Check Out These 10 Must-See Fall Exhibits

Underwater artifacts and Winnie the Pooh take center stage at these new museum exhibits this fall

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/2b/572beb52-2047-42be-95bc-9a88c0109a14/ext_201804020023.jpg)

Get out and make fall a season of learning across the United States. These 10 museums will teach you, among other things, about the history of Victorian dolls, the gravity of Bill Traylor’s art and the mysteries of ancient Egypt.

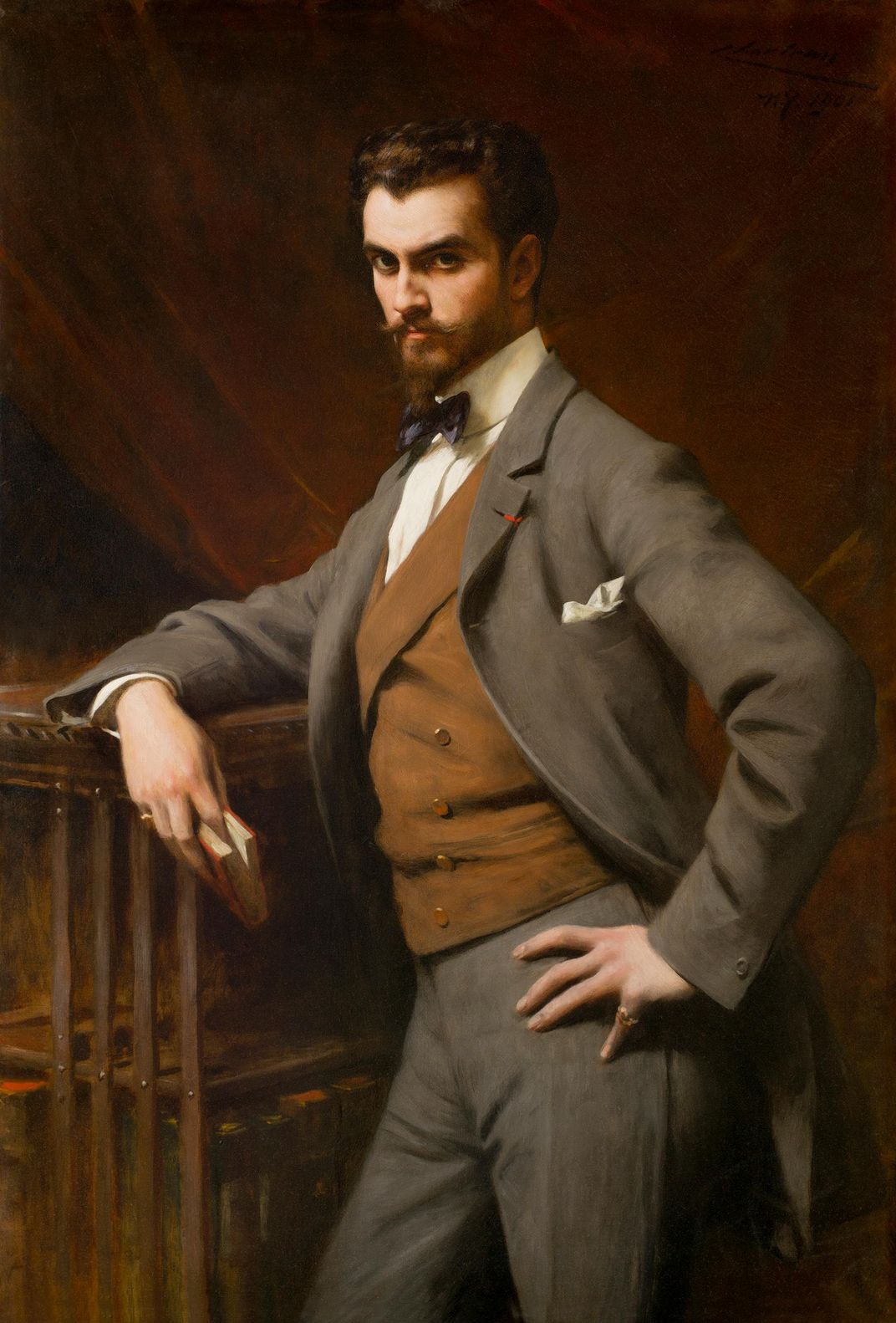

The Driehaus Museum—Beauty’s Legacy: Gilded Age Portraits in America

(Chicago, Illinois; September 8, 2018 – January 6, 2019)

The Driehaus Museum’s flagship fall exhibit is a collaboration with the New-York Historical Society that focuses on formal portraiture in the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Beauty’s Legacy showcases about 60 portraits of the wealthy and elite, who wished to show off their social status by commissioning famous artists to paint their likeness. Families like the Vanderbilts, the Astors and the Bonapartes are featured in portraits painted by artists like Rembrandt Peale, Eastman Johnson and John Singer Sargent. In addition to Beauty’s Legacy, the Driehaus will concurrently run Gilded Chicago: Portraits of an Era and Treasures from the White City: The Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Both tell a story of post-fire Chicago and how it reemerged as a major metropolitan city. Gilded Chicago has ten portraits in the collection of familiar Chicago names like Pullman, Field and McCormick.

