Before Rosie the Riveter, Farmerettes Went to Work

During WWI, the Woman’s Land Army of America mobilized women into sustaining American farms and building national pride

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Newton-Square-Unit-Womans-Land-Army-631.jpg)

From 1917 to 1919, the Woman's Land Army of America brought more than 20,000 city and town women to rural America to take over farm work after men were called to war.

Most of these women had never before worked on a farm, but they were soon plowing fields, driving tractors, planting and harvesting. The Land Army's "farmerettes" were paid wages equal to male farm laborers and were protected by an eight-hour workday. For many, the farmerettes were shocking at first--wearing pants!--but farmers began to rely upon the women workers.

Inspired by the women of Great Britain, organized as the Land Lassies, the Woman’s Land Army of America was established by a consortium of women’s organizations--including gardening clubs, suffrage societies, women’s colleges, civic groups, and the YWCA.

The WLA provided a fascinating example of women mobilizing themselves and challenged conventional thinking about gender roles.

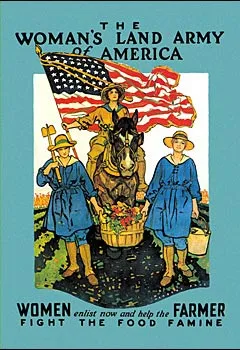

Like Rosie the Riveter a generation later, the Land Army farmerette became a wartime icon.

The following excerpt from Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army in the Great War chronicles the farmerettes of the California division of the Woman’s Land Army.

A brass band welcomed the first unit of the California Woman’s Land Army when it arrived in the town of Elsinore on the first of May, 1918. The whole community turned out to greet the fifteen women dressed in their stiff new uniforms. The Chamber of Commerce officials gave speeches of welcome, the Farm Bureau president thanked the “farmerettes” for coming, and the mayor gave them the keys to the city.

The Land Army recruits drove the fifty miles from the WLA headquarters offices in downtown Los Angeles to Elsinore in style: the mayor had dispatched a truck to chauffeur them. At the welcoming ceremonies, Mayor Burnham apologized for the lack of an official municipal key ring, and offered instead a rake, hoe, and shovel to the farmerettes, “emblematic of their toil for patriotic defense.” The grateful citizens of Elsinore gave the farmerettes three loud cheers.

While California fruit growers held lucrative contracts with the U.S. military to supply troops with dried and canned fruit, the extreme wartime farm labor shortage enabled the California Woman’s Land Army to demand extraordinary employment terms: a guaranteed contract, equal pay to what local male farm laborers could command, an eight hour day, and overtime pay. The employers also agreed to worker protections--comfortable living quarters, designated rest periods, lifting limits, and workers’ compensation insurance—considered radical for the time.

The Los Angeles Times trumpeted the arrival of the “Great Land Army” in Elsinore as an “Epochal Experiment” and proclaimed the farmerettes were “To Turn New Earth in History of the American Woman.” Photographs of the farmerettes’ first day at work, handling horse-drawn cultivators and gangplows, or at the wheel of giant tractors, were spread across the pages of the state’s newspapers. Asked if the strenuous labor might prove too hard, and some of the farmerettes might give up after a short stint, the recruits denied that was even possible. “Would we quit?” one farmerette told a reporter, “No, soldiers don’t.”

Idella Purnell didn’t lie about her age in order join the Northern California division of the WLA, which opened its San Francisco headquarters just a week later. She didn’t need to. The daughter of American parents, Idella was raised in Mexico but came north in preparation for entering university at Berkeley that fall. As a patriotic gesture, she wanted to serve in the Land Army in the summer months, but she was only seventeen years old, a year shy of the official entrance age. She passed her physical at headquarters, “and as I am ‘husky’ they decided to let my youth go unnoticed and simply make me 18!” Purnell confided, after the fact. The San Francisco recruiting officers were willing the bend the rules as they faced the prospect of trying to fill their large quotas; requests for more farmerettes were pouring in daily.

