Can Underwater Art Save the Ocean’s Coral Reefs?

Artist Jason deCaires Taylor is creating sculptures to help promote reef growth

Over the course of 12 years, Jason deCaires Taylor's wanderings as a paparazzo, a diving instructor, and a theatrical set designer had left him filling unfulfilled and disconnected from the artistic life he had envisioned for himself during art school -- and the oceans he fell in love with during his childhood in Malaysia. So he made a change, buying a small diving center in the Caribbean to support a renewed focus on his art. What he soon discovered was that his two seemingly different passions—art and the ocean—weren't mutually exclusive.

"The intersection of art and the ocean struck me as being excitingly unexplored terrain," deCaires Taylor wrote in the foreword to a new book of his work, Underwater Museum. "I quickly realized that my passion was not for teaching scuba diving but for creating art that would facilitate marine life."

Though shallow seas constitute only eight percent of the world's oceans, they're thought to contain the majority of marine life—life that is under constant threat from the disappearance of coral reefs, thriving ecosystems that house thousands of marine species (25 percent of all marine life, by some estimates). The decay of coral reef environments is caused in part by ocean acidification, which has increased 30 percent since the start of the Industrial Revolution. As the ocean absorbs the skyrocketing levels of human-made carbon emissions, almost 40 percent of coral reefs have disappeared within the past few decades—and scientists warn that nearly 80 percent could be gone by 2050.

