Captain Bligh’s Cursed Breadfruit

The biographer of William Bligh—he of the infamous mutiny on the Bounty—tracks him to Jamaica, still home to the versatile plant

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Castleton-Gardens-631.jpg)

An hour out of the maelstrom of Kingston's traffic, the first frigate bird appeared, and then, around a bend in the road, the sea. There are few beaches on this southeastern side of Jamaica, nothing resembling the white sands and resorts on the opposite shore, around Montego Bay. While Jamaicans might come to the village of Bath, where I was now headed, this part of the island is little visited by outsiders.

Six miles inland I and my guide Andreas Oberli—a Swiss-born botanist and horticulturist who has lived in Jamaica for nearly 30 years—arrived at Bath, seemingly deserted at this late morning hour. A pretty village of sagging, historic houses, it had formerly been a fashionable spa known for its hot springs; the 17th-century privateer Henry Morgan is reputed to have enjoyed the genteel practice of taking the waters. There are two reasons a visitor might come to Bath today: the springs and its botanical garden, which now, beyond its Victorian-looking iron gate, lay snoozing in the sun.

Unfolding lazily from the shade of the garden wall, a straggle of young men with ganja-glazed eyes leaned forward to scrutinize us as we approached. Inside the gate and beyond the sentinel of royal palms, few flowers bloomed, for this garden is given less to blossoms than to trees.

Elephant apple from India; Christmas palm from the Philippines; Ylang ylang from Indonesia; two aged tropical dragon's blood trees and a Barringtonia asiatica, believed to be 230 years old. The stark botanical labels hinted at the labor and eccentric vision that lay behind the garden. Established in 1779, Bath is one of the oldest botanical gardens in the world, its collection jump-started, in this time of English-French hostilities, by the capture of a French ship coming from Mauritius laden with Indian mangoes, cinnamon and other exotics that included the euphonious bilimbi, brindonne and carambola, as well as jackfruit and June plum. Eighteenth-century botanizing had become a global enterprise, undertaken by colonial powers such as France, Spain and the Netherlands as well as Britain, to establish encyclopedic plant collections for study and sometimes useful propagation. While most specimens gathered by British collectors were destined for the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, outside London, some went to satellite stations at Calcutta, Sydney, St. Vincent and to Bath.

And it was in homage to the second, transforming consignment of plants brought to Bath that I now paid my visit, for Bath Gardens played a small but poignant part in one of the great sea sagas of all time—the mutiny on the Bounty. As the world well knows, in the year 1789, Lt. William Bligh lost his ship Bounty at the hands of one Fletcher Christian and a handful of miscreants on a voyage back to England from Tahiti, where the Bounty had been sent to collect breadfruit and other useful plants of the South Pacific. The breadfruit expedition, backed by the great and influential botanist Sir Joseph Banks, patron of Kew Gardens and president of the Royal Society, had been commissioned to transport the nutritious, fast-growing fruit to the West Indies for propagation as a cheap food for slave laborers who worked the vast sugar estates. The mutiny, therefore, not only deprived Bligh of his ship, but defused a grand botanical enterprise. Dumped into a lifeboat with 18 members of his crew, and with food sufficient for a week, Bligh navigated through high seas and perilous storms over a period of 48 starving days, drawing on his memory of the few charts he had seen of the mostly uncharted waters. His completion of the 3,618-mile voyage to safety in Timor is still regarded as perhaps the most outstanding feat of seamanship and navigation ever conducted in a small boat. As a token of its esteem and trust, the British Admiralty had promoted the young Lieutenant Bligh to captain—and packed him off on another two-year mission, back to Tahiti for the infernal breadfruit. Two thousand one hundred twenty-six breadfruit plants were carried from Tahiti, in pots and tubs stored both on deck and in the below-deck nursery. The expedition's gardener described depredations inflicted by "exceedingly troublesome" flies, cold, "unwholesomeness of Sea Air," salt spray and rationed water; nonetheless, 678 survived to the West Indies, being delivered first to St. Vincent and finally to Jamaica. And it was in February 1793 that Capt. William Bligh, fulfilling at last his momentous commission, had overseen his first deposition of 66 breadfruit specimens from Tahiti, all "in the finest order," in Bath Botanical Gardens.

