Trekking Hadrian’s Wall

A hike through Britain’s second-century Roman past leads to spectacular views, idyllic villages and local brews

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Newcastle-Church-High-School-student-walk-along-Hadrian-wall-631.jpg)

In A.D. 122, a few years after taking control of the Roman Empire, which reached its greatest expanse by the time of his rule, Caesar Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus Augustus trekked to the edge of the known world. It was a bold journey, one that few of his contemporaries cared to make. "I would not like to be Caesar, to walk through Britain," a waggish poet wrote at the time.

There's no way to be sure how long he stayed in Britain or what he did there, but Hadrian apparently left orders to construct one of the most formidable building projects the world had ever seen: a wall 15 feet high and up to 10 feet thick, stretching from sea to sea.

Hadrian's Wall has long attracted hikers and history buffs and is now the heart of an 84-mile-long National Trail that winds through some of England's most scenic countryside, following in the footsteps of Roman soldiers who once patrolled the empire's frontier. Not long ago, I set out to see Hadrian's monumental fortification, crossing England east to west in search of the island's Roman past.

I began in Wallsend, a town outside Newcastle, in the shadow of shipyard cranes, where a small museum of Roman artifacts marks the wall's eastern terminus at the River Tyne. In Roman days, there was a four-acre fort here called Segedunum ("strong fort" or "victory fort"); today, all that remains are a few of the fort's stone foundations and a carefully reconstructed Mediterranean-style bathhouse guarded by a few bored-looking men in legionary costume.

Across the street, I got my first glimpse of the wall itself. A few dozen feet of sturdy stonework faces a row of squat brown brick townhouses, then disappears into a suburban development. I followed the dashed purple line for the wall on my official map past warehouses and abandoned lots, across a tangle of overpasses, raised walkways and bridges, and into bustling downtown Newcastle. Here the modern trail hews to the Tyne, but I took a shortcut along the main highway, a busy six-lane thoroughfare that runs close to where the wall once stood. The Roman surveyors did a good job: the A186 heads west from Newcastle in a straight line, twisting and turning only to follow the ridgeline. The wall suddenly appears again for about ten yards on the city outskirts, in a parking lot between an auto parts store and Solomon's Halal Punjabi Indian Cuisine.

Planning the trip, I had assumed I could make 15 or 20 miles a day. After all, Roman soldiers in leather sandals are said to have averaged about that distance, with time enough at the end of each march to build a fortified camp. But for the first couple of days I limped into bed-and-breakfasts after about eight miles with blisters on top of my blisters.

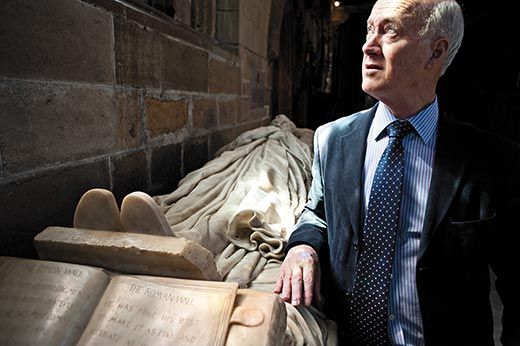

So on the third day I hopped a bus from Tower Tyne to one of the most important sites along the wall: Vindolanda ("white lawns," possibly after a native term), a Roman fort that predated the wall and covered four acres in Hadrian's day; it supplied and housed soldiers who manned the wall's 80 milecastles, akin to small forts, and 160 turrets. Robin Birley, 74, a stooped, bespectacled man proffering a muscular handshake, has been conducting an archaeological dig at Vindolanda for more than 50 years; his father began digging here in 1930, and Robin's son, Andrew, directs excavations at the site. The nearby house in which Robin Birley grew up is now the Chesterholm Museum, home to Vindolanda artifacts.

While digging a drainage ditch in 1972, Robin Birley punched through thick clay and found a large deposit of organic artifacts, including leather shoes, animal bones and wooden combs—all preserved by wet, oxygen-poor soil. Most important, Birley and his team have turned up almost 1,400 thin wooden writing tablets, inked in Latin, from A.D. 85 to 160. There are military documents, lists of kitchenware and other ephemera, including the oldest known examples of women's writing in Latin. "On the third day before the Ides of September, sister," to cite one letter, "for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival."

