Welcome to the World’s Only Museum Devoted to Penises

In Iceland, a man has collected 283 preserved penises from 93 species of animals—including Homo sapiens

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Penis-museum-631.jpg)

In 1974, at the age of 33, an Icelandic history teacher named Sigurður Hjartarson was given a penis.

It was a dried bull’s penis, long and limp—the kind often used in the Icelandic countryside to whip farm animals—and a colleague of Hjartarson’s gave it to him as a joke at a holiday party after hearing how Hjartarson had one as a boy. Soon, other teachers began bringing him bull penises. The joke caught on, and acquaintances at the island’s whaling stations began giving him the severed tips of whale penises when they butchered their catch.

“Eventually, it gave me an idea,” Hjartarson told me when I recently met him in Reykjavík. “It might be an interesting challenge to collect specimens from all the mammal species in Iceland.”

It took a while, but given enough time, true dedication trumps all obstacles. Over decades of meticulous collecting and cataloguing, Hjartarson acquired 283 members from 93 different species of mammals, housing them in what he’s dubbed the Icelandic Phallological Museum. He finally achieved his goal in 2011, when he acquired the penis of a deceased Homo sapiens. In doing so, he’d assembled what must be the world’s most complete collection of male sex organs.

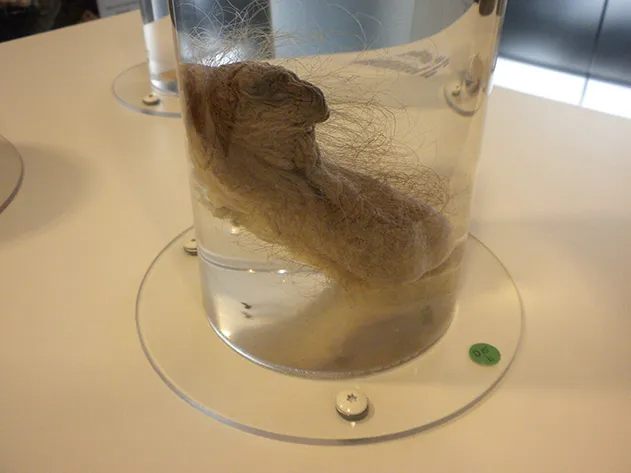

Anyone in the capital city of Reykjavík with 1250 Icelandic Krona to spare (about $10) can see the collection, now housed in a modest street-level space on a busy corner downtown. In the carpeted room lined with wooden shelves, Hjartarson packed an overwhelming number of specimens, mostly preserved in formaldehyde and displayed upright in glass jars. Among the collections are dozens of giant whale penises; tiny guinea pig, hamster and rabbit penises; wrinkled, grey horse penises; and a coiled rams’ penis that looks unsettlingly human. Some are limp, resting against the sides of their jars, while others seem to have been preserved in an erect state.

The walls are decorated with dried whale penises, mounted on plaques like hunting trophies, along with tongue-in-cheek penis-themed art (a sculpture of the silver medal-winning Icelandic Olympic handball team’s penises, for instance) and other penis-based artifacts, like lampshades made from dried bull scrotums. The museum’s largest specimen, from a sperm whale, is nearly six feet tall, weighs about 150 pounds, and is kept in a giant glass tank bolted to the floor. Hjartarson explained to me that this was merely the tip of the whale’s full penis, which couldn’t be transported intact when the creature died, and was originally about 16 feet long, weighing upwards of 700 pounds.

Talking about his peerless shrine to the male anatomy, Hjartarson is modest—he considers himself a conventional person—and seems as bemused as anyone that he’d pursued an offbeat hobby to such extreme lengths. “Collecting penises is like collecting anything else, I guess,” he said. “Once I got started, I couldn’t stop.”

Over the first few decades of his collecting, he did it on the side, continuing work as a teacher and then school principal in the town of Akranes on Iceland’s southwest coast. By 1980, he had 13 total specimens: four large whale penises, along with nine from farm animals, brought to him by friends who worked at slaughterhouses. Though he’d simply dried the penises to start, he began preserving them in formaldehyde so they’d more closely retain their original appearance. Over the decade, his collection grew slowly: by 1990, he’d amassed 34 specimens. After the 1986 international ban on commercial whaling, Hjartarson would drive several hours to the coast in hopes of a whale penis when he heard about an animal’s beaching on the news. The responses he got from friends and family, he said, were “99 percent positive,” if a bit perplexed. “This is a liberal country,” he explained. “When people saw that my collection wasn’t pornographic, but for science, they didn’t have a problem with it.”

