These Sketches Will Take You Into the Artistic Mind of Edward Hopper

At the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, a new exhibition and a novella delve into the inexplicable sense of mystery in Hopper’s paintings

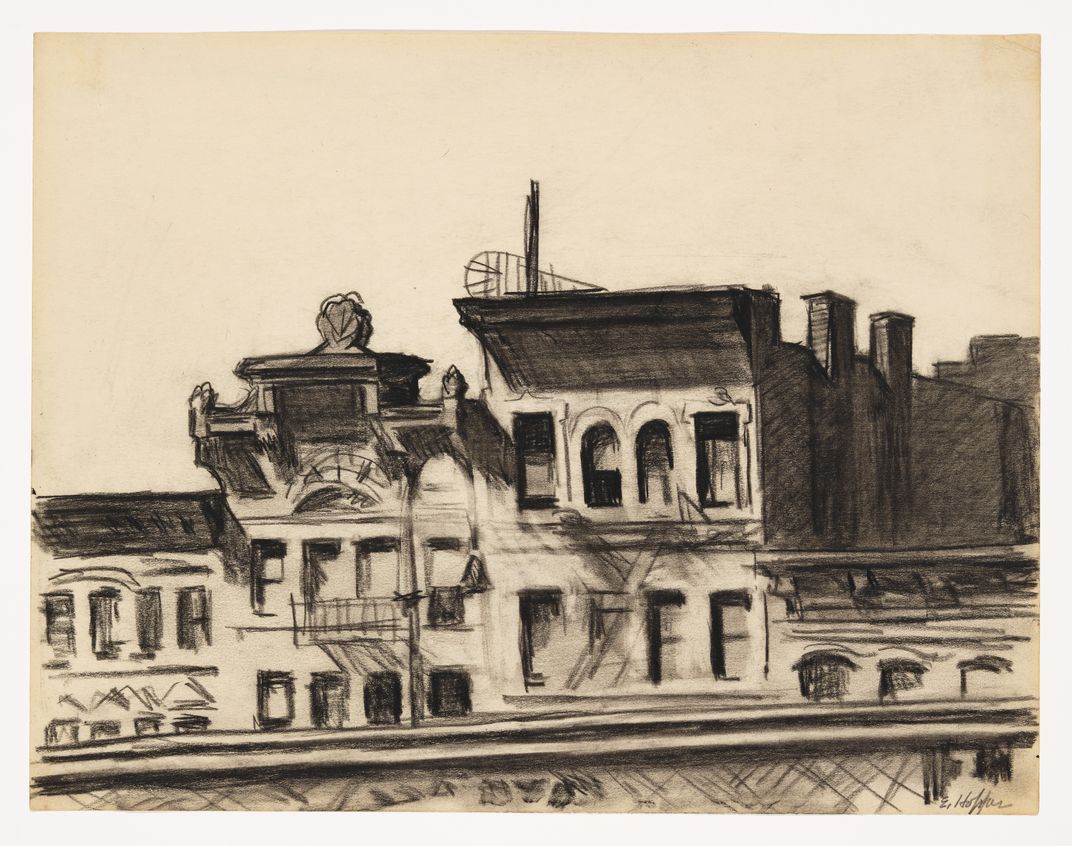

Imagine a solitary man, an artist, who, for more than a half-century, observes the fleeting moments of life as he haunts the streets and movie houses of Greenwich Village or rides the elevated train throughout Manhattan, peering down into the windows of office buildings as he rumbles past. Life unfolds all around him, but he doesn’t linger on the story; he’s more interested in the depth of feeling that these moments evoke in him. This artist was Edward Hopper (1882-1967), a shy and secretive man who, with his wife Jo, lived in a spare walk-up apartment and adjoining studio near Washington Square, rarely traveling except for summers spent in New England. Along the way, Hopper produced such icons of American art as Nighthawks (1942), the definitive American painting of a late-night diner; Rooms for Tourists (1945), the mysterious Victorian house that has influenced several generations of noir filmmakers; and Office at Night (1940), which continues to intrigue us with its sense of drama frozen in time.

Office at Night is owned by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis where—in the words of education director Sarah Schultz—it’s “one of the museum’s crown jewels.” And right now, this enigmatic painting is getting a lot of attention. For one thing, it is the centerpiece of a major exhibition, organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and now at the Walker. Entitled "Hopper Drawing: A Painter’s Process," the exhibition presents 22 of Hopper’s major oil paintings alongside the many chalk drawings that the artist made for each of them.

