Sleeping with Cannibals

Our intrepid reporter gets up close and personal with New Guinea natives who say they still eat their fellow tribesmen

For days I've been slogging through a rain-soaked jungle in Indonesian New Guinea, on a quest to visit members of the Korowai tribe, among the last people on earth to practice cannibalism. Soon after first light this morning I boarded a pirogue, a canoe hacked out of a tree trunk, for the last stage of the journey, along the twisting Ndeiram Kabur River. Now the four paddlers bend their backs with vigor, knowing we will soon make camp for the night.

My guide, Kornelius Kembaren, has traveled among the Korowai for 13 years. But even he has never been this far upriver, because, he says, some Korowai threaten to kill outsiders who enter their territory. Some clans are said to fear those of us with pale skin, and Kembaren says many Korowai have never laid eyes on a white person. They call outsiders laleo ("ghost-demons").

Suddenly, screams erupt from around the bend. Moments later, I see a throng of naked men brandishing bows and arrows on the riverbank. Kembaren murmurs to the boatmen to stop paddling. "They're ordering us to come to their side of the river," he whispers to me. "It looks bad, but we can't escape. They'd quickly catch us if we tried."

As the tribesmen's uproar bangs at my ears, our pirogue glides toward the far side of the river. "We don't want to hurt you," Kembaren shouts in Bahasa Indonesia, which one of our boatmen translates into Korowai. "We come in peace." Then two tribesmen slip into a pirogue and start paddling toward us. As they near, I see that their arrows are barbed. "Keep calm," Kembaren says softly.

Cannibalism was practiced among prehistoric human beings, and it lingered into the 19th century in some isolated South Pacific cultures, notably in Fiji. But today the Korowai are among the very few tribes believed to eat human flesh. They live about 100 miles inland from the Arafura Sea, which is where Michael Rockefeller, a son of then-New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, disappeared in 1961 while collecting artifacts from another Papuan tribe; his body was never found. Most Korowai still live with little knowledge of the world beyond their homelands and frequently feud with one another. Some are said to kill and eat male witches they call khakhua.

The island of New Guinea, the second largest in the world after Greenland, is a mountainous, sparsely populated tropical landmass divided between two countries: the independent nation of Papua New Guinea in the east, and the Indonesian provinces of Papua and West Irian Jaya in the west. The Korowai live in southeastern Papua.

My journey begins at Bali, where I catch a flight across the Banda Sea to the Papuan town of Timika; an American mining company's subsidiary, PT Freeport Indonesia, operates the world's largest copper and gold mine nearby. The Free Papua Movement, which consists of a few hundred rebels equipped with bows and arrows, has been fighting for independence from Indonesia since 1964. Because Indonesia has banned foreign journalists from visiting the province, I entered as a tourist.

After a stopover in Timika, our jet climbs above a swampy marsh past the airport and heads toward a high mountain. Beyond the coast, the sheer slopes rise as high as 16,500 feet above sea level and stretch for 400 miles. Waiting for me at Jayapura, a city of 200,000 on the northern coast near the border with Papua New Guinea, is Kembaren, 46, a Sumatran who came to Papua seeking adventure 16 years ago. He first visited the Korowai in 1993, and has come to know much about their culture, including some of their language. He is clad in khaki shorts and trekking boots, and his unflinching gaze and rock-hard jaw give him the look of a drill sergeant.

The best estimate is that there are some 4,000 Korowai. Traditionally, they have lived in treehouses, in groups of a dozen or so people in scattered clearings in the jungle; their attachment to their treehouses and surrounding land lies at the core of their identity, Smithsonian Institution anthropologist Paul Taylor noted in his 1994 documentary film about them, Lords of the Garden. Over the past few decades, however, some Korowai have moved to settlements established by Dutch missionaries, and in more recent years, some tourists have ventured into Korowai lands. But the deeper into the rain forest one goes, the less exposure the Korowai have had to cultures alien to their own.

After we fly from Jayapura southwest to Wamena, a jumping-off point in the Papuan highlands, a wiry young Korowai approaches us. In Bahasa Indonesia, he says that his name is Boas and that two years ago, eager to see life beyond his treehouse, he hitched a ride on a charter flight from Yaniruma, a settlement at the edge of Korowai territory. He has tried to return home, he says, but no one will take him. Boas says a returning guide has told him that his father was so upset by his son's absence that he has twice burned down his own treehouse. We tell him he can come with us.