The tablets reveal an army concerned with order and minutiae, from requests for leave to beer inventories. "The documentary evidence is unbeatable," Birley said. "It's like listening in to private conversations."

At the height of Roman Britain, in the second and third centuries A.D., 15,000 troops and engineers were stationed along the wall, and another 15,000 to 18,000 legionaries were elsewhere in Britain; together, they made up one of the largest imperial forces outside of Rome. Still, few histories from the period survive—and those that do focus more on politics in Rome than battles on the periphery. "There's practically a whole century without any reference to what was going on in Britain at all," says David Breeze, a Scottish archaeologist and author of the latest edition of J. Collingwood Bruce's Handbook to the Roman Wall. "Apart from the Vindolanda tablets, we have enormous gaps, and we're never going to fill them."

But a biography written more than 200 years after Hadrian's death links the emperor to the wall: "Hadrian was the first to build a wall, 80 miles long, to separate the Romans from the barbarians."

One thing that is clear is that the wall was built at the end of an extraordinary period of expansion. From its earliest days, the Roman army had a hard time staying put. Led by generals hungry for glory—and perhaps a shot at becoming emperor—the legions constantly sought new conquests. From the first century B.C., a string of ambitious leaders pushed the boundaries of the empire steadily outward, to Britain and elsewhere. Julius Caesar crossed the English Channel in 55 B.C. and returned a year later. In A.D. 43, Claudius invaded England near Richborough, in Kent, and his successors pushed the island's Roman frontier north. By the end of the first century, Roman troops had forced their way deep into what is now Scotland. Trajan, crowned emperor in A.D. 98, fought wars in Dacia (present-day Romania), Parthia (Iran) and Germania.

When Trajan died in 117, his protégé Hadrian—an experienced military commander born into a prominent family, who spoke Greek, wrote poetry and took an interest in philosophy and architecture—inherited an empire and an army stretched to the breaking point. "He realizes they've expanded too far, too fast," Birley said. "Somehow he has to get the message across: ‘This far, no farther.'"

In 122, Hadrian visited Britain, and though his exact itinerary isn't known, historians believe that he toured the frontier. What better way to define the edge of his empire and keep his army out of trouble, the emperor-architect might have decided, than a monumental stone wall?

After a night at Greencarts Farm, just west of Chollerford, the morning dawned gray and cold. As I sat on the porch taping my bruised feet and lacing my muddy boots, the landlady brought the bill. "Just remember, there's always the bus," she said. Her accent rounded "bus" into a gentle "boose." I headed out through the farmyard into a drizzle, weighing her words carefully.

My spirits picked up almost immediately. At the edge of the farm, the wall reappears, rising to five or six feet in some spots. I soon climbed out of the low, rolling farm country to the top of the Whin Sill, a jagged ridge jutting hundreds of feet above the valley. It's lined with unbroken stretches of wall for miles at a time. Over the next two days, the wall was an almost constant presence. This center section, roughly ten miles long, remains the most rural, unspoiled and spectacular part of the walk.

At mile 36, I came upon Housesteads, a five-acre fort known to the Romans as Vercovicium ("hilly place" or "the place of effective fighters"). Draped over the lush green hillside, its extensive ruins were excavated more than a century ago; even so, the site is daunting. This was no temporary outpost: the commander's house had a courtyard and a heated room, the fort's latrines had running water and there was a bathhouse for the troops.

West of the fort, the wall climbs to Highshield Crags. Following the wall as it runs steeply up and down took my breath away. One can hardly imagine the ordeal the builders endured dragging the stones, lime and water up these rugged peaks—a ton of material for each cubic yard of masonry. The wall, according to some estimates, contains more than 1.7 million cubic yards.

Atop the ridge at least 100 feet above the valley and barricaded behind their stone wall, Roman soldiers must have gazed north with a sense of mastery. An earthwork consisting of a ditch 10 feet deep and 20 feet across and with two mounds on either side, known as the Vallum, ran just south of the wall, where there was also a wide road to move troops from one post to the next. On long stretches of the wall's north side, another deep ditch posed yet another obstacle. In some places the ditches were carved out of solid bedrock.

