The Costumes of “Downton Abbey” Now on View at Delaware’s Winterthur Museum

Step in front of the camera and enter the Grantham household in a new exhibit in Wilmington

Last July, Winterthur Museum historian Maggie Lidz flew from Delaware to London. She was on a mission. Entering a nondescript storefront, she found herself in a sprawling, warehouse-like, mega-storage closet packed with clothing. This was Cosprop, an enormous historical-costume house, which rents to theater, film and television productions. Lidz had drawn up a list of 40 must-have costumes for an exhibition she was installing at Winterthur, and one of them was proving elusive. Digging through box after cardboard box, she finally came up, grasping the item like a diver with a pearl. Her prize was a simple apron that had been worn by Daisy, the kitchen maid, in the immensely popular British television series, "Downton Abbey."

Now, the 40 items on that list—some simple like Daisy’s dress and apron, others sumptuous like Lady Sybil’s harem pants and Lady Edith’s wedding dress—are on view at Winterthur Museum in an exhibit titled “Costumes of Downton Abbey,” and they will remain there until Jan. 4, 2015.

For four seasons, this series has followed the fortunes of the inhabitants of the fictional "Downton Abbey" in Yorkshire, England—the Earl and Countess of Grantham, along with the Earl’s formidable mother, the dowager countess, and his daughters, Mary, Edith and Sybil; and the servants of the household, supervised by Carson, the fiercely loyal butler—in a finely woven tapestry of interrelationships and intrigue. Opening in 1912, with news of the sinking of the Titanic, the show has transported viewers through the tumultuous years of World War I into the early years of the Roaring Twenties.

Although "Downton Abbey" is fiction—first and foremost, the show is about the characters and their stories—the overall backdrop of the history of this era, including the evolution of fashion and the social pecking order, is portrayed with a high degree of accuracy.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/6b/d26b75b8-8586-4c82-a04d-af3a95cc8489/da_sr3_26042012_jb__021_zps124d9a86_2.jpg)

It’s a bonus that this exhibition is at Winterthur, a palatial former estate with magnificent gardens and woods, much like Highclere Castle in Hampshire, England, which serves as the fictional Downton Abbey itself.

Located six miles northwest of Wilmington, Delaware, Winterthur, now a major decorative-arts museum, was previously the home of Henry Francis du Pont (1880-1969), and the organizers have included in the exhibit some of the du Pont family’s personal items from the same era to enrich the understanding of the way of life during that period.

“We wanted to give visitors another way to experience Downton Abbey, to see the costumes up close while being reminded of the context in which they were worn,” says Amy Delaney, an assistant curator at Winterthur. With dark walls and strategically placed spotlights, the exhibit immediately engages the visitor. Using understated diorama formats, the curators have placed mannequins in the kitchen, or in the field shooting, or in a formal room with a mantel or chandelier, and have added blown-up outtakes on the walls, relevant quotes, extended captions, and even falling snow framed by the window behind Lady Mary’s shimmering burgundy engagement dress and Matthew Crawley's tuxedo.

