The Statues of Easter Island

A riddle of engineering hasn’t stopped archaeologists from debating how the giant carved stones were transported around the island

About 2,000 miles off the coast of South America sits the Chile-governed Easter Island. Just 14 miles long and 7 miles wide, it was named by Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen, who discovered it on Easter Sunday in 1722. Archaeologists and historians have debated the island's history, but it is believed that Polynesians landed on the island around A.D. 800 and depleted its resources until it was practically barren.

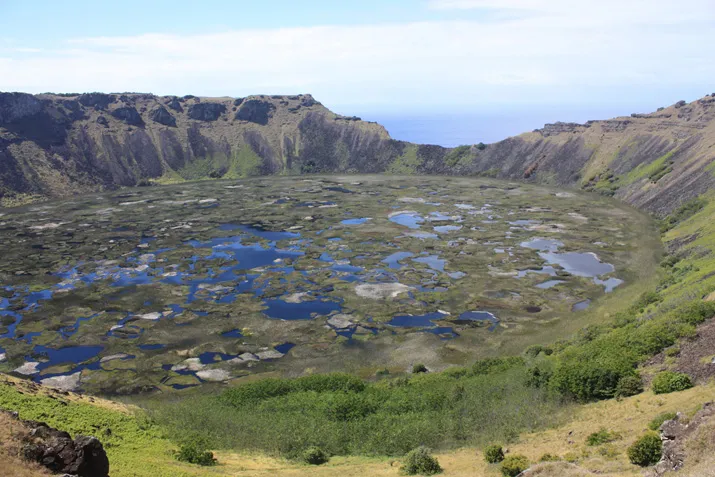

What they left behind, however, remains one of the most captivating riddles of engineering: nearly 1,000 monolithic statues. The massive effigies, on average 13 feet tall and weighing 14 tons, are thought to represent ancestral chiefs raised to the level of gods. According to archaeologist Jo Anne Van Tilburg—who is the founder of UCLA's Easter Island Statue Project and has studied the artifacts for nearly 30 years—about 95 percent of the statues were carved in the volcanic cone known as Rano Raraku. Master carvers, who taught their craft over generations, roughed out the statues using stone tools called toki and employed sharp obsidian tools to make finer lines.

The real mystery—how a small and isolated population managed to transport the megalithic structures to various ceremonial sites—has spawned decades of research and experiments. "It is amazing that an island society made of 10 to 12 chiefdoms had sufficient unity and ability to communicate carving standards, organize carving methods and achieve political rights of way ...to transport statues to every part of the island," Van Tilburg says.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.