Darwin Would Have Loved the Cliffs of Newfoundland, Where 500-Million-Years-Old Fossils Reside

Step back in time half a billion years to a world of mysterious sea creatures that would have thrilled Darwin

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/09/c209d89e-797a-4ee9-bc8b-4e27a1e59a94/apr2017_j07_newfoundland.jpg)

Drizzling and cold, maybe 40 degrees Fahrenheit, the endless wind coming off the frigid North Atlantic, and it’s just steps to the precipice, a 30-foot drop into a foaming chaos of surf and rocks. Richard Thomas, a tall geologist in his 60s with a Prince Valiant haircut, says it’s time to take our shoes off. “I’m going to take my socks off too because they’ll just get wet in these,” he says with a chuckle, holding up one of the light blue cotton booties that you have to wear if you want to step onto this particular clifftop on the forbidding coast of southeastern Newfoundland.

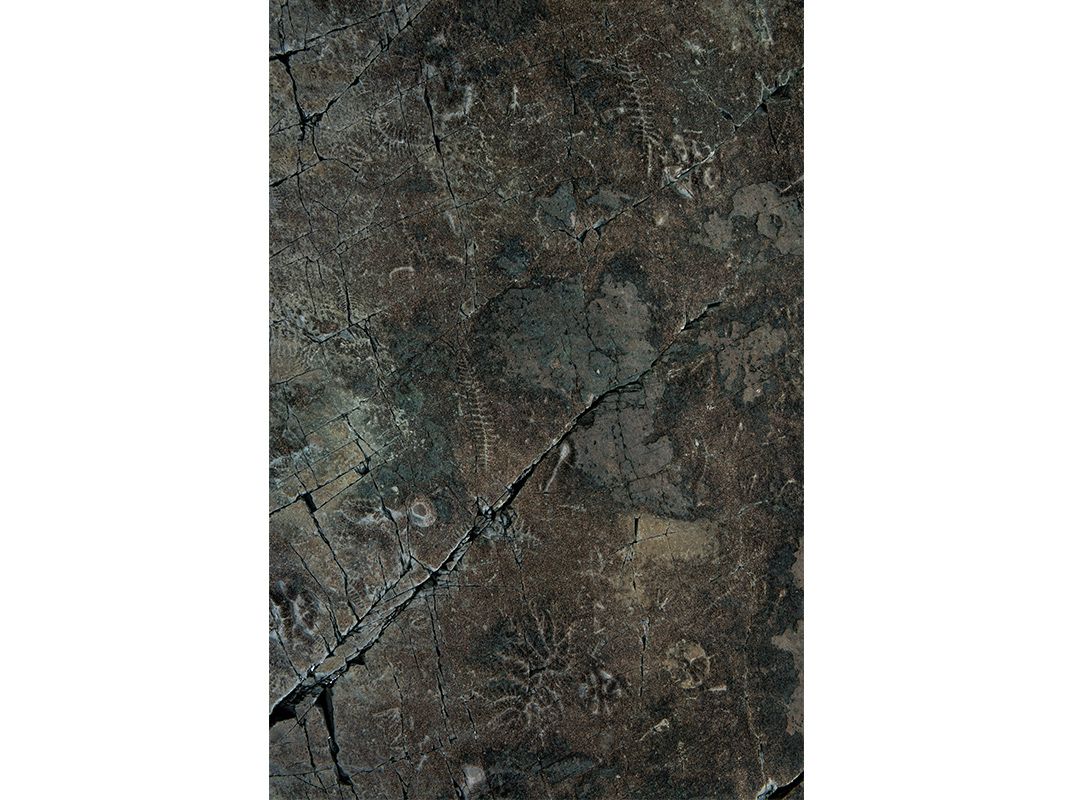

We unlace our hiking shoes, place them upside down on the ground to keep the rain out, remove our socks, pull the blue slippers onto our bare feet and tiptoe onto the bedding plane, as geologists call it. It’s about the size of a tennis court and pitched like the deck of a heeling sailboat. The surface itself is slightly rippled, and scattered all over it are what local children years ago, back when children and anyone else could romp here as they pleased, called “flowers in the rocks.” Fossils. Some look like ferns, some like cabbages, others like peace lilies. Mostly, though, they look like nothing alive today. A foot-long oval split down the middle, and each half is full of little capsules like the vesicles in an orange segment. A cone shape, about the size of a hand, like a cartoon heart.