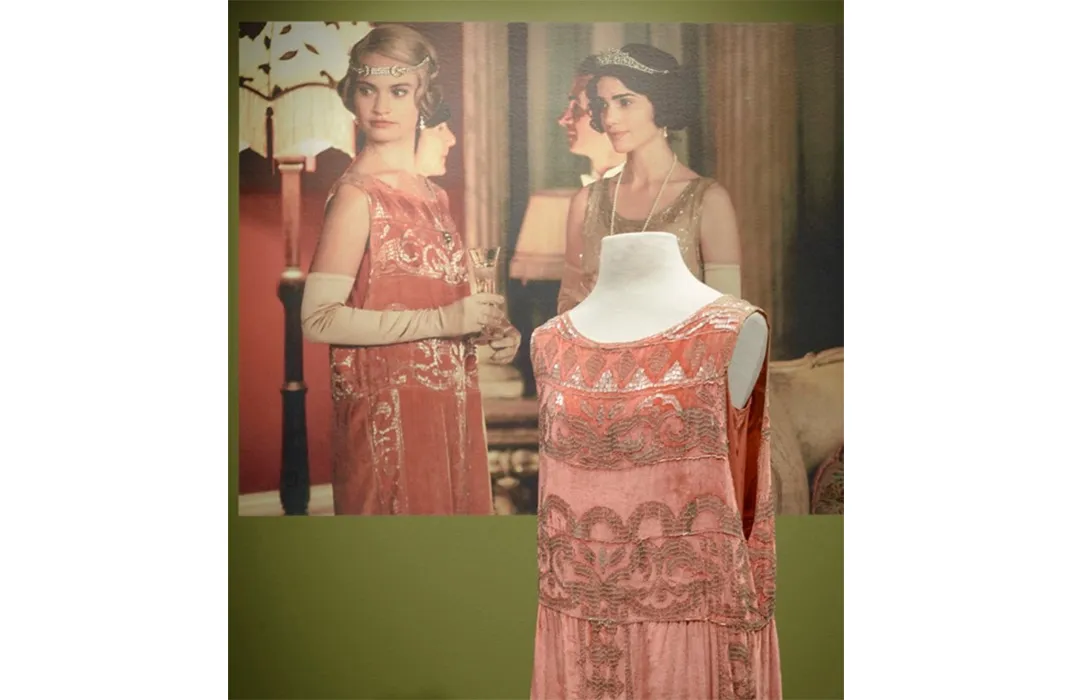

The sweep of the show's changing fashions is a visual feast. The dowager countess’s highly structured and ornamented velvet gowns in the conservative, regal style of Queen Mary provide stunning contrast to the heavily beaded early 1920s tabard-shaped dress worn by the young and adventurous Lady Rose, a Grantham cousin, in the final episode of the fourth and most recent season.

“Your niece is a flapper; accept it,” Lady Mary says wryly to Lady Grantham; Lady Rose denies it, but this stunning pink number, which the young debutante wears during her over-the-top coming-out festivities in London, does bring to mind the loosening of established conventions. While the dowager countess still frets about who will carry her bags, the budding flapper tells people, "Don't call me m'lady; call me Rose."

Lady Rose’s dress, which was rented from Cosprop, is pure vintage. In other cases, the series' designers Susannah Buxton and Carolyn McCall, started with only a fragment of beautifully embroidered or beaded vintage cloth and then built an entire costume around it. The bodice of the harem-pants costume, for example, is vintage—an embroidered fabric so fragile that it actually ripped across the back during shooting and had to be repaired between takes. Edith’s wedding dress was built around a vintage, heavily beaded train. Inspiration came from such preeminent period designers as Paul Poiret (who had introduced harem pants at a 1911 costume party in Paris), Jeanne Lanvin and Coco Chanel, with the occasional splash of detail from contemporary designers like Miu Miu or Stella McCartney.

For inquiring minds, the exhibit’s detailed captions explain which costumes or fragments are vintage and quotes from the show's designers describe in detail how they were crafted. For all the costumes, whether rented, modified, built around vintage fabric or made from scratch, the seamstresses have only seven weeks to prepare each season’s entire wardrobe.

It is surprising to learn from the exhibit the importance of the corset. Buxton has said that it’s the most important element for getting a dress "right" because the corset helps to define the line of the dress, even more than the fabric or the detailing. So the corsets for the principal women in the series are custom-made to fit them.

Of the many fashion moments in the series, the most memorable is probably when the free-spirited Lady Sybil comes downstairs for dinner wearing the harem pants (women did not wear trousers) and strikes her scene-stealing “ta-da” pose. It stuns everyone in the room that the young radical is actually having fun with clothing—a shocking departure from what was “proper” according to the strict dress codes, which defined everyone’s place in the social pecking order.

For the men—scarlet red for fox hunting, tweed for shooting, brown only for the country, never black, which was only worn in the city. And while the tuxedos worn by Lord Grantham and Matthew Crawley look similar to the one worn by Carson, the butler, in fact the tuxedos worn by the aristocrats would have been impeccably tailored to fit and made of premium vicuña, while Carson’s would have been off the rack and made of a more common wool blend. For the television production, plain wool suffices for all three, since they all look the same on camera; but in the exhibit, a swatch of the pricey vicuña is included, with that rare treat for museum-goers: “Please touch.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/75/16751467-0b29-49ab-ae5d-2e34ac89cb53/d2723_zps5f12a9b3-1.jpg)

For the servants, too, the dress code was rigid. In a scene in the first season, Daisy panics at dinnertime because she can’t carry the chicken topping into the dining room. That’s because her dress and apron are work clothes, not to be seen in the house proper.

And, of course, there are the rituals of dressing; a lady, as the series accurately portrays, couldn’t dress for dinner without the help of her maid, who laced up her corset, arranged her hair and even placed her jewelry around her neck. One of the many great one-liners delivered by Maggie Smith as the dowager countess (who, throughout the series, ruefully witnesses the crumbling of the old order) is when Lady Sybil has volunteered as a war nurse and Mrs. Hughes, the housekeeper, is helping to pack her suitcase. Her voice dripping with irony, the dowager countess says to Mrs. Hughes, “Just make sure Lady Sybil packs things she can get in and out of without a maid.”

Speaking of the crumbling of the old order, the staff at Winterthur experienced a mild dose of culture shock in dealing with the "Downton Abbey" project. As Winterthur's Amy Delaney says, “I never would have imagined the difference between working in a museum and working on a television production. Here, we treat everything so carefully. And there…you know…it’s aprons in a box. They’re props.”

But in the spirit of Lady Sybil, the curators seem to have had fun with the entire affair. Referring to H. F. du Pont’s custom-made Savile Row jacket, a caption reads: “The British liked American films, jazz and heiresses. The Americans liked British accents, gin and tailoring.”

Like so much else in this inspired exhibit, it makes you smile.

“Costumes of Downton Abbey” opened at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library on March 1 and will run through January 4, 2015. Timed tickets are required to view the exhibit.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/bond.jpg)