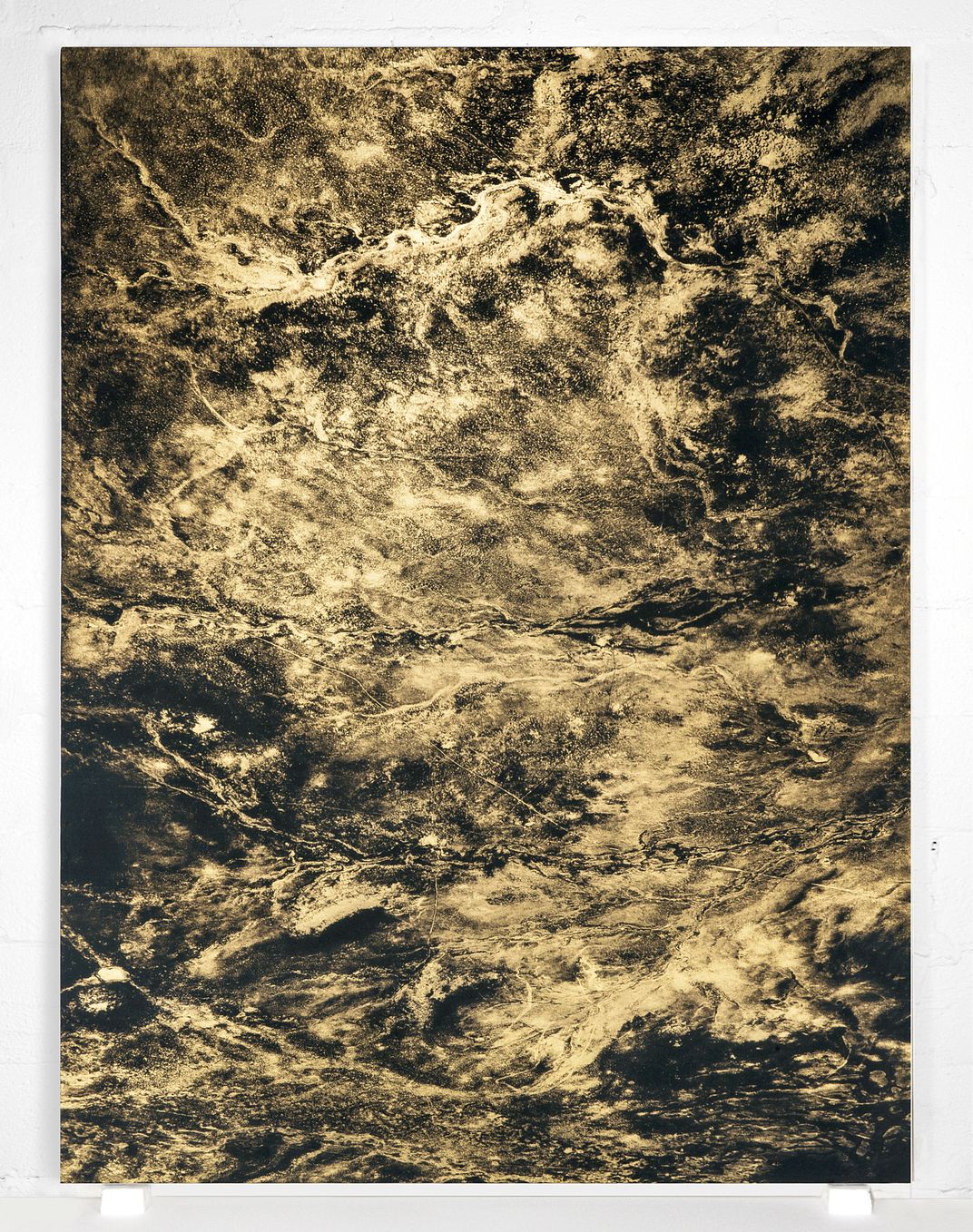

Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and USC Fisher Museum of Art—Justin Brice Guariglia Earth Works: Mapping the Anthropocene

(Los Angeles, California; September 18, 2018 – December 8, 2018)

Starting September 18, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (NHMLA) and its neighbor museum, the USC Fisher Museum of Art, will display a joint exhibition focusing on the Anthropocene, which is the geologic age of human impact on the planet and on climate change. Earth Works features 24 pieces from artist Justin Brice Guariglia, who flew with NASA to study melting glaciers in Greenland. Twenty-three pieces will be on display at the USC Fisher Museum, showcasing photos the artist took on his NASA trips through a special acrylic printing process that blends photography and painting. The NHMLA will display Guariglia’s large-form piece Jakobshavn I, measuring 11 feet by 16 feet. It depicts one of the fastest melting glaciers in Greenland.

South Carolina Historical Society Museum—Fireproof Building

(Charleston, South Carolina; Opens September 22)

After a multi-million dollar renovation, one of South Carolina’s oldest buildings, the Fireproof Building, will reopen in September as an interactive museum documenting more than 30 years of the state’s history. The exhibits will be shown through the eyes of historical South Carolina residents, and will also highlight exciting pieces from the South Carolina Historical Society’s collection. Some must-see pieces include rice plantation maps from the 1700s (which are currently on loan from the Smithsonian), Revolutionary War officer Francis Marion’s powder horn and pipe bowls from the 1700s. Visitors will also enjoy interactive map tables and active portraits of four local historical figures.

