The Making and Remaking of the Original Ice Hotel

Often imitated but never duplicated, the world’s original ice hotel turns 25 this year

The remote Swedish town of Jukkasjärvi—located 120 miles above the Arctic Circle—was never the natural choice for a winter tourist destination. Known more for its plentiful summer offerings, like rafting trips and fishing expeditions, the small village off the Torne River turned into an icy ghost town in wintertime. Then, in the late 1980s, a local Swedish entrepreneur had a whimsical idea that changed everything: combine ice with art to attract visitors during the cold winter months. Twenty-five years later, Jukkasjärvi is the epicenter of the winter tourism phenomenon known as the ice hotel, where adventurous guests pay to spend the night in a room crafted entirely from ice. Over the years, imitators have sprung up from Canada to Japan, but Jukkasjärvi's Icehotel remains the first and the biggest.

"More or less, it was a coincidence," says Icehotel's creative director Arne Bergh of the hotel's creation. For years, local businessman Yngve Bergqvist had watched as Jukkasjärvi filled with tourists attending conferences or looking for adventure on the Torne, one of Europe's cleanest rivers, during the summer, while the town emptied in the winter. Hatching a plan to keep the place in business during its coldest months, Berqvist traveled to some of the world's coldest places, including Sapporo, Japan, during its annual winter ice festival. Surrounded by the tradition of ice sculpting, Bergqvist had an idea—bring icy art to Jukkasjärvi. In 1989, the town hosted its first ice sculpting seminar, inviting artists from Japan to come and work with ice pulled from the Thorne. In 1990, the art moved inside a 645-square-foot igloo on the banks of the Torne.

The next year, by chance, Bergqvist's igloo exhibition space hosted its first overnight occupants when a group of tourists who had come to Jukkasjärvi for a winter business retreat found themselves without a place to stay. Someone suggested the igloo and, armed with reindeer pelts and sleeping bags, 15 visitors spent the night inside the structure. "They had a good night and when they came out, they said, 'This was almost like sleeping in a hotel,'" Bergh says. "And the idea was born."

The next year, Bergh explains, was the first that the Icehotel embraced its dual function as a site for art and overnight guests. "There was a lot of trial and error in these years, with what to do and what was possible to do," he says, noting that the hotel evolved from a dormitory-style operation, with several beds per room, to a hotel set on combining adventure and luxury. This year, the Icehotel features 63 rooms, including bedrooms and deluxe suites that feature furniture and even private bathrooms. Though the number of rooms changes each year, the size of the hotel remains the same, occupying almost 60,000 square feet. But throughout its expansion, Icehotel has remained committed to housing original ice art made from the pure water of the Torne.

"My idea was that we should be as close to 100 percent natural as possible," Bergh explains. This hotel should rise out of the river in the early winter, and should return, in the law of nature, back to the river in the springtime. This was our philosophy."

Each year, the Icehotel begins by selecting artists who will build its rooms. Artists from all over the world apply and are selected by a jury panel, which tries to balance veteran sculptors with new, innovative talent. The artists are selected based on their experience, but also on their vision for the project—and how that compares or contrasts to other artists selected for that year. "We don’t accept anything but original art. It has to be original and we never copy, not even ourselves," Bergh says. "It has to be like the cycle of the river, renewed each year."

