The Wonderful Wilderness of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula

Immortalized by Longfellow, the Midwest’s preferred vacation spot offers unspoiled forests, waterfalls and coastal villages

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Destination-America-Michigan-Presque-Isle-cove-631.jpg)

From the summit of 1,327-foot Marquette Mountain in northern Michigan, the view offers a pleasing mix of industrial brawn and natural beauty. Dense pine forests descend to the red sandstone churches and office buildings of Marquette, the largest town (pop. 20,714) in the Upper Peninsula, or UP. In Marquette’s harbor on Lake Superior, the world’s largest body of fresh water, a massive elevated ore dock disgorges thousands of tons of iron pellets into the hold of a 1,000-foot-long ship. Closer to my lofty perch, a bald eagle plunges toward unseen prey in the lake’s blue waters.

For more than a century, the UP has been the summer playground of Midwesterners. From the early 1900s on, captains of industry and commerce—including Henry Ford and Louis G. Kaufman—converged here. The industrialists erected lavish lakeside “cabins” that rivaled the Adirondack “camps” of the Eastern Seaboard elite. By the American automobile’s mid-20th-century heyday, Detroit assembly-line workers were flocking here as well.

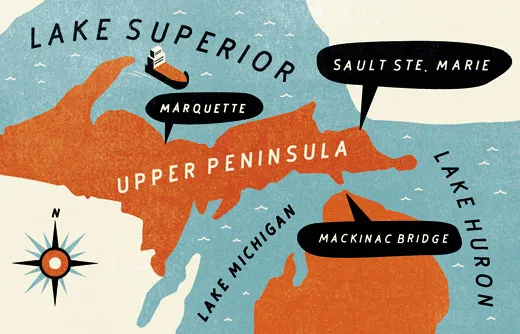

With Lake Superior to the north, Lake Michigan to the south and Lake Huron to the east, the UP covers 16,542 square miles, or about 28 percent of Michigan’s landmass. (Since 1957, the two peninsulas, Upper and Lower, have been connected by the five-mile-long Mackinac suspension bridge.) Yet only about 3 percent of the state’s population—some 317,000 residents—live amid the UP’s woodlands, waterfalls and icy trout streams. Ernest Hemingway, who fished in the UP as a boy and young man, paid homage to the region in a 1925 Nick Adams short story, “Big Two-Hearted River,” set there. “He stepped into the stream,” the novelist wrote. “His trousers clung tight to his legs. His shoes felt the gravel. The water was a rising cold shock.”

“Yoopers,” as local residents call themselves, scoff at warm-weather visitors; as much as 160 inches of snow falls annually in parts of the UP. Even in July and August, when daylight stretches past 10 p.m., Lake Superior breezes keep average temperatures below 80 degrees. By nightfall, lakeside restaurants are packed with patrons tucking into grilled whitefish and pasties (pronounced PASS-tees)—turnovers stuffed with beef, potato and onion, a regional specialty introduced more than 150 years ago by British miners from Cornwall.

I confined my nine-day journey to a scenic stretch along Lake Superior, between the heavily transited ship locks in Sault Ste. Marie (pronounced SOO Saint Ma-REE, pop. 16,542) on the east and the lonely crescent beaches of the Keweenaw Peninsula, 263 miles to the west. Looming on the horizon at nearly every turn was Lake Superior, considered an inland sea despite its fresh water—so big it holds more water than the other four Great Lakes combined. The Ojibwa tribe called it “Gichigami,” meaning “big water,” and it was memorialized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, “The Song of Hiawatha”: “By the shores of Gitche Gumee / By the shining Big-Sea-Water...”

French Explorers came to the Upper Peninsula in the 1600s for pelts, particularly beaver; they used Huron and Odawa Indians as go-betweens with trappers from other tribes. “The fur trade led Native Americans to give up their traditional way of life and plug into the global economy,” says historian Russ Magnaghi of Northern Michigan University in Marquette. The tribes also revealed locations of copper and iron deposits. By the 1840s, metal ore revenues surpassed those from fur, attracting miners from Germany, Ireland, Britain, Poland, Italy, Sweden, Norway and Finland.

