A Brief History of Traveling With Cats

Fierce felines of history sailed the world, survived Europe’s crusade against them and made it all the way to Memedom

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/27/bc275e34-f2d3-4f90-b18f-b1bda8e4af3e/vladimir1_low_res.jpg)

My three-year-old cat spends most of her time lounging by the window. It faces the high branches of the tree outside our apartment, and she stares intently out at the rusty-red wood thrushes and brown house sparrows that perch there, her eyes dilating when the occasional squirrel rustles the branches.

She’s a seventh-floor housecat who longs for the outdoors. But even if there was a feasible way of letting her go outside, I wouldn’t let her loose on native wildlife on her own (if you’re not familiar with the war being waged between cats and birds, my colleague Rachel Gross has chronicled it in all its gory detail here).

So, as a compromise, last year I bought her a leash. After some initial hiccups, we have settled into a rhythm where I buckle her into her harness, scoop her up and carry her down to the soft grass adjacent to a nearby duck pond. There, I let her down, and her whims dictate our path.

Often, people stare. Sometimes, they’re walking their dogs: big ones, small ones. They squint at my cat, trying to decipher if perhaps she, too, is just a poorly shaped one of them.

She’s not. She’s a cat on a leash, and she’s not alone.

Earlier this summer, Laura Moss, a human at the center of a community helping introduce housecats to the outdoor world, published a book, Adventure Cats, bringing awareness to some remarkable cats who are out there hiking, camping—even surfing.

Moss, who also runs a website by the same name (adventurecats.org), explains that this kind of cat is far from a new phenomenon. “People have been doing this with their cats long before social media existed,” she tells Smithsonian.com. But in recent years, the community has received new recognition, she says, in large part thanks to people sharing photos and videos of their furry friends on various media accounts.

It’s not exactly surprising that it took the internet (which, undeniably, has done much for cats) to bring new awareness to this kind of anti-Garfield feline. While cats have been arguably unfairly stereotyped—as anti-social, afraid of water, lazy—history contradicts that narrative.

“From their beginnings in Egypt, the Middle East, and Europe, domestic cats have accompanied people to almost every corner of the globe,” write Mel Sunquist and Fiona Sunquist in Wild Cats of the World. “Wherever people have traveled, they have taken their cats with them. Geographic features such as major rivers and oceans that are barriers to most animals have the opposite effect on cats. Almost as soon as people began to move goods around on ships, cats joined ships' crews. These cats traveled the globe, joining and leaving ships at ports along the way.”

While evidence of domestication dates back at least 9,500 years (originating from the wild cat Felis silvestris lybica), it wasn't until the Egyptians got their hands on the felines that they became intensely documented. As early as 2000 B.C., Egyptian-made images of cats offer evidence that some of the earliest domestic cats were put on leashes. (Ancient Egyptians used cats to control their vermin population, and likely, these leashes were used so that their valuable pest control solutions wouldn't escape.)

Cats proved so apt at their duties that the Egyptians linked the ratters to their religious deities. By 525 B.C., cats were so revered that legend has it the Persians were able to invade Egypt in part by having soldiers bring cats to the battlefield. The Egyptians, the story goes, chose to flee rather than harm the animals.

Though it was illegal in ancient Egypt to export domesticated cats, people snuck a few out, and cats began to spread throughout world, with the earliest record of a domestic cat in Greece coming from a 500 B.C. marble carving of a leashed cat challenging a dog.

But the rise of Christianity signaled a sharp change in the way cats were perceived. To counter their Egyptian associations with divinity, in 1233 A.D., Pope Gregory IX issued the bull Vox in Rama, which linked cats–especially black cats—with Satan, writes John Bradshaw in Cat Sense. For the next four centuries, cats faced gruesome deaths in Europe due to superstitious associations with witchcraft and bad luck. Still, despite the cat's poor reputation, its ability to keep rodent populations at bay on ships meant that even during this turbulent time, more and more domesticated cats were undertaking what Gloria Stephens in Legacy of the Cat calls “a widespread migration to seaports of the world."