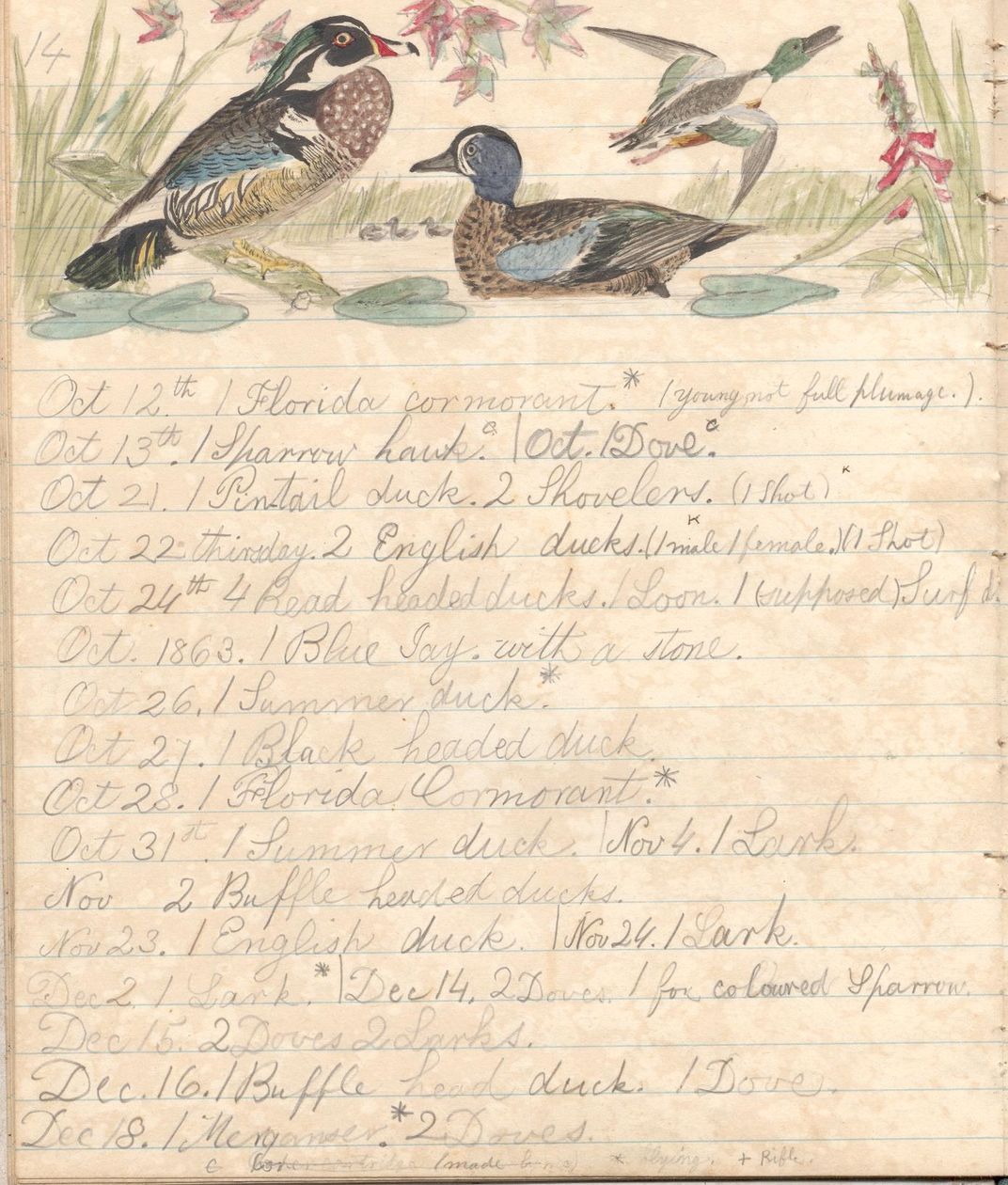

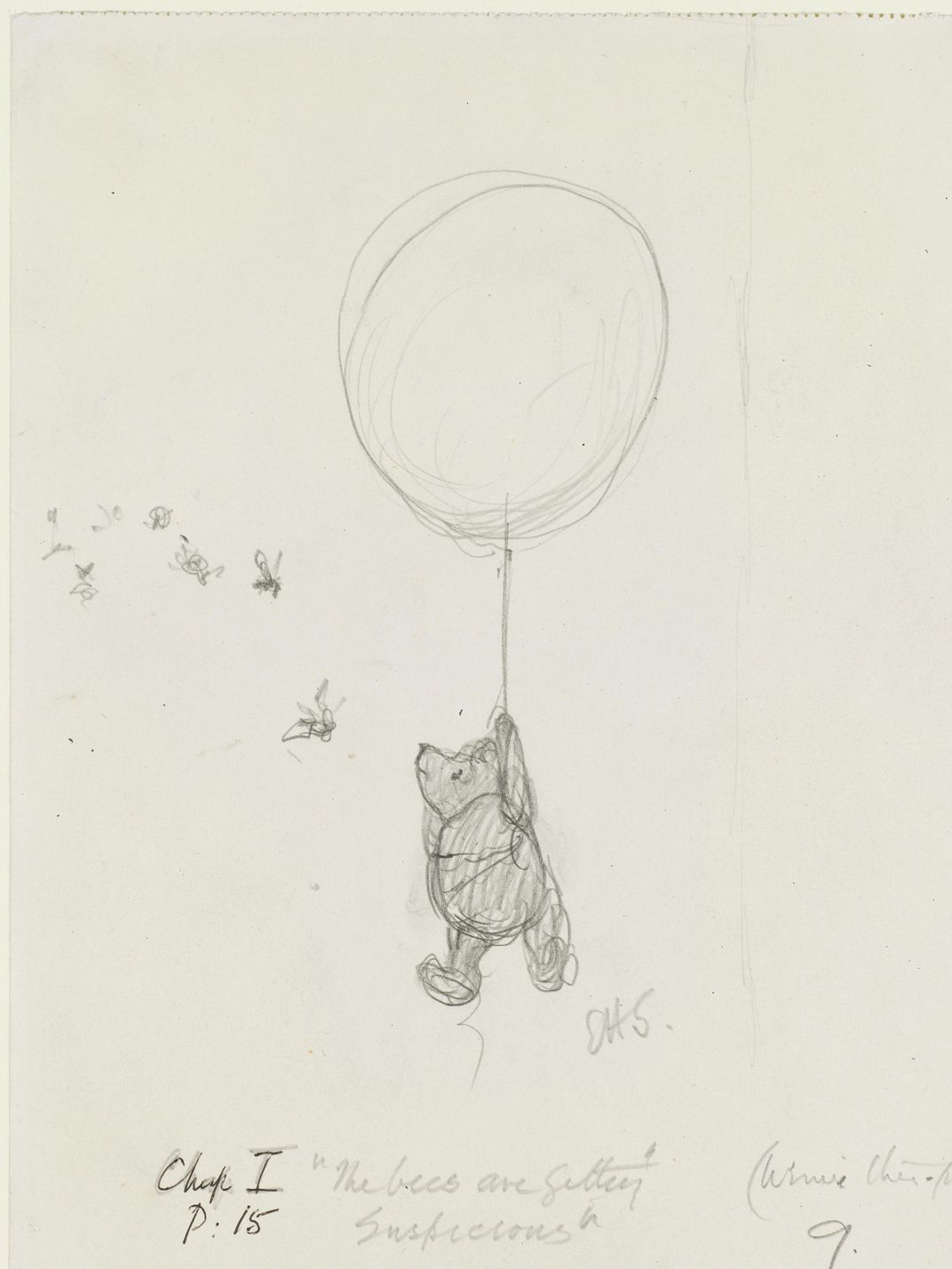

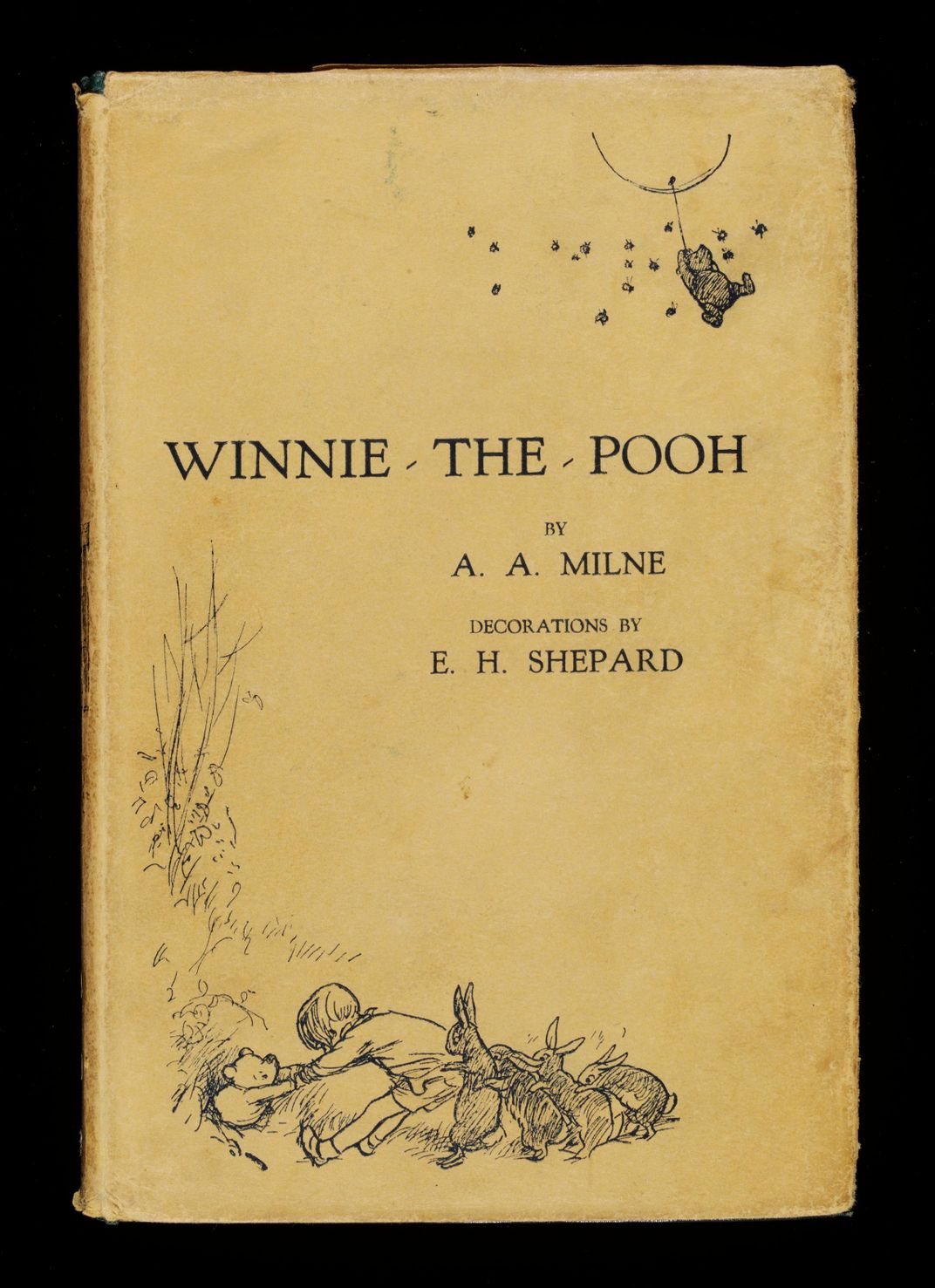

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—Winnie-the-Pooh: Exploring a Classic

(Boston, Massachusetts; September 22, 2018 – January 6, 2019)

Fans of Winnie the Pooh will love the Exploring a Classic exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston—it’s designed to follow the history and appeal of the classic stories from inkling to literary powerhouse. The exhibit will showcase about 200 artifacts from A. A. Milne and E. H. Shepard, including original drawings, early editions, photographs and letters showing the creation tales of all the characters of the 100 Acre Wood, and how they’ve stood the test of time, becoming childhood favorites for generations. Don’t miss the original line drawings of Pooh and Christopher Robin, the teddy bear that inspired it all, plus a set of modern sake cups.