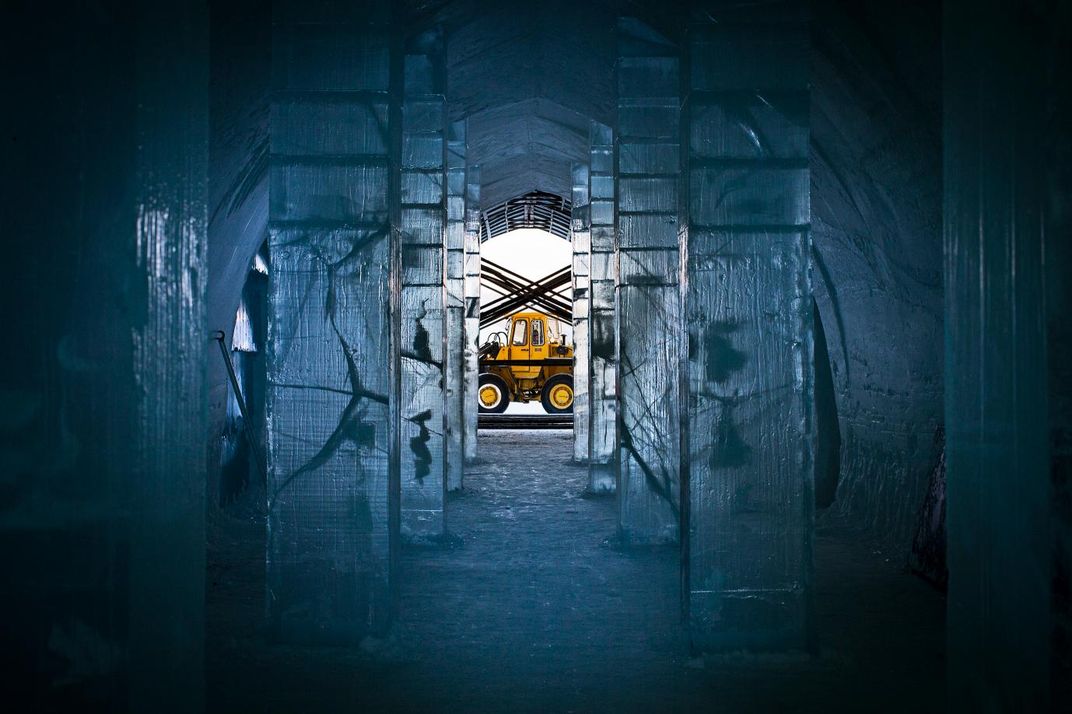

The construction of the hotel's outer skeleton begins in early November, when temperatures in Jukkasjärvi begin to plummet. Through years of trial and error, Icehotel's builders have developed a procedure for creating their own special steel frames, which they pack with snice (a mixture of snow and ice that reflects sunlight, thereby slowing the hotel's eventual melt) and pure ice from the Thorne. The snice and ice are left to harden around steel frames for two days before the frames are removed, leaving behind a shell of ice and snow. When the artists arrive in mid-November, they find all the materials they'll need to complete their rooms and suites, from piles of ice and snice to chisels and irons. Artists also work with light designers to create the perfect light environment for their room (Jukkasjärvi, with its location above the Arctic Circle, experiences near complete darkness during December and January, making artificial light a crucial part of the hotel experience).

The hotel opens to the public in mid-December, and remains open through mid-April. Each season, some 30,000 guests pass through its icy walls, staying an average of two to three nights, according to Bergh. Most will stay one or two nights in the Icehotel itself and pass the rest of their time in separate warm accommodations that surround the ice structure; this warmer housing features about 170 beds as well as two restaurants. During the peak season (before April) the cost to stay a night in the Icehotel ranges from $275 to more than $800, depending on day of the week and the size of the room; the cheapest rooms are relatively plain and aren't designed by artists.

Inside the Icehotel, the temperature remains a chilly 23° Fahrenheit. Guests spend the night on beds made of ice (though the mattress are not, thankfully), wrapped in reindeer pelts and heavy-duty sleeping bags. In the morning, they’re rewarded with hot lingonberry juice and a trip to the sauna, located in an adjacent warm building.

"It's a luxury, but it's a different luxury, because it's the luxury of pure nature and pure art," Bergh explains. "It should be a small adventure to stay in the Icehotel. You should achieve something."

By mid-April, the hotel begins to fall victim to the gradual ascent of the Arctic sun, slowly melting into the land from which it sprung months earlier. The whole process, Bergh explains, is ephemeral, but that's what makes it such an appealing place for artists to experiment and push the boundaries of their ideas. "You can't sell [the ice art], you can’t store it, you can’t put it in a gallery," he says.

The hotel's seasonal existence along the banks of the Torne is more than a temporal constraint for artists and tourists—it's central to the philosophy that drives Icehotel, a philosophy that Bergh feels sets it apart from imitators. "River ice has a life in it. A river is movement," Bergh says. "We pick up the time, the frozen moment, and build an ice hotel. We borrow from nature, and return it in the springtime."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)