"The Botanic Garden had no rare things in it, except the Sago Plant, the Camphor and Cinnamon," Bligh noted in his log with palpable satisfaction; Bath's meager holdings would only enhance the value of his own, which included more than 30 species in addition to the breadfruit—the carambee, which Malays used for perfume, and the mattee and ettow, which "Produce the fine red dye of Otaheite."

Bligh's ship Providence had arrived at Port Royal, Kingston, to some fanfare, its "floating forest," according to an officer of the ship, "eagerly visited by numbers of every rank and degree"— so much so that, as another officer complained, "the common Civility of going around the Ship with them and explaining the Plants became by its frequency rather troublesome." Leaving Kingston, Bligh had sailed for Port Morant, Bath's harbor. Here, the day after his arrival, with moderate temperatures in the 70s and a fine breeze blowing, the Providence had been emptied of its last 346 plants, which were carried six miles overland on the heads of bearers and deposited in a shady plot in these gardens.

Today, a cluster of breadfruit trees still flourishes, demure on the edge of dark shade by the western wall. As most breadfruit reproduce not by seed but by sending out long suckers, the modern specimens are affectionately presumed to be "daughter" trees of Bligh's transports. Andreas Oberli, who has aggressively agitated for the restoration of the island's historic gardens, regarded them critically. "You see, this one is from Timor—it has a totally different leaf than the others." The glory of the "classic" Tahitian breadfruit is its large, ornamentally lobed, glossy green foliage. "They should get the labels right," he said curtly, Bligh-like in his keen attention to botanical duty.

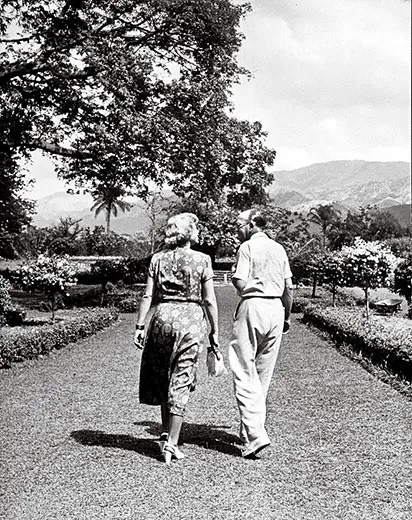

Under the towering shade of the oldest trees, a young couple strolled reading the labels of each. Two little boys stood looking intently into a Chinese soapberry, incriminating slingshots in their hands. "Not while I'm here, OK?" Andreas growled, and the boys shrugged and wandered off. Three enormous women entered the garden and, spreading blankets on the grass, arrayed themselves massively along the earth. Andreas and I picnicked under the shade of a cannonball tree, the high rustling of the garden's glinting fronds and foliage masking most other sounds. Birds, buffeted but triumphant, rode the wind. On the ground, unmolested and untroubled, a rooster strode among the shadows in conscious magnificence, his comb, backlit by the lowering sun, glowing red. "A survey was taken at Kew some years ago," said Andreas; "only 16 percent of the people who visited were there to see the plants." We looked around. "They came for the garden."

My interest in the botanical gardens of Jamaica arose mainly from their little-known role in the saga of Bligh and the mutiny on the Bounty, which I had researched for a book. There was also a personal incentive. I had briefly lived in Jamaica as a child, and one of my earliest true memories is of the parklike Hope Royal Botanical Gardens, in Kingston. In my memory, I see a tunnel of climbing vines with trumpety orange flowers; there had been a bandstand and beds of flowers you could touch. But I had not traveled inland, nor had I seen—and until my Bounty studies, even heard of—Jamaica's other historic gardens.

