Fly Along on a Border Patrol

And meet the pilots fighting illegal immigration.

:focal(2217x1440:2218x1441)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f4/8f/f48f6711-8a7f-4e4e-b20f-b17f88a1de9f/03c_aug2017_151210-h-ni589-0329ann_live.jpg)

“Beautiful flying, J.P.” James Pridgen doesn’t acknowledge the compliment paid him by his copilot, Chad Smith. He is preoccupied with tweaking flight controls to suspend the helicopter some 25 feet above the ground and 50 yards north of the Rio Grande in south Texas. Beneath the craft, a scraggly mesquite tree quivers in the downwash.

The baritone whomp-whomp-whomp of the rotor also stirs up dry grass around a man in jeans and a sweatshirt who lies in the underbrush on his belly in a posture of surrender, arms extended in front of him. He has given up his bid to sneak into the country after having an HK .40-caliber assault rifle poked in his direction from one of the Huey’s open doors. A companion has run on.

Pridgen keeps the Huey hovering as a marker for another U.S. Customs and Border Protection agent, who is working his way through entangling scrub trees. When the agent finally kneels to handcuff the man, Pridgen pushes the cyclic control forward, and the chopper drifts ahead over treetops.

Pridgen, 41, is an air interdiction agent with Customs and Border Protection’s Air and Marine Operations in McAllen, Texas. Day after day, he and fellow air interdiction agents swoop down in helicopters to eyeball suspicious tracks and scour underbrush. At night, they use forward-looking infrared (FLIR) cameras to track human movement along the river. Day and night, they fly small Cessna aircraft equipped with surveillance technology over buildings and vehicles of interest.

And, yes, occasionally agents point rifles at people. “Lots of times when they’re shown a gun, the suspects on the ground just laugh and keep running,” Pridgen said after landing the Huey at McAllen Miller International Airport. They know apprehension is left to agents on foot.

McAllen Air and Marine Operations (AMO) doesn’t quantify its work in apprehensions; it counts flight hours. Hours jumped from 5,600 in fiscal year 2014 to 9,200 in the following 12 months as border crossings surged, including those by families and unaccompanied children from Central America. The influx is heaviest in south Texas, where AMO air crews look down on 315 miles of the Texas-Mexico border and 117 miles of the Gulf of Mexico coastline, as well as checkpoints in contiguous areas.

