When Concorde First Flew, It Was a Supersonic Sight to Behold

The aircraft was a technological masterpiece, but at one ton of fuel per passenger, it had a devastating ecological footprint

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/95/5b/955b52ed-22ff-4614-ab05-bcece157290d/a20030139000cp09web.jpg)

On January 21, 1976, two of what many aviation enthusiasts consider the most beautiful man-made object ever to fly—took off simultaneously from Heathrow Airport near London and Orly Airport near Paris with their first paying passengers. Those two airplanes, called Concorde, would fly faster than the speed of sound from London to Bahrain and from Paris to Rio de Janeiro, elegant harbingers of a brave new era in commercial air travel.

One of the three Concordes on public view in the United States stands regally in the hangar of Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia, the red, white, and blue colors of Air France emblazoned on its vertical stabilizer. (The other two are at the Intrepid Museum in New York City and the Museum of Flight in Seattle.)

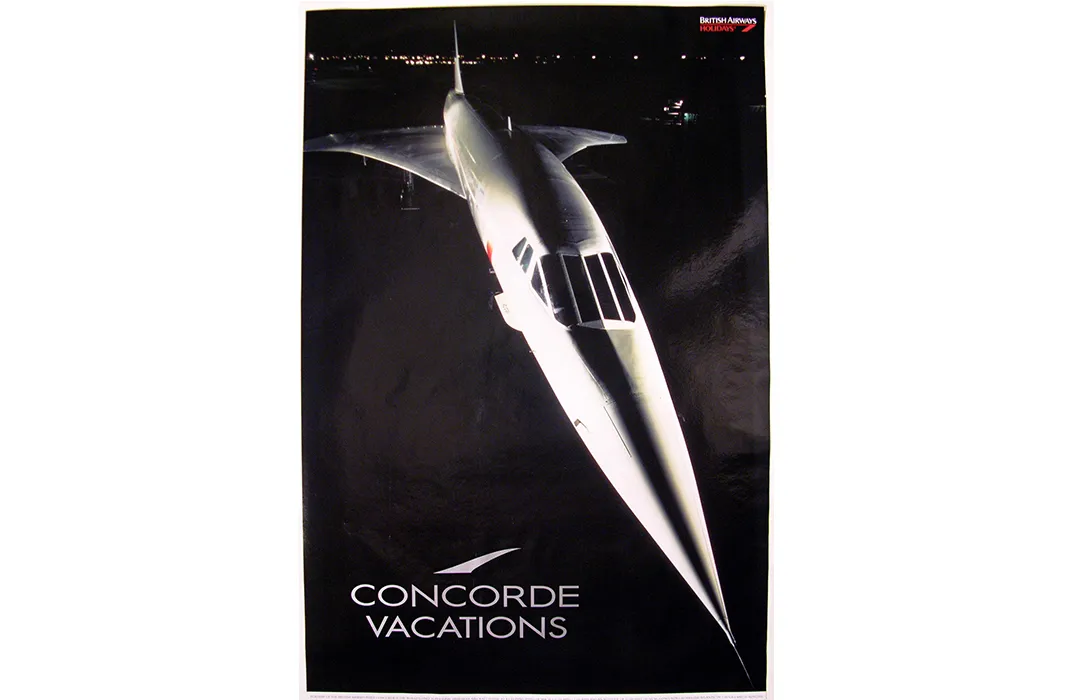

The performance of Concorde—airline pilot and author Patrick Smith tells me that one does not put a “the” in front of the plane’s name—was spectacular. Able to cruise at a near-stratospheric altitude of 60,000 feet at 1350 miles per hour, the plane cut travel times on its routes in half. But speed and altitude were not the only factors that made Concorde so remarkable. The plane was a beauty.

Since back when flight was only a dream, there has been an aesthetic element in imagined flying machines. It’s easy to imagine Daedalus fixing feathers onto the arms of his doomed son Icarus in a visually appealing, bird-like pattern. Leonardo da Vinci envisioned the symmetrical shape of a bat wing in his drawings of possible airplanes. Some of this aesthetic is still carried over (ironically perhaps) in military fighter jets, but in commercial aviation, where profit demands more and more passengers, aircraft designers have swapped beauty for capacity.

The workhorse 747, for instance, looks like a plane sculpted by Botero. At a time when airliners are called buses, Concorde, designed by Bill Strang and Lucien Servanty, was the dream of Daedalus come true. It seemed to embody the miracle of flight, long after that miracle was taken for granted. In my book on elegant industrial designs, the graceful creature occupies a two-page spread.

ABC Breaking News | Latest News Videos

Concorde was one competitor in a three-team international race. In the U.S., Boeing won a design face-off with Lockheed for a supersonic airliner, but, according to Bob van der Linden, curator of air transportation and special purpose aircraft at the Air and Space Museum, Wall Street never invested in the U.S. version, and Congress turned down the funding necessary to build the plane for a combination of budget and environmental reasons.

Russia also entered the foray and produced the TU-144, a plane that looked somewhat similar to Concorde, and beat the Anglo-French plane into the air by a few months in December of 1968. The ill-fated Russian SST crashed during a demonstration flight at the Paris Air Show in 1973, and never flew again.

Concorde began test flights early in 1969 and—with pilots and crews specially trained and engineering honed—began carrying paying passengers in 1976. (And pay they did, with a first class ticket costing around $12,000.)

