How Do You Copyright a Clown Face? Paint It On an Egg

Since the 1940s, eggs have been the canvas of choice for registering performers’ unique makeup designs

:focal(523x309:524x310)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/ce/63ce643e-9c2a-4339-9f18-307b8136f9c5/dsc_0058_2.jpg)

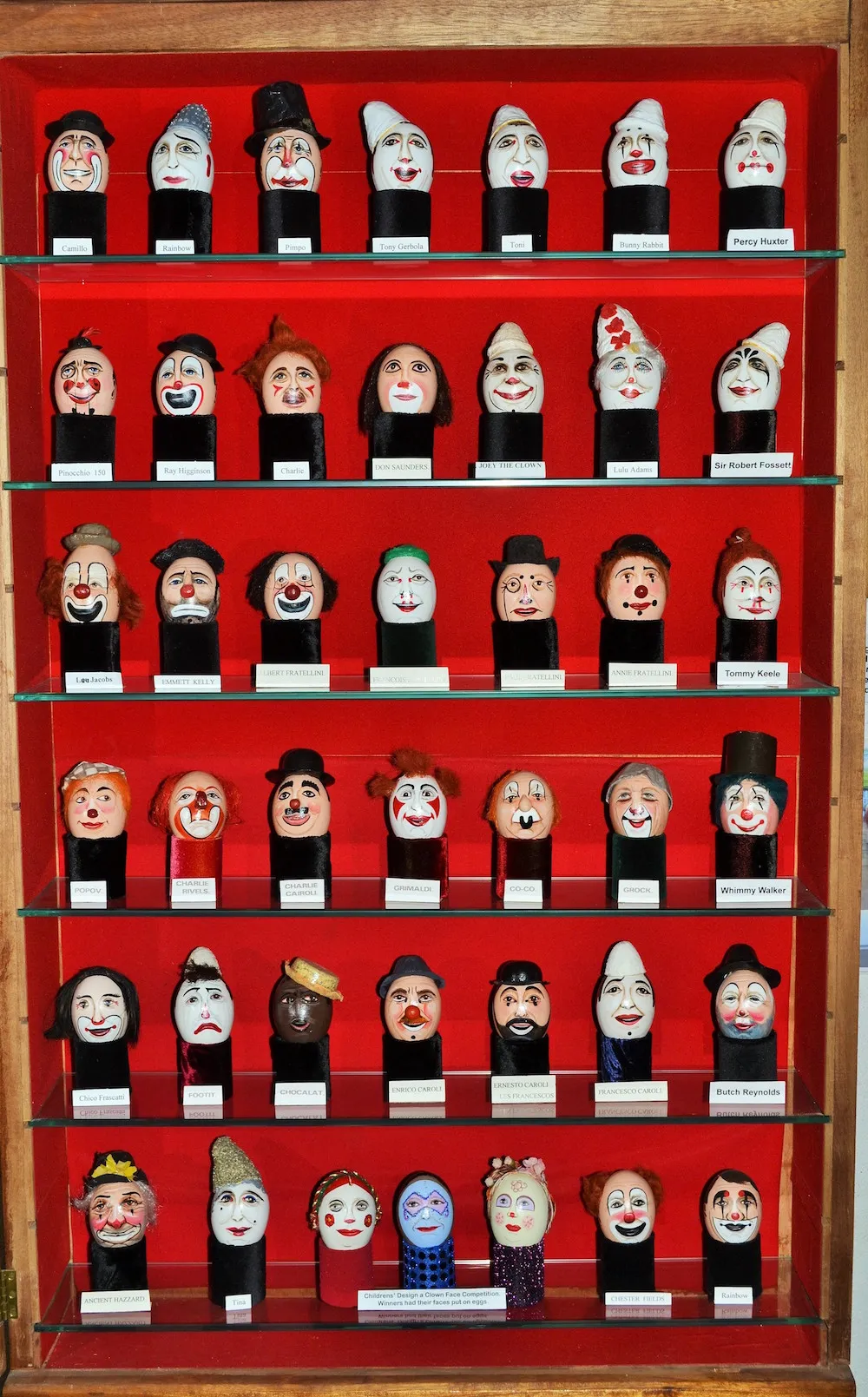

Debbie Smith has her work cut out for her. Since 2010 she has been the artist responsible for recording the likeness of every clown registered with Clowns International, the oldest established organization for clowns in the United Kingdom. It's a seemingly straight-forward task—that is, until you discover what she uses as a canvas: eggs.