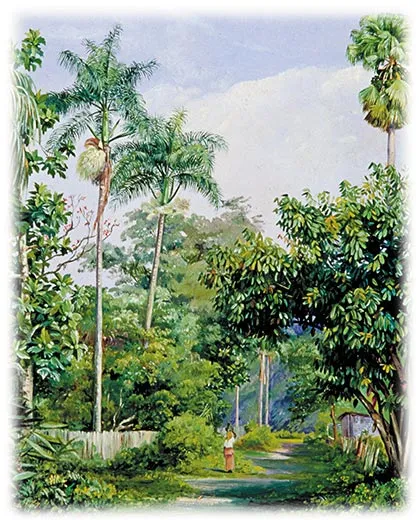

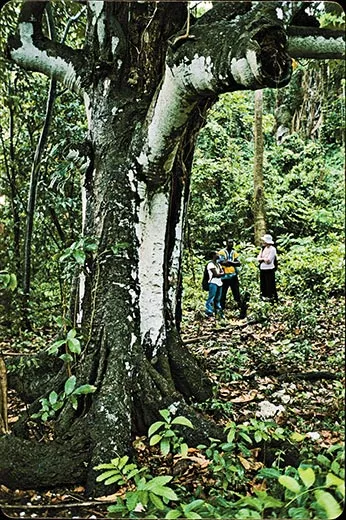

All of Jamaica, it has been said, is a botanical garden. Inland, the mountain clefts and gullies, often coursed by streams, are tangled with greenery, the trees woolly and blurred with epiphytes, ferns, orchids and the night-scented, night-blooming cereus. An island with a total area of less than 4,000 square miles, Jamaica has 579 species of ferns alone, a higher density, it is believed, than anywhere else in the world. Epiphytes dangle from telephone wires; the forests are hung with flowering vines; often on this trip I thought of how Bligh and the men of the Providence must have been reminded here of the lush blue-green landscape of Tahiti.

But the emphasis on a botanical garden in particular is significant. Existing for study, experimentation and display, a botanical garden is encyclopedic, learnedly diverse, replete with exotic specimens. It is a stunning fact that in the natural garden of Jamaica, the majority of the island's defining plants were imported and disseminated by botanical ventures like those conducted by William Bligh. Few of Jamaica's important economic plants—cassava, pineapple, cedar, mahogany and pimento—are native, and most of the island's defining flora is exotic. In the 16th century, the Spanish brought in sugar cane, bananas and plantains, limes, oranges, ginger, coffee and a variety of European vegetables. The British, driving out the Spanish in 1655, were responsible for the mango, which by 1793, as Bligh noted, grew "luxuriantly, and...are plentifull all over the Island." Similarly, the glossy, red, pear-shaped ackee, poisonous if eaten unripe, and today the national food of Jamaica, came from West Africa, brought either by European slaver or African slave.

For it was not, of course, only Jamaica's flora that was imported. When Columbus first reached Jamaica in 1494, the island had been inhabited by the Taino, a northern Caribbean people. The first Africans arrived shortly thereafter, in 1513, as servants, herdsmen and cowboys, as well as slaves to the Spanish. Under British rule, slaves were imported in ever-increasing numbers to do the brutal work in the cane fields of the great sugar estates. Most, including the Comorantee, Mandingo, Ashanti and Yoruba, came from West Africa, but thousands of bondsmen, slaves in all but name, came from Ireland, where Oliver Cromwell was intent on the extermination of the Irish people; some speculate that the characteristic lilt in Jamaican speech comes from the Irish, not the English. Today, Jamaica's population of just under three million is descended from its many transplanted peoples—West African slaves; Irish, Scottish and Welsh bondsmen and servants; British soldiers; Chinese, Indian and Lebanese merchants; and English landowners. The native Taino, who virtually disappeared as a people within 30 years of the arrival of the Spanish, are today encountered only in relics of their language, in words such as "hammock" and "canoe," and the island's name—Hamaika, the "land of wood and water."

Jamaica has also attracted a striking number of accidental transplants, random wanderers, who, like the buoyant fruit of the Barringtonia, drifted ashore and took root. Such a transplant was Andreas Oberli, who came to Jamaica in 1978 and eventually stayed on. "This was after Allen and before Gilbert," he said, locating events in the Jamaican way, by their relationship to landmark hurricanes.