At first, ore moved by boat on Lake Superior to Sault Ste. Marie, then was unloaded and carried overland by horse-drawn wagons past the St. Mary’s River rapids, a distance of some 1.5 miles. Then the ore was once again loaded onto waiting ships—a “staggeringly slow and inefficient” process, says Northern Michigan University historian Frederick Stonehouse.

But in 1853, construction began on locks to allow the ships direct passage between Superior and Huron. Sault Ste. Marie’s Soo Locks opened on schedule in 1855. “The lakes themselves became a vital highway for the Union Army in the Civil War,” says Stonehouse. In the year before the locks opened, fewer than 1,500 tons of ore were shipped; a decade later, the annual total had increased to 236,000 tons. After the war, the ore was shipped to the iron mills of Ohio and Pennsylvania. “The economic impact of Soo Locks was felt throughout the Middle West and across the nation,” says Pat Labadie, a historian at Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary on the shores of Lake Huron at Alpena, Michigan. Today, nearly 80 million tons of cargo pass through the Soo Locks each year, making it the third busiest man-made waterway after the Panama and Suez canals.

Even the mightiest feats of engineering, however, are no match for the sudden storms that lash Lake Superior. The Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point, a 75-mile drive northwest from Sault Ste. Marie, documents the final 1975 voyage of the doomed ore carrier the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, in its day the largest and fastest vessel on the lake.

On November 9, the 729-foot ship and its 29-man crew departed from the port of Superior, Wisconsin. Fully loaded with 29,000 tons of taconite iron-ore pellets, the Fitzgerald headed in calm seas for the Great Lakes Steel Company near Detroit. Some 28 hours later, the worst storm in more than three decades—waves 30 feet high and wind gusts close to 100 miles per hour—swept over Lake Superior. The Whitefish Point lighthouse was out as the vessel approached.

“We have not far to go,” the Fitzgerald’s captain, Ernest McSorley, said on the radio. “We will soon have it made. Yes, we will....It’s a hell of a night for the Whitefish beacon not to be operating.”

“It sure is,” replied Bernie Cooper, captain of the nearby Arthur M. Anderson, another ore carrier. “By the way, how are you making out with your problems?”

“We are holding our own,” McSorley answered.

Those were the last words heard from the Fitzgerald. On November 15, 1975, the ship’s twisted remains, broken into two large sections, were located 17 miles off Whitefish Point at a depth of 530 feet. No one knows just what happened. One theory holds that the force of the waves opened the vessel’s hatches and filled the hold with water. But historian Stonehouse, author of The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, believes the ship probably “struck a rocky shoal, didn’t realize it, staggered off and sunk in deep water.” Because of the danger in sending divers into water that deep, the crew’s bodies have yet to be brought to the surface.

Tahquamenon Falls State Park lies 23 miles southwest of Whitefish Point. It’s the site of two cascades that disgorge up to 50,000 gallons of water per second, putting them behind only Niagara in volume among waterfalls east of the Mississippi. The Upper Falls, surrounded by one of Michigan’s last remaining old-growth forests, features a 50-foot drop. The falls might have saved the forests by making logging there untenable. The drop over the falls would have broken logs floating downriver. Today, majestic eastern hemlocks, four centuries old, stand 80 feet high in the 1,200-acre park.

The movement of glaciers shaped Lake Superior 10,000 years ago. Today, wind and water continue to mold its shoreline. Nowhere is this more dramatic than at Pictured Rocks, a 15-mile-long expanse of cliffs northeast of the small port of Munising (pop. 2,539). I board a tour boat that makes its way into a narrow bay created by Grand Island on the west and the lakeshore to the east. As we head toward the open lake, the cliffs become less densely forested; fierce winds have sheared off treetops and branches. Some cliffs are shaped like ship hulls jutting into Superior, and crashing waves have carved caverns into others.

