Searching for Hanoi’s Ultimate Pho

With more Americans sampling Vietnam’s savory soup, a noted food critic and an esteemed maestro track down the city’s best

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Pho-served-Spice-Garden-buffet-631.jpg)

The New York Philharmonic orchestra opened its historic first concert in Hanoi this past October with a lilting rendition of the Vietnamese national anthem, Quoc ca Viet Nam (“Armies of Vietnam, Forward”), followed by the more spirited strains of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Standing at attention for both in an atmosphere that can only be described as electric, the audience of fashionably dressed Vietnamese and a few Americans could hardly fail to sense both irony and respect as the once-bitter adversaries came together in the grandiose Hanoi Opera House built by the French in 1911.

Alan Gilbert, the Philharmonic’s new music director, was later asked what he had been thinking as he was conducting. “Well, of course, getting it right for a pretty big moment,” he said. “But also, I have to admit, there were a few mental flashes of pho.”

For three days, Gilbert and I, separately and together, had scoured dozens of stalls lining both the broad avenues and the tight back alleys of Hanoi, seeking out versions of the lusty beef noodle soup that is Vietnam’s national dish. We were joined intermittently by various orchestra members, including Gilbert’s Japanese-born mother, Yoko Takebe, who has been a violinist with the Philharmonic for many years (as was his father, Michael Gilbert, until he retired in 2001). Between dodging motorbikes and cars that streamed unimpeded by stoplights—an amenity missing from the burgeoning capital—we slurped bowl after bowl of Vietnam’s answer to Japan’s ramen and China’s lo mein.

In his travels, the 43-year-old maestro has become quite a food buff. When I learned that he planned to spend time between rehearsals and master classes seeking authentic pho on its native turf, I asked to tag along. Both of us were aware of the culinary rage pho has lately become in the United States, as Vietnamese restaurants flourish across the country—especially in Texas, Louisiana, California, New York and in and around Washington, D.C. The noodle-filled comfort food seems well suited to the current economy. (In the United States, you can get a bowl of pho for $4 to $9.) As a food writer, I’ve had an enduring obsession with food searches. They have taken me to obscure outposts, led to lasting friendships around the world and immersed me in local history and social customs.

And so it proved with pho, as Gilbert and I went about this throbbing, entrepreneurial city, admiring restored early-20th-century architectural landmarks built during the French protectorate, when the country was called Tonkin and the region was known as Indochina. Gilbert willingly agreed to an ambitious itinerary, which we punctuated with dueling wordplay—“Phobia,” “It’s what’s pho dinner,” “pho pas”— as we sought out the most authentic, beef-based pho bo or the lighter, chicken-based pho ga. Alas, our puns were based on the incorrect American pronunciation, “foe.” In Vietnamese, it is somewhere between “fuh” and “few,” almost like the French feu, for fire, as in pot-au-feu, and thereby hangs a savory shred of history.

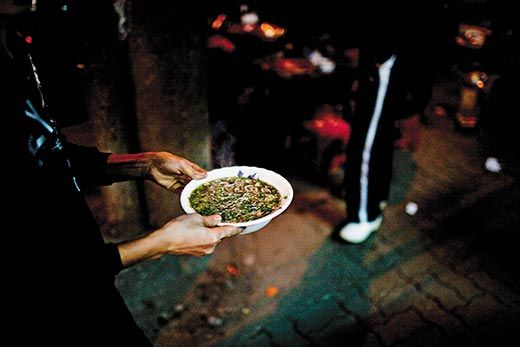

We chopsticked our way through slim and slippery white rice noodles, green and leafy tangles of Asian basil, sawtooth coriander, peppermint, chives and fern-like cresses. For pho bo, we submerged slivers of rosy raw beef in the scalding soup to cook just milliseconds before we consumed them. Pho ga, we discovered, is traditionally enriched with a raw egg yolk that ribbons out as it coddles in the hot soup. Both chicken and beef varieties were variously aromatic, with crisp, dry-roasted shallots and ginger, exotically subtle cinnamon and star anise, stingingly hot chilies, astringent lime or lemon juice and nuoc mam, the dark, fermented salty fish sauce that tastes, fortunately, better than it smells. It is that contrast of seasonings—sweet and spicy, salty, sour and bitter, hot and cool—that makes this simple soup so intriguing to the palate.

