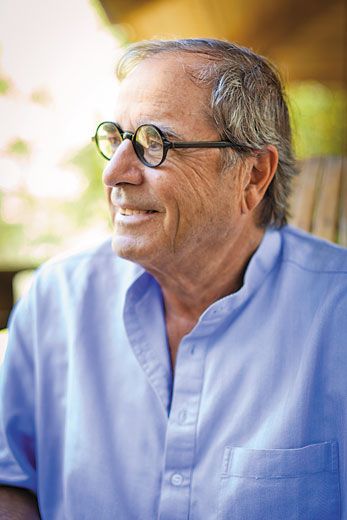

Paul Theroux’s Quest to Define Hawaii

For this renowned travel writer, no place has proved harder to decipher than his home for the past 22 years

Hawaii seems a robust archipelago, a paradise pinned like a bouquet to the middle of the Pacific, fragrant, sniffable and easy of access. But in 50 years of traveling the world, I have found the inner life of these islands to be difficult to penetrate, partly because this is not one place but many, but most of all because of the fragile and floral way in which it is structured. Yet it is my home, and home is always the impossible subject, multilayered and maddening.

Two thousand miles from any great landmass, Hawaii was once utterly unpeopled. Its insularity was its salvation; and then, in installments, the world washed ashore and its Edenic uniqueness was lost in a process of disenchantment. There was first the discovery of Hawaii by Polynesian voyagers, who brought with them their dogs, their plants, their fables, their cosmology, their hierarchies, their rivalries and their predilection for plucking the feathers of birds; the much later barging in of Europeans and their rats and diseases and junk food; the introduction of the mosquito, which brought avian flu and devastated the native birds; the paving over of Honolulu; the bombing of Pearl Harbor; and many hurricanes and tsunamis. Anything but robust, Hawaii is a stark illustration of Proust’s melancholy observation: “The true paradises are the paradises we have lost.”

I think of a simple native plant, the alula, or cabbage plant, which is found only in Hawaii. In maturity, as an eight-foot specimen, you might mistake it for a tall, pale, skinny creature with a cabbage for a head (“cabbage on a stick” is its common description, Brighamia insignis its proper name). In the 1990s an outcrop of it was found growing on a high cliff on the Na Pali Coast in Kauai by some intrepid botanists. A long-tongued moth, a species of hawk moth, its natural pollinator, had gone extinct, and because of this the plant itself was facing extinction. But some rapelling botanists, dangling from ropes, pollinated it with their dabbling fingers; in time, they collected the seeds and germinated them.

Like most of Hawaii’s plants, an early form of the alula was probably carried to the volcanic rock in the ocean in the Paleozoic era as a seed in the feathers of a migratory bird. But the eons altered it, made it milder, more precious, dependent on a single pollinator. That’s the way with flora on remote islands. Plants, so to speak, lose their sense of danger, their survival skills—their thorns and poisons. Isolated, without competition and natural enemies, they become sportive and odder and special—and far more vulnerable to anything new or introduced. Now there are many alula plants—though each one is the result of having been propagated by hand.

This is the precarious fate of much of Hawaii’s flora, and its birds—its native mammals are just two, the Hawaiian hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus semotus), Hawaii’s only native land mammal, and the Hawaiian monk seal (Monachus schauinslandi), both severely endangered and needlessly so. I have seen the slumber of a monk seal on a Hawaii beach interrupted by a dithering dog walker with an unleashed pet, and by onlookers in bathing suits hooting gleefully. There are fewer than 1,100 monk seals in the islands and the numbers are decreasing. The poor creature is undoubtedly doomed.

Hawaii offers peculiar challenges to anyone wishing to write about the place or its people. Of course, many writers do, arriving for a week or so and gushing about the marvelous beaches, the excellent food, the heavenly weather, filling travel pages with holiday hyperbole. Hawaii has a well-deserved reputation as a special set of islands, a place apart, fragrant with blossoms, caressed by trade winds, vibrant with the plucking of ukuleles, effulgent with sunshine spanking the water—see how easy it is? None of this is wrong; but there is more, and it is difficult to find or describe.

I have spent my life on the road waking in a pleasant, or not so pleasant hotel, and setting off every morning after breakfast hoping to discover something new and repeatable, something worth writing about. I think other serious travelers do the same, looking for a story, facing the world, tramping out a book with their feet—a far cry from sitting at a desk and staring mutely at a glowing screen or a blank page. The traveler physically enacts the narrative, chases the story, often becomes part of the story. This is the way most travel narratives happen.