“Thectardis,” Thomas says, pointing to the heart, and for a moment, thrown off by his British accent—he’s originally from Wales—I wondered if he said “TARDIS,” the time-traveling police box in the BBC’s mind-bending “Doctor Who.” “Thought by some to be a primitive sponge. There’s no proof, of course.” The fossils at our feet are in fact the subject of intense study and wide debate, but it’s not because of scientific controversies that the place is called Mistaken Point. The name dates to the early 18th century, and refers to the tragic tendency of ship captains to mistake this often fog-shrouded headland for Cape Race several miles up the coast, steer accordingly and run aground.

It might be nice to borrow Doctor Who’s TARDIS and return to where and when this strange heart-shaped creature lived, to answer the question of its true nature, whether animal or plant or something else entirely. Then again, that world was no place for middle-aged journalists. By nearly all accounts this clifftop originally lay on the ocean floor, as much as half a mile below the surface, in perpetual darkness, not far from where Brazil is today. And the most precise dating methods known to geochemistry show beyond a doubt that these seafloor creatures, whatever they were, lived more than 560 million years ago.

We are standing on the oldest fossils of multicellular life on the planet.

They hail from a climactic but little-understood chapter in the planet’s past called the Ediacaran Period. It began 635 million years ago, long into the great heyday of microbes and other single-celled organisms, and ended 542 million years ago, when the first groups of major animals, things that had muscles and shells and so forth, arrived in the Cambrian Period, such a wild burst of biological diversification it’s also called the Cambrian Explosion.

One of the dozens of researchers who’ve come to Mistaken Point to study these fossils is Emily Mitchell, a Cambridge University paleobiologist. She says the Ediacaran Period “is the most important transition in the history of life on earth, changing from microbial organisms only to complex large organisms and the onset of animal life.”

Another way of putting it is that these fossils represent “when life got big.” If that sounds a little like a marketing slogan, it is: Experts seized on the phrase when they petitioned Unesco in 2014 to recognize Mistaken Point as a World Heritage site. The agency agreed to do so just last year, calling the fossils “a watershed in the history of life on earth.”

Thomas, who is the jolliest pessimist I’ve ever met, tends to think life on earth is at another watershed, though this one is self-inflicted. “For me, it puts everything into perspective, how arrogant we are,” he says, reflecting on these vanished life-forms. “We’ve been around for a blink of an eye. People say, Save the planet! Well, the planet will survive us. Earth will endure. Something will replace us. Some days I think, the sooner, the better!” He laughs.

Standing on the bedding plane, I feel the cold November damp seeping through the blue slippers, which Thomas later explains are called Bamas, a brand of insulating “boot socks” worn inside Wellingtons and beloved by sheep farmers everywhere. Scientists as well as tourists are required to wear them to minimize wear and tear on the fossils.

“Charniodiscus,” Thomas says, crouching by a fossil about a foot long. It looks like a giant feather with a bulb at the tip of the quill. “That’s the holdfast, attached to the seabed,” he says of the disk. “This is the stem. And there’s the frond.” This signature Ediacaran creature would have swayed in the ocean currents like kelp. Its shape is so distinct, so well defined, that it clearly didn’t die slowly and decompose. “It appears that something came and knocked it down,” Thomas says.

The same goes for all the creatures here, victims of catastrophe half a billion years ago.

**********

Charles Darwin, refining his theory of evolution in the 1860s, famously lamented the total lack of fossils older than those from the Cambrian Period. The “difficulty of assigning any good reason for the absence of vast piles of strata rich in fossils beneath the Cambrian system is very great,” Darwin wrote with a sigh. To his critics, that absence was a fatal flaw in his theory: If evolution was gradual, where’s the evidence of complex creatures that lived before the Cambrian? Answer: Mistaken Point.

It’s not the only site of its kind; a cluster of pre-Cambrian fossils found in 1946 in the Ediacara Hills of southern Australia would give this newly recognized geological period its name. But no Ediacaran Period fossils are more numerous, better preserved, bigger, more accessible or older than those at Mistaken Point, which were discovered 50 years ago this summer by a geology graduate student and his undergrad assistant, both at Memorial University in St. John’s, Newfoundland. The surprise find was announced in the journal Nature, and scientists have been traipsing over the misty coastal barrens to these cliffs and ledges ever since.

