How to Tour the World’s Greatest Science Labs

Around the globe, physics and astronomy labs—some on mountaintops, others underground—welcome visitors to tour the premises

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130403012123CERN-Tour2.jpg)

They may be at work pursuing the greatest mysteries of the physical world—yet the men and women who operate the world’s most prestigious physics and astronomy laboratories aren’t necessarily too busy to host guests. Throughout the world, physics and astronomy labs—many of them shimmering like stars in the wake of tremendous discoveries and achievements, some on mountaintops, others underground—welcome visitors to tour the premises, see the equipment, look through the telescopes and ponder just why they almost always make you wear a hardhat.

CERN. It’s the little things in life that really matter to the researchers at CERN, or the European Organization for Nuclear Research. This facility—located near Geneva, Switzerland—has gained superstardom over the last year, after announcing the discovery of what had been a holy grail of physics for decades—sometimes called the “God particle.” First predicted by physicist Peter Higgs in 1964, the then-theoretical particle, which pops from a field that is believed to give other particles their mass—became known as the Higgs boson before more recently assuming its grandiose nickname. CERN’s $10 billion atom smasher, called the Large Hadron Collider, had been at work for several years in its subterranean home in the Alps, beneath the French-Swiss border, colliding protons at high speeds before rendering what seemed to be evidence for the God particle in 2012. After a year of analyzing data, CERN researchers officially announced in March that it was all but certain: They’d captured a handful of real, honest-to-God Higgs bosons (visible only via a peak on a graph of data). Should you be in the charming Swiss countryside this summer, consider taking a guided tour of this most distinguished of the world’s great physics laboratories.

Did you know? CERN’s researchers helped develop the World Wide Web as a way to share data among scientists.

Gran Sasso National Laboratory. Bundle up, say goodbye to the Italian sun and take a tour of the austere bowels of one of the largest underground laboratories in the world. The Gran Sasso National Laboratory welcomes visitors, who get to see some of the world’s finest physicists in action as they work on a variety of experiments. The laboratory is located thousands of feet below ground, beside a freeway tunnel within Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga National Park, and as wolves, deer and foxes in the wild country above chase and gobble each other up in their timeless ways, scientists in the Gran Sasso lab are busy pursuing the puzzles of neutrino physics, supernovas and dark matter. As part of an ongoing joint project, the Gran Sasso lab receives neutrino beams fired from the CERN lab, some 500 miles away. By observing a pattern of oscillations in such beams, protected from interfering particles by rock and water, scientists have been able to prove that neutrinos do have mass. (Still wearing that hardhat, I hope?)

W. M. Keck Observatory. Some of the largest telescopes on Earth stand on the summit of Mauna Kea, the 13,800-foot volcano on the Big Island of Hawaii. These instruments—about eight stories tall and weighing 300 tons each—have allowed researchers to pursue the most vexing of the universe’s questions: How do solar systems form? How fast is the universe expanding? What is its fate? Visitors age 16 and older can tour the site at a fee of $192. The tours last a marathon eight hours and include transportation, dinner, hot drinks and hooded parkas—which few tourists ever even think of packing along to Hawaii. WARNING: The high altitude of the site can pose pressure-related health hazards, and SCUBA divers should not visit the Keck Observatory shortly after any significant time spent underwater.

Sanford Underground Research Facility. A century and a half ago, who could have known that beneath the lawless land of the Black Hills would one day be one of the world’s most sophisticated physics labs? The Sanford Underground Research Facility is located in the old Homestake Gold Mine in South Dakota, reaching 4,850 feet below ground. Like other subterranean particle observation labs, Sanford’s Homestake facility relies on the Earth itself to eliminate radiation and associated nuisances from the environment and allow scientists to conduct their experiments free of cosmic noise and interference. The Sanford laboratory’s focal points include the origin of matter, the properties of neutrinos and the ubiquitous pursuit of dark matter, which makes up a majority of the mass in the universe but which physicists have yet to positively identify. Tours of the Homestake site are available. Visitors must first stop at the reception center on Summit Street in the adjacent town of Lead, open weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. Once on the Sanford premises, they can neither smoke nor drive more than 10 miles per hour.

Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. Even the world’s brainiest thinkers won’t think you’re lazy if you call it “LIGO.” This project consists of two sites roughly 2,000 miles apart—the distance being an essential component of LIGO’s research. The facilities are designed to detect gravitational waves, ripples in the very fabric of spacetime that are generated by cataclysmic events. Albert Einstein predicted their existence as part of his theory of general relativity in 1916. LIGO’s technology could detect these vibrations. To be certain that the sensors—contained in 2.5-mile-long vacuum tunnels—aren’t simply picking up the tremblings of local earthquakes, LIGO uses two locations distant from each other. One is in Hanford, Washington, the other in Livingston, Louisiana. Public tours of the Livingston LIGO site are scheduled about once per month and custom tours can be requested. To visit the Hanford site, call ahead.

SETI Institute. It was founded in Mountain View, California, in 1984, and since then, well, this alien-hunting institute hasn’t really discovered what it has been looking for. Not that scientists with the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute aren’t trying. The SETI Institute uses the Allen Telescope Array, near Mount Lassen, to listen closely to the sounds of the stars, hoping to receive signals that might indicate the presence of other intelligent beings in the universe. Let’s just hope they’re a little less intelligent than we are. After all, some scientists have voiced concerns about what will happen if humans actually succeed in making contact with an alien species. In 2011, researchers at Penn State and NASA jointly released a report in which scientists warned that aliens might enslave, kill or eat us. Undaunted by what fate may befall us—and in spite of recent budget constraints—the SETI Institute continues its search for extraterrestrial intelligence. The Allen Telescope Array is located at the Hat Creek Radio Observatory. Here, the heavily forested location makes for a quiet and scenic getaway. The riffles of Hat Creek are famed for their wild trout, while frequently clear night skies make for fine tent-free summertime camping in the nearby Lassen Volcanic National Park. Visitors to the Hat Creek Observatory can take self-guided tours.

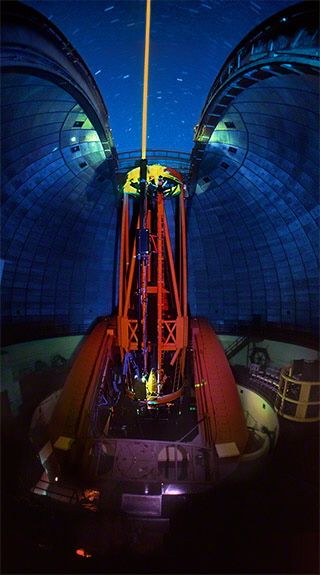

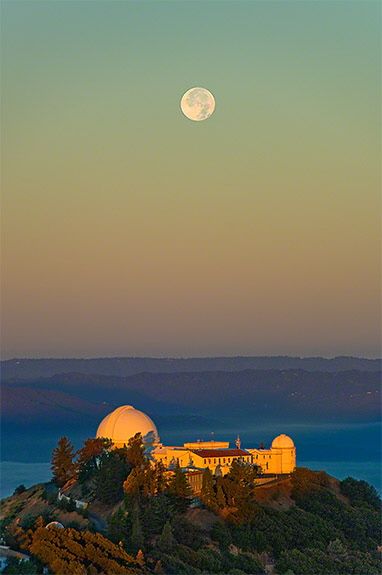

Lick Observatory. Perched upon the 4,200-foot Mount Hamilton, near San Jose, California, the Lick Observatory is where astronomer Geoff Marcy of UC Berkeley, along with several colleagues, has helped identify hundreds of planets outside our own solar system since 1995, when scientists discovered the first such planet orbiting a sun-like star.* It was a pair of Europeans—Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, using the Haute-Provence Observatory—who first looked closely at the sun-like 51 Pegasi, located about 50 light-years away in the Pegasus constellation. In this star they observed an oscillating wobble—a telltale sign of an orbiting planet. They published their discovery in October 1995. A week later, Marcy took a second look at 51 Pegasi and confirmed the planet’s discovery. The planet became known as 51 Pegasi b. Marcy and his colleagues went on to discover hundreds more planets. For visitors, Lick Observatory is almost as friendly as a public museum. The site—at which James Lick lies buried beneath one of the telescopes—is open most days of the year and includes a bed and breakfast. Musical performances, weddings and other events are held on the summit. Check out Lick Observatory’s website for more information about visits.

* In 1992, astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail discovered the very first extrasolar planets—though these were orbiting PSR B1257+12, believed to be the stellar corpse of a supernova. Thus, the planets are considered extremely unlikely to bear evidence of alien life.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Off-Road-alastair-bland-240.jpg)