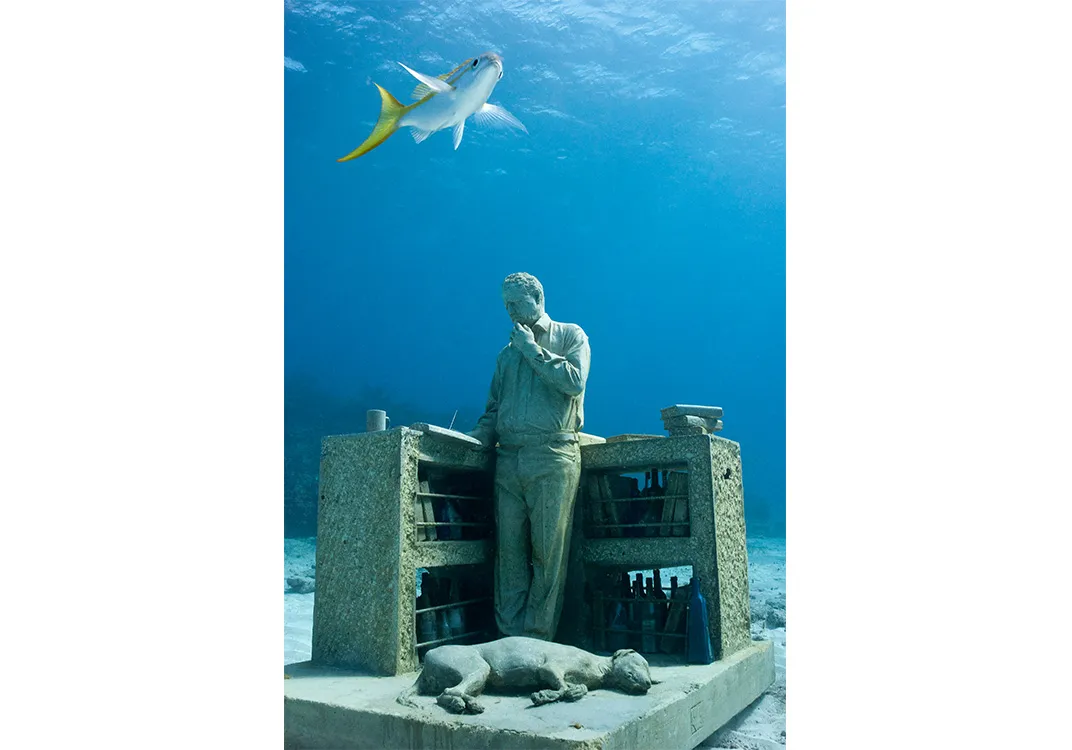

Much of the ocean floor is too unstable to support a reef, so deCaires Taylor has created artificial reefs—statues placed anywhere from four to nine meters underwater—to encourage ecosystems to take hold and flourish. The statues are almost as diverse as the ecosystems they hope to foster. Some, like The Silent Evolution or Vicissitudes, depict groups of people standing, some looking toward the sky, some gazing down at the ocean floor. Others, like Un-Still Life (off the coast of Grenada), show inanimate objects—a table, a pitcher, a few stones—waiting to be reclaimed by nature. Inertia, sunk four meters deep in Punta Nizuc, Mexico, features a sloven, shirtless man with a half-eaten hamburger watching television—an attempt to immortalize humanity's apathy toward global warming, deCaires Taylor says. Still, the statues are as practical as they are symbolic: a Volkswagen beetle featured in Anthropocene may serve as an artistic comment on fossil fuel consumption, but its hollow interior acts as a very practical living-space for crustaceans such as lobsters.

They act as a stable base on which artificial reefs can form. Creating artificial reefs benefits marine life in two ways: by creating a reef system for life to thrive in, and by taking pressure off of natural reefs, which have been over-fished and over-visited. deCaires Taylor's underwater statues promote algae growth, which in turn helps protect coral from bleaching, a consequence of warming waters that places fatal stresses on the coral. Algae can be seen growing on installations such as Vicissitudes, found off the coast of Grenada, a work that depicts a circle of children holding hands—symbolic, deCaires Taylor says, of the cycle of life. To date, deCaires Taylor has created hundreds of underwater statues in waters from Mexico to Spain.

In many ways, deCaires Taylor's goal of promoting reef growth dictates his art: the sculptures are all made from marine-grade cement that is completely free of other substances, such as metals, that could be harmful to marine life; the material has proven to be the most useful substance in the support of reef growth. deCaires Taylor also leaves patches of rough texture on his sculptures to help coral larvae gain a strong foothold. He also considers marine life promotion when sculpting the curves and shapes of the statues, factoring in crevices and gaps to allow fish and other life to duck in and out of their new cement homes. In The Silent Evolution, an installation off the coast of Mexico that features 450 statues, the human figures create a sort of shelter for schools of fish—snapper often hover close to the figures, darting to shelter under their legs when a predator, such as a barracuda, swims by. The installation's locations are also carefully chosen—when possible, the statues are placed downstream of a thriving reef in order to catch coral larvae and other marine life floating by.

The statues are formed above ground and thoroughly washed to remove any potentially harmful chemicals. Then, the statues are hauled to the ocean, using lifting rigs made specially for the statues, to help prevent damage. Once the statues are carried to sea, they are carefully sunk into their final marine resting place. To place deCaires Taylor's The Silent Evolution, which is comprised of 450 human figures, a forty-ton crane was places on a commercial car ferry. Some statues, like the Volkswagen beetle that is part of deCaires Taylor's Anthropocene, are so heavy that they have to be sunk into place using special lift bags—bags of air that help control the position of the statue as it sinks below the ocean's surface. Once the statues reach the seafloor, they are drilled into place using pilings and specialized marine hydraulic drills. To place the first installation off the coast of Grenada, deCaires Taylor had get the green light from the island's Ministry of Tourism and Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Beyond attracting marine life, the artificial reefs attract humans as well, drawing crowds of divers and snorkelers away from natural reefs, which can easily be damaged by a clumsy diver. One of deCaires Taylors installations is even located within easy swimming distance from one of the world's most popular dive sites near Punta Nizuc in Cancún. That said, once a part of the ocean's ecosystem, the sculptures are vulnerable to some of the same threats; divers and snorkelers who visit the sculptures must still avoid bumping or touching the reefs, which could damage their ability to grow.

To visit deCaires Taylor's work in person, travelers can find statues near the Manchones Reef in Mexico, off the coast of Grenada near Molinere, by Punta Nizuc in Cancún or at Musha Cay, in the Bahamas. To experience deCaires Taylor's work without booking a ticket to these exotic locations, check out the newly published collection of his work The Underwater Museum: The Submerged Sculptures of Jason deCaires Taylor, published by Chronicle Books.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)