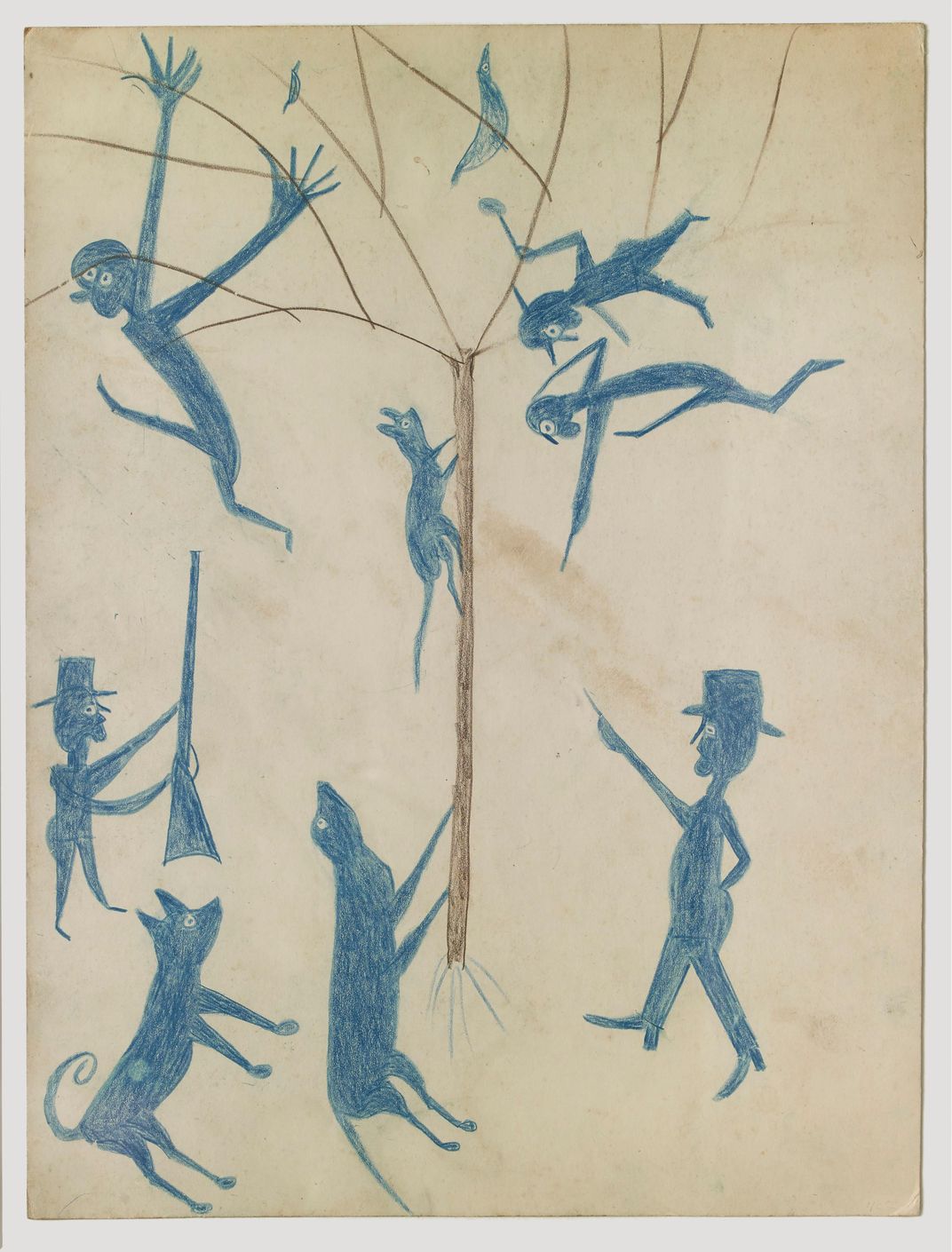

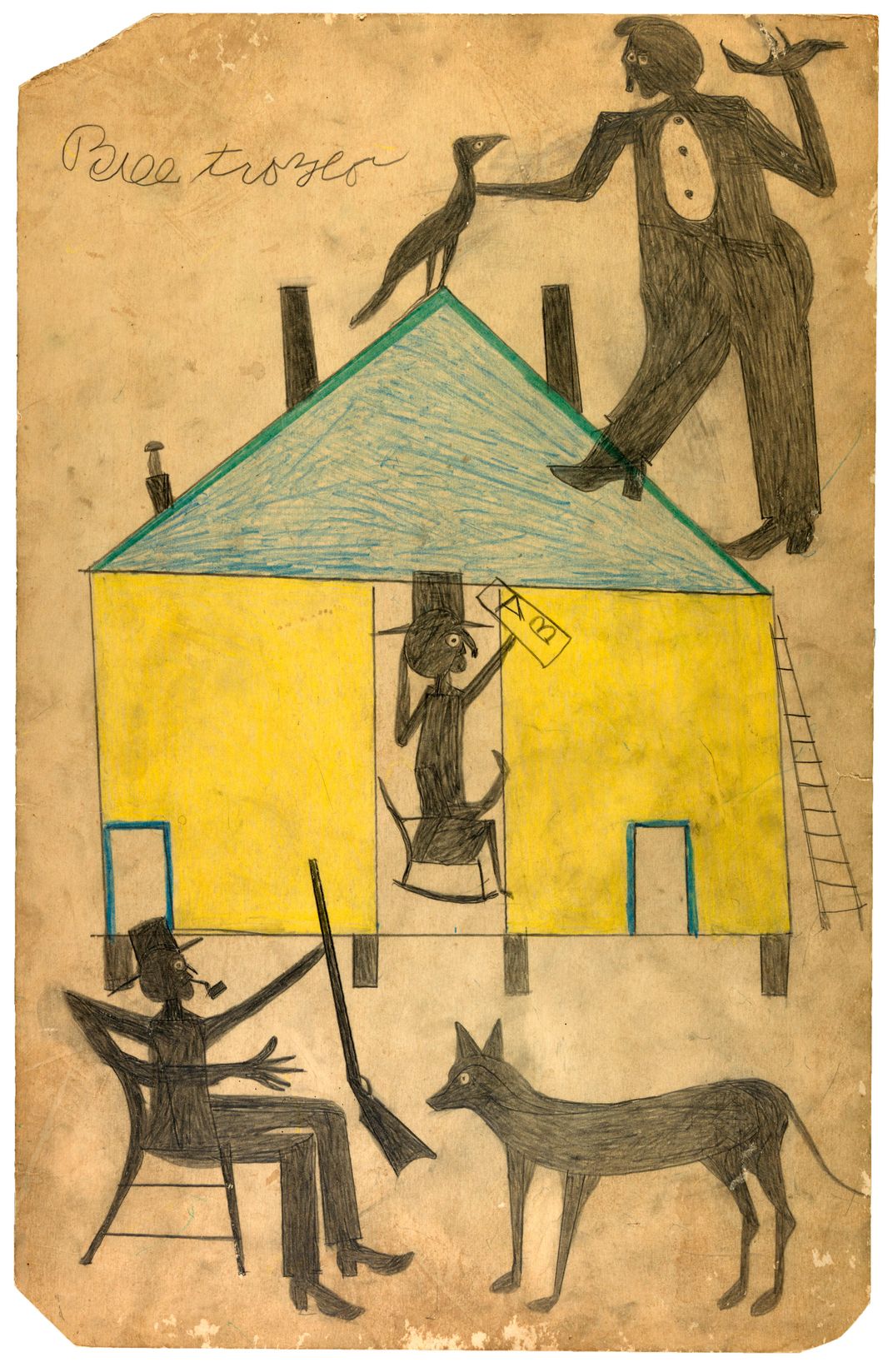

Smithsonian American Art Museum—Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor

(Washington, D.C.; September 28, 2018 – March 17, 2019)

Exclusive to the Smithsonian American Art Museum this fall is an exhibit about the collected works of Bill Traylor, the only known artist enslaved at birth to produce a large body of drawn and painted works. Between Worlds will feature 155 pieces of Traylor’s work. He began creating his art in 1939 when he was in his late 80s. At that time, he lived on the streets in Montgomery, Alabama, where he was born into slavery. Although he only lived for ten more years, he left behind more than a thousand pieces of art. His simple but colorful drawings and paintings show the juxtaposition of white and black cultures at the time and the political tones of the time.

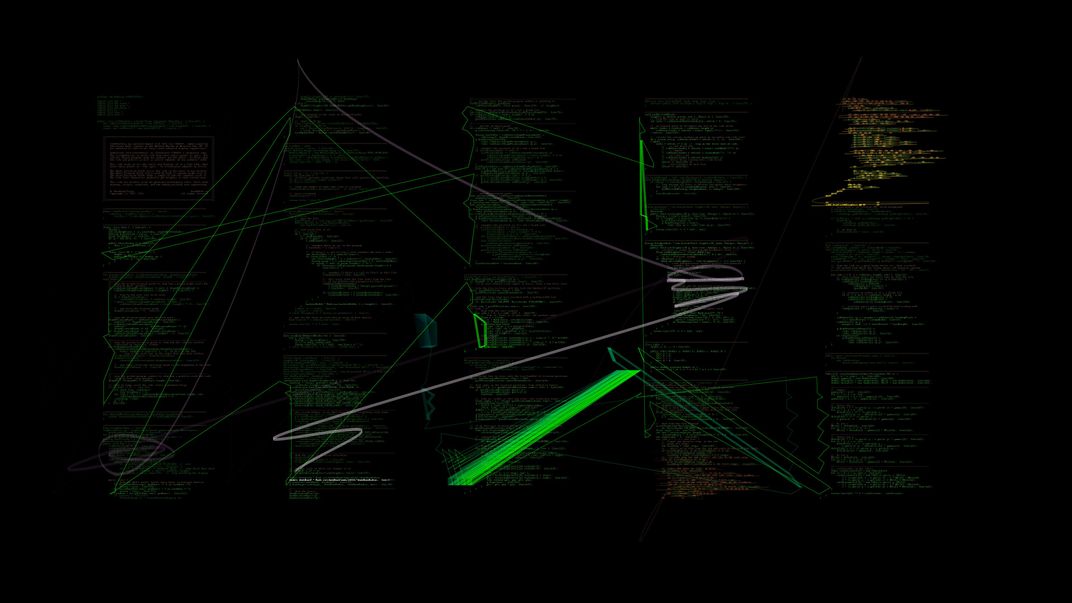

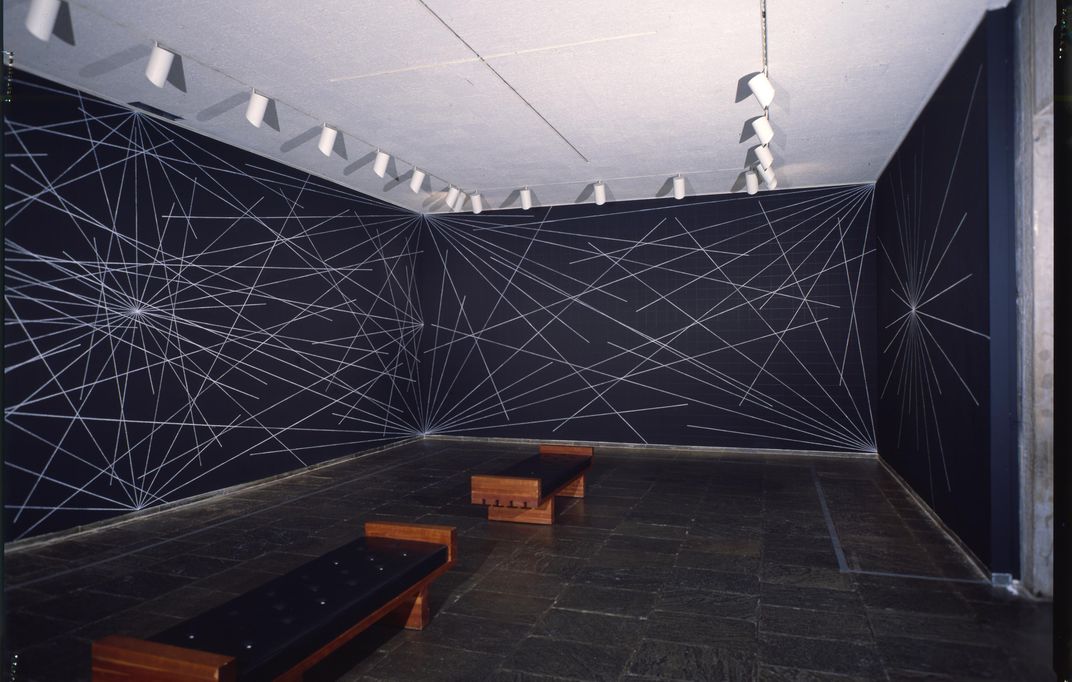

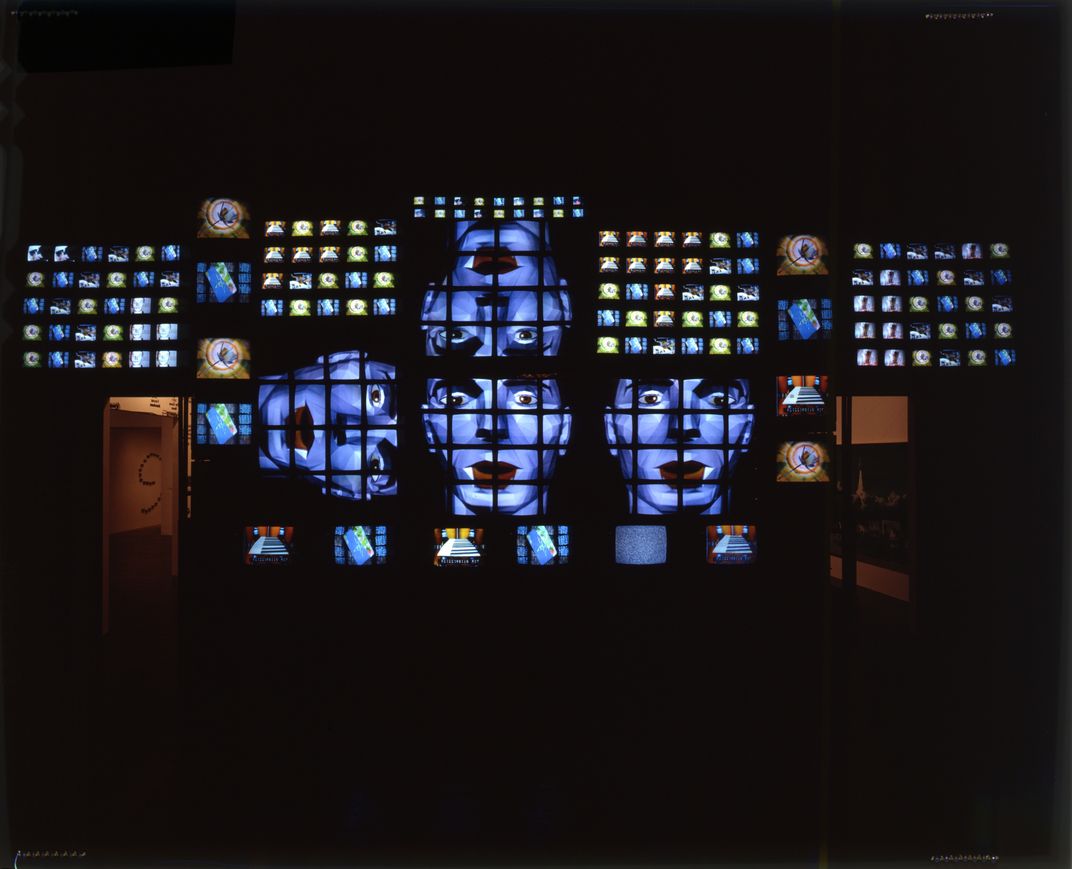

Whitney Museum of American Art—Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018

(New York, New York; September 28, 2018 – April 14, 2018)

Computer programming takes an artistic turn in Programmed, a new exhibit at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The exhibit explores art made between 1965 and 2018, all following a specific set of programmed instructions, rules, algorithms and codes. Programmed follows two distinct threads—one showing how programming can impact and change conceptual art, and the other showing how algorithms and instructions can manipulate what we see on television or through other image signals. The exhibit uses the Whitney’s own collection to explore how computational art has evolved and changed over the decades based on technology.

Wrightwood 659—Ando and Le Corbusier: Master of Architecture

(Chicago, Illinois; October 12, 2018 – December 15, 2018)