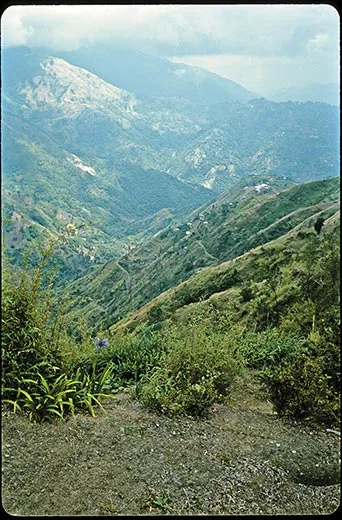

We were again navigating traffic out of Kingston, headed for another historic garden. Kingston's setting, between its magnificent natural harbor (the largest in the Caribbean) and the Blue Mountain foothills, should make it one of the most striking cities in the world; but even in this season of violent bougainvillea bloom, the traffic and sprawl overwhelm, and most visitors look wistfully to the hills, where we were headed. Now, on the narrow road that winds along the Hope River valley, we found ourselves navigating pedestrians, veering cars and goats. "Never in Jamaica has a car hit a goat," Andreas declared defiantly, as goats and their kids skipped and grazed along the precipitous roadsides. Shortly before the paved road ran out, he stopped again to point to the ridgeline above us, darkly profiled against the clouded white sky. A tree with a tufted crown, like a bottlebrush, could just, with guidance, be discerned. "Cinchona," he said.

Half an hour later, our four-wheel drive jeep lurched into the garden. Here, at the top of the island, the white sky settled determinedly upon us. Sometimes in sharp, dark silhouette, sometimes misted indistinctly, towering trees breasted the pressing clouds that trickled in white drifts and threads from where they boiled out of the valley. Andreas looked about him, pleased; things were in not-bad order. The grass was clipped and green with cloud dew; the raised brick beds, filled with old favorites—begonias, geraniums, masses of daylilies—were all well tended. The beds he had built himself, between 1982 and 1986, when he had been superintendent of the garden.

"The big trees were lost to the hurricanes," Andreas said. He had begun his duties in the wake of Allen (which hit in 1980) with the aid of two Peace Corps workers who had been assigned to him. "For the first year, we did nothing but drag and clear trees; we cut up or felled between two to three hundred." The debris gone, he had turned to reclaiming the garden. A ramshackle bungalow, dating from the first years of the garden's creation, had survived Allen, and on the grassy platform before it Andreas had laid the beds and fishpond, before moving down the slopes to more naturalistic plantings—the green stream of moss with its banks of polished bamboo, the azalea walk and avenue of ferns, the blue hill slope of agapanthus.

The origins of Cinchona Gardens lay in the abandonment of the garden at Bath, which had suffered from frequent severe floodings of the nearby Sulphur River, as well as its inconvenient distance from Kingston. Consequently, in 1862, the Jamaican colonial government established a new botanical garden at Castleton, some 20 miles north of Kingston, a decision that seems also to have inspired the afterthought of the Hill Gardens, as Cinchona was also known, which at nearly 5,000 feet is the highest in Jamaica. Originally, its generous allotment of 600 acres had been envisioned as a plantation of "Peruvian bark," or cinchona trees, from which the anti-malarial drug quinine is made. When the East Indian industry usurped the quinine market, plans for Cinchona shifted to the cultivation of temperate tropical plants; among other things, English planters had long harbored the hope of cultivating those necessities of life fondly associated with Home, such as the potato and the almighty cabbage, which, in this land of tropical abundance, were still found wanting.

"Up here, we have European weeds," said Andreas, and pointed out the clover, dandelions and daisies that spangled the grass around the ruined station house. "A lot of stones were imported for building, such as sandstone and Carrara marble; they were shipped covered with hay that was afterwards fed to horses. The seed in their manure did not germinate in the lowlands, but they do well up here in this European climate."

At the edge of the mountain, the clouds briefly dissolved to reveal the green, sunlit valley, combed with small farming plots; then the mist closed in again, effacing the sky entirely, and it began to rain. The old station house, shown in photographs in the 1920s and 1930s as a trim little bungalow, hulked ruinously and uselessly behind us, offering no shelter, and we tramped wetly through the garden, past the Japanese cedar conifers (Cryptomeria) and the Lost World avenue of ferns.

Out of the dripping mist loomed a piratical figure, black of beard and with a stumping gait, who, although his face remained inscrutable, in the country way, greeted Andreas warmly. Glen Parke had worked with Andreas during his superintendence in the 1980s. Living in the nearby village of Westphalia, he was still employed as a gardener by the Ministry of Agriculture. The clipped lawn and weeded beds were partly his work, carefully maintained far from admiring eyes. He and Andreas embarked upon a short tour of old friends, remarking on a tender cinchona sapling that stood where there should have been a tree. "Yah, we lose him," said Glen sadly, of the sapling's predecessor.

