The Pathway Home Makes Inroads in Treating PTSD

An innovative California facility offers hope to combatants with post-traumatic stress disorder and brain injuries

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Pathway-Home-residents-631.jpg)

They went off to war brimming with confidence and eager for the fight in Iraq and Afghanistan. They returned, many of them, showing no visible wounds but utterly transformed by combat—with symptoms of involuntary trembling, irritability, restlessness, depression, nightmares, flashbacks, insomnia, emotional numbness, sensitivity to noise, and, all too often, a tendency to seek relief in alcohol, drugs or suicide.

“Families and friends are shocked when one of these guys comes back,” says Fred Gusman, a social worker and mental health specialist now serving as director of the Pathway Home, a nonprofit residential treatment center in Yountville, California, where active and retired service members suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) are learning to make the hard transition from war to civilian life.

“The guy who looked like G.I. Joe when he left home comes back a different person,” says Gusman, a Vietnam-era veteran who pioneered treatment for warriors suffering from stress-related illness in the 1970s. “We called it post-Vietnam syndrome back then,” Gusman adds, noting a link between combat and mental trauma that dates to the Civil War. That war produced an anxiety disorder known as “soldier’s heart”; World War I gave rise to shell shock; World War II and Korea produced battle fatigue.

Each clash of arms spawned its own array of psychic injuries, with striking similarities to those haunting thousands of combatants from the current wars. “You get the 10,000-mile stare,” says Gusman. “You shut down emotionally except when you’re raging with anger. You are hyper-vigilant because you don’t know where the enemy is. You look for signs of trouble in the line at Wal-Mart, or when someone crowds you on the freeway, or when there’s a sudden noise. They are very, very watchful. This kept them alive in Iraq and Afghanistan, but it becomes a problem when they come home. It’s not like a light switch you can turn off or on. I tell the guys they have to play detective, to figure out why they’re angry or anxious and unravel it. We give them the tools to realize when they’re spinning and need to stop. They learn to modulate their emotions.”

Since opening his facility on the grounds of Yountville’s Veterans Home of California in 2008, Gusman and his staff of 18 have treated almost 200 wounded warriors, many of whom had found only frustration when they sought treatment at military hospitals or V.A. centers.

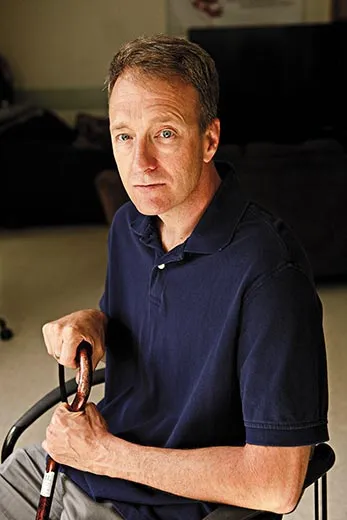

“There’s no compassion. I felt constantly ridiculed,” says Lucas Dunjaski, a former Marine corporal diagnosed with PTSD in 2004 while serving in Iraq. Returning home, he ran into marital difficulties, drank heavily and sought treatment at the V.A. Hospital in Menlo Park, California, which specializes in PTSD care. He gave up after two one-week hospital stays a year apart. “It wasn’t a healing environment,” he recalls. “I tried to commit suicide. I just couldn’t pull it together.” (Since Dunjaski’s V.A. experience, the Department of Veterans Affairs announced in July that it is easing the process for those seeking disability for PTSD.) For his part, Dunjaski enrolled in the Pathway program last spring, which handles as many as 34 patients at a time. “I came here thinking it was my last option. I would be dead if I didn’t have this program,” says Dunjaski, now 25. Finishing treatment in July, he felt that things were finally looking up: he had just moved into a house with his new wife and had hopes for the future. “I know I’m going to be OK.”