The next morning eight of us board a chartered Twin Otter, a workhorse whose short takeoff and landing ability will get us to Yaniruma. Once we're airborne, Kembaren shows me a map: spidery lines marking lowland rivers and thousands of square miles of green jungle. Dutch missionaries who came to convert the Korowai in the late 1970s called it "the hell in the south."

After 90 minutes we come in low, following the snaking Ndeiram Kabur River. In the jungle below, Boas spots his father’s treehouse, which seems impossibly high off the ground, like the nest of a giant bird. Boas, who wears a daisy-yellow bonnet, a souvenir of “civilization,” hugs me in gratitude, and tears trickle down his cheeks.

At Yaniruma, a line of stilt huts that Dutch missionaries established in 1979, we thump down on a dirt strip carved out of the jungle. Now, to my surprise, Boas says he will postpone his homecoming to continue with us, lured by the promise of adventure with a laleo, and he cheerfully lifts a sack of foodstuffs onto his shoulders. As the pilot hurls the Twin Otter back into the sky, a dozen Korowai men hoist our packs and supplies and trudge toward the jungle in single file bound for the river. Most carry bows and arrows.

The Rev. Johannes Veldhuizen, a Dutch missionary with the Mission of the Reformed Churches, first made contact with the Korowai in 1978 and dropped plans to convert them to Christianity. "A very powerful mountain god warned the Korowai that their world would be destroyed by an earthquake if outsiders came into their land to change their customs," he told me by phone from the Netherlands a few years ago. "So we went as guests, rather than as conquerors, and never put any pressure on the Korowai to change their ways." The Rev. Gerrit van Enk, another Dutch missionary and co-author of The Korowai of Irian Jaya, coined the term "pacification line" for the imaginary border separating Korowai clans accustomed to outsiders from those farther north. In a separate phone interview from the Netherlands, he told me that he had never gone beyond the pacification line because of possible danger from Korowai clans there hostile to the presence of laleo in their territory.

As we pass through Yaniruma, I’m surprised that no Indonesian police officer demands to see the government permit issued to me allowing me to proceed. "The nearest police post is at Senggo, several days back along the river," Kembaren explains. "Occasionally a medical worker or official comes here for a few days, but they're too frightened to go deep into Korowai territory."

Entering the Korowai rain forest is like stepping into a giant watery cave. With the bright sun overhead I breathe easily, but as the porters push through the undergrowth, the tree canopy's dense weave plunges the world into a verdant gloom. The heat is stifling and the air drips with humidity. This is the haunt of giant spiders, killer snakes and lethal microbes. High in the canopy, parrots screech as I follow the porters along a barely visible track winding around rain-soaked trees and primeval palms. My shirt clings to my back, and I take frequent swigs at my water bottle. The annual rainfall here is around 200 inches, making it one of the wettest places on earth. A sudden downpour sends raindrops spearing through gaps in the canopy, but we keep walking.

The local Korowai have laid logs on the mud, and the barefoot porters cross these with ease. But, desperately trying to balance as I edge along each log, time and again I slip, stumble and fall into the sometimes waist-deep mud, bruising and scratching my legs and arms. Slippery logs as long as ten yards bridge the many dips in the land. Inching across like a tightrope walker, I wonder how the porters would get me out of the jungle were I to fall and break a leg. "What the hell am I doing here?" I keep muttering, though I know the answer: I want to encounter a people who are said to still practice cannibalism.

Hour melts into hour as we push on, stopping briefly now and then to rest. With night near, my heart surges with relief when shafts of silvery light slip through the trees ahead: a clearing. "It's Manggel," Kembaren says—another village set up by Dutch missionaries. "We'll stay the night here."

Korowai children with beads about their necks come running to point and giggle as I stagger into the village—several straw huts perched on stilts and overlooking the river. I notice there are no old people here. "The Korowai have hardly any medicine to combat the jungle diseases or cure battle wounds, and so the death rate is high," Kembaren explains. "People rarely live to middle age." As van Enk writes, Korowai routinely fall to interclan conflicts; diseases, including malaria, tuberculosis, elephantiasis and anemia, and what he calls "the khakhua complex." The Korowai have no knowledge of the deadly germs that infest their jungles, and so believe that mysterious deaths must be caused by khakhua, or witches who take on the form of men.