Hiding in a Chicago neighborhood, in what looks like just another apartment building, is a new exhibition space celebrating architecture and socially engaged art. Wrightwood 659 was once a three-floor walkup on the city’s north side but is now a four-floor space with an outdoor patio on the top floor. The inaugural exhibit will be Ando and Le Corbusier: Masters of Architecture, opening in October. Tadao Ando is a Pritzker Laureate and designed the entire space. The exhibit will highlight Swiss architect Le Corbusier’s influence on Ando and his work. More than 100 Le Corbusier models, archival images and drawings will be on display, plus 106 small-scale models that Ando’s students made of Le Corbusier’s work. Ando’s work will be on display on the third and fourth floors of the space. Some must-sees include Le Corbusier’s 1929 model of the Villa Savoye, a 1950 model of the chapel at Ronchamp and Ando’s students’ 60-foot-long art island model of Naoshima. Wrightwood 659 will host two ticketed exhibits a year, alternating between architecture and social activism focuses. Tickets must be reserved online.

Minneapolis Institute of Art—Egypt’s Sunken Cities

(Minneapolis, Minnesota; November 4, 2018 – April 14, 2018)

More than 1,200 years in the past, the Egyptian cities of Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus became victims of the planet, submerged in the Mediterranean Sea’s rising tides. They stayed hidden for more than a millennium, until 2000, when underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio rediscovered them in Aboukir Bay near Alexandria. Goddio and his team found a treasure trove of ancient Egyptian artifacts, everything from statues and jewelry to ceramics and religious icons. Egypt’s Sunken Cities documents Goddio’s discovery story and the historical pieces the team found. On display will be three massive 16-foot-tall sculptures weighing more than 8,000 pounds each, plus more than 250 pieces of ancient Egyptian art found at the site and other pieces on loan from museums in Cairo and Alexandria.