Because of my capacity for listening to strangers’ tales, or the details of their lives, my patience with their food and their crotchets, my curiosity that borders on nosiness, I am told that anyone traveling with me experiences an unbelievable tedium, and this is why I choose to travel alone. Where I have found a place, or its people, to be unyielding I have moved on. But this is a rare happenstance. The wider world in my experience is anything but unyielding. I seldom meet uncooperative people. In traditional societies, especially, I’ve found folks to be hospitable, helpful, talkative, grateful for my interest, and curious about me, too—who I am, where I’m from, and by the way where’s my wife? I have sometimes encountered hostility, but in each case I have found that conflict dramatic enough to write about—a rifle muzzle in my face in Malawi, a predatory shifta bandit in the northern Kenya desert, a pickpocket in Florence, a drunken policeman at a roadblock in rural Angola, a mob in India, teenaged boys jabbing spears at me in a shallow lagoon where I was paddling in Papua New Guinea. Such confrontations go with the territory.

My love for traveling to islands amounts to a pathological condition known as nesomania, an obsession with islands. This craze seems reasonable to me, because islands are small self-contained worlds that can help us understand larger ones. For example, in Easter Island, Earth Island, the authors Paul Bahn and John Flenley convincingly argue that the fate of the world has been prefigured by the eco-disaster of Easter Island, the history of this small rock standing as a parable of the earth. Literature is full of island parables too, from The Tempest through Robinson Crusoe to Lord of the Flies, and notably in each case the drama arises from people who have arrived on the island from the outside world.

One of the traits that I’ve found in many island cultures is a deep suspicion of the outsiders, palangi, as such people are called in Samoa, suggesting they’ve dropped from the sky; a haole in Hawaii, meaning “of another breath”; the “wash-ashore” as non-islanders are dismissively termed in Martha’s Vineyard and other islands. Of course it’s understandable that an islander would regard a visitor with a degree of suspicion. An island is a fixed and finite piece of geography, and usually the whole place has been carved up and claimed. It is inconceivable that a newcomer, invariably superfluous, could bring a benefit to such a place; suspicion seems justified. The very presence of the visitor, the new arrival, the settler, suggests self-interest and scheming.

“They will break your boat!” an islander howled at me in Samoa, when I met him on a path near the beach and told him I had paddled there. “Or the boys will steal it!”

“Why would they do that?”

“Because you’re a palangi and you’re alone. You have no family here. Let’s go—I’ll help you.”

It was true: A gang of boys was lurking near my kayak drawn up on the beach, looking eager (and the man confirmed this) to kick it to pieces. Because I didn’t belong there, because I had no connection, no friend, except this man who took pity on me and volunteered to warn me to go away.

At the time I assumed I was one against the many, and that the islanders were unified, with a common consciousness that caused them to oppose the arrival of a palangi. Perhaps this was so, though Robert Louis Stevenson, resident in Samoa, wrote a whole book about Samoan civil war, A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa. I was well aware when writing a travel book about Pacific islands that, because I had no friends or relations on shore, I was never truly welcomed in any set of islands. At best, the islanders were simply putting up with me, waiting for me to paddle away.

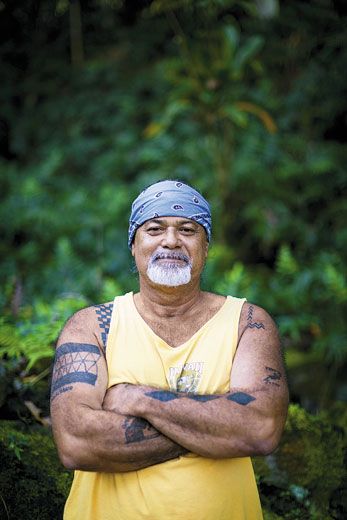

These were mostly islands with a single culture and language. They were not xenophobic but rather suspicious or lacking in interest. Hawaii is another story, a set of islands with a highly diverse ethnicity, ranging from the Hawaiians who refer to themselves as kanaka maoli (original people), whose ancestry goes back 1,500 years (some say 2,000), to people who arrived just the other day. But the mainland United States can be described that way, too—many Native Americans can claim a pedigree of 10,000 years.