She has tradition to thank for using such a tiny—and fragile—canvas. The late Stan Bult, founder of the International Circus Clowns Club (now Clowns International), began the practice in the 1940s. Though not a clown himself, Bult was a clown enthusiast, and would capture the appearances of various clowns by painting them onto hollowed-out eggs as a way to copyright their facial features, ensuring that no two clowns looked the same. Eventually the collection grew into what is now the Clown Egg Registry, a compendium of hundreds of eggs housed inside the London Clowns’ Gallery-Museum in the UK.

Over time, future egg artists transitioned to using ceramic eggs rather than real ones, since they’re less prone to breakage, but beyond that the technique remains largely the same, with artists recreating everything from a clown’s bulbous red nose to his or her polka-dot tie to the most minute details that set one clown apart from the rest.

“If they have a red nose, I’ll use clay to give a 3D effect to it, which helps distinguish that character,” Smith tells Smithsonian.com. “It’s more challenging if I’ve never met the clown, or if their character doesn’t use a lot of makeup. Then you’re basically doing a portrait of their face. If I’ve seen them perform or have some sort of history with them, then it becomes more real. For instance, when I created my husband’s egg portrait [his stage name is Miki the Clown], and he sat for me, I was thinking that it didn’t actually look like him as a clown. And then I finally realized it was because he didn’t do the pose he would normally do as a clown, where he opens his eyes wide and his mouth a little bit.”

It’s not uncommon for Smith, a clown herself (aka Jolly Dizzy the Clown) to spend up to three days painting a portrait, often working on several in tandem, painting the clowns either in person or from a photograph. She’ll also create duplicates of eggs, one for the clown to keep as a memento and one for the museum, which is housed inside the organ room of the Holy Trinity Church, the final resting place of the beloved Grimaldi the Clown, who passed away in 1837 and is noted for boosting the popularity of clowning to a worldwide audience.

Currently the gallery houses 240 eggs. Of that collection, 24 are Stan Bult originals and 43 are replicas of eggs that either broke or were lost over the years.

“When I first came to London in 1970, there was a restaurant in the West End called Clowns,” Faint tells Smithsonian.com. “At that point I wasn’t a clown. I went there for dinner and I remember seeing the eggs in a case. When the restaurant closed the eggs disappeared, and [Clowns International] had no knowledge of what happened to them. In 1988, it was decided to restart the clown register of faces. I started working at the museum the year before, and we began replicating the original clown faces, using photos and magazine article clippings from [Bult’s] time, while also recording the faces of living clowns. A few years ago I got a phone call from the family of a woman who had died. They found the original 24 eggs in her spare bedroom, and asked us if we wanted them for the gallery.”

Today new eggs are being added to the gallery whenever a new clown registers with Clowns International, and the collection received a recent boost of interest with the release of “The Clown Egg Registry,” a book of photographs of the eggs by Luke Stephenson that reached U.S. bookstores earlier this year. Although Faint admits that the clown industry as a whole is changing with the times, he doesn’t foresee it ever disappearing entirely. His reasoning: Who doesn’t like to laugh?

“[Clowning] will continue forever,” he says. “It's great making people laugh. Like Mel Brooks once said, laughter blows the dust off your soul.”

The London Clown’s Gallery-Museum is open on the first Friday of the month from noon to 5 p.m.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/ce/63ce643e-9c2a-4339-9f18-307b8136f9c5/dsc_0058_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/76/6976b340-994d-4e51-89d6-21671841d056/stan_bult.jpg)