But the Walker—always an adventurous museum—has gone one step further with Office at Night. As Schultz explains, she and Chris Fischbach, publisher of Coffee House Press, were brainstorming when they came up with the idea of asking two prominent writers, Laird Hunt and Kate Bernheimer, to collaborate on a novella inspired by Office at Night—in essence, Schultz says, “to take up residence in the painting, coming up with one of a thousand stories that could be told about it.” The first installment of this novella has just now appeared on the museum’s website, and new ones will appear every weekday for the rest of the month. “It’s an experiment in narrative invention,” Schultz says.

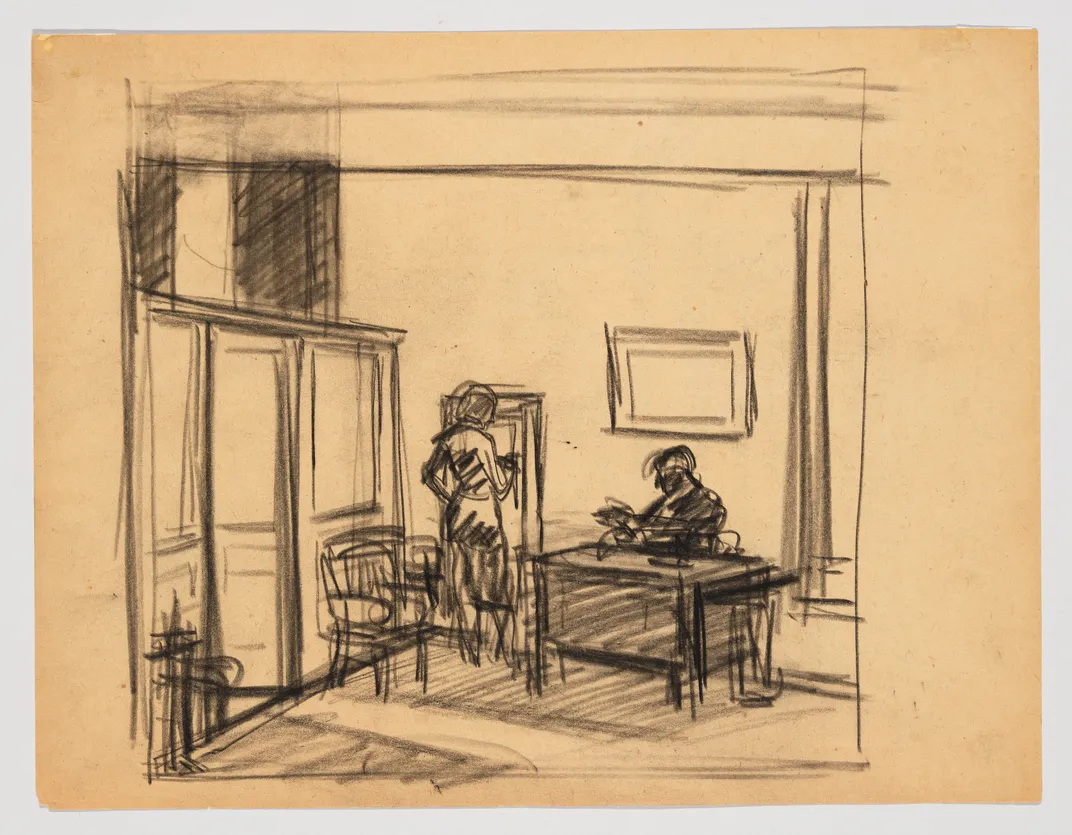

And what a perfect choice Office at Night is for this experiment. Because, while it is true that Hopper is regarded as a realistic painter who started with what he called “facts,” his paintings are so much more than simply realistic. They seem to hold secrets, layers of meaning, hinted-at narratives floating beneath the surface. They make us want to know more, to finish the story. This is certainly true of Office at Night. A man sits at a desk and a woman—apparently his secretary—stands at a filing cabinet, in a sparse office bathed in light from outside the window. She looks at him, but he looks down at a sheet of paper, and both of their bodies are oddly rigid. On the floor between them is another sheet of paper; it seems to mean something—but what? We witness this scene from a raised viewpoint, as though we are voyeurs hovering just above and outside the room. “There is this sense of tension—this narrative tension—that either something has happened, or is about to happen,” Schultz says.

Hopper didn’t like to talk about the meaning of his paintings, but he did provide one interesting clue soon after the Walker acquired Office at Night in 1948. In a letter to the museum’s director, he wrote, “The picture was probably first suggested by many rides on the ‘L’ train in New York after dark, and glimpses of office interiors that were so fleeting as to leave fresh and vivid impressions on my mind.”