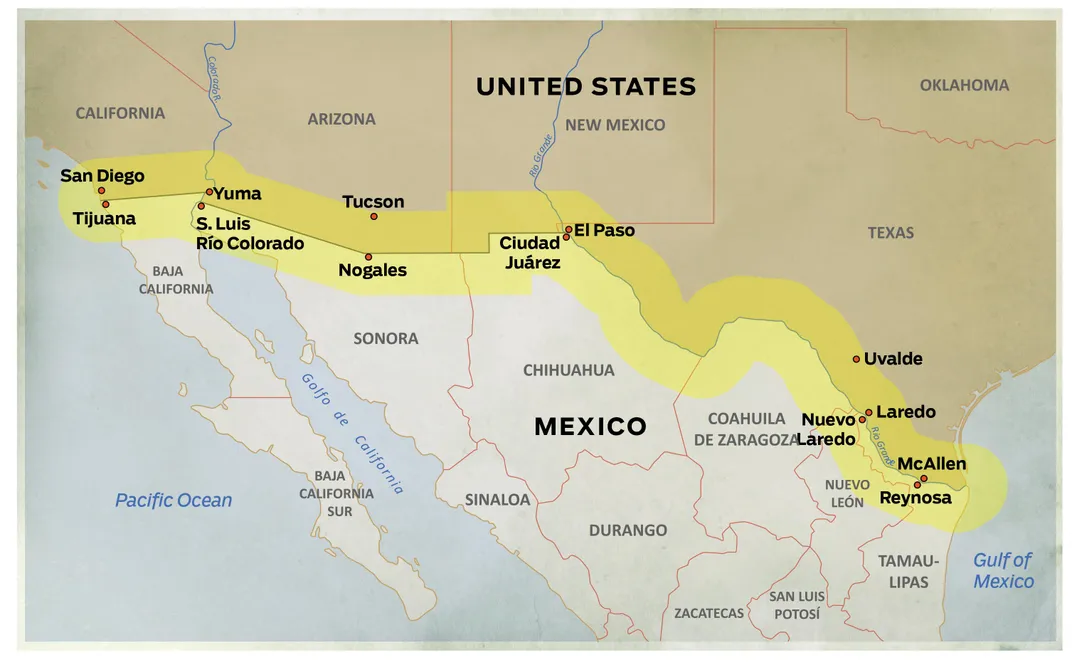

Thirty years ago, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the hot spot was San Diego. By a decade later, the flood of illegal immigration had shifted east to Yuma, Arizona, and then to Tucson. When I visited McAllen last October, agents there had spotted a total of 138 people heading north from the Rio Grande. The same day, agents in Tucson recorded just 19 sightings. “Tucson beats us in dope,” Pridgen said. “We win in bodies.”

Because they only see border-crossers, rather than interact with them, air interdiction officers talk in impersonal terms, as in “I see bodies!” and “We have lost so many bodies in these sugar cane fields.” They never speak to the people they spot, let alone cuff them. The intruders are distant objects that run and scurry under bushes, and the agents classify them by outcomes. For one two-hour flight in October, the totals were: four gotaways, six apprehensions, four turnbacks (back across the river), and one negative (a dead body).

Some intruders are higher value than others; drug traffickers and other criminals are the primary targets. But a great many border-crossers are family groups with children, and their numbers doubled again in fiscal year 2016 from a year earlier, according to Border Patrol data. When AMO helicopter crews encounter such groups, pilots see upturned faces but little other reaction from the walkers, who just keep walking. “We’re not really interested in those people,” says William Durham, the director of air operations at McAllen, though, of course, Border Patrol agents on the ground intercept them.

**********

After we take off from McAllen, Pridgen, Smith, and I look down on agrarian countryside on both sides of the lower Rio Grande, a semi-arid range of irrigated fields, sprawling ranches, and red-grapefruit orchards. On the Mexican side of the river, a John Deere tractor neatly disks rich alluvial soil in long straight passes. A hundred yards north, on the Texas side, is a tangle of untended live oak, mesquite, and prickly pear shrubs methodically explored by Border Patrol agents. Five miles up the river, the Texas side may have the farm and the Mexican, scrub.

The lower valley, besides being the closest entry point into the United States for Central American refugees, has less daunting geography than most of the 2,000-mile southern border. Farther north, in Big Bend country, the river runs through canyons and steep escarpments. Then the border cuts west from El Paso across the barren Chihauhaun and Sonoran deserts to the Pacific Ocean. Besides McAllen, six other AMO stations dot the border from the gulf to the ocean. Uvalde, Laredo, and El Paso, Texas; Yuma and Tucson, Arizona; and San Diego, California.

In the desert stretches, towns are too sparse for an intruder to easily disappear into a resident population. Whereas in south Texas, population is more numerous and swells further in the winter when RVs from the north congregate under a warm sun. Drug carriers prefer the isolation of the desert, but people carrying nothing just want to hide. In the lower Rio Grande Valley, there are more runners than carriers.

AMO is a police force—the world’s largest civilian air and marine law enforcement organization, employing 1,800 people. Its agents, federal law enforcement officers, experience some of the same exasperation U.S. law enforcers of every stripe face when criminal apprehensions far outnumber successful prosecutions. Agent and pilot Tobin Viehland says he loves his job but admits to frustration that it’s “never done.” “It is more like a game, really, rather than a war where you hope to win,” he says. “Each day we each contribute as much as we can to doing the job.”