After we eat a dinner of river fish and rice, Boas joins me in a hut and sits cross-legged on the thatched floor, his dark eyes reflecting the gleam from my flashlight, our only source of light. Using Kembaren as translator, he explains why the Korowai kill and eat their fellow tribesmen. It's because of the khakhua, which comes disguised as a relative or friend of a person he wants to kill. "The khakhua eats the victim's insides while he sleeps," Boas explains, "replacing them with fireplace ash so the victim does not know he's being eaten. The khakhua finally kills the person by shooting a magical arrow into his heart." When a clan member dies, his or her male relatives and friends seize and kill the khakhua. "Usually, the [dying] victim whispers to his relatives the name of the man he knows is the khakhua," Boas says. "He may be from the same or another treehouse."

I ask Boas whether the Korowai eat people for any other reason or eat the bodies of enemies they've killed in battle. "Of course not," he replies, giving me a funny look. "We don't eat humans, we only eat khakhua."

The killing and eating of khakhua has reportedly declined among tribespeople in and near the settlements. Rupert Stasch, an anthropologist at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, who has lived among the Korowai for 16 months and studied their culture, writes in the journal Oceania that Korowai say they have "given up" killing witches partly because they were growing ambivalent about the practice and partly in reaction to several incidents with police. In one in the early '90s, Stasch writes, a Yaniruma man killed his sister's husband for being a khakhua. The police arrested the killer, an accomplice and a village head. "The police rolled them around in barrels, made them stand overnight in a leech-infested pond, and forced them to eat tobacco, chili peppers, animal feces, and unripe papaya," he writes. Word of such treatment, combined with Korowais' own ambivalence, prompted some to limit witch-killing even in places where police do not venture.

Still, the eating of khakhua persists, according to my guide, Kembaren. "Many khakhua are murdered and eaten each year," he says, citing information he says he has gained from talking to Korowai who still live in treehouses.

On our third day of trekking, after hiking from soon after sunrise to dusk, we reach Yafufla, another line of stilt huts set up by Dutch missionaries. That night, Kembaren takes me to an open hut overlooking the river, and we sit by a small campfire. Two men approach through the gloom, one in shorts, the other naked save for a necklace of prized pigs' teeth and a leaf wrapped about the tip of his penis. "That's Kilikili," Kembaren whispers, "the most notorious khakhua killer." Kilikili carries a bow and barbed arrows. His eyes are empty of expression, his lips are drawn in a grimace and he walks as soundlessly as a shadow.

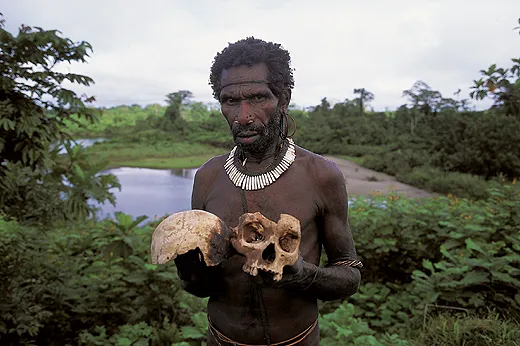

The other man, who turns out to be Kilikili's brother Bailom, pulls a human skull from a bag. A jagged hole mars the forehead. "It's Bunop, the most recent khakhua he killed," Kembaren says of the skull. "Bailom used a stone ax to split the skull open to get at the brains." The guide's eyes dim. "He was one of my best porters, a cheerful young man," he says.

Bailom passes the skull to me. I don't want to touch it, but neither do I want to offend him. My blood chills at the feel of naked bone. I have read stories and watched documentaries about the Korowai, but as far as I know none of the reporters and filmmakers had ever gone as far upriver as we're about to go, and none I know of had ever seen a khakhua's skull.

The fire's reflection flickers on the brothers' faces as Bailom tells me how he killed the khakhua, who lived in Yafufla, two years ago. "Just before my cousin died he told me that Bunop was a khakhua and was eating him from the inside," he says, with Kembaren translating. "So we caught him, tied him up and took him to a stream, where we shot arrows into him."

Bailom says that Bunop screamed for mercy all the way, protesting that he was not a khakhua. But Bailom was unswayed. "My cousin was close to death when he told me and would not lie," Bailom says.

