Tattooing Was Illegal in New York City Until 1997

The New-York Historical Society’s newest exhibit delves into the history of the city’s once-turbulent ink scene

In 1961, it officially became illegal to give someone a tattoo in New York City. But Thom deVita didn’t let this new restriction deter him from inking people. The day after it was put into law, the tattoo artist quietly opened the doors of his tattoo shop in Alphabet City, then one of the grittiest neighborhoods in the area. He limited himself to just five clients per day, working late at night when many other people were asleep. While these may seem like temporary measures for such a vibrant city that seldom sleeps, it wouldn’t be until 1997—36 years later—that it would finally lift the ban.

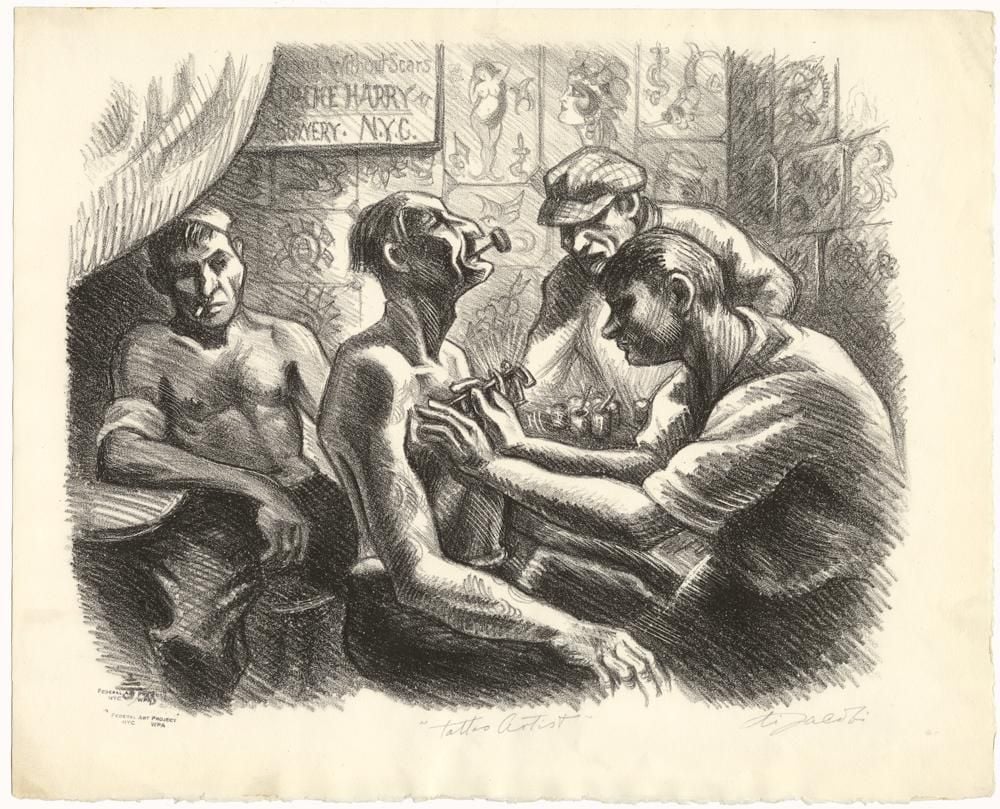

This is just one of the many interesting facets of the city’s storied ink history covered in “Tattooed New York,” an exhibition dedicated to epidermal art and its history that is on display through April 30 at the New-York Historical Society Museum and Library. The show contains more than 250 objects, artworks, photographs, videos and other documents stretching from the early 1700s to now, including Thomas Edison's electric pen, the percusor to the tattoo gun, and a Norman Rockwell oil painting of a man getting inked.

So what exactly caused the city to crack down on tattoos in the first place? After all, isn’t New York City where people go to express their individuality—and arguably, what better way is there to do so than by getting a tattoo?

“From the research I’ve done and the tattoo artists I’ve met from that era, there are various reasons [behind] why the ban took place,” Cristian Petru Panaite, assistant curator of exhibitions at the historical society, tells Smithsonian.com. “[The city claimed that there was] an outbreak of hepatitis B, while others suspected it was because the city wanted to clean up before the [1964] World’s Fair. There’s also supposedly a love story involving a city official and one of the tattooer’s wives, and that kind of turns into a personal vendetta.”

Panaite organized the exhibition in chronological order, beginning with Native Americans, specifically the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) tribe, who resided on the same land where the city now sits. Tribal members believed that tattoos had healing powers and provided protection from evil, and they would apply them by cutting into the skin and sprinkling soot or crushed minerals into the wound. They also used tattoos as a form of identification, a common thread that comes up several times throughout the exhibit.

Sailors, for example, another group of tattoo aficionados, started getting their initials inked onto their skin at some point in the 1700s. These distinctive tattoos were then recorded in their personal Seamen’s Protection Certificates, which were used as identification and to help stave off impressment. Fast forward to 1936, the year in which the U.S. government introduced Social Security Numbers, and some citizens came up with a clever way to remember their information.

“People were trying to figure out what to do with their numbers, and the government told people to keep them safe,” Panaite says. “So quite a few people thought the safest place would be on their skin.”

One piece of history that is often overshadowed, and on which the exhibition focuses, is the popularity of tattoos among women. During the Victorian era, fashionable women would discreetly invite tattoo artists to their homes to get inked, often commissioning designs in areas of their bodies that could easily be hidden, such as on a wrist, which could be covered by a bracelet. The famous New York writer Dorothy Parker, for example, had a small blue star tattooed on the inside of her bicep. A report by the now defunct newspaper New York World even claimed that by 1900 more women than men in New York City sported tattoos. And the popularity only grew from there.

Soon, more visibly tattooed women began working on the sideshow stage in places like Brooklyn's Coney Island and at dime museums along the Bowery, flaunting their bodily canvases. It was not only a way for them to make a living, but also, Panaite argues, a source of empowerment.

“Over the years, the story of the tattoo industry has been more male-centric,” Panaite says. “But I noticed in my research that women kept popping up and were making these strong statements.”

Panaite refers to Mildred (Millie) Hull, born in 1897 and said to be the first woman to open a tattoo shop on the Bowery. For practice, Hull would tattoo herself, eventually acquiring more than 300 such inks.

Today, tattoos are no longer seen as the taboo that they once were, and have become firmly planted within American society. Everyone from teachers to lawyers to museum curators sport them (yes—Panaite admits to getting two while curating the show). New York City is home to more than 270 tattoo studios today, and as part of the exhibition, the historical society has invited several tattoo artists to conduct live demos as part of the show.

"You get to see artwork being made," Panaite says. "It's pretty amazing."

And after seeing the exhibition, you too may be inspired to get inked.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4d/08/4d086f2b-969b-41e3-8687-ae4e443dd9b0/2_edisonpen.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/cd/d0cd8508-f3f1-4cb1-a4d2-ec1031076074/9_ace_harlyn_-_mildredhull-painting.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/69/4669842d-a7f8-45e3-ac10-213caa23691d/10_coneyislandfreddieshop.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/47/ef/47efc560-6291-4966-bae8-c3169a7c7154/15_familyatthenyctattooconvetion.jpg)