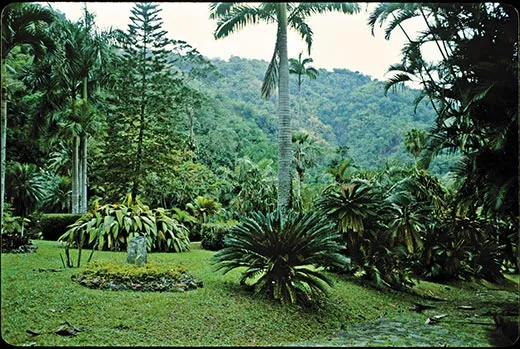

Each of Jamaica's four great gardens, although established along similar principles, has acquired its own distinctive aura. Hope Gardens, in the heart of Kingston, evokes postcard pictures from the 1950s of public parks, gracious and vaguely suburban and filled with familiar favorites—lantana and marigolds—as well as exotics. Bath has retained its Old World character; it is the easiest to conjure as it must have looked in Bligh's time. Cinchona of the clouds is otherworldly. And Castleton, the garden established to replace Bath, fleetingly evokes that golden age of Jamaican tourism, when visitors arrived in their own yachts—the era of Ian Fleming and Noel Coward, before commercial air travel unloaded ordinary mortals all over the island.

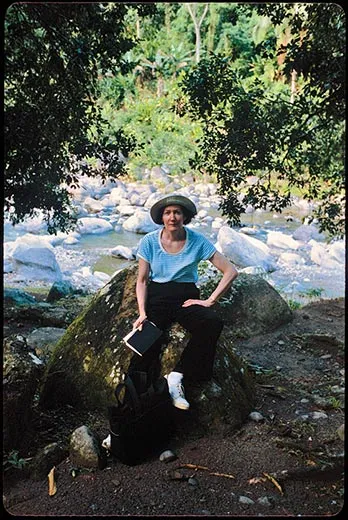

A showcase of terraced, tropical glamour, Castleton is dotted with ornamental ponds, wound through by artful, cobbled pathways that lead hither and yon beneath the canopies of its famous palms and its streamers of dangling orchids. Unlike Jamaica's other gardens, Castleton's star has never dimmed, perhaps because, straddling the direct road from Kingston to Ocho Rios, it has been accessible and in plain sight. Many Jamaicans recall family picnics taken beside its river, whose palest turquoise water delineates the garden's eastern boundary. Today, Castleton is a featured stop for tourists; on this day, the roadside parking lot was full, and local guides possessed of uncertain knowledge were conducting impromptu tours.

Across the river a cliff wall loomed, hung with its own flowering vines, lanced with its own straight-backed palms straining for light. Jamaica's own flora had been of great interest to Bligh's patron, Sir Joseph Banks, and Bligh's instructions directed that after disposing of his Tahitian cargo he was to take on board a consignment of Jamaican specimens, potted in readiness by the island's chief botanists.

"I find that no Plants were as yet collected for His Majestys [sic] Garden at Kew," Bligh recorded in his log on February 13, 1793, the understated entry bristling with irritation at this failure of duty. Bligh's health had not recovered from his ordeal following the loss of the Bounty, now four years past, and he was wracked with recurrent malaria he had caught in the Dutch East Indies. Indeed, early in this second voyage, Bligh's officers had feared for their captain's life; but he had rallied, as always, and with head pounding, suffering savagely from sun glare under the Pacific skies, he had returned to Tahiti, overseen the transplantation of 2,634 plants, conned his ships through the treacherous Endeavour Straits and arrived in Jamaica. Now, at this final stage of his long and arduous passage, delays mounted and Bligh's health again faltered. The late-arriving Jamaican plants destined for Kew were eventually stowed on board the Providence, then unloaded, as word came from the Admiralty that because of events in France—the guillotining of Louis XVI and subsequent war with England—British ships, the Providence included, should stand by for possible action.

It was early June when Bligh at last received orders to sail. The Providence, stowed with 876 carefully potted Jamaican specimens, weighed anchor at Port Royal, and struck west for Bluefields Bay. Here, Bligh intended to rejoin his tender, the Assistant, which had been earlier dispatched with 84 breadfruit, along with four mysterious "Mango-doodles," for estates at this opposite end of the island. Bluefields had assumed a place of some importance in my own botanical pilgrimage; not only was this the site of Bligh's final anchorage in Jamaican waters, but, so it was rumored, inland from the bay, two of Bligh's original breadfruit trees survived.