What were the Romans so worried about? Breeze says the Roman frontier wasn't primarily about defending the empire against barbarian attacks, as some archaeologists have argued. "Built frontiers aren't necessarily about armies attacking, but about controlling the movement of people," he says. "The only way you can fully control things is to build a barrier." Used for administrative control, not warding off invasion, it funneled people through designated access points, such as the gates that appear at regular intervals along the wall. The wall, he suggests, was more of a fence, like the one that runs along parts of the United States-Mexico border.

Even so, the wall also served to keep out not just "casual migrants" but enemies, says Ian Haynes, an archaeology professor at Newcastle University. In the past decade, excavators have turned up extensive pits that had held posts, possibly for sharpened stakes, fronting parts of the eastern section of the wall. "The kind of effort that goes into these defenses isn't just for decorative purposes," says Haynes. "It's wise to think that they were doing this in deadly earnest." Archaeologists have long searched for traces of the tribes who lived north of the wall, partly to assess the threats the Romans faced.

After breakfast of beans and toast in the town of Twice Brewed, I again headed to the top of the Whin Sill, where the route goes up and down rocky crags. Cresting the trail's last big hill late in the afternoon, I saw the sunlit roofs of Carlisle, a town about ten miles to the west. Looking to the south across the (aptly named) Eden Valley was like paging through a picture book of 19th-century England. Cottages were tidily tucked among green-grid pastures threaded by wooded lanes. On the far side, a train chugged west.

A few miles on, I reached the village of Walton. After 18 miles of hiking, my only concern was getting off my feet. I unhooked a metal cattle gate and walked up a muddy path to Sandysike Farm. Built in 1760—probably with stones filched from the wall—the white farmhouse straddles the line of the wall, and the path runs along the back fence. Richard Sutcliffe, the owner, greeted me at the gate and led me into his messy, concrete-floored kitchen, where a three-legged black Lab, two Jack Russell terriers and four Jack Russell puppies competed for attention.

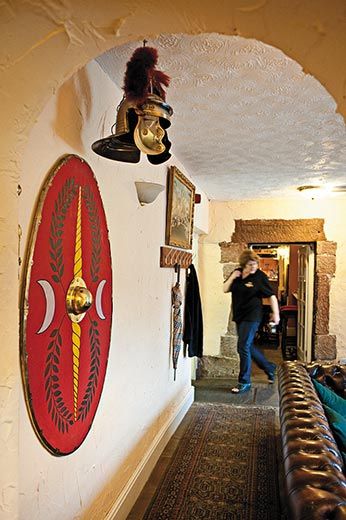

Over a mug of tea, Sutcliffe said that the new walking trail has been a blessing for the farms and towns along the wall's path. "It's harder and harder to make farming pay these days," he said. A few years ago, Sutcliffe and his wife, Margaret, converted an old stable into a bunkhouse. Between May and mid-September, the Sutcliffes are booked nearly solid; some of the hikers I met along the trail had made reservations nine months in advance. (To prevent erosion of the trail, authorities discourage visitors from walking it in the rainy season, from November to April.) Lured by the promise of Cumberland sausage made from local pork and a beer or two, I gingerly pulled my boots back on and headed up the road to the Centurion Inn, part of which stands atop the site of the wall.

In the six years since the Hadrian's Wall trail was designated a national landmark, more than 27,000 people have walked it from end to end. Some 265,000 hikers spend at least a day on the trail each year. Unesco has designated Hadrian's Wall and the ancient Roman border in Germany as part of a larger World Heritage site, the Frontiers of the Roman Empire; archaeologists and preservationists hope to add sites in other nations to outline the empire at its greatest.

Traveling the course of Hadrian's great fortification over six days, I got a sense of how the wall defined what it was to be Roman. Between Wallsend and Bowness-on-Solway, the western terminus, a line was drawn: Roman citizens and other cosmopolitan residents from across the empire on one side, barbarians (as the Romans termed everyone else) on the other.

On my last day, I crossed wide stretches of windy, flat fields and marshlands and munched on the last blackberries of the season as I headed to Bowness.

A white gazebo overlooking the Solway River marks the finish—or, for some, the start. A carved sign over the entrance reads "Wallsend 84 miles." A retired British sailor in an argyle sweater stood under the hut's roof. "We're at the end of the world out here," he said with a smile.

Berlin-based Andrew Curry last wrote for Smithsonian about Gobekli Tepe, a Neolithic temple in Turkey. Photographers Sisse Brimberg and Cotton Coulson live in Denmark.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)