The Painstaking Process of Preserving a 400-Pound Blue Whale Heart

This massive specimen is now on display in Canada’s Royal Ontario Museum

:focal(414x380:415x381)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/96/e8964996-f1b7-41eb-ac13-8bb2e4943cab/rom2017_15714_1.jpg)

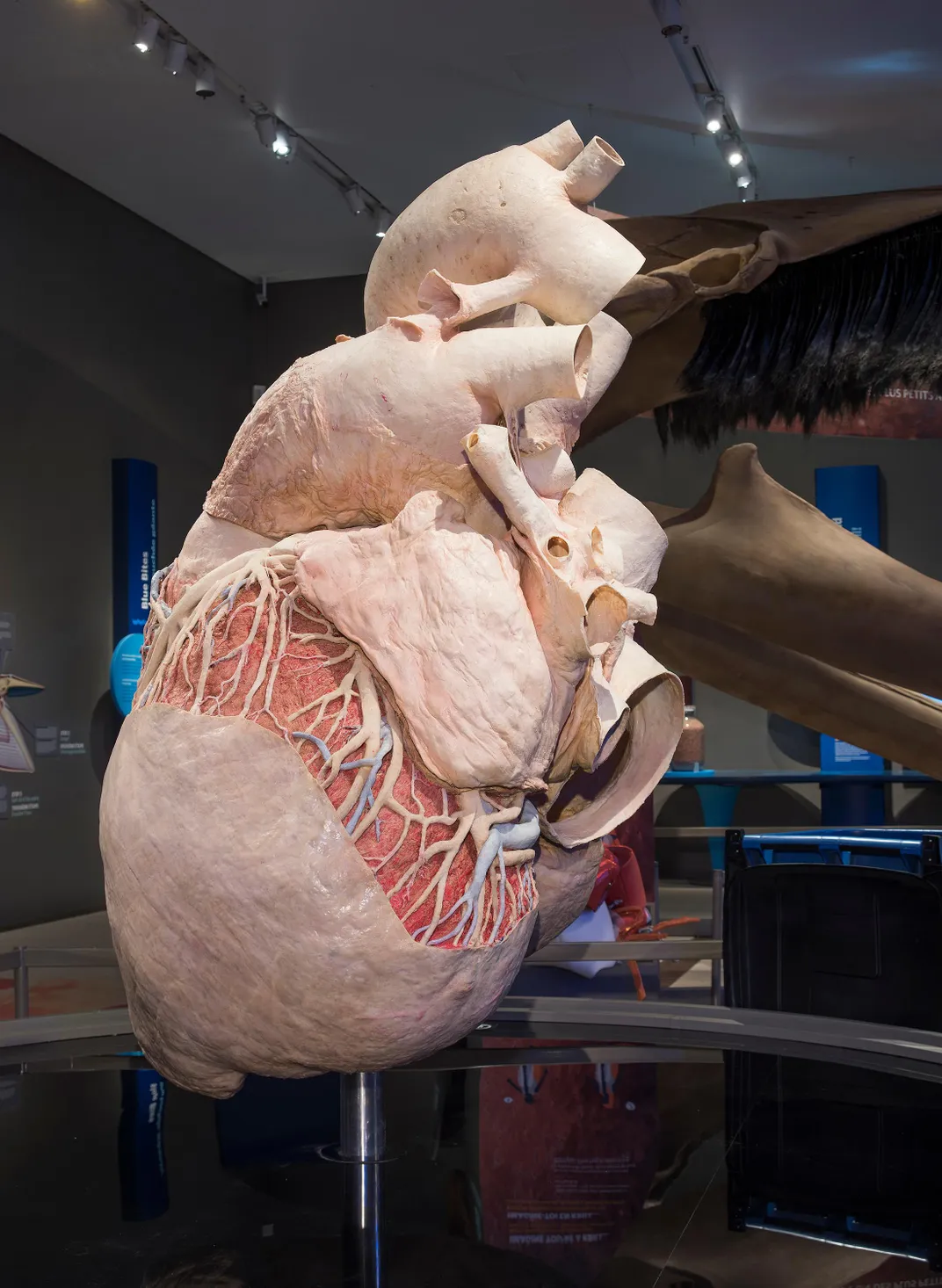

In 2014, the carcass of a female blue whale washed ashore off the coast of Rocky Harbour, a town in western Newfoundland, Canada. The discovery quickly garnered headlines worldwide as locals scrambled to figure out what to do with the massive mammal that suddenly showed up on their doorstep. (It was one of nine blue whales in the area to perish after being trapped in ice—a tragic loss that resulted in a decrease of the species' Northwest Atlantic population by 3 percent.) Now, three years later, that very same whale is making headlines again at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, the first museum in the world to display a fully intact, preserved blue whale heart.

The first thing visitors to the museum will notice when seeing the display, which is part of the exhibition “Out of the Depths: The Blue Whale Story,” is the heart’s sheer size. Blue whales are the largest animals on the planet with gigantic hearts to match. This one in particular weighs nearly 400 pounds and measures approximately six-and-a-half feet in height when its aorta and other greater vessels are taken into account. Once dilated, “it’s large enough to squeeze into a Smart car,” Jacqueline Miller, a mammology technician at ROM, tells Smithsonian.com.

Miller, who helped lead all facets of the project, from acquiring to preserving to installing the heart, worked in Rocky Harbour alongside Brett Crawford of Research Casting International (RCI), a museum technical service that assists in specimen transportation and restoration, to dissect the massive organ from the whale. Although the project would take a full three years from start to finish, the museum knew that putting the heart on display would be an indispensable way for the public to see one up close and understand the sheer magnitude of the animal.

“It took four staff onsite plus myself to push the heart out of the thoracic cavity, through a window created through the ribs and into a dumpster bag,” Miller says.

From there, RCI brought the frozen specimen back to its headquarters in Trenton, Ontario, where it was defrosted. The team, along with veterinarians from Lincoln Memorial University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, used anything they could get their hands on—buckets, bottles, even toilet plungers—to seal every last one of the heart’s cavities before pumping a formaldehyde solution into the heart to prevent decomposition. All told, it took 2,800 liters of the preserving liquid to get the job done. It was now ready for the next stop in its journey: Guben, Brandenburg, Germany.

“We chose to plastinate the heart, employing Gunther Von Hagens' company, Gubener Plastinate GmbH,” Miller says. The famed scientist invented plastination, which is the process of preserving a specimen by replacing its water and fat content with different plastics. (If you’ve ever been to a Body Worlds exhibit, you’ve seen plastinated bodies first hand.)

“We attempted to dilate (inflate) the heart as [much] as possible, as the goal with fixation is two-fold: arrest further decomposition and then to ‘stiffe' the heart as close to its best natural anatomical conformation as possible,” she says. “For us this was diastole; the condition of the heart when it's fully dilated with blood just before it's ejected with a heart contraction to the body. It’s the moment of largest dimensions for the heart.”

On May 16, the plastinated heart arrived in a wooden crate via airplane at Toronto Pearson International Airport before reaching the museum two days later. The heart will be on display now through September 4 along with the skeleton of Blue, a different 80-foot-long blue whale that was also recovered off the coast of Newfoundland three years ago.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/33/a3/33a3e6c5-f3fd-403b-ba58-7e7f04cae14d/rom2015_14517_5_1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/96/e8964996-f1b7-41eb-ac13-8bb2e4943cab/rom2017_15714_1.jpg)