At the stream, Bailom says, he used a stone ax to chop off the khakhua's head. As he held it in the air and turned it away from the body, the others chanted and dismembered Bunop's body. Bailom, making chopping movements with his hand, explains: "We cut out his intestines and broke open the rib cage, chopped off the right arm attached to the right rib cage, the left arm and left rib cage, and then both legs."

The body parts, he says, were individually wrapped in banana leaves and distributed among the clan members. "But I kept the head because it belongs to the family that killed the khakhua," he says. "We cook the flesh like we cook pig, placing palm leaves over the wrapped meat together with burning hot river rocks to make steam."

Some readers may believe that these two are having me on—that they are just telling a visitor what he wants to hear—and that the skull came from someone who died from some other cause. But I believe they were telling the truth. I spent eight days with Bailom, and everything else he told me proved factual. I also checked with four other Yafufla men who said they had joined in the killing, dismembering and eating of Bunop, and the details of their accounts mirrored reports of khakhua cannibalism by Dutch missionaries who lived among the Korowai for several years. Kembaren clearly accepted Bailom’s story as fact.

Around our campfire, Bailom tells me he feels no remorse. "Revenge is part of our culture, so when the khakhua eats a person, the people eat the khakhua," he says. (Taylor, the Smithsonian Institution anthropologist, has described khakhua-eating as "part of a system of justice.") "It's normal," Bailom says. "I don't feel sad I killed Bunop, even though he was a friend."

In cannibal folklore, told in numerous books and articles, human flesh is said to be known as "long pig" because of its similar taste. When I mention this, Bailom shakes his head. "Human flesh tastes like young cassowary," he says, referring to a local ostrich-like bird. At a khakhua meal, he says, both men and women—children do not attend—eat everything but bones, teeth, hair, fingernails and toenails and the penis. "I like the taste of all the body parts," Bailom says, "but the brains are my favorite." Kilikili nods in agreement, his first response since he arrived.

When the khakhua is a member of the same clan, he is bound with rattan and taken up to a day's march away to a stream near the treehouse of a friendly clan. "When they find a khakhua too closely related for them to eat, they bring him to us so we can kill and eat him," Bailom says.

He says he has personally killed four khakhua. And Kilikili? Bailom laughs. "He says he'll tell you now the names of 8 khakhua he's killed," he replies, "and if you come to his treehouse upriver, he'll tell you the names of the other 22."

I ask what they do with the bones.

"We place them by the tracks leading into the treehouse clearing, to warn our enemies," Bailom says. "But the killer gets to keep the skull. After we eat the khakhua, we beat loudly on our treehouse walls all night with sticks" to warn other khakhua to stay away.

As we walk back to our hut, Kembaren confides that "years ago, when I was making friends with the Korowai, a man here at Yafufla told me I'd have to eat human flesh if they were to trust me. He gave me a chunk," he says. "It was a bit tough but tasted good."

That night it takes me a long time to get to sleep.

The next morning Kembaren brings to the hut a 6-year-old boy named Wawa, who is naked except for a necklace of beads. Unlike the other village children, boisterous and smiling, Wawa is withdrawn and his eyes seem deeply sad. Kembaren wraps an arm around him. "When Wawa's mother died last November—I think she had TB, she was very sick, coughing and aching—people at his treehouse suspected him of being a khakhua," he says. "His father died a few months earlier, and they believed [Wawa] used sorcery to kill them both. His family was not powerful enough to protect him at the treehouse, and so this January his uncle escaped with Wawa, bringing him here, where the family is stronger." Does Wawa know the threat he is facing? "He's heard about it from his relatives, but I don't think he fully understands that people at his treehouse want to kill and eat him, though they'll probably wait until he's older, about 14 or 15, before they try. But while he stays at Yafufla, he should be safe."

Soon the porters heft our equipment and head toward the jungle. "We're taking the easy way, by pirogue," Kembaren tells me. Bailom and Kilikili, each gripping a bow and arrows, have joined the porters. "They know the clans upriver better than our Yaniruma men," Kembaren explains.

Bailom shows me his arrows, each a yard-long shaft bound with vine to an arrowhead designed for a specific prey. Pig arrowheads, he says, are broad-bladed; those for birds, long and narrow. Fish arrowheads are pronged, while the arrowheads for humans are each a hand's span of cassowary bone with six or more barbs carved on each side—to ensure terrible damage when cut away from the victim's flesh. Dark bloodstains coat these arrowheads.