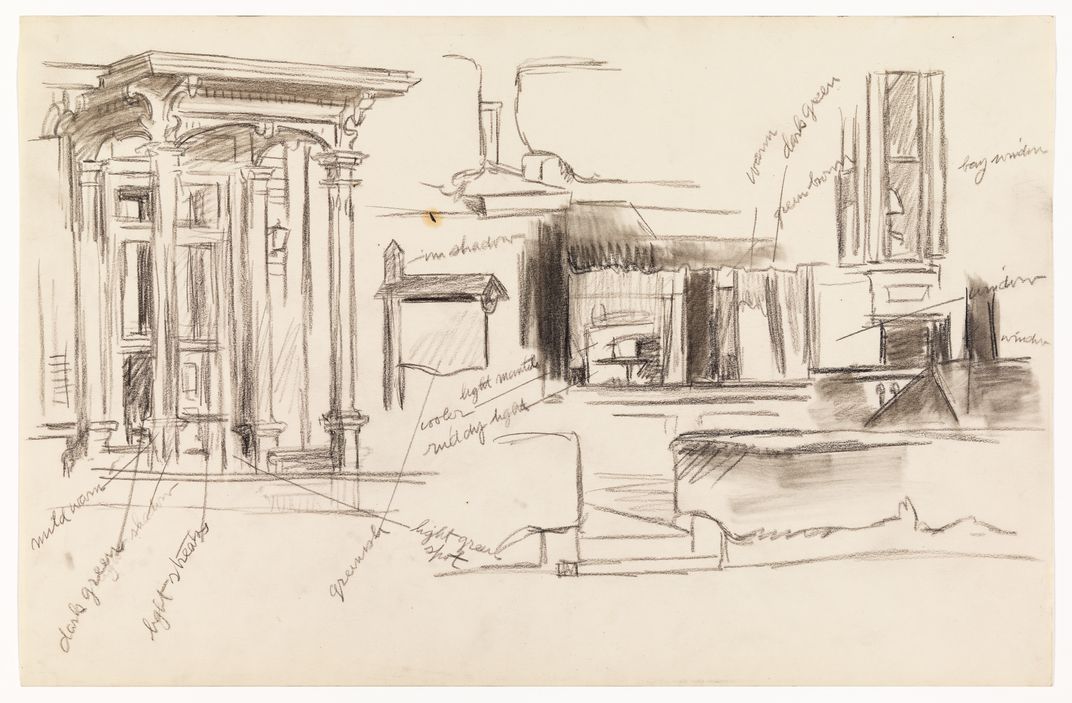

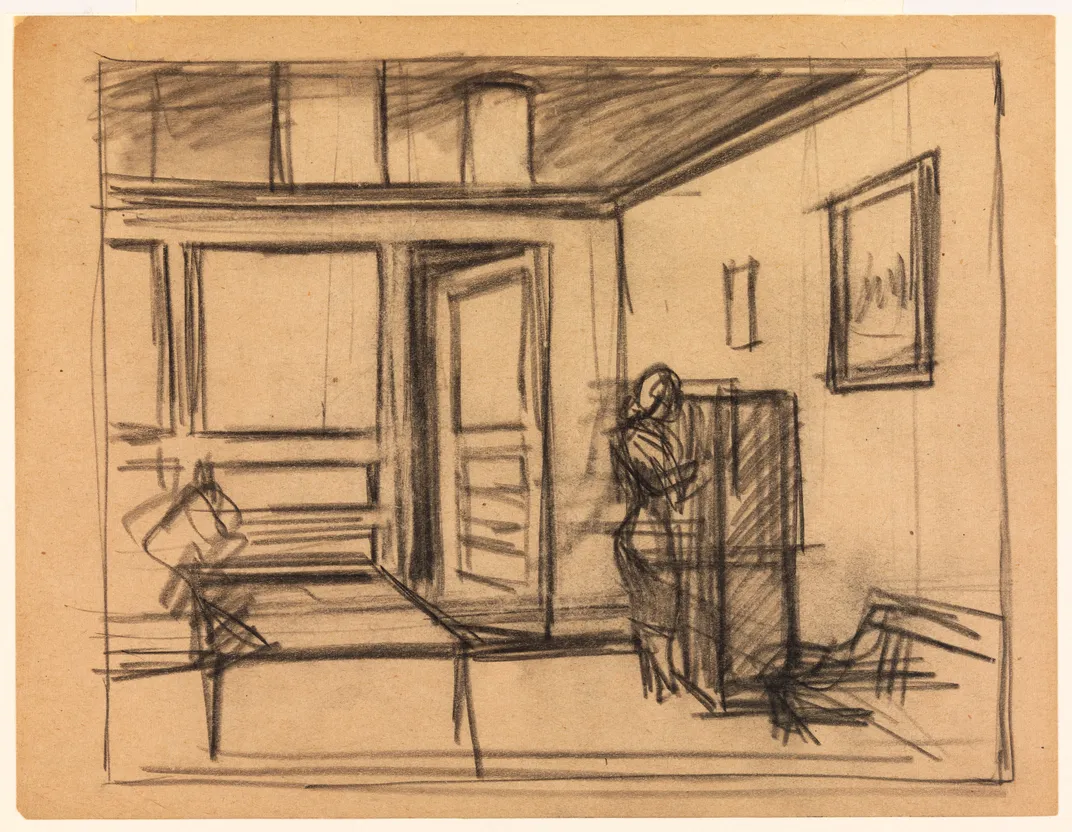

Other clues about how Hopper created this unsettling sense of drama are provided by the preparatory chalk drawings in the show. By following these drawings from earliest to latest, we can watch over Hopper’s shoulder as, step by step, his imagination transforms the scene. He begins with a straightforward rectangular room, where the secretary stands, relaxed, next to the filing cabinet, and a large painting hangs on the wall. As the drawings progress, he gradually rotates the room, tilts the viewpoint, adjusts the light, experiments with the positions of the man and the woman to arrive at those frozen positions, and finally (in the finished work) removes the painting from the wall and adds the stray piece of paper on the floor between them. By the time we reach the finished painting, it’s as if we are watching a drama that refuses to unfold. As Schultz says: “There’s so much hanging in the air.”

All of the other paintings in the Hopper Drawing exhibit are given this same eye-opening analytic treatment, helping us understand why the artist’s “realistic” images have so much impact. At first glance, for example, Hotel Lobby (1943) looks pretty straightforward; but there is a subtle, yet palpable, sense of intensity among the three people in that lobby. Again, the many preparatory drawings show us that we’re not imagining it; every detail was submitted to the artist’s imagination to convey that reaction. Similarly, in the elevated view of sunlight-raked buildings in From Williamsburg Bridge (1928), the solitary figure in a window, which evokes a vague sense of loneliness, is a late addition to the composition. Or consider Rooms for Tourists, a Victorian house in Provincetown, where Hopper spent his summers. It’s just plain spooky. Hopper parked his car so often near that house, sketching every detail, that the people inside wondered what was going on; and then, in the final painting, he shrouded the house in darkness. As art critic Robert Hughes wrote in his book American Visions, “Hopper’s isolated Victorian houses, with their porches and pediments and staring windows, were recycled by a host of illustrators and filmmakers: the house the comically sinister Addams family lived in is a Hopper house, and so is the mansion alone on the Texas prairie in Giant, and the house in Hitchcock’s Psycho.”