I have lived in Hawaii for 22 years, and in this time have also traveled the world, writing books and articles about Africa, Asia, South America, the Mediterranean, India and elsewhere. Though I have written a number of fictional pieces, including a novel, Hotel Honolulu, set in Hawaii, I have struggled as though against monster surf to write nonfiction about the islands. I seldom read anything that accurately portrayed in an analytical way the place in which I have chosen to live. I have been in Hawaii longer than anywhere else in my life. I’d hate to die here, I murmured to myself in Africa, Asia and Britain. But I wouldn’t mind dying in Hawaii, which means I like living here.

Some years ago, I spent six months attempting to write an in-depth piece for a magazine describing how Hawaiian culture is passed from one generation to the other. I wrote the story, after a fashion, but the real tale was how difficult it was to get anyone to talk to me. I went to a charter school on the Big Island, in which the Hawaiian language was used exclusively, though everyone at the place was bilingual. Aware of the protocol, I gained an introduction from the headmaster of the adjoining school. After witnessing the morning assembly where a chant was offered, and a prayer, and a stirring song, I approached a teacher and asked if she would share with me a translation of the Hawaiian words I had just heard. She said she’d have to ask a higher authority. Never mind the translation, I said; couldn’t she just write down the Hawaiian versions?

“We have to go through the proper channels,” she said.

That was fine with me, but in the end permission to know the words was refused. I appealed to a Hawaiian language specialist, Hawaiian himself, who had been instrumental in the establishment of such Hawaiian language immersion schools. He did not answer my calls or messages, and in the end, when I pressed him, he left me with a testy, not to say xenophobic, reply.

I attended a hula performance. Allusive and sinuous, it cast a spell on me and on all the people watching, who were misty-eyed with admiration. When it was over I asked the kumu hula, the elder woman who had taught the dancers, if I could ask her some questions.

She said no. When I explained that I was writing about the process by which Hawaiian tradition was passed on, she merely shrugged. I persisted mildly and her last and scornful words to me were, “I don’t talk to writers.”

“You need an introduction,” I was told.

I secured an introduction from an important island figure, and I managed a few interviews. One sneeringly reminded me that she would not have bestirred herself to see me had it not been for the intervention of this prominent man. Another gave me truculent answers. Several expressed the wish to be paid for talking to me, and when I said it was out of the question they became stammeringly monosyllabic.

Observing protocol, I had turned up at each interview carrying a present—a large jar of honey from my own beehives on the North Shore of Oahu. No one expressed an interest in the origin of the honey (locally produced honey is unusually efficacious as a homeopathic remedy). No one asked where I was from or anything about me. It so happened that I had arrived from my house in Hawaii, but I might have come from Montana: No one asked or cared. They did not so much answer as endure my questions.

Much later, hearing that I had beehives, some Hawaiians about to set off on a canoe voyage asked if I would give them 60 pounds of my honey to use as presents on distant Pacific islands they planned to visit. I supplied the honey, mildly expressing a wish to board the canoe and perhaps accompany them on a day run. Silence was their stern reply: And I took this to mean that though my honey was local, I was not.

I was not dismayed: I was fascinated. I had never in my traveling or writing life come across people so unwilling to share their experiences. Here I was living in a place most people thought of as Happyland, when in fact it was an archipelago with a social structure that was more complex than any I had ever encountered—beyond Asiatic. One conclusion I reached was that in Hawaii, unlike any other place I had written about, people believed that their personal stories were their own, not to be shared, certainly not to be retold by someone else. Virtually everywhere else people were eager to share their stories, and their candor and hospitality had made it possible for me to live my life as a travel writer.

Obviously, the most circumscribed islanders are the Hawaiians, numerous because of the one-drop rule. Some people who regarded themselves before statehood, in 1959, as of Portuguese or Chinese or Filipino descent, identified themselves as Hawaiian when sovereignty became an issue in the later 1960s and ’70s and their drop of blood gave them access. But there are 40 or more contending Hawaiian sovereignty groups, from the most traditional, who worship deities such as Pele, “She-who-shapes-the-land,” goddess of volcanoes, through the Hawaiian hymn singers in the multitude of Christian churches, to the Hawaiian Mormons, who believe, contrary to all serious Pacific scholarship and the evidence of DNA testing, that mainlanders (proto-Polynesians) got to Hawaii from the coast of the Land of Joshua (now California) when Hagoth the Mormon voyager (Book of Mormon, Alma 63:5-8) sailed into the West Sea and peopled it.