I ask Kembaren if he is comfortable with the idea of two cannibals accompanying us. "Most of the porters have probably eaten human flesh," he answers with a smile.

Kembaren leads me down to the Ndeiram Kabur River, where we board a long, slender pirogue. I settle in the middle, the sides pressing against my body. Two Korowai paddlers stand at the stern, two more at the bow, and we push off, steering close by the riverbank, where the water flow is slowest. Each time the boatmen maneuver the pirogue around a sandbar, the strong current in the middle of the river threatens to tip us over. Paddling upriver is tough, even for the muscular boatmen, and they frequently break into Korowai song timed to the slap of the paddles against the water, a yodeling chant that echoes along the riverbank.

High green curtains of trees woven with tangled streamers of vine shield the jungle. A siren scream of cicadas pierces the air. The day passes in a blur, and night descends quickly.

And that's when we are accosted by the screaming men on the riverbank. Kembaren refuses to come to their side of the river. "It's too dangerous," he whispers. Now the two Korowai armed with bows and arrows are paddling a pirogue toward us. I ask Kembaren if he has a gun. He shakes his head no.

As their pirogue bumps against ours, one of the men growls that laleo are forbidden to enter their sacred river, and that my presence angers the spirits. Korowai are animists, believing that powerful beings live in specific trees and parts of rivers. The tribesman demands that we give the clan a pig to absolve the sacrilege. A pig costs 350,000 rupiahs, or about $40. It's a Stone Age shakedown. I count out the money and pass it to the man, who glances at the Indonesian currency and grants us permission to pass.

What use is money to these people? I ask Kembaren as our boatmen paddle to safety upriver. "It's useless here," he answers, "but whenever they get any money, and that's rare, the clans use it to help pay bride prices for Korowai girls living closer to Yaniruma. They understand the dangers of incest, and so girls must marry into unrelated clans."

About an hour farther up the river, we pull up onto the bank, and I scramble up a muddy slope, dragging myself over the slippery rise by grasping exposed tree roots. Bailom and the porters are waiting for us and wearing worried faces. Bailom says that the tribesmen knew we were coming because they had intercepted the porters as they passed near their treehouses.

Would they really have killed us if we hadn't paid up? I ask Bailom, through Kembaren. Bailom nods: "They'd have let you pass tonight because they knew you'd have to return downriver. Then, they'd ambush you, some firing arrows from the riverbank and others attacking at close range in their pirogues."

The porters string all but one of the tarpaulins over our supplies. Our shelter for the night is four poles set in a square about four yards apart and topped by a tarp with open sides. Soon after midnight a downpour drenches us. The wind sends my teeth chattering, and I sit disconsolately hugging my knees. Seeing me shivering, Boas pulls my body against his for warmth. As I drift off, deeply fatigued, I have the strangest thought: this is the first time I've ever slept with a cannibal.

We leave at first light, still soaked. At midday our pirogue reaches our destination, a riverbank close by the treehouse, or khaim, of a Korowai clan that Kembaren says has never before seen a white person. Our porters arrived before us and have already built a rudimentary hut. "I sent a Korowai friend here a few days ago to ask the clan to let us visit them," Kembaren says. "Otherwise they'd have attacked us."

I ask why they've given permission for a laleo to enter their sacred land. "I think they're as curious to see you, the ghost-demon, as you are to see them," Kembaren answered.

At midafternoon, Kembaren and I hike 30 minutes through dense jungle and ford a deep stream. He points ahead to a treehouse that looks deserted. It perches on a decapitated banyan tree, its floor a dense latticework of boughs and strips of wood. It's about ten yards off the ground. "It belongs to the Letin clan," he says. Korowai are formed into what anthropologists call patriclans, which inhabit ancestral lands and trace ownership and genealogy through the male line.

A young cassowary prances past, perhaps a family pet. A large pig, flushed from its hiding place in the grass, dashes into the jungle. "Where are the Korowai?" I ask. Kembaren points to the treehouse. "They’re waiting for us."

I can hear voices as I climb an almost vertical pole notched with footholds. The interior of the treehouse is wreathed in a haze of smoke rent by beams of sunlight. Young men are bunched on the floor near the entrance. Smoke from hearth fires has coated the bark walls and sago-leaf ceiling, giving the hut a sooty odor. A pair of stone axes, several bows and arrows and net bags are tucked into the leafy rafters. The floor creaks as I settle cross-legged onto it.

