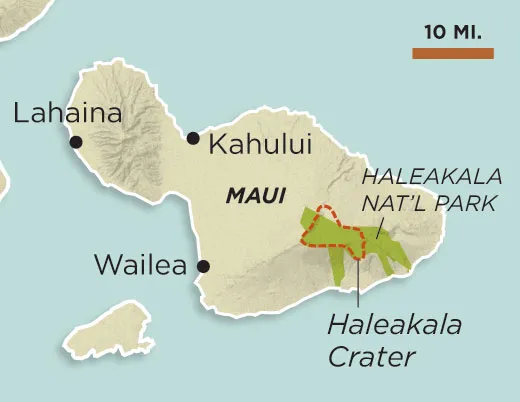

Descending Into Hawaii’s Haleakala Crater

A trip to the floor of the Maui volcano still promises an encounter with the “raw beginnings of world-making”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Haleakala-Crater-Peles-Paint-Pot-631.jpg)

Entering Haleakala Crater, the enormous mouth of Maui’s largest volcano, in the Hawaiian Islands, feels like an exercise in sensory deprivation. At the crater floor, a desolate expanse of twisted, dried lava reached after a two-hour hike down a trail carved into its wall, the silence is absolute. Not a breath of wind. No passing insects. No bird songs. Then I thought I detected drumming. Was it the ghostly echo of some ancient ritual? No, I finally realized, it was my own heartbeat, thundering in my ears.

In 2008, National Park Service acoustic experts found that the ambient sound levels within Haleakala crater were near the very threshold of human hearing—despite the popularity of the park. Around one million people a year visit the park, many of whom also ascend to its highest point—Haleakala’s 10,023-foot summit—and peer down at the vast field of dried lava below, which, in 1907, the writer and adventurer Jack London called “a workshop of nature still cluttered with the raw beginnings of world-making.”

The now-dormant volcano, which emerged from the Pacific Ocean more than a million years ago, takes up fully three-quarters of Maui’s landmass. Although its interior, whose rim is 7 1/2 miles long and 2 1/2 miles wide, is commonly called a crater, geologists refer to it as an “erosional depression” because it was created not by an eruption but by two valleys merging. Still, there has been frequent volcanic activity on its floor. Carbon dating and Hawaiian oral history suggest that the last eruption occurred between 1480 and 1780, when a cone on the mountain’s southern flank sent lava surging down to La Pérouse Bay, about two miles from Maui’s southernmost tip, near the modern resort town of Wailea.

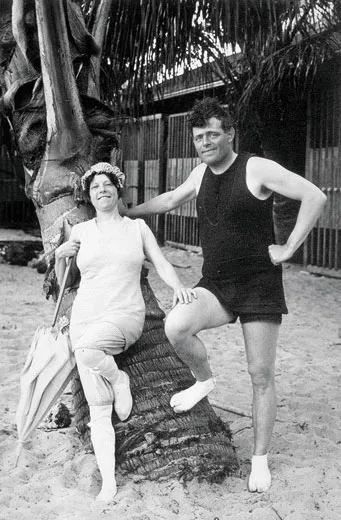

Only a small number of visitors to Haleakala descend to the crater floor. Those who make the effort, as London did on horseback with his wife, friends and a band of Hawaiian cowboys, find themselves in a strangely beautiful world of brittle, contorted lava. “Saw-toothed waves of lava vexed the surface of this weird ocean,” wrote the author of The Call of the Wild, “while on either hand arose jagged crests and spiracles of fantastic shape.” Initial impressions of the crater as a lifeless wasteland are quickly dispelled. Delicate lichens and wildflowers dot the landscape, along with a bizarre plant found nowhere else on earth called the ahinahina, or Haleakala silversword. The plant grows for up to half a century as a dense ball of metallic-looking leaves, produces a single tall spire that flowers only once, with a brilliant, blood-red blossom, then dies. Endangered Hawaiian birds thrive here, including the largest nesting colony of Hawaiian petrels, or uau, which let out a peculiar barking cry, and Hawaiian geese, called nene.

While much of the crater is the ocher and ashen color of alpine cinder desert, the eastern reaches are a lush green, with swaths of virgin fern forest. London’s group camped here, surrounded by ancient ferns and waterfalls. They ate beef jerky, poi and wild goat, and listened to the cowboys sing by the campfire, before descending to the Pacific Ocean via a break in the crater called the Kaupo Gap. “And why...are we the only ones enjoying this incomparable grandeur?” he wondered aloud, according to his wife, Charmian, in her 1917 memoir, Our Hawaii.

