Step Inside a Famous Submarine

Where to visit historic subs this summer—or ride in a modern one

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/25/7f/257fdae8-f14e-4de5-b3e3-cb88c5b944ea/42-28275659.jpg)

The idea of a ship that can travel underwater has been around far longer than the technology to make it possible. Famed inventor Leonardo da Vinci, who died in 1519, had an idea for a submersible vessel but kept his sketches a secret. He wouldn’t share them, he said, “because of the evil nature of men who practice assassination at the bottom of the sea.”

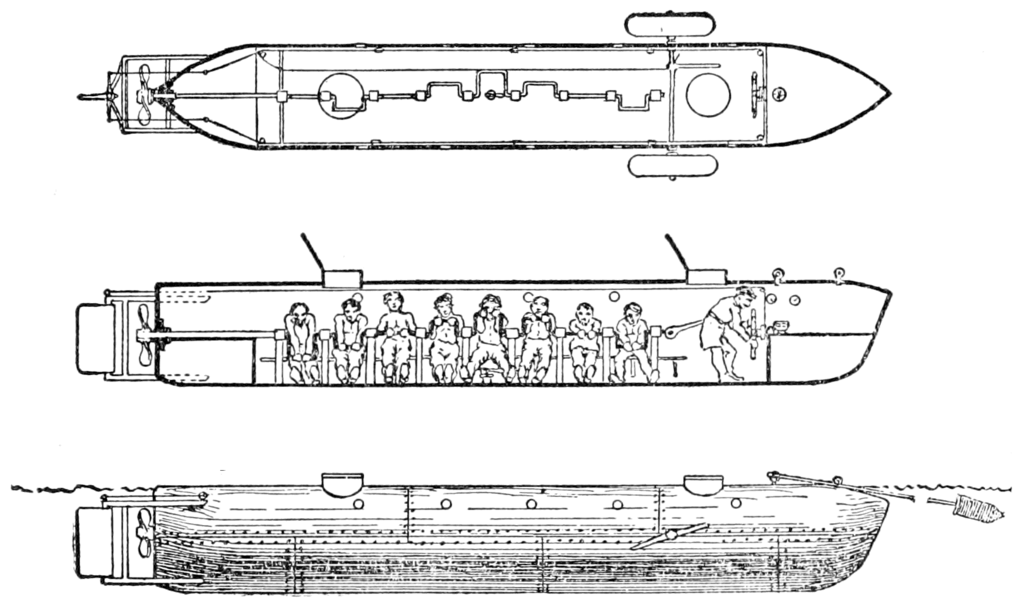

Da Vinci never constructed his machine, as far as we know, and it wasn’t until about 1723 that a submersible came to life. This craft worked 15 feet below the surface of the Thames River, and according to Tom Parrish, author of The Submarine, even King James I visited onboard, despite the risk of drowning. Other inventors continued to make rudimentary submersibles until finally, in 1775, a man named David Bushnell created a machine that fits Parrish’s definition of a submarine: a vessel that can propel itself on water but also underneath it, and that can sink and rise again at will. Still, only one person could squeeze into Bushnell’s ship, which Parrish writes looked like two bathtubs clamped together, or like the shell of a strange oyster.

Today, submarines can be hulking—such as the 574-foot-long Soviet Typhoon—or sleek and miniature, like this two-person sub that looks and moves remarkably like a killer whale. According to the company that sells it, the orca-styled submersible can be yours for $90,000.

For those who don’t want to join the Navy—or don’t have $90,000 lying around—there’s still hope for adventure. A host of famous submarines are on display around the world, ready for visitors to explore. And if you want to ride in one yourself, there are even some tourist submersibles that can take you underwater.

H. L. Hunley, North Charleston, South Carolina

To see the first combat submarine ever to sink an enemy ship—a big milestone in the history of warfare—visit the H. L. Hunley in North Charleston, South Carolina. The Hunley earned that inaugural honor during the Civil War, when it was built by the Confederate side and used in 1864 to attack the USS Housatonic with a 135-pound torpedo. The Hunley itself sank a little while later, under mysterious circumstances. For years afterward, explorers and treasure-seekers tried to locate the boat, and P.T. Barnum even offered a reward of $100,000. Still, no dice. Finally, on May 3, 1995—20 years ago this month—a team of archeologists funded by adventure novelist Clive Cussler finally found it. But to actually raise the sub from the ocean required a whole new kind of effort.