Four women and two children sit at the rear of the treehouse, the women fashioning bags from vines and studiously ignoring me. "Men and women stay on different sides of the treehouse and have their own hearths," says Kembaren. Each hearth is made from strips of clay-coated rattan suspended over a hole in the floor so that it can be quickly hacked loose, to fall to the ground, if a fire starts to burn out of control.

A middle-aged man with a hard-muscled body and a bulldog face straddles the gender dividing line. Speaking through Boas, Kembaren makes small talk about crops, the weather and past feasts. The man grips his bow and arrows and avoids my gaze. But now and then I catch him stealing glances in my direction. "That's Lepeadon, the clan's khen-mengga-abül, or 'fierce man,'" Kembaren says. The fierce man leads the clan in fights. Lepeadon looks up to the task.

"A clan of six men, four women, three boys and two girls live here," Kembaren says. "The others have come from nearby treehouses to see their first laleo."

After an hour of talk, the fierce man moves closer to me and, still unsmiling, speaks. "I knew you were coming and expected to see a ghost, but now I see you're just like us, a human," he says, as Boas translates to Kembaren and Kembaren translates to me.

A youngster tries to yank my pants off, and he almost succeeds amid a gale of laughter. I join in the laughing but keep a tight grip on my modesty. The Rev. Johannes Veldhuizen had told me that Korowai he’d met had thought him a ghost-demon until they spied him bathing in a stream and saw that he came equipped with all the requisite parts of a yanop, or human being. Korowai seemed to have a hard time understanding clothing. They call it laleo-khal, "ghost-demon skin," and Veldhuizen told me they believed his shirt and pants to be a magical epidermis that he could don or remove at will.

"We shouldn't push the first meeting too long," Kembaren now tells me as he rises to leave. Lepeadon follows us to the ground and grabs both my hands. He begins bouncing up and down and chanting, "nemayokh" ("friend"). I keep up with him in what seems a ritual farewell, and he swiftly increases the pace until it is frenzied, before he suddenly stops, leaving me breathless.

"I've never seen that before," Kembaren says. "We've just experienced something very special." It was certainly special to me. In four decades of journeying among remote tribes, this is the first time I've encountered a clan that has evidently never seen anyone as light-skinned as me. Enthralled, I find my eyes tearing up as we return to our hut.

The next morning four Korowai women arrive at our hut carrying a squawking green frog, several locusts and a spider they say they just caught in the jungle. "They've brought your breakfast," Boas says, smiling as his gibe is translated. Two years in a Papuan town has taught him that we laleo wrinkle our noses at Korowai delicacies. The young women have circular scars the size of large coins running the length of their arms, around the stomach and across their breasts. "The marks make them look more beautiful," Boas says.

He explains how they are made, saying circular pieces of bark embers are placed on the skin. It seems an odd way to add beauty to the female form, but no more bizarre than tattoos, stiletto-heel shoes, Botox injections or the not-so-ancient Chinese custom of slowly crushing infant girls' foot bones to make their feet as small as possible.

Kembaren and I spend the morning talking to Lepeadon and the young men about Korowai religion. Seeing spirits in nature, they find belief in a single god puzzling. But they too recognize a powerful spirit, named Ginol, who created the present world after having destroyed the previous four. For as long as the tribal memory reaches back, elders sitting around fires have told the younger ones that white-skinned ghost-demons will one day invade Korowai land. Once the laleo arrive, Ginol will obliterate this fifth world. The land will split apart, there will be fire and thunder, and mountains will drop from the sky. This world will shatter, and a new one will take its place. The prophecy is, in a way, bound to be fulfilled as more young Korowai move between their treehouses and downriver settlements, which saddens me as I return to our hut for the night.

The Korowai, believing that evil spirits are most active at night, usually don’t venture out of their treehouses after the sun sets. They divide the day into seven distinct periods—dawn, sunrise, midmorning, noon, midafternoon, dusk and night. They use their bodies to count numbers. Lepeadon shows me how, ticking off the fingers of his left hand, then touching his wrist, forearm, elbow, upper arm, shoulder, neck, ear and the crown of the head, and moving down the other arm. The tally comes to 25. For anything greater than that, the Korowai start over and add the word laifu, meaning “turn around.”