“This is the recruiting slogan of the Women’s Land Army of America,” reported one San Francisco area newspaper: “Joan of Arc Left the Soil to Save France. We’re Going Back to the Soil to Save America.”

An “advanced guard” of women, mostly Berkeley students, was sent to the University of California’s agricultural farm at Davis for training and soon proved themselves “extremely efficient and as capable as men workers.” Another unit was based in the dormitories of Stanford and worked the crops of the Santa Clara Valley in WLA uniform.

Sacramento set up a district WLA office, and more than 175 women enlisted for service in the first month. “Up in Sacramento they are nearly as proud of the WLA as of the new aviation field,” reported the San Francisco Examiner. “In both cases justification lies in actual achievement…the WLA shows that the women and girls are serious…and mean to do their bits.”

In mid- June on the eve of their deployment, twenty-four fresh recruits gathered in the San Francisco WLA headquarters, located in the Underwood Building on Market Street. They were the first group assigned to the brand new farmerette camp at Vacaville, and they were summoned together for a pre-departure pep talk.

The Vacaville Camp was constructed and furnished by a consortium of local fruit growers, who paid for it out of their own pockets. They built the camp on high ground near the Vacaville train station, with a six-foot high pine stockade surrounding it for privacy. Inside the stockade were canvas sleeping tents with wood floors, a screened kitchen and dining room, showers, and a dressing room, as well as a hospital tent. The camp cost about $4,500 to build and the growers agreed to share the investment: only those who contributed towards the camp were to enjoy the assistance of the farmerettes.

These farmerettes now assembled in the San Francisco WLA office, listening as their supervisor, Alice Graydon Phillips, explained what their life and work would be like in the Vacaville Camp. She warned them that the summer heat would be brutal, and that picking fruit atop ladders would make their backs, arms, and fingers sore.

She read them the Woman’s Land Army pledge and then asked aloud if they willingly would arise to the sound of a bugle at 5:30 in the morning? “Yes!” they shouted. Would they consent to the WLA military-style structure? “Yes,” they agreed in unison. Would they agree to muster for inspection, line up for exercise drills, take kitchen police duty, and eat the rations they were served without complaint? “Yes!” Would they submit to strict rules of discipline—including the provision that five offenses for lateness constitutes one breach of discipline and an honorable discharge? Here the “Yes” chorus was punctuated by some sighs, but they assented..

They signed the pledge forms. They elected two “majors” from their ranks to lead them—one, a girl who had four brothers fighting at the front; the other, an older woman from Santa Barbara with girl-club experience. Led by a college girl from Berkeley, they all joined in a rousing cheer:

Don’t be a slacker

Be a picker or a packer

WLA, Rah, rah, rah!

They took the early train to Vacaville, just beyond Napa, a journey of about sixty miles. “It was hot in the orchard at Napa,” Idella Purnell recalled.

The sun rose higher and higher, and the long ladders grew heavier and heavier. Perspiration started on our foreheads and beaded our lips. The golden peaches were so high—so hard to reach! The peach fuzz and dust on our throats and arms began to irritate the skin, but we did not dare scratch—we knew that would only aggravate the trouble. One who has never had “peach fuzz rash” cannot appreciate the misery of those toiling, dusty, hot-faced girls.

Purnell, who would make her career as a writer and editor of an influential poetry journal, was getting a crash course in the less romantic aspects of farmerette life. As word of their good work spread, more northern and southern California farmers asked for WLA units to be based near their orchards and ranches. The newspapers charted the farmerettes’ summons into the golden groves with headlines like: “Hundreds Go Into Fields at Once” and “Women to Till Thousands of Southern California’s Acres.” Sunset magazine carried an editorial in its July issue titled “The Woman’s Land Army is Winning” illustrated by a photo of farmerettes in uniform posing with hoes slung over their shoulders like guns.

