Wyoming Is Turning a Former Cold War Nuclear Missile Site Into a Tourist Attraction

The U.S. Air Force is working to recreate a Cold War stronghold

It’s been over a decade since the U.S. military decommissioned the last Peacekeeper missile. But Lt. Col. Peter Aguirre can still recall the musty smell of military-grade paint and stagnant air that defined his long stays inside one of the missile alert facilities built beneath the F. E. Warren Air Force Base near Cheyenne, Wyoming. Aguirre’s workday started with a journey 100 feet below ground—a trip that visitors will soon be able to experience for themselves.

Officials from the U.S. Air Force and the State of Wyoming are working to capture every detail of the sole remaining Peacekeeper missile alert facility, Quebec-01—a Cold War stronghold with a chilling past. “It’s difficult to explain the sense you have down there, but it’s a lot like being in a submarine,” Aguirre tells Smithsonian.com. “The sounds and smells you never forget.”

Aguirre and a team of crewmembers of the 400th Missile Squadron babysat the Peacekeepers, once the Air Force’s most powerful weapons, and were responsible for detonating the missiles should the time ever come (fortunately, it never did). Equipped with up to ten warheads each, the Peacekeepers stood 71 feet high and weighed 195,000 pounds. With a reach of approximately 6,000 miles, the missiles served as a towering reminder to the Soviet Union that the United States was prepared for all-out nuclear war at any time.

Watching over a missile might sound like a simple job, but it came with plenty of risks. Although the underground facility was protected by massive steel doors and concrete, there was always the chance that something could go wrong during a detonation. To help mitigate these risks, the military equipped each bunker with an escape tunnel—and told missilers that, in the worst-case scenario, they could dig themselves out with shovels.

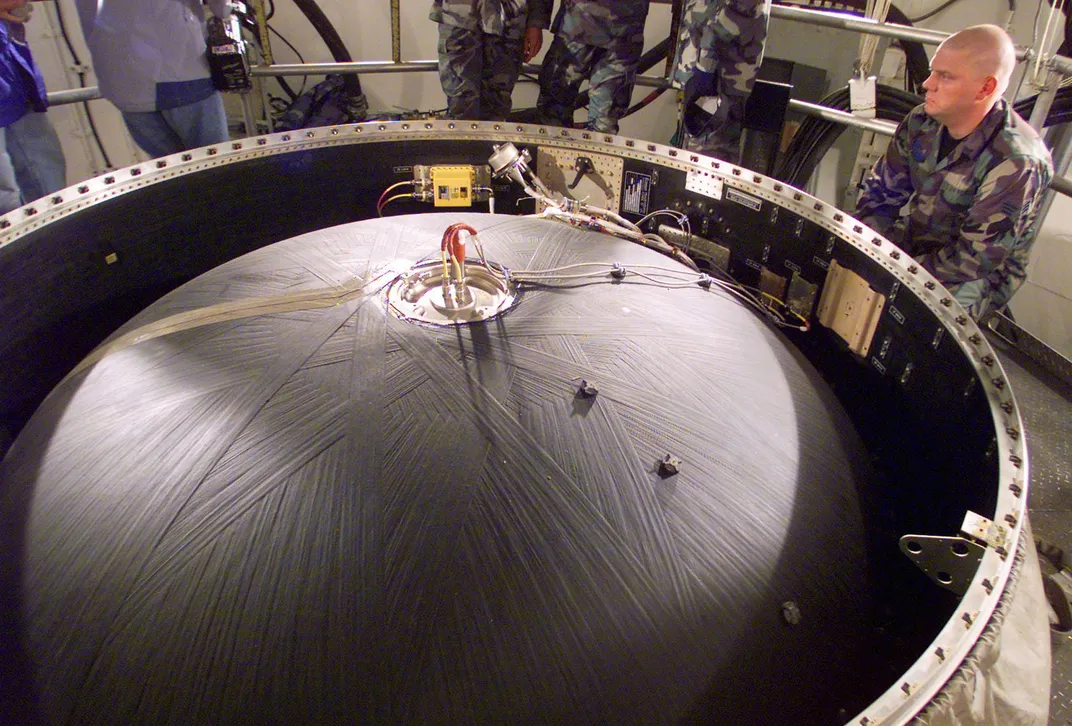

During the Cold War, the base served as ground zero for the Air Force's nuclear arsenal, housing the nation's most powerful and sophisticated missiles from 1986 to 2005. The Peacekeeper was eventually decommissioned as part of the bilateral Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START II Treaty). In the decade since, the Air Force has carted away any remaining warheads and missile components from the site, filled the remaining missile silos with cement and disabled the underground alert facilities. Now, it’s working to rehabilitate and recreate the experience of what it was like to visit Quebec-01, from the 100-foot elevator ride underground to the massive four-foot-wide blast doors designed to protect personnel if ever there was a detonation.