In the afternoon I go with the clan to the sago palm fields to harvest their staple food. Two men hack down a sago palm, each with a hand ax made from a fist-size chunk of hard, dark stone sharpened at one end and lashed with vine to a slim wooden handle. The men then pummel the sago pith to a pulp, which the women sluice with water to produce a dough they mold into bite-size pieces and grill.

A snake that falls from the toppling palm is swiftly killed. Lepeadon then loops a length of rattan about a stick and rapidly pulls it to and fro next to some shavings on the ground, producing tiny sparks that start a fire. Blowing hard to fuel the growing flame, he places the snake under a pile of burning wood. When the meat is charred, I'm offered a piece of it. It tastes like chicken.

On our return to the treehouse, we pass banyan trees, with their dramatic, aboveground root flares. The men slam their heels against these appendages, producing a thumping sound that travels across the jungle. "That lets the people at the treehouse know they're coming home, and how far away they are," Kembaren tells me.

My three days with the clan pass swiftly. When I feel they trust me, I ask when they last killed a khakhua. Lepeadon says it was near the time of the last sago palm feast, when several hundred Korowai gathered to dance, eat vast quantities of sago palm maggots, trade goods, chant fertility songs and let the marriage-age youngsters eye one another. According to our porters, that dates the killing to just over a year ago.

Lepeadon tells Boas he wants me to stay longer, but I have to return to Yaniruma to meet the Twin Otter. As we board the pirogue, the fierce man squats by the riverside but refuses to look at me. When the boatmen push away, he leaps up, scowls, thrusts a cassowary-bone arrow across his bow, yanks on the rattan string and aims at me. After a few moments, he smiles and lowers the bow—a fierce man's way of saying goodbye.

In midafternoon, the boatmen steer the pirogue to the edge of a swamp forest and tie it to a tree trunk. Boas leaps out and leads the way, setting a brisk pace. After an hour’s trek, I reach a clearing about the size of two football fields and planted with banana trees. Dominating it is a treehouse that soars about 75 feet into the sky. Its springy floor rests on several natural columns, tall trees cut off at the point where branches once flared out.

Boas is waiting for us. Next to him stands his father, Khanduop, a middle-aged man clad in rattan strips about his waist and a leaf covering part of his penis. He grabs my hand and thanks me for bringing his son home. He has killed a large pig for the occasion, and Bailom, with what seems to me to be superhuman strength, carries it on his back up a notched pole into the treehouse. Inside, every nook and cranny is crammed with bones from previous feasts—spiky fish skeletons, blockbuster pig jaws, the skulls of flying foxes and rats. The bones dangle even from hooks strung along the ceiling, near bundles of many-colored parrot and cassowary feathers. The Korowai believe that the décor signals hospitality and prosperity.

I meet Yakor, a tall, kindly eyed tribesman from a treehouse upriver, who squats by the fire with Khanduop, Bailom and Kilikili. Boas’ mother is dead, and Khanduop, a fierce man, has married Yakor's sister. When the talk turns to khakhua meals they have enjoyed, Khanduop's eyes light up. He's dined on many khakhua, he says, and the taste is the most delicious of any creature he's ever eaten.

The next morning the porters depart for the river, carrying our remaining supplies. But before I leave, Khanduop wants to talk; his son and Kembaren translate. "Boas has told me he'll live in Yaniruma with his brother, coming back just for visits," he murmurs. Khanduop's gaze clouds. "The time of the true Korowai is coming to an end, and that makes me very sad."

Boas gives his father a wan smile and walks with me to the pirogue for the two-hour journey to Yaniruma, wearing his yellow bonnet as if it were a visa for the 21st century.

Three years earlier I had visited the Korubo, an isolated indigenous tribe in the Amazon, together with Sydney Possuelo, then director of Brazil's Department for Isolated Indians [SMITHSONIAN, April 2005]. This question of what to do with such peoples—whether to yank them into the present or leave them untouched in their jungles and traditions—had troubled Possuelo for decades. "I believe we should let them live in their own special worlds," he told me, "because once they go downriver to the settlements and see what is to them the wonders and magic of our lives, they never go back to live in a traditional way."

So it is with the Korowai. They have at most a generation left in their traditional culture—one that includes practices that admittedly strike us as abhorrent. Year by year the young men and women will drift to Yaniruma and other settlements until only aging clan members are left in the treehouses. And at that point Ginol's godly prophecy will reach its apocalyptic fulfillment, and thunder and earthquakes of a kind will destroy the old Korowai world forever.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.