A Long-Forgotten, Underground Tunnel in D.C. Is Finally Getting Some Fresh Air

The 75,000-square-foot space underneath the city’s Dupont Circle will become an impressive new art space

About eight feet below the surface of one of the busiest neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., lies a massive series of tunnels. Snaking their way under Dupont Circle and beyond, these dark, concrete passageways and platforms take up about 75,000 square feet of space. Over the past 50 years, with one ill-fated exception, they have lain pretty much unused, forgotten and ignored. The Dupont Underground project is trying to change that, with the hope of turning the tunnels into a place where art thrives.

The first electric streetcar appeared in Washington, D.C., in 1890. Drawing power from overhead electric wires and, later, ground rails, the cars zoomed around the city, providing a faster and cleaner alternative to the horse-drawn transportation of the past. The streetcars were very popular into the 20th century, but the system soon became congested and plagued by delays and breakdowns. As early as 1918, Congress issued a report attempting to find ways to alleviate these issues. Despite the problems, commuters continued to use the streetcar system; by the post-World War II era, the congestion had become so bad—especially in the even-then-trendy Dupont Circle neighborhood—that improvements had to be made.

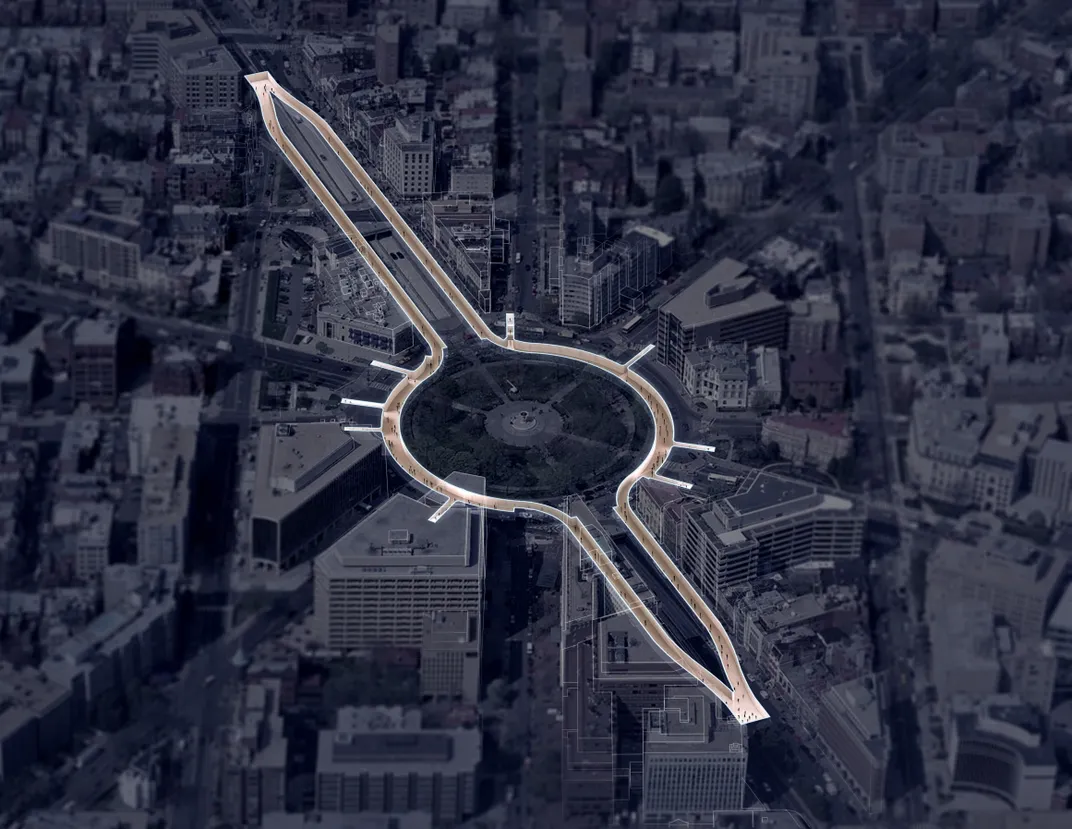

The city’s solution? Bring part of the system underground. In 1949, Capital Transit and the city worked together to build a trolley station, platforms and tunnels below Dupont Circle, extending from right above N Street to R Street, where the tunnels connected to the rest of the above-ground streetcar system. While the solution helped to alleviate traffic in the circle and surrounding area, it didn’t last long. In 1962, only 13 years after the underground portion opened, the entire streetcar system shut down due to declining ridership, labor strife and the rise of America’s car culture. Today, the District is trying to revive the streetcar system, albeit in a different area of city, though the opening has been delayed several times.