Pridgen has developed an attitude that helps him cope. “If I feel I have done the best I can for a day, what happens afterward doesn’t matter,” he says. “There is nothing else you can do.”

“That’s law enforcement,” says William Durham. “Law enforcement in this country, because of our civil rights, is reactive.” More proactive border enforcement policies, such as automatic deportations, might discourage border incursions, but such nostrums fall squarely in the political arena, a place Durham does not enter. “I absolutely try to stay out of that,” he says.

What concerned him in October is that he had only two-thirds of the pilots he needs: 18 on staff, nine slots open. He blames the personnel shortfall on a tight market and a “long and laborious” federal hiring process. This includes passing a background security check and polygraph test, having a first-class medical certification to fly, completing flight evaluation oral and written exams, and having 1,500 hours of flight time. If you want to become a law enforcement officer, there are obviously easier ways. On average, just three of 100 AMO applicants qualify.

Until last October, the bar was even higher: AMO advertised exclusively for dual-rated pilots: helicopter and fixed-wing. But because many helicopter pilots lack fixed-wing time, the pool of candidates was shallow, so the requirement was lowered by the recruiting command tasked with addressing the shortfall. Agency officials in Washington say AMO units overall have 12 percent fewer pilots than needed.

Beyond flying skills, Durham says, applicants must demonstrate good character, as determined by psychological testing. “Without integrity, it is impossible to do this job. They have to be willing to go to a neighbor and say, ‘Hey, you’re breaking the law and we have to do something about it.’ ”

McAllen neighbors may well be open to sheltering undocumented immigrants. What’s more, the neighbors could be family. “Some of the folks [pilots] out there, their parents came over as immigrants from Mexico,” says Durham, a native of Corpus Christi. This is, after all, an area of the United States where some families can claim they have been here since before Mexico’s Santa Anna surrendered to Texas rebels in 1836.

**********

“Welcome to my office.” Agent Victor Garcia is squeezed in one of two back seats of a Cessna 206, his knees bumping an electronic monitor. A second swiveling screen is to his left. With both hands, Garcia grips a device resembling an Xbox controller.

In the left front seat, agent Ryan Smith pilots the 300-horsepower, high-wing aircraft. On an iPad mounted to his right, Smith can see what Garcia is pulling up on his screen. Smith generally steers the craft to the right of targeted objects so the left side-mounted FLIR camera doesn’t peer through engine exhaust. Smith’s course is considerably north of the river but roughly parallel to it. In the distance, he sees Border Patrol vehicles congregating. Garcia zooms in. Soon his screen fills with images of ducks gliding above shimmering water and, of more interest, an inflatable raft retreating southward. After the craft touches the river bank, six people step back onto Mexican soil and disappear into brush: four men and two women, one wearing a light-colored jacket. These details are clear to Garcia from—without revealing any operational capabilities—a long ways away. Border-crossers seldom see the small plane.

“We fly at night 95 percent of the time,” says Smith. “When we’re not worried about being seen, we’ll fly at 5,500 feet. If we don’t want to be seen, we’re closer to 12,000 feet.” The Cessna can patrol for seven hours, twice the flight time of choppers.