Yet, even with all these insights into Hopper’s creative process, we’ll never fully understand all the mysteries his paintings hold, which brings us back to the novella that has just been written for Office at Night. “What was very interesting for me is that both writers approached their process in the way that Hopper approached his process, which is starting with the facts of the painting and then improvising from there. You’ll see that when both Laird and Kate write, some of the elements that are missing in the painting, but that are in the drawings, actually have a role in the story.”

For example, Schultz reveals, the painting that hung on the wall in the preparatory drawings—but didn’t make it into the final painting—plays an important role in the story. Hmm…lost? Stolen? You’ll have to read the installments on the museum’s website to find out. But Schultz offers one last teaser. “The writers develop a backstory for the characters and the woman has this whole obsession with filing,” she says, and, after reading the novella, “I’ll never feel the same way about filing cabinets again!”

"Hopper Drawing: A Painter’s Process" is on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis through June 22, 2014. The exhibition was organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalog, Hopper Drawing, published by Yale University Press. The novella inspired by Office at Night will eventually be published as an e-book by Coffee House Press.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/bond.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/5d/ea5d0a2e-b82b-4061-96a0-8068f96c0911/01_wac_office-at-night_c.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cd/9c/cd9c16b9-63e0-4156-959e-4a54fce3666a/03_70_166a_cropped.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/e1/43e1d72d-70d1-40ab-bdec-97a6fac4dd3f/05_70_341_cropped.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/49/6349b1a2-3463-4958-98ad-bf23e5366f1a/06_70_340_cropped.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/3f/7a3f2c70-4acc-4933-a21b-1ccff65835e9/08_70_996_cropped.jpg)