In part to safeguard the area from fossil thieves, the provincial government in 1987 designated a sliver of coast as the Mistaken Point Ecological Reserve, now 11 miles long. The fossils themselves are off-limits to the public except in two particular spots, called the D and E beds, and to visit you must be on a tour led by an official guide. Tours run from May to mid-October and depart from the Edge of Avalon Interpretive Centre in the tiny town of Portugal Cove South. Tourists drive down a gravel road several miles to a trailhead, then hike through wild heaths and over streams to the fossil beds.

Just as English literature has Beowulf, an important text that causes stupefying boredom in all but a few, geology has Pangea, the tedious theory of how all the continents once were joined together hundreds of millions of years ago in a great mass, and eventually drifted apart into the different puzzle pieces we know today. Maybe Pangea seems boring because of the way we first learn about it in junior-high science class, or maybe it’s simply impossible to comprehend unless you’re a geologist. But Pangea and the related concepts of plate tectonics explain how a seafloor near Brazil ended up as a clifftop in Newfoundland.

What’s so amazing about Mistaken Point is that the ancient imponderable drama is still unfolding right on the bedding plane, and you can touch it. There are patches of charcoal- and rust-colored material, shaped like puddles but gritty and solid like mortar, that are about an eighth of an inch deep. This material once blanketed this clifftop, but as the stuff has worn away in places, the fossils have emerged—thousands so far. Geologists have identified this mortar-like layer as ash, and therein lies the clue.

These bottom dwellers, mostly sedentary and soft-bodied but in a wonderful profusion of primitive shapes, were suddenly buried in a deadly flood of debris spewing from nearby volcanoes—an “Ediacaran Pompeii,” one paleontologist called it. Guy Narbonne, a paleontologist at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, and a leading authority on the Ediacaran Period, began studying the Mistaken Point fossils in 1998. “The first time I saw it I was simply astonished,” he says. “The organisms were all killed catastrophically where they lived, preserving entire community surfaces. Looking at it now is like snorkeling over a 560 million-year sea bottom. Everything is exactly as it was. It’s the one place in the world where you can actually see an Ediacaran sea bottom, and that’s because of the ash.”

After Thomas and I doff our Bamas and don our boots, we hike back to the trailhead, then ride in the truck about a mile down the coast. He wants to point out an oddity that verges on the revolutionary. Outside the public viewing space, it was first documented by the Cambridge University paleobiologist Alexander Liu on one of his research trips here. The marking on the rock looks rather like a fat pencil, the fossil remains not of a creature but of its travels—what experts call a trace. The minute waves and ridges most closely resemble those created by a sea anemone moving across a soft surface, as Liu and co-workers found when they brought sea anemones into their lab and analyzed the trails they leave in a sandy surface as they move across it at about one inch every few minutes. “This is the oldest, (fairly well-) accepted evidence of animal locomotion in the fossil record,” Liu says in an email, “the first evidence for movement by an organism with muscular tissue.” To nail down proof that animals were already at large in the Ediacaran is no small thing. “If they turn out to be animals,” Liu says, “they effectively demonstrate that the Cambrian Explosion was a much more drawn-out, transitional event than has been considered.”

Rumbling in the truck back to Thomas’ office in the interpretive center—he’s employed by the provincial government to monitor and protect the fossil sites—we see several small white birds in the dirt road up ahead. An avid birder, he stops the truck and grabs binoculars off the dashboard. “Snow buntings!” he says, and flashes a big, almost optimistic smile.

**********

We live nowadays, of course, in a degraded world, not just environmentally but numerically. Billionaires are a dime a dozen. We’re such data gluttons that the once stupendous gigabyte—a billion bytes!—is next to nothing. So how do you even begin to sense the immensity of life making its way half a billion years ago?

Fortunately there is the white-capped Atlantic in its primordial glory, the fog clinging to the vast, unpeopled rolling heath, the jagged rocks glazed with drizzle, the roaring wind and the crash of the churning green waves. Even the necessity to take off your shoes is a grateful act, reminiscent of sacred ritual. “Underfoot, petrified deep time rises in welts / to prod our soles, here and there / breaking into sudden bas-relief,” the Canadian poet Don McKay writes in his stirring ode “Mistaken Point.” If you listen to it you might get the other meaning of “soles.”

Related Reads

A New History of Life: The Radical New Discoveries about the Origins and Evolution of Life on Earth

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.