connections and interactions, Savig and her team pieced together the web of relationships in the lives of these individuals. The show is composed of a series of glass cases, most of which contain a particular address book, accompanied by archival material that explores the broader context of its owner, the names included and the social circles they represent.

But the first case in the show serves a more straightforward purpose: explaining what defines a “little black book,” a concept has slipped from pop culture in this era of smartphones and social media.

“People growing up, getting new things in their life—going to college and moving, or getting a new job and moving—we don’t really track that physically now,” she says.

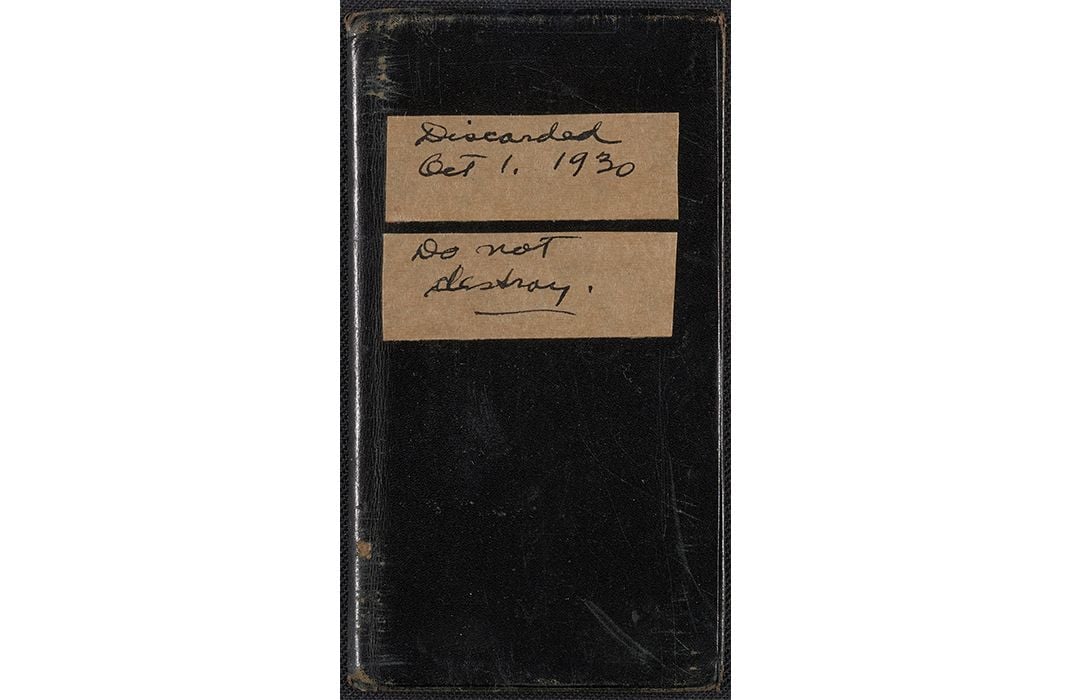

The books in the show reveal the constant shifts of these artists’ social networks. Walt Kuhn, painter and organizer of the 1913 Armory Show, had six or seven small books (though only one is on view in the exhibit). When he got a new book, he would transfer the important information from the original book, effectively leaving behind contacts that no longer held as much importance in his life (the pre-Facebook version of “unfriending”).

“Maybe they didn’t need to stay in touch anymore, but you can see how contacts are prioritized in that way,” says Savig. On the book in the show, he writes, “discarded October 1, 1930, do not destroy.”

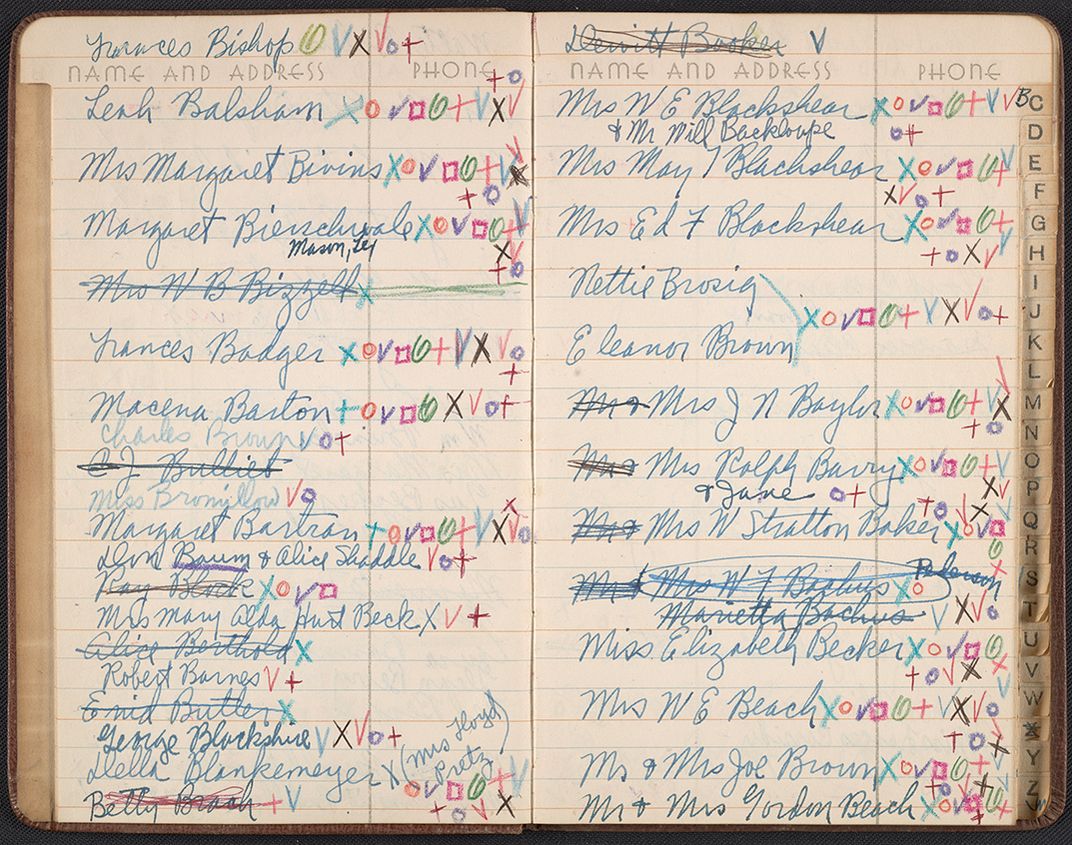

Printmaker Kathleen Blackshear had an address book for her holiday card mailing list. She made a beautiful silkscreen print holiday card each year, and crossed off names from one year to the next. She would add a symbol next to some names to indicate if they got a card that year, and received many cards in return. “Maybe she took people’s names off the list if they didn’t send her a card in return,” considers Savig.

Just as an address book provides a vehicle through which to understand a person, it also served in one case as a pathway to a much larger world for its owner. Assemblage artist Joseph Cornell was a known recluse, who rarely left his home in Flushing, New York. But his address book is packed with names of avant-garde artists with whom he frequently exchanged letters and gifts, many of which he used in his collages.

“Even though Cornell never really left New York, he did accumulate through all his friends and people listed in his address book, all these experiences from around the world,” says Savig. “People really enjoyed corresponding with him. They brought the world to him. He didn’t leave much but still had a really interesting life through those relationships.”

Little Black Books: Address Books From the Archives of American Art is on view through November 1, 2015 at the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery located at 8th and F Streets NW, home also to the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)