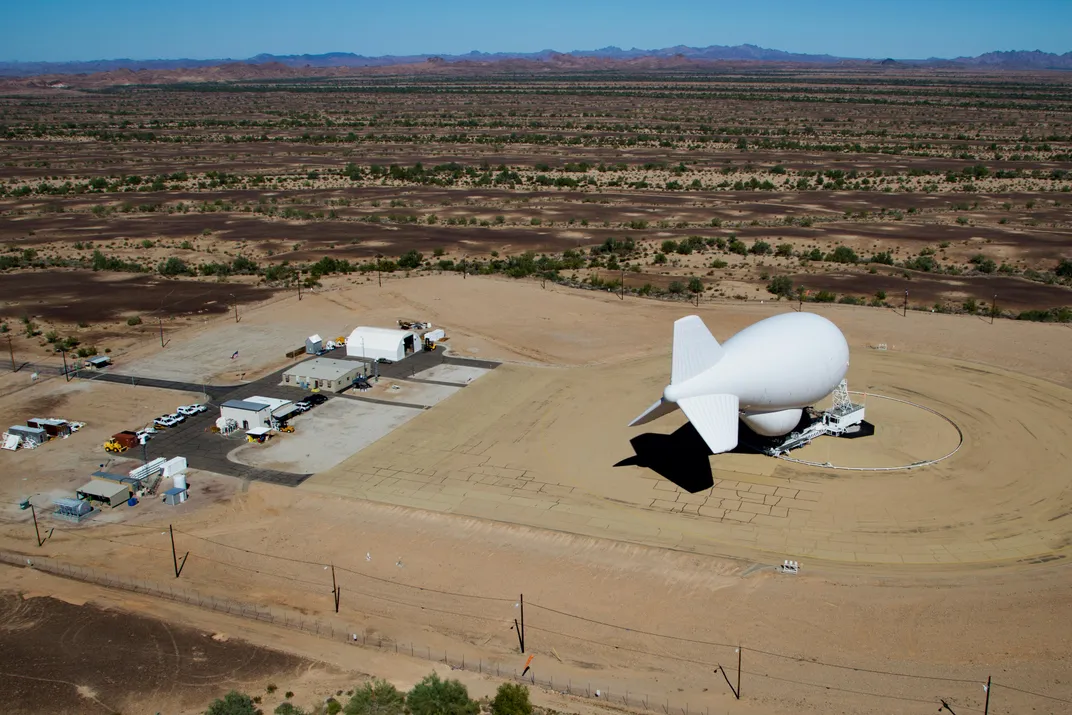

Radar system images are analyzed on board and, as needed, transmitted to monitors on the ground or recorded as evidence. The latter is helpful when the radar captures fleeing drug traffickers dumping narcotics. That most often occurs in the Gulf of Mexico when piloted and drone AMO aircraft intercept drug-runners approaching the Texas coast.

**********

The day at McAllen starts at 6 a.m., when agents in tan uniforms and caps, and with holstered handguns, sit in front of a video screen to listen to overnight reports and receive assignments—very general instructions, like “Head northwest”—from the officer of the day, or from Pridgen, a supervisory agent. Pridgen is a former commander of a medevac unit in Afghanistan, so he regularly schedules himself in the right seat of a Huey.

Each of the 14 pilots entering the room first walked from table to table, shaking hands with and greeting everyone who preceded him. Even late arrivals made the rounds.

Before 6:30, agents disperse. “I don’t have a destination when I take off,” says Tobin Viehland. “No flight plan. I have GPS but I mostly fly by landmarks. This is a little different environment than other types of helicopter work.” Viehland has experience in a number of other environments: He’s flown for an air ambulance service, a TV news station, an oil company drilling in Gulf waters, and an air-tour company. After laser surgery corrected his eyesight, he passed Army standards and took a leave of absence to pilot rotorcraft in Afghanistan for the Reserve. About 60 percent of AMO pilots are ex-military.

Viehland is inspecting an Airbus AS350 helicopter, or AStar. His preflight examination is scrupulous: He clambers atop the craft to examine the base of the main rotor, opens compartment doors, shines his flashlight along the helicopter’s thermoplastic body panels. “The AStar has some maintenance and reliability issues,” he says. (Sure enough, at flight’s end, he requested that ground personnel fix a failed hydraulic system serving the tail rotor.) Viehland calls the AStar a satisfactory “all-around” helicopter for covert patrol work, though he personally prefers the pinpoint landing control, reliability, and agility of the aluminum-alloy Hughes OH-6 helicopter, which the AStar supplanted.