After a few minutes, the Pictured Rocks come into view, looking like giant, freshly painted abstract works of art. “There are a few cliff formations elsewhere along Superior, but nothing this size or with these colors,” says Gregg Bruff, who conducts education programs at Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore. Hundreds of large and small waterfalls and springs splash down the cliffs, reacting with minerals in the sandstone to create a palette of colors, including browns and reds from iron, blues and greens from copper, and black from manganese. The fragility of this natural wonder is apparent: large fragments from recently collapsed cliffs lie at the base of rock faces. In some places, the cliffs may retreat several feet in a single year. Eaten away by pounding waves, the lower portions are the first to go. “On top, there will be overhangs protruding above the water,” says Bruff. “Right now, there is one spot with an overhanging boulder the size of a four-bedroom house.” As we head back to the harbor, flocks of hungry gulls emerge from nesting holes in the cliffs, flying parallel to our boat.

Some 150 miles west, on the northwest shore of the scenic Keweenaw (KEE-wuh-naw) Peninsula, 1,328-foot Brockway Mountain offers a breathtaking prospect of Lake Superior. This is copper mining country. At Keweenaw’s tip, the tiny hamlet of Copper Harbor is Michigan’s northernmost point. During the Civil War, the port was a major loading dock for copper ore. In the century that followed, the peninsula drew vacationing families to holiday houses, many along the southeastern coast of Keweenaw Bay. Some of the beaches were created from massive amounts of gravel and sand excavated during removal of copper ore from underground mines.

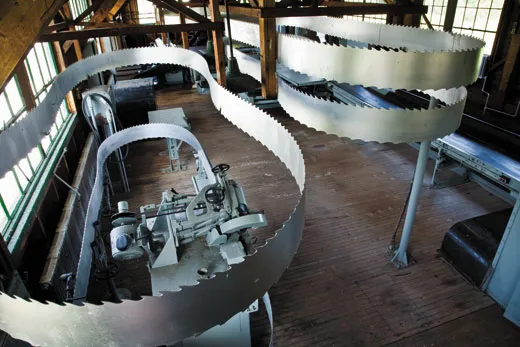

Established in 1848 midway up the Keweenaw Peninsula, the Quincy mine grew into one of the largest and most profitable underground copper mines in the country, earning the nickname Old Reliable—until its lodes declined in purity in the early 1940s. By then, Quincy’s main shaft had reached a depth of 6,400 feet—well over a mile. Today, guided tours transport visitors on a cart pulled by tractor to a depth of only 370 feet. Below, the mine has filled with water.

Tour guide Jordan Huffman describes the work routine in the mine’s heyday. “You had a three-man team, with one man holding a steel rod and two men pounding away at it with sledgehammers,” says Huffman. After each blow, the miner grasping the rod rotated it 90 degrees. At the end of a ten-hour workday, four holes would have been driven into the rock. Sixteen holes filled with dynamite formed a blast pattern that loosened a chunk of copper ore to be transported to the surface. The backbreaking work was done by the light of a single candle.

With a twinge of guilt, I return to my comfortable lodgings, the Laurium Manor Inn, a restored Victorian mansion that once belonged to mine owner Thomas H. Hoatson Jr. From my balcony I can see small-town Americana. Girls play hopscotch on the sidewalk. Young men hunch over the open hood of a Chevy Camaro, scrub the tires and wax the exterior. A songbird chorus rises from the stately oaks, hemlocks and maples shading large houses, many dating back more than a century. David and Julie Sprenger graduated from the UP’s Michigan Tech, in the town of Houghton. They abandoned careers in Silicon Valley in 1991 to transform this once-derelict mansion into an upscale bed-and-breakfast in tiny Laurium (pop. 2,126), about ten miles northeast of the Quincy mine. “We gave ourselves two years to get it up and running—and then we just couldn’t stop,” says Julie. Work on the stained glass, reupholstered furniture, carpentry, original plumbing and lighting fixtures has stretched out for 20 years. “And we still aren’t through,” she says.