On my solitary expedition, the silence of Haleakala did not last long. As I picked my way across the lava fields, the first gusts of wind arrived, then dense clouds that were filled with icy drizzle. Soon the temperature was plummeting and I could barely see my feet for the fog. Thunder was booming by the time I reached Holua cabin, one of three public refuges crafted in 1937 from redwood with help from the Civilian Conservation Corps. They’re the only man-made shelters in the crater other than park ranger cabins. I lit a wood-burning stove as the sky erupted in lightning. For the rest of the night, tongues of crackling light illuminated the ghostly, contorted lava fields. Pele, the volatile ancient Hawaiian goddess of fire and volcanoes, must have been displeased.

The story of Haleakala National Park is inseparable from that of Hawaii itself, whose transformation from independent Pacific kingdom to 50th U.S. state has largely been forgotten on the mainland. When the federal government created the park in 1916, less than two decades after it seized the archipelago, it ignored the crater’s cultural importance for native Hawaiians. But in recent years, Haleakala’s ancient status has gained new attention.

Part of the world’s remotest island group, Maui was first settled by humans around A.D. 400-800, possibly by Polynesians,who arrived in outrigger canoes after navigating 2,000 miles of open sea. Called Alehe-la by the ancient Hawaiians, the island’s imposing peak eventually became known as Haleakala, or “House of the Sun.” It was from its sacred heights, legend holds, that the demigod Maui lassoed the sun as it passed overhead, slowing its passage across the sky to prolong its life-giving warmth.

Though ancient Hawaiians built their villages along Maui’s lush coast and the slopes of Haleakala, many made visits to the crater, although how many are not known. “There was no permanent habitation,” says Elizabeth Gordon, the park’s cultural resources program manager. “Just temporary campsites, sometimes in caves and lava tunnels. But it was a very special place.”

The summit was the site of religious ceremonies, says Melanie Mintmier, an archaeologist working with park service staff in Haleakala. “There are ancient ritual sites along the rim, and sacred places within the crater that we know about from legends and oral traditions.” The ancient Hawaiians came also to hunt birds, which provided feathers for ceremonial cloaks as well as food, and to carve adzes out of basalt from a quarry on the western side of the rim. Many foot trails wound through the crater, and a path was also paved. Parts of it survive, as well as the remains of temple platforms, stone shelters and cairns. But park authorities won’t disclose the locations because many of the places remain sacred. “Hawaiians today use some of the same sites in Haleakala as their ancestors used for ceremonial purpose,” says Gordon. “It’s a vibrant, living culture.”

“An array of rituals still occur on Haleakala,” says Kiope Raymond, associate professor of Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawaii Maui College (and a native Hawaiian). “Celebrations of the season, the solstice, commemorations, or worship of different deities.” Visitors are unlikely to notice the goings-on, he says, because practitioners often visit sacred places alone or in small groups. One rite that Raymond says is still practiced on Haleakala is the burial of the umbilical cords of newborn children alongside the bones of family ancestors. “As with many Native American people, the bones of the dead are [considered] repositories of spiritual energy, or mana, and are revered by native Hawaiians.”

The cultural isolation from Europe of the Hawaiian Islands ended in 1778, when the British explorer Capt. James Cook weighed anchor on the Big Island. Eight years later, a French explorer, the Comte de La Pérouse, landed on Maui. European and American traders, missionaries and whalers followed, bringing Christianity and devastating diseases. The first known newcomers to ascend Haleakala were a trio of Puritan preachers from New England working at a mission in the Maui port of Lahaina. Led by native Hawaiians on August 21, 1828, William Richards, Lorrin Andrews and Jonathan F. Green journeyed from a camp at the mountain’s base to the summit. Near dusk, they gazed down at the crater floor. In the Missionary Herald the following year, they reported that the beauty of the sunset there could be reproduced only by “the pencil of Raphael.”

Another intrepid tourist eager to see the crater was a little-known reporter who called himself Mark Twain. At age 31, in 1866, Twain had tried surfing in Oahu for the Sacramento Union (“None but natives ever master the art of surf-bathing thoroughly,” he reported) and marveled at the active volcanoes on the Big Island. Intending to stay but a week in Maui, he ended up staying five, missing his deadlines entirely. “I had a jolly time,” he wrote. “I would not have fooled away any of it in writing...under any consideration whatever.” One dawn, Twain joined a group of tourists at Haleakala’s summit and was awe-struck; he called the sunrise “the sublimest spectacle I ever witnessed.” He also reported rolling giant rocks into the crater to watch them “go careening down the almost perpendicular sides, bounding three hundred feet at a jump.”