The Los Angeles Times sent one of its star reporters, Alma Whitaker, to spend a day working with a Land Army unit, and she came away rather dazzled. Describing one farmerette as “tall and husky and wields a spade like a young Amazon her sword” and another as possessing “a pair of shoulders and muscular arms like a bantam lightweight” Whitaker was taken with the farmerettes’ serious attitude:

“This woman’s land army, composed of able-bodied young women, selected just as the men are selected by the army, for their physical capacity, their good characters, their general deportment, and trained and disciplined even rather more strictly than the men... are acquitting themselves with amazing efficiency.”

Whitaker took note of the Land Army uniform, which became a hot topic of conversation in that summer: “The official uniform has called forth criticism,” she reported. “Farm laborers don’t wear uniforms. But those uniforms are proven to be an essential and desirable asset, for not only are they intensely practical, but they have exactly the same effect on girls as they do on the men—one lives up to a uniform.”

As in the military, the Land Army uniform also served as a great social equalizer and provided a powerful sense of social cohesion. “The cotton uniform,” wrote one California farmerette, “soon muddy and fruit stained, in which some girls looked picturesque, but no one overwhelmingly beautiful, leveled all distinction except those of personality, manners and speech.”

As the season progressed, Idella Purnell was promoted to the captaincy of her own squad of Land Army workers. But amid the grape vines of Lodi, captain Purnell encountered what every American feared in this time of war: the snake in the garden, the saboteur. At first Purnell assumed the woman was simply that lesser form of wartime menace, the slacker, not willing to do her share, but Purnell’s suspicions hardened when her lazy farmerette resorted to shoddy picking: “She took to sabotage,” Purnell explained. “Green grapes, rotten grapes—anything and everything went into her boxes, tossed there by a hand careless of the precious bloom—and they all were only half full.

Purnell tried to handle the situation herself:

I remonstrated—mildly at first. I showed her again…At noon I made a special talk to the girls for her benefit, in which I pointed out that we were soldiers just as much as the ones ‘over there,’ that we too had a chance to make good—or to be classified as slackers and cowards. I made it clear that a slacker was a person who tried to palm off poor boxes of grapes for good ones. One bad bunch ruins a whole box, and that is the same as helping shoot cannonballs at our boys.

But the slacker farmerette did not improve: “In fact, she seemed to take a malicious delight in doing her worst, and trying to get away with it,” said Purnell. “I argued, pleaded, threatened and scolded by turns. Commanding did no good. “That night I made a report to the camp supervisor, and learned that mine was not the first complaint against her. Mine was the last straw, and she was dishonorably discharged.”

A saboteur farmerette in the ranks was exceedingly rare; more often the Land Army worker was hailed as the “Patriot Farmerette.” And in that role, she deserved a “pin-up” above her cot, a photo of a handsome movie star to inspire her, just like her brother in the army or navy had his starlets, teased L A Times reporter Alma Whitaker, who archly exhorted the local movie industry’s matinee idols to do their bit by becoming “godfathers” to farmerettes and other women war workers:

Now, while our masculine regiments are well supplied with fair godmothers, not a single godfather has arisen for the benefit of the land army girls or the war efficiency motor maids or the Red Cross chapter girls… It isn’t fair. What are the stylish picture heroes thinking about? Why isn’t Charlie Chaplin or Douglas Fairbanks offering themselves in this guise? Is masculinity trying to assert, in this day and age, that women’s patriotism is not as important and self-sacrificing as men’s patriotism? Pshaw!

Think of the land army girls, exuding honest sweat on California farms, day in and day out, in uniforms quite as becoming as any at Camp Kearny…all without a godfather.

It would be such a nice compliment if, say, Charlie Chaplin should adopt the first unit of the woman’s land army and go down to see them decked in a land army uniform, just as Mary Pickford wore khaki when she went to San Diego.

There are no known photos of Charlie Chaplin donning a Land Army uniform, but the farmerette was truly a star in California in the summer of 1918.