Although old Jamaican hands pronounce Bluefields "ruined," to a first-time visitor it appears as one of the more unspoiled stretches of Jamaica's coastline. In living memory, floods and hurricanes have silted and altered the shoreline—Ivan, in 2004, caused memorable damage—and the beach, it is true, is scant, wedged between narrow stretches of mangroves that parallel the coastal road. A string of bright fishing boats lay beached, and opposite some desolate food stalls a wooden jetty extended into the now flat-calm sea.

I had arranged to meet with a professional guide of the ambiguously named Reliable Adventures Jamaica. Wolde Kristos led many ventures in the area—nature tours, bird-watching tours, tours of Taino, Spanish and English history—and was an ardent promoter of Bluefields as the tourist destination best representing "the real Jamaica." He knew the fabled breadfruit trees well, as his foster mother, born in 1912, had told him, "All senior citizens in Bluefields tell of William Bligh," Wolde said.

I had obtained rough directions to one of the trees: "Near bend in the road where you would go up to Gosse's house"—"Gosse" was Philip Henry Gosse, who in 1844-45 had stayed at an old "Great House," or former plantation house, while he researched and wrote his classic book The Birds of Jamaica.

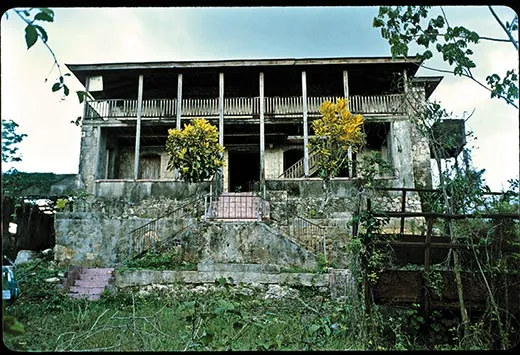

The Great House stood, semi-derelict, at the end of a grassy drive in an overgrown yard. A mother goat and her kid had taken shelter from new rain under the porch, whose supportive timbers had been replaced by twin concrete columns. The exuberant Wolde, with his associate, Deceita Turner, led the way decisively up the front steps and pounded on the locked door. "We will get the caretaker," he said. At length the door was opened by an attractive young woman, who greeted us politely and allowed us in to view the house's historic interior—its mahogany stairway and arches, the old flooring and a hallway of tightly shut mahogany doors.

"They are afraid I would rent the rooms," said the caretaker, explaining why every interior door to every room was locked, except the one to the room in which she slept; "they" were the absent owners, an Indian family who now lives in England. "I saw them about two years ago," she mused. She was paid no salary but was allowed to live here and to cook her meals outside. "She is guarding this place with her life!" said Wolde in sudden passion. "If she were not here, people would not move into the house, but they would cut down the trees—cedar is expensive."

One of Bligh's fabled breadfruit trees had allegedly stood in the grassy yard, until it had been felled by Ivan. A stump and rubble of wood still marked the site. Behind it, at a plausible distance among some undergrowth, was a sturdy breadfruit sapling, several feet high, which Wolde speculated was a sucker of the old original.

The breadfruit tree that still survived stood just around the corner, off the road from Bluefields Bay, in a grassy lot in which a battered bus was parked. The long rain at last stopped, and now, in the last hour of daylight, this little patch of secondary forest glittered greenly.

Rising to a magnificent 100 feet, the tree stood at the foot of a small gully, backed by a vine-covered embankment. A mottled white bark covered its six-foot girth, and the wide ground stretching beneath its broad canopy was littered with lobed leaves and fallen fruit. Wolde pointed to the gully wall. "This is what protected it from Ivan."

On June 11, 1793, Bligh had overseen the Providence washed "fore and aft and dried with Fires." He had spent the week off Bluefields readying his ship—overseeing the land parties that scavenged for timber or filled water casks from the Black River—and exercising the ship guns. Twice he gave the signal to sail, and twice the "constant Calms and light Variable Airs" prevented him from doing so.