By August of 1997, when Hjartarson had acquired 62 penises (including those of seals, goats and reindeer), he decided to share his obsession with the public, setting up shop in a spot in Reykjavík and charging a small entrance fee. As news of the museum spread, it began attracting a few thousands visitors a year, and some came bearing gifts: a horse penis, a rabbit penis, a bull’s penis that was salted, dried and made into a three-foot tall walking stick. In 2004, after Hjartarson retired, he briefly moved the museum to the fishing village of Húsavík and advertised it with a giant wooden penis outside. In 2011, his health failing, he convinced his son Hjörtur Gísli Sigurðsson to take over day-to-day operations as the curator and the duo moved the collection (then more than 200 specimens strong) to its current location. They say it now attracts roughly 14,000 people annually, mostly foreign tourists. On growing up as the son of the guy who collects penises, Sigurðsson told me, “Some of my friends joked about it, maybe a little, but eventually they got into it too, and wanted to help us collect them.”

The strangest thing about the museum: If you entered it, but couldn’t read the labels or signs, it’s very possible you wouldn’t realize what organ filled all the jars around the room. Most of them look less like the organs we’re used to and more like abstract flesh art, with wrinkled foreskins peeled back and floating in the liquid. At times, I couldn’t help but feel grateful for the glass that protected me from these grotesque folded lumps of meat. The jars of small penises—like the hamster’s, with a magnifying glass placed in front of it so you can see the tiny member—resemble some strange apothecary’s tinctures, arranged carefully on wooden shelves. During my time there, roughly a dozen tourists visited, talking in hushed voices as they browsed.

Though it was difficult for him to stand for extended periods of time, Hjartarson insisted on giving me a guided tour of his collection, walking with a cane. In the “Foreign Section” (filled with specimens from animals not native to Iceland), we found some of the museum’s most exotic specimens: a massive giraffe penis, stark white and adorned with a cuff of fur at its base and mounted on the wall, a dried elephant penis of a frankly startling length and girth, from an animal that had apparently been killed on a sugar plantation in South Africa and was brought to Hjartarson in 2002.

Hjartarson proudly pointed out a cross-section he’d had made of a sperm whale’s penis. “I had a biology student come here and tell me that this helped him better understand this species’ inner structure,” he said. The museum’s mission statement, after all, declares that it aims to help “individuals to undertake serious study into the field of phallology in an organized, scientific fashion.” Despite the kitschy penis art on the walls, Hjartarson appears to take this goal seriously.

Except, that is, for the glass room in the corner labeled, simply, “Folklore Section.” In it, Hjartarson has assembled (what he claims to be) the penises of elves, water horses, an Icelandic sea monster, a merman and a zombie-like bull. He refused to acknowledge the section’s silliness. When I asked him why there’s an empty jar labeled “Homo sapiens invisibilis,” he said, “What you can’t see it? It’s right in there.”

A highlight of the museum is in the back corner, where a shrine has been built to the collection’s human-related specimens. For years, Hjartarson said, he sought out a penis from Homo sapiens, and got several willing donors to sign letters ensuring their members would enter the collection after death. In 2002, Iceland's National Hospital gave him the foreskin of a 40-year-old Icelander who’d had an emergency adult circumcision, then, in 2006, he acquired the testes and epididymis from an anonymous 60-year-old. But he wasn’t satisfied.

Finally, in 2011, one of the letter-signers, a man named Pall Arason from the Icelandic town of Akureyri died, died at the age of 95. Hjartarson was particularly excited to get his penis—“he was a famous womanizer,” he told me—but the postmortem penectomy did not go well. Instead of being removed and sewn up shortly after death, it was allowed to shrivel, and the already age-shrunken penis wasn’t properly sewn up. In the glass tube, floating in formaldehyde, it’s an unrecognizable, disparate mess of flesh, rather than an orderly, compact shaft. “I still want to get a better, more attractive human specimen,” Hjartarson declared.

He has three more donation letters hanging on the wall—from a German, an American and a Brit who visited the museum and were moved to sign away their penises after death—but every year that passes makes them less valuable. “You’re still young,” he said, poking me in the shoulder forcefully, “but when you get older, your penis is going to start shrinking.” This quirk of the human anatomy puts him in the strange position of hoping that one of his potential donors perishes before they reach a ripe old age. Asked if he’d consider donating his own, Hjartarson told me the same thing he apparently tells all reporters: "It depends on who dies first. If my wife goes before me, I’ll have my penis go to the museum when I die. But if I go first, I can’t guarantee she’ll let that happen.”

Attractive human penis or not, the work of collection will go on, carried out largely by Hjartarson’s son. He said that he plans to collect better-preserved specimens for many of the Icelandic species, and expand the museum’s foreign collection—he’s specifically interested in hunting down the penises of many of Africa’s large predatory cats. “You can always get more, better, more diverse specimens,” Sigurðsson says. “The work of collecting never truly ends.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/joseph-stromberg-240.jpg)