But it wasn’t just native Hawaiians who denied me access or rebuffed me. I began to see that the whole of Hawaii is secretive and separated, socially, spacially, ethnically, philosophically, academically. Even the University of Hawaii is insular and uninviting, a place unto itself, with little influence in the wider community and no public voice—no commentator, explainer, nothing in the way of intellectual intervention or mediation. It is like a silent and rather forbidding island, and though it regularly puts on plays and occasionally a public lecture, it is in general an inward-looking institution, esteemed locally not for its scholarship but for its sports teams.

As a regular user of the UH library, researching my Tao of Travel I requested some essential books from the library system that happened to be located on a neighbor island.

“You are not on the faculty,” I was told by one of the desk functionaries in a philistine’s who-might-you-be-little-man? tone. “You are not a student. You are not allowed to borrow these books.”

It made no difference that I am a writer, because apart from my library card—a UH Community Card that costs me $60 a year—I had no credibility at the university, even though my own 40-odd books occupy its library shelves. Books may matter, but a writer in Hawaii is little more than a screwball or an irritant, with no status.

Pondering this odd separation, I thought how the transformative effects of island existence are illustrated in humans as well as in plants, like the alula that had become cut off and vulnerable. Island life is a continuous process of isolation and endangerment. Native plants became hypersensitive and fragile, and many alien species have a tendency to assault and overwhelm this fragility. The transformation was perhaps true of people, too—that the very fact that a person was resident on an island, with no wish to leave, he or she was isolated in the precise etymological meaning of the word: “made into an island,” alone, separated, set apart.

In an archipelago of multiethnicity the trend to apartness is not a simple maneuver. To emphasize separation, the islander created his own metaphorical island, based on race, ethnicity, social class, religion, neighborhood, net worth and many other factors; islands upon islands. Over time I have begun to notice how little these separate entities interact, how closed they are, how little they overlap, how naturally suspicious and incurious they are, how each one seems to talk only to itself.

“I haven’t been there for 30 years,” people say about a part of the island ten miles away. I have met born-and-bred residents of Oahu who have been to perhaps one neighbor island, and many who have never been to any—though they may have been to Las Vegas.

“We sent a large group of musicians and dancers from Waianae to the Edinburgh Festival,” a civic-minded and philanthropic woman told me recently. “They were a huge hit.”

We were speaking in the upscale enclave of Kahala. The obvious irony was that it was possible, as I suggested to the woman, that the Waianae students who had gone across the world to sing had probably never sung in Kahala, or perhaps even been there. Nor do the well-heeled Kahala residents travel to hard-up Waianae.

It is as though living on the limited terra firma of an island inspires groups to recreate their own island-like space, as the Elks and the other clubs were exclusive islands in the segregated past. Each church, each valley, each ethnic group, each neighborhood is insular—not only Kahala, or the equally salubrious Diamond Head neighborhood, but the more modest ones too. Leeward Oahu, the community of Waianae, is like a remote and somewhat menacing island.

Each of these notional islands has a stereotypical identity; and so do the actual islands—a person from Kauai would insist that he or she is quite unlike someone from Maui, and could recite a lengthy genealogy to prove it. The military camps at Schofield and Kaneohe and Hickam and elsewhere exist as islands, and no one looks lonelier on a Hawaii beach than a jarhead, pale, reflective, perhaps contemplating yet another deployment to Afghanistan. When the George Clooney film The Descendants was shown on the mainland, it baffled some moviegoers because it did not depict the holiday Hawaii that most people recognize—and where were Waikiki and the surfers and the mai tais at sunset? But this film was easily understood by people in Hawaii as the story of old-timers here, so-called keiki o ka aina—children of the islands, and many of them haole, white. They have their metaphorical island—indeed, one keiki o ka aina family, the Robinsons, actually owns its own island, Niihau, off the coast of Kauai, with a small resident population of Hawaiians, where off-islanders are generally forbidden to go.

Even the water is circumscribed. Surfers are among the most territorial of Hawaii residents. Some of them deny this, and say that if certain deferential rules of politeness are observed (“You take dis wave, brah,” a recently arrived surfer calls out to humble himself in the lineup), it is possible to find a measure of mutual respect and coexistence. But much of this is basic primate behavior, and most of the surfers I have met roll their eyes and tell me that the usual response to a newcomer is, “Get off my wave!”