The passage from Jamaica to England was one that Bligh, the consummate navigator, could surely have accomplished in his sleep. He knew this particular route well, for from 1784 to 1787, before his fateful commission on the Bounty, Bligh had lived in Jamaica, employed by his wealthy uncle-in-law Duncan Campbell to sail merchant ships loaded with rum and sugar between Jamaica and England; Lloyds List, a registry of shipping movements, records ten such voyages made by Bligh during this time. Remnants of the Salt Spring estate, the Campbell property that had been Bligh's base when he was not on his ship, lie on Green Island Harbor less than 20 miles from Lucea, the attractive old 18th-century town; the earliest known chart made by William Bligh is of the Lucea Harbor.

At the old British fort, its black guns still trained on the sea, I met with Evangeline Clare, who had established the local historical museum and has long conducted research of her own into the sprawling and powerful Campbell clan; it was she who had supplied me with the Lloyds shipping lists. A striking African-American woman with silver-blond hair, she had come to Jamaica 44 years ago as a Peace Corps volunteer, married a Jamaican and stayed on.

In the heat of the day, we drove the short distance from her house on Green Island down a dirt track to the site of Campbell Great House, which, built in the 1780s, was slipping brokenly into scrub. "Cane cutters have been camping here," Evangeline told me, and was clearly concerned about the reception we might meet; but in fact the ruined house, which wore an air of ineluctable abandonment, was deserted. It had lost its roof to Gilbert, but its thick, immutable walls, built of ballast stone carried from England, still held off the heat. The Campbell garden had been legendary, "with beautiful lawns, groves, and shrubberies," as a contemporary visitor glowingly reported, "which give his residence the appearance of one of those charming seats that beautify the country, and exalt the taste of England." In particular, Mr. Campbell had been assiduous in his cultivation of the breadfruit, which had continued to flourish around the house over the passing centuries, and were cut down only in recent years.

Beyond the house stretched the remnant cane fields, the basis of Jamaica's enormous wealth during the 17th and 18th centuries, when it was the world's leading producer of sugar, molasses and rum, and one of Britain's most valuable possessions. This heady run as the center of the economic world had ended with the end of slavery in the 19th century.

"Somewhere along the line, I think people figured out that if they could just get rid of this cane, they could do away with the whole slave thing," said Evangeline. "I mean—can you imagine..."

By 1793, when the Providence at last delivered its Tahitian transplants, the days of the slave trade were already numbered. The sentiment of ordinary Englishmen, long opposed to the practice, was being felt in their boycott of West Indian products. While Bligh's own views regarding this institution are not known, the official view of his commission was enshrined in the name of his first ship; when purchased by the Admiralty from Duncan Campbell it had been named Bethia, but was rechristened for its fateful mission—Bounty. Although the breadfruit tree flourished and spread across Jamaica, more than 40 years passed before its fruit was popular to local taste, by which time, in 1834, emancipation had been declared in the British Empire.

Today, the breadfruit is a favorite staple of the Jamaican diet. A mature tree produces in excess of 200 pounds of fruit a season. One hundred grams of roasted breadfruit contains 160 calories, two grams of protein, 37 grams of carbohydrates, as well as calcium and other minerals. Breadfruit is eaten roasted, grilled, fried, steamed, boiled and buttered, and as chips and fritters; over-ripe, the liquid fruit can be poured out of its skin to make pancakes, and mashed with sugar and spices it makes a pudding. For its longevity and self-propagation it is perceived as a symbol of perseverance, a belief, according to the Encyclopedia of Jamaican Heritage, "encoded in the saying, ‘The more you chop breadfruit root, the more it spring.'"

Its indelible association with William Bligh, then, is appropriate, for he had persevered through two momentously arduous voyages to fulfill his commission. Other ordeals were to come; back in England, families of the mutineers had been spinning their own version of the piratical seizure of the Bounty, recasting Bligh, who had departed England a national hero, as a tyrannical villain. Weighing anchor in Bluefields Bay, Bligh had no premonition of the trials ahead; he was mindful only of what he had accomplished. "[T]his was the quietest and happiest day I had seen the Voyage," he wrote, as a private aside, in his log, on the day he discharged his plant cargo at Bath. He had done his duty and believed that all that remained was to sail home.

Caroline Alexander wrote The Bounty and the forthcoming The War That Killed Achilles. George Butler's films include Pumping Iron and other documentaries.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.