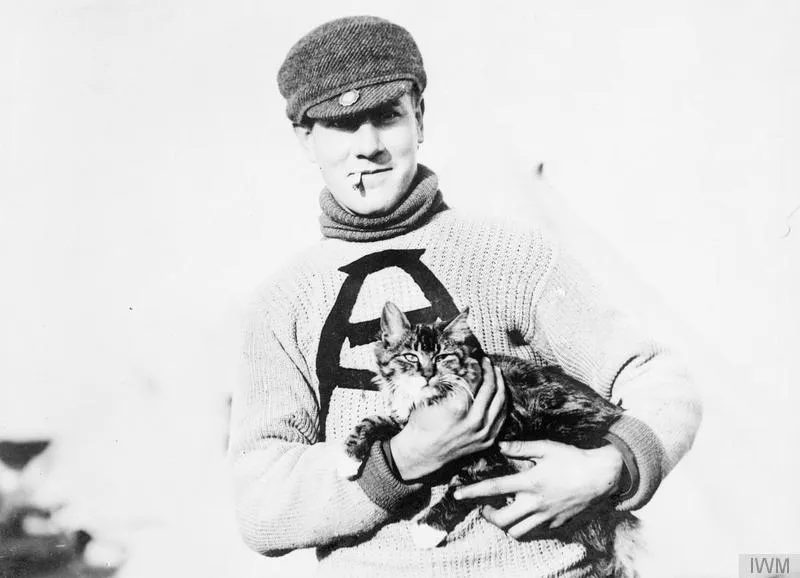

These adventurous cats didn't just keep cargo rodent-free, they also provided companionship to sailors and explorers, the U.S. Naval Institute notes. Mrs. Chippy, a tiger-striped tabby, for instance, witnessed Ernest Shackleton's ill-fated expedition to the Antarctic in 1914. The cat belonged to Harry "Chippy" McNeish, the carpenter on board the Endurance. As the crew soon found out, Mrs. Chippy was actually a Mr., but his name stuck and his personality soon endeared him to the crew. Unfortunately, Mrs. Chippy met a sad end. After the Endurance was caught in ice, Shackleton ordered that the crew reduce down to its essentials and had the men shoot Mrs. Chippy. Today, a bronze monument to the cat stands in Wellington, New Zealand, by McNeish's grave.

Other ship cat stories abound. Viking sailors took cats with them on long journeys, and if Norse mythology is any indication, Vikings enjoyed a healthy respect for their cat companions. (Freja, considered the greatest of all goddesses, employs two cats, Bygul and Trjegul, to pull her chariot. In her honor, it even became tradition among Vikings to gift a new bride with cats.)

Later, when the First World War broke out, cats found favor among soldiers who kept them for pest control, as well as company, on the battlefield. An estimated 500,000 cats served on warships and in the trenches. Mark Strauss details the "brave and fluffy cats who served" over at Gizmodo, highlighting felines like "Tabby," who became the mascot for a Canadian unit.

During the Second World War, one of many cat tales involved Winston Churchill, who famously took a shine to Blackie, the ship cat aboard HMS Prince of Wales. The large black cat with white marks, who was later renamed Churchill, kept the prime minister company across the Atlantic on his way to meet with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Newfoundland in 1941. (Controversially, some cat fans took issue with a shot snapped of the two, however, where the prime minister is pictured patting Blackie on his head: “[Churchill] should have conformed to the etiquette demanded by the occasion, offering his hand and then awaiting a sign of approval before taking liberties,” opined one critic.)

Even today, the tradition of the ship's cat sails on—the Russian Navy sent its first cat on a long-range voyage to the Syrian coast just this May. In modern times, though, ship cats are no longer are allowed to wander off seaports unchecked—a situation that once proved devastating to closed ecosystems.

Not until the mid-18th century, though, did the cat start clawing its way back to good graces in Europe. Bradshaw notes that France’s Queen Maria made the cat more fashionable in Parisian society, while in England, poets spoke highly of the felines, elevating their status. Then, during the late 19th century, cats found a champion: writer and cat lover Harrison Weir. Weir, considered the original Cat Fancier, created the first contemporary cat show in 1871 in England. (It’s considered the first contemporary show because technically the very first-known cat show was held at the St. Giles Fair almost 300 years earlier, but those cats were judged solely on their mousing abilities.)

“He had been distressed by the long ages of neglect, ill-treatment and absolute cruelty towards domestic cats had suffered, and his main objective in organizing the first show was promoting their welfare rather than providing an arena for competitive cat owners,” writes Sarah Hartwell in a “Brief History of Cat Shows.” One of the cats entered in the show was his own, a 14-year-old tabby named The Old Lady. The show brought cats back into the spotlight, celebrating them and raising their status as domesticated pets.