All this was a novelty to me, and a lesson in that nebulous genre known as travel writing. As a traveler, I had become used to strolling confidently into the oddest places—approaching a village, a district, a slum, a shantytown, a neighborhood—and, observing the dress code, the niceties, the protocol, asking frank questions. I might be inquiring about a person’s job, or lack of employment, their children, their family, their income; I nearly always got a polite answer. Recently in Africa I made a tour of the townships of Cape Town, not just the bungalows, the dusty dwellings, the temporary shelters and hostels, but the shacks and squatter camps, too. My questions were answered: It is how the traveler acquires information for the narrative.

In the worst slum in India, the meanest street in Thailand or Cambodia, chances are that a smile will make you welcome; and if you have a smattering of Portuguese or Spanish, you will probably have your questions answered in a Brazilian favela or an Angolan musseque, or an Ecuadorean barrio, in each case a shantytown.

So why are islands so different, and why is a place like Hawaii—one of the 50 United States—so uncooperative, so complex in its division? This, after all, is a state in which following the attack on Pearl Harbor, more than 3,000 men from Hawaii, all of Japanese ancestry, volunteered to fight, and their unit, the 442nd Infantry, became the most decorated regiment in U.S. history, with 21 Medals of Honor. But that was the Army, and that was in Europe.

First of all, what looks in Hawaii like hostility is justifiable wariness, with an underlying intention to keep the peace. Confrontation is traumatic in any island society, because, while there is enough room for mutual coexistence, there is not enough space for all-out war. Just such a disruptive conflict got out of hand and destroyed the serenity of Easter Island, reducing its population, upending its brooding statues and leaving a legacy of blood feud among the clans. Fiji went to war with itself, so did Cyprus, with disastrous results. Hawaii, to its credit, and its survival, tends to value the obliqueness and nonconfrontation and suspension of disbelief that is embodied in the simple word “aloha,” a greeting for gently keeping people mellow. (What I am doing now, taking an unmellow look at Hawaii, is regarded locally as heresy.)

So perhaps a reason for Hawaii’s tendency to live in specific zones is a conscious survival strategy as well as a mode of pacification. Fearing disharmony, knowing how conflict would sink the islands, Hawaiians cling to the mollifying concept of aloha, a Hawaiian word that suggests the breath of love and peace.

In spite of its divisions, Hawaii is united, and perhaps more like-minded than any islander admits. Each self-regarding metaphorical island has an unselfish love for the larger island, as well as a pride in its brilliant weather, its sports, its local heroes (musicians, athletes, actors). Another unifier is the transcending style of hula—danced by kanaka maoli and haole alike; and hula is aloha in action. Just about everyone in Hawaii agrees that if the spirit of aloha remains the prevailing philosophy, it will bring harmony. “Aloha” is not a hug, it is meant to disarm. More and more I have come to see this subtle greeting, a word uttered with a floating ambiguous smile, as less a word of welcome than a means of propitiating a stranger. But perhaps all words of welcome perform that function.

As for the fanciful assertion of largeness, it is reassuring for an islander to know that the Big Island is big, as well as multidimensional, and to maintain the belief that much of Hawaii is hidden and undiscovered. It helps, if you want to cherish the idea of distance and mystery, that you do not stray far from home, your very own metaphorical island.

Further defining the zones of separation is the bumpy and jagged topography of a volcanic island, its steep valleys, its bays and cliffs and plains, its many elevations. In Hawaii there’s also a palpable difference in weather from one place to another, the existence of microclimates that underline the character of a place. I can drive 20 miles in one direction to a much drier part of the island, 20 miles in another to a place where it is probably raining, and in between it might be 12 degrees cooler. The people in those spots seem different, too, taking on the mood of their microclimate.

Nevermind that Hawaii is seven inhabited islands; even on relatively smallish Oahu—about 50 miles across—there are many places that are considered remote. This whimsy of distance enlarges the island and inspires the illusion of a vast hinterland, as well as the promise of later discovery. I am bemused by the writer from the mainland who, after five days of gallivanting and gourmandizing, is able to sum up Hawaii in a sentence or two. I was that person once. These days, I am still trying to make sense of it all, but the longer I live here the more the mystery deepens.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.