Since 1962, this vast, unoccupied subterranean space has hardly been touched. In the 1970s, parts of the tunnels were a fallout shelter, but according to Agnese, the site was used mostly for storing supplies—water, rations and equipment—rather than as a gathering point for people. In 1995, the “Dupont Down Under” transformed the west platform of the Dupont underground station into a food court, which left a bad taste in everyone’s mouths (literally). The project included 12 tenants, all of the fast food variety, and had problems right from the start.

“Apparently the ventilation failed within the first month and the place didn’t smell good ... I know people who went down there during summer months and it just was not pleasant,” said Agnese. It later emerged that the project’s chief architect, entrepreneur Geary Stephen Simon, had been convicted several times for fraud and other business crimes and had spent time in jail. (District officials maintained they were unaware of Simon’s history when granting him the lease.) Within months, lawsuits were being filed against Simon for failing to pay bills on the project totaling upwards of $200,000. In less than a year, “Dupont Down Under” closed, leaving the entirety of the tunnels empty once again.

Unlike the food court attempt, Dupont Underground isn’t trying to transform the space—instead, they are trying to adapt to it.

Architect Julian Hunt moved to the D.C. area from Barcelona over a decade ago. After hearing about the massive, unused space, Hunt saw it as a chance to develop the city's architectural identity. Said Agnese, “Julian started this all driven out of architecture passion ... there was a very robust architecture design scene in Barcelona that was very involved in the life of the city. He didn’t find that when he came to D.C. … He saw [the Dupont Circle tunnels] as a space to facilitate that kind of conversation and activity that wasn’t going on here yet.” Using Düsseldorf’s Kunst im Tunnel (a contemporary art museum underground), the Brunel Museum Thames Tunnel and even New York’s above-ground railway High Line as inspiration, Hunt started formulating a plan for using these tunnels to turn D.C. into a cultural capital and a “world-class city.”

After sharing his vision of art and culture underground, Hunt brought others on board, including Agnese. The Dupont Underground, which officially formed as nonprofit under a different name in 2003, recently secured a 66-month lease from the District. The short-term plan is to open the former Dupont Station’s east platform by July, and the intention is to open the west platform within a year. When the lease is up, the nonprofit hopes to negotiate a long-term agreement with the city and begin work to “activate” the rest of the 75,000 square feet of tunnels.

In March, the organization was able to raise enough money (about $57,000) through crowdfunding to open the east platform to a limited capacity this summer. Their plan for the east platform is, refreshingly, not overly ambitious. The coalition wants to keep it a “raw space with minimal amenities” in order for the station to “retain the historic character it has today.” While nothing has been made official yet, the nonprofit is in talks with musical performers, theater groups, and the creators of experimental art installations, while also hoping to eventually attract commercial photography, film and television shoots.

As for the larger west platform, the former home of “Dupont Down Under,” Agnese says: “The one saving grace that the food court existed at all is that it gave us infrastructure. It’s got the power, water, sewer lines, sprinkler system, and we may even be able to salvage the AC.” The plan is turn the west platform into a main event space, with enough room to fit 500 to 1,000 people. The organization is now mounting a larger capital campaign—targeting philanthropic, corporate and sponsorship dollars—to help make that happen.

Much like their European counterparts, as American cities age and grow, there’s often less and less room to build up and out. In some cases, the best solution for the space problem may be to aim down. Plus, as Agnese points out, being below the surface has always been part of the human experience: “Underground spaces have a long history in the psyches of humans as both points of attraction and mystery ... there’s this great tension.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.