“Nobody has raised an entire ship before, so they had to go about figuring out how to do it,” Sherry Hambrick, who works for the nonprofit that now displays and preserves the Hunley, told Smithsonian.com. Luckily, the sub was in remarkable shape, Hambrick explained, because it had been buried relatively quickly in a layer of silt that protected it from salt erosion. In August 2000, the team dredged up the Hunley and found a much more impressive machine than they’d imagined rotting beneath the sea. The vessel included technology they had not expected to find, such as a flywheel designed to act as a break for the propeller—an advanced feature for its time.

The sub eventually went on display in North Charleston, where those who visit can learn not only about the vessel itself and the stories of its crew but about the technology used to recover it. Because the Hunley is so old and still being studied, however, visitors can’t enter inside.

USS Nautilus, Groton, Connecticut

The world's first nuclear-powered submarine marked another important milestone in underwater technology. During the Cold War, the United States aimed to build a more advanced sub than had ever been seen before, and found success with the USS Nautilus. Until 1954, as The New York Times explains, “submarines were basically surface ships that could submerge at slow speed for a few hours.” When the Nautilus joined the fleet on September 30 that year, it had the unprecedented ability to produce its own power and fresh water—allowing it to stay underwater for weeks instead of hours. The boat also shattered previous records of submarine speed and distance, and in 1958 completed Operation Sunshine, a secret voyage that made it the first sub to go to the North Pole.

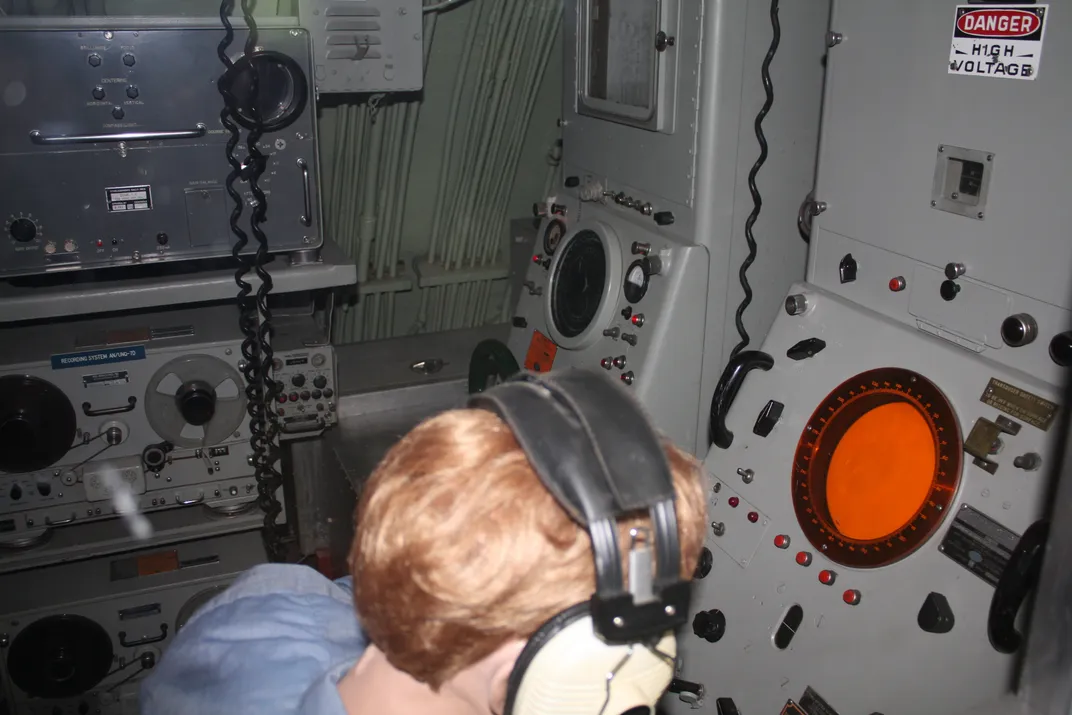

To explore the Nautilus, head to the Submarine Force Library and Museum in Groton, Connecticut, and take a tour inside. Unlike the Hunley, which is older and more fragile, visitors can walk through the various chambers. The Nautilus still has two torpedoes on display, and visitors can also step into the Attack Center to see the buttons, keyholes and other instruments used to launch the weapons. (According to the National Museum of the U.S. Navy, every submarine must shoot its weapons at least once as a demonstration. However, Navy archivists who searched through records for Smithsonian.com didn’t find evidence of the Nautilus ever firing on an actual target.) To get a feel for what it was like to live every day in this undersea vessel, visitors can tour some of the bunk beds and witness what little privacy the 11 officers and 105 enlisted men experienced each night and day. Pin-up photos of women still hang throughout the boat.