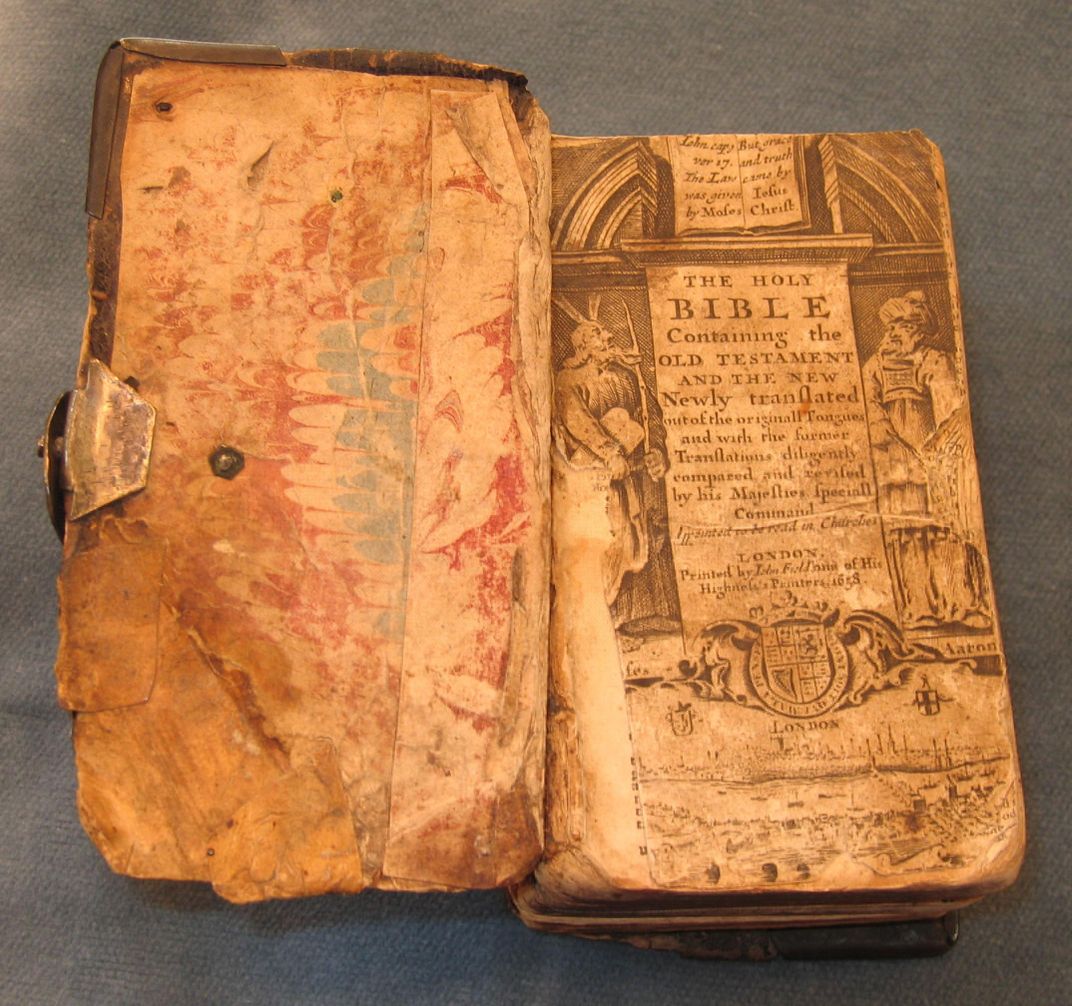

Jamestown Settlement—TENACITY: Women in Jamestown and Early Virginia

(Jamestown, Virginia; November 10, 2018 – January 5, 2020)

At the start of the New World, when settlers first arrived in Jamestown, women were considered second-class citizens. As a result, much of their history was not record, save for a few records here and there documenting marriages, deaths, or court cases. Now, those women are being brought to the forefront of history with a special yearlong exhibit at the Jamestown Settlement called Tenacity. The exhibit will have more than 60 artifacts documenting the struggles and contributions of women in the colonial days. Some of the more rare items on display include an embroidered bodice from 1610, a 17th century ducking chair and the Ferrar Papers from 1621 that documented all the original women recruited to come to Virginia.

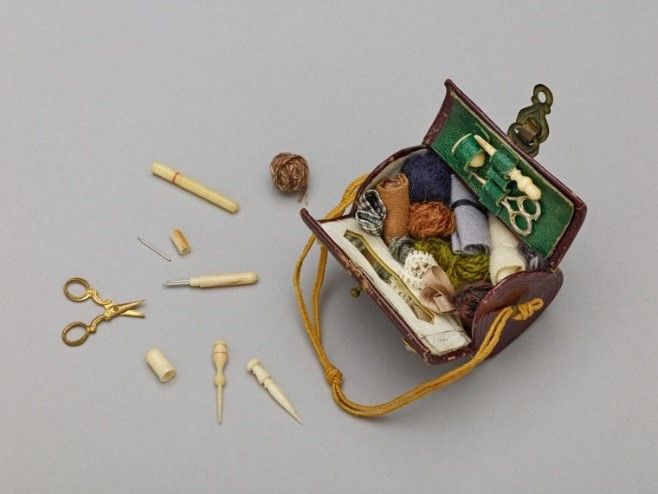

Philadelphia Museum of Art—Little Ladies: Victorian Fashion Dolls and the Feminine Ideal

(Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; November 11, 2018 – March 3, 2019)

Four dolls are at the heart of Little Ladies, an upcoming exhibit from the Philadelphia Museum of Art that explores how gender roles in Victorian times were passed on to girls through play. The dolls, named Miss Fanchon, Miss G. Townsend, Miss French Mary and Marie Antoinette, were crafted in 1860s and 1870s France and were the hot item for privileged girls during the Gilded Age. They stand about 18 inches tall and have painted heads, wigs, and leather bodies. Each doll comes with an arsenal of belongings, as well—from extensive wardrobes that include undergarments and gloves, to personal items and accessories like tiny toothbrushes and roller skates. One of the dolls’ trunks, for example, has more than 150 items. During the Gilded Age, girls were able to imagine the future life expected of them through play with the dolls, solidifying ideal social customs and cementing gender roles into the subconscious.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)