Besides the Hueys and AStars, pilots at McAllen fly Cessna single-engine aircraft that date from the 1960s. Durham has reservations about the lineup. “We need military-grade in this job,” he says. “We treat our aircraft as military units, but we have business-grade. We beat them up.” He cites the AStar’s composite blades. “If we nick a cactus or a piece of grass, that means a $30,000 tail rotor replacement. If we stir up a pebble that hits a main rotor blade and puts a pinhole in it, that’s a $100,000 rotor system.”

From other AMO bases, the Customs and Border Protection flying service employs a varied fleet, including Airbus EC120 and Sikorsky S-76 and Black Hawk UH-60 helicopters. Some agents fly Cessna Citation twin-jets, Beechcraft Super King Air twin-engine propeller craft, and the Lockheed P-3 Orion. In Corpus Christi, pilots operate the General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper uncrewed aerial vehicle.

“We are a high-capital operation,” Durham says of the fueling and maintenance costs the menagerie of aircraft incur. With an annual budget of $800 million, keeping the fleet current is difficult: “It takes 10 years to replace a plane at the end of a life cycle. That’s difficult to do on a budget cycle of one or two years.”

McAllen pilots pull four-hour shifts and typically fly twice during each shift. At peak activity, the shifts may run twice that long. The AMO aircraft used to fly 24 hours a day, but experience—and, possibly, budgetary considerations—pared that schedule. Flight scheduling now is both routine and creative, blending the need to be in the air at the busiest times of the day and night with guesses about when cartel scouts expect the aircraft to be airborne. “Drug cartels have a lot of assets and know where we go and what we do,” Viehland says. “They do a lot of trafficking through here and succeed at it. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t keep doing it.”

**********

After radar operator Richard Russell meticulously cleans the lens on a front-mounted FLIR camera, the AStar is towed out of the hangar on its rolling, 14-foot-square landing pad, and the three-blade rotor quietly lifts the AStar into the dawning sky. FLIR is particularly effective when the ground is cool and body heat signatures stand out in contrast.

Viehland flies northwest from McAllen, and five minutes into the flight he spots a trio of Border Patrol vehicles around a farm field. “If you want some high-low surveillance, we’re up to it,” he radios an officer on the ground, who accepts the offer. After slowly circling the field, Viehland drops lower and slides the AStar sideways above rows of thickly planted, 10-foot-tall sugar cane. The plants flutter and wobble and Viehland conscientiously stays high enough to prevent rotorwash from breaking the stalks. No “bodies” are spotted.

Seeing a string of footprints heading across a plowed area near the cane field, Viehland says: “They came across here and went into that grove.” A brushy field edges the grove. “Last time that’s where the bodies were, in the brush, but last time doesn’t really mean much this time.”

After a fruitless 10 minutes of crisscrossing the sugar cane, Viehland says, “I guess we’ll go find something else.”

As the AStar flies farther northwest, the winding Rio Grande is visible out the left window, ambling southeast like a supple snake. A pair of Border Patrol river boats are racing upstream, but their passage is laughably slow: The craft sometimes travel a mile to progress a few hundred feet. The stream’s meandering is so severe that one can stand on appendages of Mexican soil poking north and look southward into the United States.

Most of the encounters between border crossers and agents occur between the bank of the river and the first road to the north. The road sometimes runs on top of a levee wall, which has several incongruous open gateways so property owners can reach river-hugging fields. The levee is a landmark for pilots. Field irrigation wells also guide the air crews, such as Taylor’s Pump, on the edge of a windrowed hayfield circled on this flight.

Week after week, pilots are lured back to the same tilled fields and unimproved acreages with beaten-down paths left by runners. Obscured by tall grasses, runners can sometimes lie unseen by agents who walk right by them—but they are rarely missed by pilots. Aircraft clearly have the advantage along the Rio Grande. That salient truth is universally understood—by pilots, border agents on the ground, and especially the people who run from the helicopters and, under cover of low-lying, entangled branches of shrubby trees, try to disappear.