Currently, workers are restoring and reinstalling all of the equipment once housed inside Quebec-01 to make it look like it did when it was fully operational (sans missiles, of course). If all goes according to plan, the Air Force will transfer the site to the Wyoming State Parks & Cultural Resources agency in 2017 to ready it for public use, with an anticipated opening date of 2019. Though tour planning is still in process, visitors should be able to make underground visits to Quebec-01 on tours led by former missilers serving as docents.

“The Cold War was a huge part of U.S. history, especially for the Baby Boomer generation who lived through it,” Milward Simpson, director of Wyoming State Parks & Cultural Resources, tells Smithsonian.com. “Nuclear tourism is something that has an increasing interest in the public, and it’s extremely important that we preserve that history, especially since the Peacekeeper was one of the factors that helped end the Cold War.”

Although the Peacekeeper can’t take sole credit for the end of the Cold War—other factors were at play, including the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Soviet Bloc—it was used at the bargaining table between countries. Ronald Sega, undersecretary of the Air Force, once remarked that the weapon served as “a great stabilizing force in an increasingly unstable world.” But the Peacekeeper’s heyday didn’t last: The weapons were eventually replaced with RV Minuteman III missiles at bases across the country as part of the U.S. Air Force’s current ICBM program.

When it finally opens to the public, Quebec-01 will join a growing group of preserved missile sites, including the Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile Site in North Dakota, the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota and the Missile Site Park in Weld County just outside of Greeley, Colorado. In addition, the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force near Dayton, Ohio, houses a (deactivated) Peacekeeper missile.

Some may balk at the idea of visiting a facility that once housed nuclear weapons, but Travis Beckwith, cultural resources manager with the base’s 90th Civil Engineering Squadron, tells Smithsonian.com that the government will run environmental baseline surveys to ensure that the site is safe for visitors. So far, none have found nuclear contamination in the soil.

“We’re in the process of doing those surveys right now,” Beckwith says. “Our chief concern is any possible contamination.” Since the missiles were built elsewhere and strong solvents were never used inside the enclosed missile alert facilities to maintain them, the military is focusing its remediation efforts on removing asbestos, lead-based paint and other contaminants commonly used in older construction projects instead.

When it opens to the public, the site will contain no traces of actual weaponry. But that doesn’t mean it will be any less authentic. “At one time, very few people in the world could say that they had the experience of going to an underground missile alert facility,” Simpson says. “Soon visitors to Quebec-01 will be able to see it like the missilers once did, right down to the blast-door graffiti they left behind.”

Just like fighter pilots, who painted “nose cone art” on their jets during wartime, missilers left indelible marks of their own within the missile alert facility, or “capsule.” One drawing in particular caught Simpson’s eye during a recent walkthrough: a doodle of a pizza box with the words “guaranteed in 30 minutes or less”—a nod to the length of time it would take a Peacekeeper to reach its intended target across the pond.

The experience left marks on missilers, too. Aguirre still remembers working on September 11—the only time he ever thought he might have to detonate a missile. "[I was] dead asleep when it happened, and my deputy woke me up," he says. "I didn’t know what was going to happen, and out of all the moments in my life, quite frankly that was the most terrorizing."

Now that all of the Peacekeepers have been removed from the base, he’s been reassigned and serves as director of operations for Task Force 214, but his years as a missiler remain seared into his memory. “It was a very surreal moment for me,” says Aguirre of his recent revisit to the facility. “It’s strange to think that people will go down there to do tours, but it’s also awesome that the country is allowing access to this historic site.” Tucked 100 feet beneath the earth and surrounded by weapons consoles, memorabilia and alert systems, it may be hard to remember that the Cold War ever ended.

Peacekeeper statistics

• The U.S. military commissioned the Peacekeeper program from 1986 to 2005. The F. E. Warren Air Force Base was the only U.S. military base to house the missiles.

• Each Peacekeeper missile held up to ten independently targeted warheads, weighed about 195,000 pounds, stood 71 feet in height and had a diameter of seven feet, eight inches.

• The maximum speed of a Peacekeeper was approximately 15,000 mph, and it could travel the approximately 6,000 miles east from the United States to Russia, its target. Upon detonation, it would go through a four-part sequence that involved leaving and re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere before reaching its target in 30 minutes or less.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/8f/bc8f55f9-e1bf-4daa-a21e-9033b47b5115/rr013517.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/da/0b/da0b71dc-dc11-46f0-a452-f897daa6d922/df-st-98-03337.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/77/9c772ac8-26ab-4b3e-8020-f6d136c24f27/missile_alert_facility.jpg)