Smith, author of the blog “Ask the Pilot” and of the book Cockpit Confidential, told me that the sleek supersonic transport (SST) was “a difficult plane to engineer, and just as difficult to fly.” But, he continued, Concorde was an engineering triumph, a formidably complex machine “all done with slide rules.” Despite the cost of tickets, the plane was not luxurious inside, seating only about 144, with a single aisle in constant use by the aircrew needing to serve meals in half the usual time. A story, possibly apocryphal, tells of a passenger who was asked by the captain on debarkation how she liked Concorde: “It’s so ordinary,” she complained. An SST engineer, hearing this, responded: “That was the hardest part.”

Between 14 and 16 of the French and British Concordes made an average of two flights a day for several years. Smith says the plane’s stellar safety record was “more the work of probability than engineering. It’s possible that with a significantly larger number of Concordes on the roster of the world’s carriers, there would have been an altogether different safety record.”

That safety record came to a terrible end on July 25, 2000. On takeoff from Paris, a flaming tail of fire followed Flight 4590 into the air, and seconds later the Air France Concorde crashed, killing all aboard, 109 passengers and crew members and four people on the ground. Initial reports blamed a piece of metal that had fallen off a Continental DC-10 taking off just ahead of Concorde and caused pieces of a blown tire to pierce the fuel tank.

Later investigations told a more complicated story, one that involved a cascade of human errors. The plane was over its recommended takeoff weight, and a last minute addition of baggage shifted the center of gravity farther back than normal, both of which changed the takeoff characteristics.

Many experts speculate that if it hadn’t been for the additional weight, Flight 4590 would have been in the air before reaching the damaging metal debris. After the tire was damaged, the plane skidded toward the edge of the runway, and the pilot, wanting to avoid losing control on the ground, lifted off at too slow a speed.

There is also a prevailing opinion that the engine fire that looks so disastrous in photos taken from an airliner next to the runway would have blown out once the plane was in the air. But apparently the flight engineer shut down another engine in an unnecessary abundance of caution, making the plane unflyable.

Perhaps because an unlikely coincidence of factors caused the crash, Concorde continued in service after modifications to the fuel tanks. But both countries permanently grounded the fleet in 2003.

In the end, the problem was not mechanical but financial. Concorde was a gorgeous glutton, burning twice as much fuel as other airliners, and was expensive to maintain.

According to curator Van der Linden, for a trans-Atlantic flight, the plane used one ton of fuel for each passenger seat. He also points out that many of the plane’s passengers didn’t pay in full for their seats, instead using mileage upgrades. Just as Wall Street had failed to invest in the plane, other airlines never ordered more Concordes, meaning that the governments of Britain and France were footing all the bills, and losing money despite the burnishing of national pride.

“The plane was a technological masterpiece,” says the curator, “but an economic black hole.”

In 1989, on the bicentennial of the French Revolution, when French officials came to the States to present the U.S. with a copy of the Declaration of the Rights of Man, an agreement was struck with the Smithsonian to present the Institution with one of the Concordes when the planes were finally phased out.

“We figured that wouldn’t be for many years,” says Van der Linden, who has edited a soon-to-be-released book called Milestones of Flight. “But in April of 2003, we got a call that our airplane would be coming. Luckily, it was just when the Udvar-Hazy Center was opening, and we managed to find room on the hangar floor. There was some initial worry that such a long aircraft would block access to other exhibits, but the plane stands so high that we could drive a truck under the nose.”

On June 12, 2003, the Smithsonian Concorde left Paris for Washington, D.C. Van der Linden happened to be in Paris on other business at the time, and was invited to fly gratis along with 50 VIPs. “We flew at between 55,000 and 60,000 feet, and at that altitude the sky, seen through the hand-size window, was a wonderful dark purple. One other great thing about the flight was that U.S. taxpayers didn’t have to pay for my trip home.”

Two months later, with the help of Boeing crews, the extraordinary plane was towed into place, and now commands the southern end of the building. Though first built more than four decades ago, Concorde still looks like the future. As Patrick Smith told me, “Concorde evoked a lot of things—a bird, a woman’s body, an origami mantis—but it never looked old. And had it remained in service that would still be true today.

‘Timeless’ is such an overused word, but very few things in the world of industrial design can still appear modern 50 years after their blueprints were first drawn up.”

In what is perhaps an inevitable post-script to the commercial SST era, a group that calls itself Club Concorde has come up with the nostalgic dream of buying one of the mothballed SSTs and putting it into service again for those who consider time money, and have plenty of money to spare.

According to newspaper reports in England, the club has so far raised $200 million to restore former glory aloft, and has approached current owner Airbus to buy one of that company’s planes.

The suggestion has met with a “talk to the hand” response. French officials have compared Concorde to the Mona Lisa (an apt da Vinci reference) as a national treasure, not to be sold off. And the expense and difficulty of resurrecting the plane, even if it could be purchased, are formidable obstacles.

David Kaminsky-Morrow, the air transport editor of Flightglobal.com, points out that “Concorde is an immensely complex supersonic aircraft and [civil aviation authorities] will not entrust the safe upkeep of its airframe to a group of enthusiasts without this technical support in place.”

So all those who missed the boat (or rather, the bird) when Concordes were still flying can still go to the Udvar-Hazy Center to exercise their right to gawk admiringly at a true milestone of flight.

Concorde is on display in the Boeing Aviation Hangar at the Smithsonian's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, Chantilly, Virginia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)