In his 1911 travel book about the Pacific, The Cruise of the Snark, Jack London urged Americans to take the six-day steamer from San Francisco to Honolulu and the overnight boat to Maui to see the crater for themselves. “Haleakala has a message of beauty and wonder for the soul that cannot be delivered by proxy,” he wrote. The naturalist John Burroughs concurred, praising it in his 1912 essay “Holidays in Hawaii.” Worth Aiken, the local guide who took him to the summit, would recall that Burroughs stood spellbound for about ten minutes at the rim, then declared it “the grandest sight of my life.” In a later letter to Aiken, Burroughs compared the crater with the active volcanoes of Hawaii’s Big Island. “Kilauea is a glimpse into the depths of Hell, but Haleakala is a view of the glories of Heaven: and were the privilege ever given to me to see again one of the two, I would without hesitation return to Haleakala.”

In 1916, Congress created the Hawaii National Park, which included Haleakala, as well as Kilauea and Mauna Loa on the Big Island, then failed to provide any funding. As one congressman noted, “It should not cost anything to run a volcano.” Few policymakers seemed to care what native Hawaiians thought about turning their sacred summit into a tourist attraction.

Hawaii’s Queen Liliuokalani had been deposed in a coup only a few years earlier, in 1893, by a coalition of American and European businessmen, backed by U.S. sailors and Marines. Despite a subsequent rebellion by native Hawaiians and a massive petition for a return to independence, immigrant settlers continued to pressure the United States to annex the islands.The nation did so in 1898, after the Spanish-American War convinced Congress that the archipelago was an essential springboard for Pacific influence. After annexation, the Hawaiian language was no longer taught in schools, and the native culture withered.

Initially, there was little increase in the number of haole (whites) and other non-Hawaiians who made the time-consuming journey to Maui’s new park. The first full-time ranger was not appointed until 1935, when completion of a road to the summit began to bring more visitors. In 1961, the National Park Service declared Haleakala a separate park, while maintaining strict environmental protections.

But protection of the crater’s cultural heritage lagged until the so-called Hawaiian Renaissance of the 1970s, a resurgence of Hawaiian culture partly inspired by Native American movements. At the same time, a new generation of Hawaiians began to express frustration that their ancestral relationship to the land had been severed.

“The resentment does exist and it’s an uncomfortable thing,” says Sarah Creachbaum, the park’s current superintendent. “But the staff is working very hard to break down barriers. We’re trying to incorporate traditional knowledge into management practices.” The park now employs native Hawaiian rangers, she says, and seeks to use native oral history and environmental knowledge in its programs. New projects proceed under consultation with kapuna (family elders) and community figures, although the process is complicated by the sheer number of native Hawaiian groups and organizations. (Unlike many Native American tribes, native Hawaiians are not recognized as a distinct group by the federal government and have no single negotiating body or voice.)

“For the time being, many Hawaiians are grateful that the National Park Service is playing a protective role for the land that their ancestors once stewarded,” says Kiope Raymond. “But we also see the need for Hawaiians to get back a kind of sovereignty over their land, which was taken from them without their assent.” He points to arrangements on the mainland, where Native Americans are given a degree of sovereignty over their own land, as models for what might be done on Maui. (An example is the Monument Valley Navajo Tribal Park in Arizona and Utah, where the Navajo are successfully managing an iconic American landscape.) “The stewardship of Haleakala should be returned to Hawaiians,” Raymond says.

“Haleakala holds a high number of endangered species,” says Matt Wordeman, president of Friends of Haleakala National Park, a volunteer group that helps repair cabins, remove invasive plants and support the breeding of Hawaiian geese. He says every national park has to balance everyday needs with preservation, “and Haleakala comes down heavily on the side of preservation.” No walking off-trails, no fires and no camping in undesignated areas.

Park superintendent Creachbaum says invasive species are the biggest challenge. In Hawaii, where outside plants and animals arrive daily, controlling them is almost a Sisyphean task. In the past ten years, axis deer, native to India, have been introduced to Maui—most likely by hunters—and have started to jump fences erected around the park in the 1970s. “Just like humans, other species discover that Hawaii is a great place to live,” says Creachbaum.

And the crater is a great place to visit. On my last morning, I awoke just as golden shafts of sunlight began creeping across the lava fields, illuminating the cliffs behind me. I scrambled up the rocks behind my cabin, entered a cave, whose use as a campsite may go back a thousand years, to be enveloped once again in silence. “If you spend any time at all inside Haleakala,” Raymond had told me, “you will be overcome by what Mark Twain called its ‘healing solitudes.’ It induces tranquillity and encourages reflection. Peoples close to the earth all find summits sacred. It’s as close as one can get to the heavens.”

Frequent contributor Tony Perrottet is the author of The Sinner’s Grand Tour. Photographer Susan Seubert is based in Portland, Oregon, and Maui.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)