Save the Sharks By Swimming With Them

Ecotourism is helping promote shark conservation around the world—while also boosting local economies.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/12/7f12ec1d-569a-4c1a-821e-2a3bc6c66f43/image.jpeg)

Every year, as many as 100 million sharks meet their demise at the hands of humans. Many die mutilated in the ocean as their fins, hacked from their bodies, sail away to foreign markets, where they fetch prices as high as $500 per pound. Sharks are especially vulnerable to population decreases due to their slow growth rate and low birth numbers, and overfishing and finning has left one-third of open ocean sharks at the brink of extinction. But it turns out that this unsustainable practice is more than just harmful for sharks and the ecosystems they support—it's bad economic sense for humans, too.

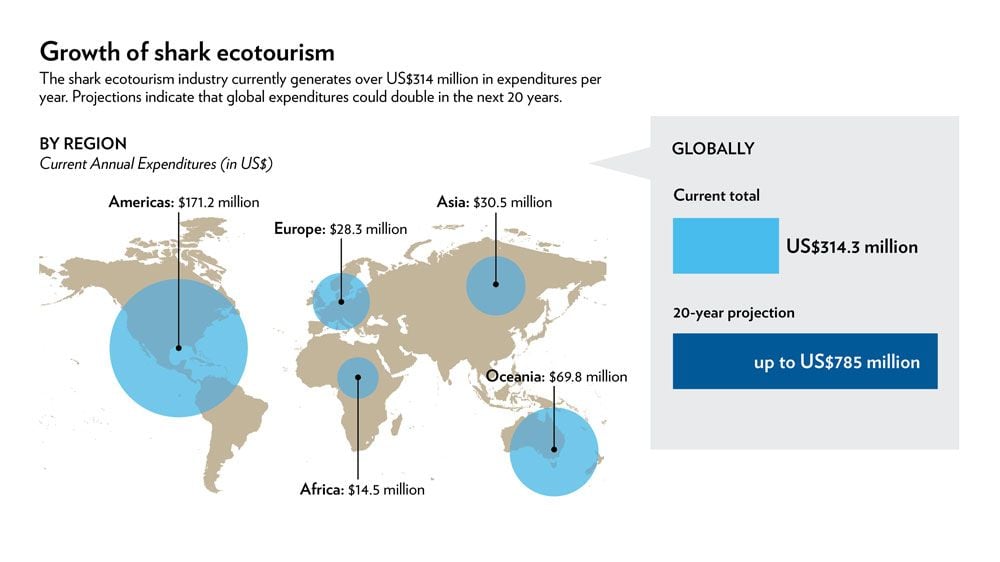

In May 2013, a group of researchers from the University of British Columbia published a paper studying the economic benefits of the shark fin trade versus the emerging shark tourism industry. They found that while global shark fisheries earn around $630 million annually, the numbers have been in decline for the past decade. Shark tourism, on the other hand, earns $314 million annually—and that industry is expected to keep growing, raking in a potential $780 million annually over the next 20 years. For instance, a study published August 12 in the journal PeerJ shows that whale shark tourism contributes $20 million dollars annually to the economy of the Maldives.

"Sharks are worth more alive," says Angelo Villagomez, manager of the Pew Charitable Trusts' global shark conservation campaign. "Sharks are fished because they have value in fisheries, but a lot of tropical island locations, especially holiday destinations, have found that they can get a lot more out of their resources with dive tourism."

One place that has had great success in transitioning from a fishing-based economy to a tourism economy is Isla Mujeres, near Cancun, Mexico. "Instead of selling a fish, if you bring people to snorkel with that fish, you can make a sustainable living off of the life of the animal," explains John Vater, head of Ceviche Tours, a company based out of Isla Mujeres. Founded in 2007, Vater's company is committed to sustainable shark tourism, using Isla Mujeres' location as part of the world's second largest barrier reef system to promote shark education and conservation. Swimming with whale sharks around Isla Mujeres, which attracts large schools of the massive fish each year due to high plankton populations, has been a huge economic boost for an area with few other economic options. "Tourism is really the only product that Isla Mujeres has to sell," Vater says. "It has really helped the families of Isla Mujeres and the surrounding areas of the Yucatan."

In response to their success in Isla Mujeres, Vater and the company decided to start an annual Whale Shark Festival, which has taken place during the month of July for the past seven years. Beyond offering visitors a chance to swim with whale sharks, the festival gives Vater and others an international platform to talk about the importance of conservation. "The reverence for the fishes and marine environment has really, really grown," he says.

Isla Mujeres isn't the only place to learn that sharks can be more valuable in the water than at a market. Since 1998, the World Wildlife Fund has been working to set up a sustainable shark tourism program in the coastal town of Donsol, in the Philippines about 280 miles southeast of the capital Manila. When video footage from an amateur diver revealed a high population of whale sharks swimming off Donsol's coast, conservationists and locals embarked on a first-of-its-kind preservation effort, hoping to use the fish to help boost Donsol's economy. Today, with the help of a holistic conservation approach that includes tagging and satellite monitoring, Donsol rakes in the equivalent of roughly $5 million U.S., all from shark tourism. "After a decade, revenues from eco-tourism transformed the once-sleepy village into one of the region's top tourist draws. Donsol is the perfect example of how stewarding resources generates revenue," explains Gregg Yan, head of WWF-Philippines Communications. "In turn, this uplifts local economies to holistically improve people's lives."

If you're interested in shark tourism, it's important to do some due diligence before selecting a location and tour provider. In the eyes of some conservationists, the practice has earned a bad reputation, mainly due to tours that feed the sharks to attract them. Opponents argue that feedings run the risk of changing shark behavior, discouraging the fish from following normal migration patterns and conditioning them to find food in tourist areas. But at least one study runs counter to these expectations: the 2012 study, conducted by researchers at the University of Miami, looked at sharks in the Bahamas, where shark tourism and feeding exists, and Florida, where feeding is forbidden. They found that sharks in the Bahamas actually traveled further distances than the sharks in Florida. Still, shark tourism is something to support only if it is done sustainably, cautions Yan.

"Not only should [tourists] be conscious that the divers are operating under best practices, but they should think about spending their money in countries that are taking the time to protect their sharks and other animals," Villagomez says. Choose to visit a place with a dedicated shark sanctuary, which means that the country has taken policy measures to ensure shark conservation. Villagomez suggests taking a trip to Palau, which became the first place in the world to create a shark sanctuary in 2009. Tourists who swim with sharks within the sanctuary pay a number of taxes, which are funneled back into conservation and the local economy. The high fees also help control the number of tourists. "It’s not perfect, but they’re taking steps in the right direction," Villagomez says.

Most shark tourism continues to focus on whale sharks, not only because they're the largest fish in the ocean. Whale sharks are relatively slow moving and are filter feeders that tend to swim close to the water's surface slurping up plankton, making them relatively easy and safe to dive with. Other species of shark, however, have also helped boost local tourism economies worldwide: since great white sharks have been spotted off the coast of New England, for example, towns throughout Cape Cod have noticed an uptick in shark-related tourism, though those visitors aren't necessarily clamoring to dive into the water.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)