What differentiates Pathway from standard facilities? A seasoned staff with military experience, few patients, a high tolerance for emotional outbursts and eccentric behavior, the collegial atmosphere of a campus instead of a hospital setting and a willingness to try anything. Realizing that Pathway could treat a mere fraction of the 30,000 veterans returning to California each year, Gusman resolved to create a model program that the V.A. and others could adapt. One such program, the recently opened National Intrepid Center of Excellence for treating TBI and psychological ailments in Bethesda, Maryland, takes a holistic approach to treatment, inspired, in part, by Gusman’s program.

The Pathway team carefully monitors medications, guides veterans through treatment for substance and alcohol abuse, encourages regular morning walks in the hills and watches for signs of TBI, a head injury that produces short-term memory loss, difficulty with speech and balance problems. “Many of our guys have some TBI on top of PTSD,” says Gusman. “The two conditions overlap, so you’re not going to know right away if it’s TBI, PTSD or both. It takes a willingness to ride the waves with the guys to help figure out what’s agitating them. Other places don’t have that sort of time. I think that’s why traditional institutions struggle with this population. We’re open to anything.”

While most patients leave Pathway after a few months, Gusman has treated some for as long as a year. “What do you do?” he asks. “Throw them away?” Because of Gusman’s willingness to experiment, the Pathway program has an improvisational quality, which includes family counselors, yoga instructors, acupuncturists, service dogs and twice-weekly follow-up text messages to support graduates and monitor how they are faring.

Gusman and his staff preside over anger management sessions, prod patients for details of their prewar history and coach them on how to navigate the V.A. system. They gradually reintroduce the men to life in Napa Valley, where Rotary Club members and others from the community have adopted Gusman’s ragtag band of brothers: veterans go bowling, tour the countryside on bikes, learn fly-fishing—all Gusman’s way of keeping them busy and breaking their sense of isolation. “The real test is when you go outside,” he says. “That’s why we encourage them to get out into the community.”

Inside, patients talk about their wartime experience in group meetings known as trauma sessions, which are at the core of the Pathway program. In these arduous talkfests, warriors relive their days on the front lines, recalling scenes they would rather forget—the friend cut in half by an improvised explosive device, the comrade killed because he could not bring himself to shoot the enemy who used a child as a shield, the young warrior who lost one leg in an explosion and awoke as the other was being amputated, the Navy corpsman working frantically to save severely wounded Marines as bullets whizzed by his head and hope slipped away.

“No movie begins to portray the horror, the shock, the emotional aspect of being there,” says that Navy corpsman, retired Senior Chief Trevor Dallas-Orr. Like others who have been through the Pathway program, Dallas-Orr, a decorated veteran of the first Gulf War and Iraq, credits Pathway with saving his life.

“I lost my family, my job, my home, my identity,” recalls Dallas-Orr, 45, who was living out of his car when he vainly sought treatment in the V.A. system. “Fred’s team opened me up and I started to realize, ‘Hey, this is a good thing.’ If it hadn’t been for this place, I’d be dead. I would’ve just melted away.”

After almost a year of treatment at Pathway, Dallas-Orr returned home to Southern California this past spring. He still struggles with nightmares, insomnia and outbursts of anger, but he has learned to manage them, and he has re-established contact with his two estranged sons. He recently spoke to an audience of several hundred people in San Diego for Operation Welcome Home, an event organized by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger to honor returning warriors. “No way in hell I could have done that before,” says Dallas-Orr.

Sitting across the table, Gusman credits Dallas-Orr and his fellow warriors with their own revival. “Well, I always say you guys are doing it yourselves,” says Gusman. “It’s your courage that pushes you forward. Our joy is seeing you being successful in your own right. That’s how we get our goodies.”

Gusman’s program faces an uncertain future, however. Pathway’s one-time initial grant of $5 million ran out in August. The center is raising funds to keep its doors open.

Robert M. Poole is a contributing editor. Photographer Catherine Karnow is based in Mill Valley, California.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.