Some 100 miles to the east, the town of Marquette offers a remarkable inventory of historical architecture, linked to another 19th-century mining boom—in iron ore. The single most striking structure is the now abandoned Lower Harbor Ore Dock, jutting 969 feet into Lake Superior from downtown Marquette. The Presque Isle Harbor Dock, at the town’s northern end, remains in operation. Here, loads of iron pellets are transferred from ore trains to cargo vessels.

From about 1870, iron-mining wealth funded many handsome buildings built of locally quarried red sandstone. Landmarks include the neo-Gothic First United Methodist Church (1873), with square buttressed towers and two asymmetrical spires; the Beaux-Arts-style Peter White Public Library (1904), constructed of white Bedford (Indiana) limestone; and the former First National Bank and Trust Company headquarters (1927), built by Louis G. Kaufman.

The Marquette County Courthouse, built in 1904, is where many of the scenes in the 1959 courthouse cliffhanger, Anatomy of a Murder, were filmed. The movie, starring James Stewart, Lee Remick and Ben Gazzara, was adapted from the 1958 novel of the same title by Robert Traver, the pseudonym of John Voelker, who was the defense attorney in the rape and vengeance murder case on which the book was based. “After watching an endless succession of courtroom melodramas that have more or less transgressed the bounds of human reason and the rules of advocacy,” wrote New York Times movie critic Bosley Crowther, “it is cheering and fascinating to see one that hews magnificently to a line of dramatic but reasonable behavior and proper procedure in a court.”

On my final day in the upper peninsula, I drive 58 miles from Marquette to the village of Alberta, built in the 1930s by Henry Ford, who conceived of a utopian community for his workers. In 1935, he founded such a settlement, centered around a lumber mill, at the southern end of the Keweenaw Peninsula. There the men worked in a mill that supplied lumber for components for Detroit car bodies; Alberta’s women grew fruits and vegetables on two-acre plots. The community included a dozen households, two schools and a reservoir that supplied water to the mill and offered recreation for residents.

Ford claimed he had been motivated to create Alberta—named after the daughter of one of his executives—by nostalgic memories of his own village childhood. But some are skeptical. The Depression years were a time of ideological struggle, with Fascism and Communism sweeping Europe and increasing tensions between management and labor in the United States. “Ford didn’t like unions, and saw the Alberta experiment as an alternative to keep them at bay a bit longer,” says Kari Price, who oversees the museum established at Alberta after the Ford Motor Company transferred the village to nearby Michigan Tech in 1954. Today Alberta is the location of the university’s forestry research center, and its original dozen Cape Cod-style cottages are rented to vacationers and a handful of permanent residents.

The Alberta experiment lasted only 16 years. Demand for automobile lumber ended in 1951 when Ford stopped producing “woody” station wagons, which featured slats of polished wood on the doors. And farming at Alberta turned out to be impractical: the soil was rocky, sandy and acidic; the growing season was short (90 days at best)—and the deer were voracious.

Ford’s failure, however, was not without its compensations. He envisioned establishing villages throughout the Upper Peninsula, and likely anticipated increased logging to supply the mills in future settlements. Instead, the region’s sprawling wilderness has remained intact. In the late 1950s, when the celebrated American naturalist and writer Edwin Way Teale crisscrossed the Upper Peninsula—as part of an odyssey he would recount in Journey Into Summer (1960)—he was awed by the region’s untrammeled beauty. The UP, he declared, could fairly be described as a “land of wonderful wilderness,” where “sand and pebbles and driftwood” dot the lakeshores, mayflies can be seen “rising and drifting like thistledown,” and forest glens are “filled with the hum of bees and the pink of milkweed flower clusters.” Teale wrote that he and his wife, Nellie, were reluctant even to glance at their map while driving for fear of missing a sight, whether small or spectacular: “Everywhere we felt far away from cities and twentieth-century civilization.” More than a half-century later, that assessment holds true. If you need to look at a map, it’s probably best to pull over.

Jonathan Kandell lives in New York City. Photographer Scott S. Warren travels the world on assignment.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.