But just because cats were put on leash in these early exhibitions, that didn't mean they were also promenading around London.

“I wouldn’t say that putting cats on leashes was a particular fashion—at least, not one I’ve come across in my own research,” Mimi Matthews, historian and author of the upcoming book The Pug Who Bit Napoleon, tells Smithsonian.com in an email. “For cat shows, it was simply a practical way to restrain a cat when it was out of its cage.”

Still, thanks to the success of the cat show, the first cat association—the National Cat Club of Great Britain—was formed in 1887 (followed shortly by a national mouse club in 1895). It was around this time that the first "viral" images of cats circulated: An English photographer named Harry Pointer had graduated from shooting images of cats in natural settings to placing his "Brighton Cats" in amusing situations where the cats appeared to be riding a bicycle or drinking tea from a cup. His Victorian-era pet portraits reinforced the idea that cats could be seen as more than just pest control.

The transition from ratter to pampered housecat had a ways to go, though. As Abigail Tucker writes in The Lion in the Living Room: How House Cats Tamed Us and Took Over the World, until the mid-20th century, cats were still mostly used to eradicate rodents, something a journalist for the New York Times illustrates while chronicling his observations on daily life abroad in Moscow in 1921.

"The queerest thing I have yet met in this land where everything is so different and topsy-turvy is cats on leashes like dogs in the streets," he writes. That wasn't because Russians viewed the house pets similarly. Instead, as the reporter explains, the reason came down to rats: "There are so many rats nowadays, and cats are relatively so scarce, that they are too valuable to be allowed outside alone, so their owners give a good ratter an airing on a leash."

For the domestic cat to become the family pet, technology had to advance. The advent of cat litter in 1947 proved crucial, as did more effective pest-control methods that while not retiring cats from their centuries-old job, certainly made it less pressing. Of this shift from pest control to household companion, Tucker writes, “perhaps our firesides were as good a place to retire to as any."

But why were cats treated so differently than dogs when they took on their new role as companions?

It's true that dogs are much easier to take out for a walk. Domesticated roughly 13,000 to 30,000 years ago, they have been selectively bred for companionship. Domesticated cats came on the scene relatively recently by comparison, and as a cat genome sequencing project published in 2014 shows, modern cats remain only semi-domesticated, and because of that, training a cat to walk outdoors isn't as simple as snapping on a leash, something Jim Davis' Garfield comic strips pokes endless fun at. When Garfield's owner, Jon, tries to take the famed feline for a walk, Garfield repeatedly resists his efforts, until John comes to the conclusion in 1981 that leashes just aren’t right for cats.

Gender stereotypes might also play a role in why more haven't tried, though. Cats have historically read as female. In a study of greeting cards, Katharine M. Rogers links "[s]weet, pretty, passive kittens" with how girls and women were pressured to be in The Cat and the Human Imagination.

"They attend on little girls on birthday cards, and they fill in the image of home, whether they sit by the rocking chairs of nineteenth-century style mothers doing embroidery (1978) or perch on a pile of laundry that Mother should leave undone on Mother's Day (1968)," Rogers writes. Promisingly, however, she observes that contemporary cards have started to reflect a larger imagination for its subjects ("as women appear in nontraditional roles, cats are shown with men"), which could help fight the idea that the housecat's place is only in the home.

Of course, not all cats are made to roam the great outdoors. As Moss observes, cats are like humans. Some housecats are more than happy to spend their days relaxing by the couch, and indeed have no desire to venture outside.

But they're not the only cats out there.

The "adventure cats" that she chronicles, like a black-and-white feline named Vladimir, who is on his way to traveling to all 59 U.S. national parks or a polydactyl Maine Coon named Strauss von Skattebol of Rebelpaws (Skatty for short), who is sailing the Southern Atlantic ocean, show another kind of cat – one that nods back to the fierce felines of history who sailed the world, survived Europe's crusade against them and made it all the way to Memedom.

Unlike outdoor cats and feral cats, who pose a danger to local species populations in the wild, these cats are safely exploring the world. Their stories, which today are enthusiastically shared and liked on social media verticals, break open the role of the house cat—and show off a community of cats that have long been taking the world by the paw.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.