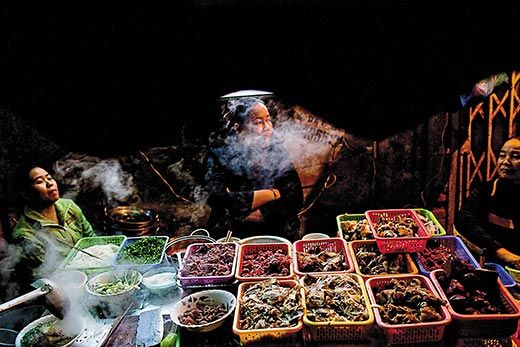

Gilbert gamely confronted bare, open-front pho stalls that had all the charm of abandoned carwashes and lowered his broad, 6-foot-1 frame onto tiny plastic stools that looked like overturned mop buckets. Nor was he fazed by the suspiciously unhygienic makeshift “kitchens” presided over by chatty, welcoming women who stooped over charcoal or propane burners as they reached into pots and sieves and balanced ladles of ingredients before portioning them into bowls.

In planning this adventure, I had found my way to the Web site of Didier Corlou (www.didiercorlou.com). A chef from Brittany who trained in France, he has cooked in many parts of the world and, having lived in Hanoi for the past 19 years, has become a historian of Vietnamese cuisine and its long-neglected native spices and herbs. Corlou and his wife, Mai, who is Vietnamese, run La Verticale, a casually stylish restaurant where he applies French finesse to traditional Vietnamese dishes and ingredients. I spent my first morning in Hanoi learning the ins and outs of pho while sipping Vietnamese coffee—a seductively sweet iced drink based on strong locally grown, French-brewed coffee beans and, improbably, syrupy canned condensed milk—in Corlou’s fragrant, shelf-lined shop, where he sells customized spice blends. The shop provides entry to the restaurant.

Chef Corlou regards Vietnamese cuisine as one of the most original and interesting he has experienced; he values its ingenuity with humble products, its emphasis on freshness, the counterplay of flavors and the harmonious fusion of foreign influences, most notably from China and France. The pho we know today, he told me, began as a soup in and around Hanoi just a little over 100 years ago. “It is the single most important dish,” he said, “because it is the basic meal of the people.”

Pho bo is an unintended legacy of the French, who occupied Vietnam from 1858 to 1954 and who indeed cooked pot-au-feu, a soup-based combination of vegetables and beef, a meat barely known in Vietnam in those days and, to this day, neither as abundant nor as good as the native pork. (Corlou imports his beef from Australia.) But just as North American slaves took the leavings of kitchens to create what we now celebrate as soul food, so the Vietnamese salvaged leftovers from French kitchens and discovered that slow cooking was the best way to extract the most flavor and nourishment from them. They adopted the French word feu, just as they took the name of the French sandwich loaf, pain de mie, for banh mi, a baguette they fill with various greens, spices, herbs, sauces, pork and meatballs. Vietnam is perhaps the only country in the Far East to bake Western-style bread.

“The most important part of the pho is the broth,” Corlou said, “and because it takes so long to cook, it’s difficult to make at home. You need strong bones and meat—oxtail and marrow-filled shinbones—and before being cooked they should be blanched and rinsed so the soup will be very clear. And you must not skim off all of the fat. Some is needed for flavor.”

The cooking should be done at an almost imperceptible simmer, or what cooks sometimes describe as a “smile.” (One instruction advises that the soup simmer overnight for at least 12 hours, with the cook staying awake to add water lest the broth reduce too much.) Only then does one pay attention to the width (about a quarter-inch) of the flat, silky rice noodles, and to the combination of greens, the freshness of the beef and, finally, to the golden-brown knots of fried bread, all added just moments before the pho is served. Despite his stringent rules, Corlou is not against the variations of pho that come with distance from Hanoi; in Saigon, far to the south, it’s closer to the pho usually found in the United States, sweetened with rock sugar and full of mung bean sprouts and herbs, both rarely seen in the north.

A tasting dinner that night at La Verticale included Philharmonic president Zarin Mehta and his wife, Carmen; Gilbert and his mother; pianist Emanuel Ax; and Eric Latzky, the orchestra’s director of communications. We were served about a dozen French-Vietnamese creations, including two haute phos, a rather mild one based on salmon with an astringent hint of coriander and another enriched with superb local foie gras, black mushrooms and crunchy cabbage.

The next day, Corlou guided a group of us through the teeming, winding aisles of the Hang Be market, close to willow-rimmed Hoan Kiem Lake, a habitat of Sunday strollers and early-morning practitioners of tai chi. He pointed out various fruits—among them seed-filled dragon fruit and russet, spiky-skinned rambutans—and introduced us to banana flowers, the pale mauve blossoms and creamy-white slivers of trunk shaved from newly sprouted banana trees. Dark gray, spotted snake-like fish swam in tanks, hard-shelled crabs writhed in their boxes, slices of pork sausages sizzled on grills and live rabbits and chickens plotted escapes from their cages. As lunchtime neared, market workers stretched out on cloths they draped over crates and mounds of produce and snoozed, their conical straw hats shielding their faces from light and flies. Hanging over all was the almost stifling fragrance of ripe tropical fruit, cut flowers and pungent spices, sharpened by the nose-twitching scents of nuoc mam sauce and medicinally sour-sweet lemon grass.