USS Cod, Cleveland, Ohio

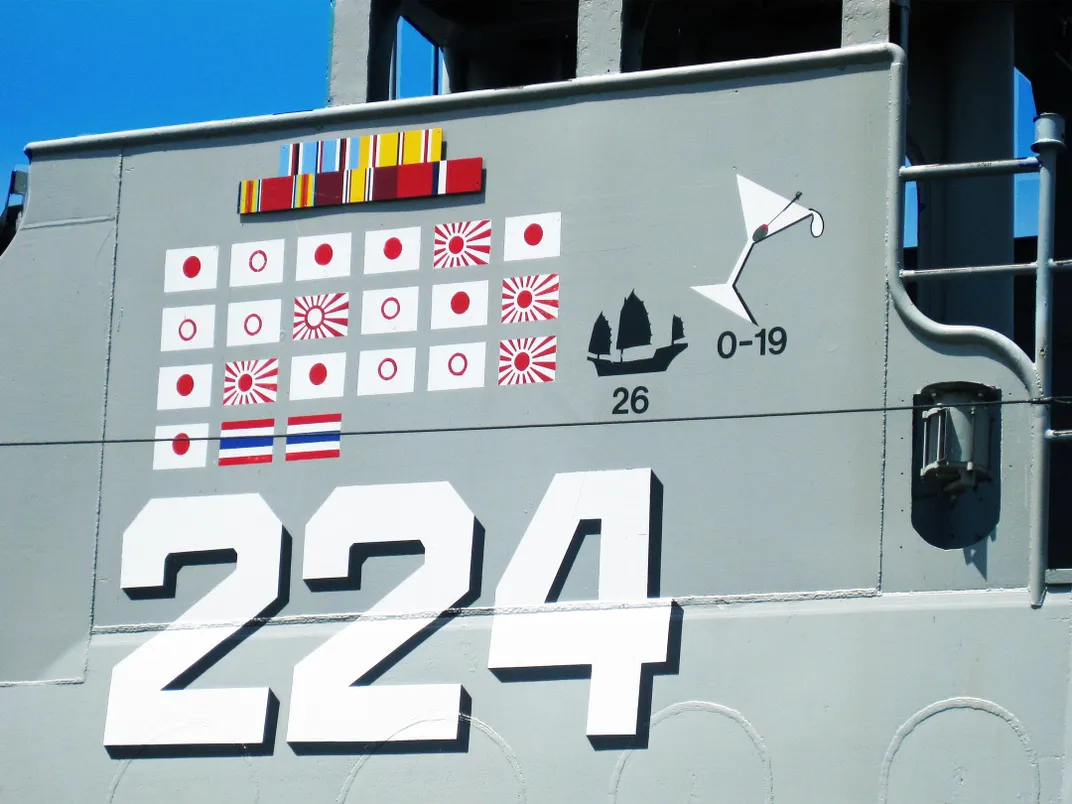

The USS Cod is the only submarine ever to have rescued the crew from another country’s sub, and this July the USS Cod Submarine Memorial in Cleveland will host a live reenactment for the 70th anniversary of the event. After fighting in several battles during World War II and destroying Japanese warships, the Cod made history in July 1945, after a Dutch sub named O-19 floundered on a coral reef in the South China Sea while heading toward the Philippines. The crew sent out a distress call, and the Cod arrived the next day to help. After spending two days trying to pull the O-19 free, both captains agreed it was hopeless. Instead, the Cod brought the 56 stranded Dutch sailors on board, then destroyed the coral-lodged sub with “two scuttling charges, two torpedoes, and 16 rounds from Cod's 5-inch deck gun.” After the historic assistance, Dutch sailors threw their rescuers a party, during which they got word that Japan had surrendered.

Take a Ride in a Modern Sub

Other submarines-turned-museums are scattered as far as India, Russia, Peru and Japan, each with their own story. (The one in India, for instance, named the INS Kursura, was built in Riga, in the former Soviet Union, and inducted into the Indian navy in 1969. After 31 years of use, it was decommissioned and put on display in Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh.)

Museum submarines tend to stay stationary, but there are plenty of options for riding inside more modern submersibles as a tourist. One company, U.S. Submarines, supplies vessels for visitors to plunge underwater in places such as Hawaii, Egypt, Bora-Bora and Taiwan. These tours often focus on the creatures you can see through the portholes, but on subs in places like the Cayman Islands, you can sometimes spy the vestiges of shipwrecks.

There are also much smaller, more adventurous options, such as a three-person submersible that offers a week-long tour of sunken ships off the coast of Sicily, and that even sometimes picks up artifacts from the sea floor. If that’s too much action, more leisurely tourist subs offer adults on board a drink. Though we can’t say what da Vinci might have made of all this, we’ve certainly come a long way since his drawings.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)