I sought pho recommendations from United States Ambassador Michael W. Michalak and his wife, Yoshiko. During a reception for the orchestra at the U.S. Embassy, a villa in the 20th-century palatial style, they introduced us to Do Thanh Huong, a local pho buff who owns two fashion gift shops named Tan My. With her recommendations added to Corlou’s, we expected easy success in our forays, and, when it came to pho ga, we had no problems.

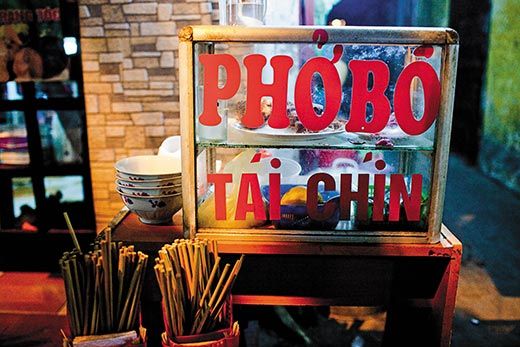

But looking for pho bo at midday proved a mistake. Hungrier by the minute, we searched out such recommended pho redoubts as Pho Bo Ly Beo, Pho Bat Dan, Pho Oanh and Hang Var, only to find each shuttered tight. Thus we learned the hard way that the beefy broth is traditionally a breakfast or late-night dish, with shops opening between 6 and 8 a.m. and again around 9 or 10 at night.

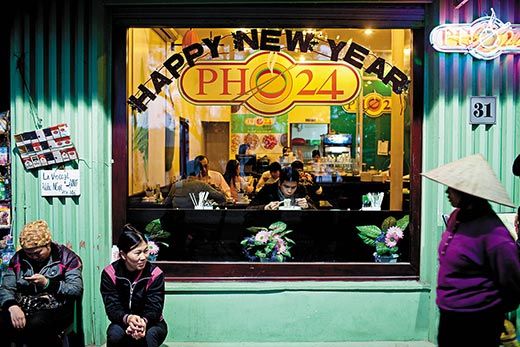

The next day, Gilbert and I were disappointed by a pallid, salty and inept pho bo at a much-recommended branch of a slick, trendy Saigon chain, Pho24; we dubbed it McPho. For the rest of our days in Hanoi, we rose early to find excellent pho in the stalls that had been closed to us at lunch. We also discovered Spices Garden, a very good Vietnamese restaurant in the restored Sofitel Metropole Hanoi, the historic hotel once patronized by Graham Greene, W. Somerset Maugham and Charlie Chaplin. There a verdant, abundant pho bo is part of the lunchtime buffet (no surprise, since Didier Corlou was the chef at the hotel for 16 years, until 2007). On the second and final night of the Philharmonic’s engagement, the audience included a large number of children whose parents had brought them to hear the Brahms Concerto in D major for Violin and Orchestra, with featured violinist Frank Peter Zimmermann. Tetsuji Honna, the Japanese music director of the Vietnam National Symphony Orchestra, explained to me that the violin is the most popular instrument for children in Asia to learn.

After the concert, Honna and one of his violinists, Dao Hai Thanh, invited me to try some late-night pho in the old quarter of Hanoi around Tong Duy Tan Street. Here young Vietnamese gather at long tables at a variety of stalls where meats and vegetables are cooked over table grills or dipped into hot pots of seething broth.

Our destination was Chuyen Bo, a pho stall with stools so low that Honna had to pile three atop one another for me to sit on. The choice of ingredients was staggering: not only eight kinds of greens, tofu, soft or crisp noodles, but also various cuts of beef—oxtail, brisket, shoulder, kidneys, stomach, tripe, lungs, brains—plus cooked blood that resembled blocks of chocolate pudding, a pale pink meat described to me as “cow’s breast” (finally decoded as “udder”) and a rather dry, sinewy-looking meat that one of the workers, pointing to his groin, said was “from a man.” I was relieved to learn that the ingredient in question was a bull’s penis. I opted instead for a delicious if conventional pho of oxtail and brisket. But later I worried that I had missed an opportunity. Perhaps udder and penis pho might have made a more stirring, not to mention memorable, finale to my quest. Maybe next time. Pho better or pho worse.

Mimi Sheraton has been a food writer for over 50 years. She has written more than a dozen books, including the 2004 memoir Eating My Words: An Appetite for Life.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.