Meet the Howards

A family of comfortable pleasurecraft, descended from a raceplane.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/73/45738874-5ab4-4344-b2f2-8e9beec03dd8/04l_on2015_b34p1782_live.jpg)

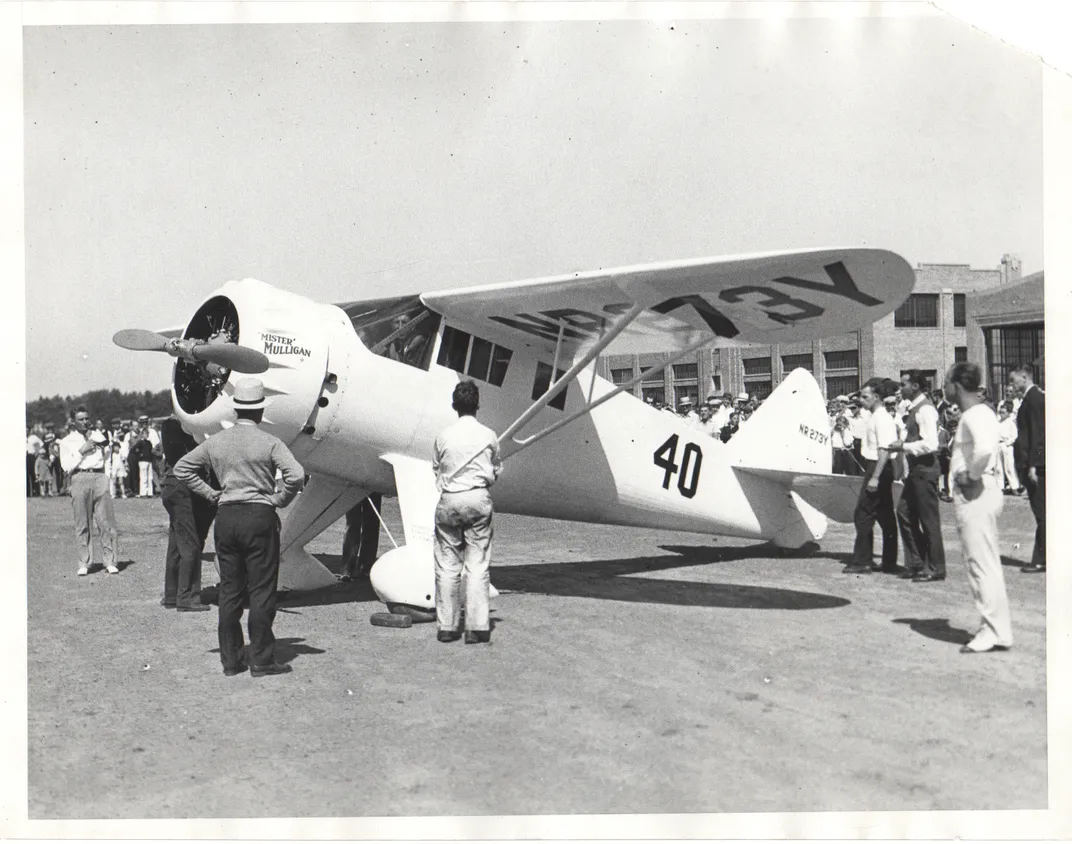

Happy hour at the Siren airport in far northwest Wisconsin. On the ramp, sitting beneath the high wings of half a dozen 1940s Howard airplanes, a growing, graying, and security-badge-less gang is imbibing. It’s an homage of sorts. Long before he gained fame building racers in the 1930s, including the revered Mr. Mulligan, Benny Howard got his start in the airplane business by modifying a World War I biplane trainer to carry extra cases of hooch for Prohibition-era bootleggers. One very impressed customer dubbed it a “damned good airplane,” and from then on, Howard used the designation “DGA” for all his designs.

The assembled tipplers are DGA disciples. As the sun sets, more of the vintage tail draggers arrive, bounce down the runway, and park. Hearty greetings are extended, and it’s bottoms up.

This is the first day of the Howard Aircraft Foundation’s 2014 summer fly-in. The gathering is an annual event traditionally held in late July on the weekend before the Experimental Aircraft Association’s massive yearly conclave in Oshkosh, about an hour’s flight to the southeast. Howards from across the country have been gathering here for more than two decades, thanks to the largesse of Howard enthusiast Al Lund, 84, who lives not far away on Stone Lake, outside Hayward. Lund owns two flyable Howards, and his hangar at the Hayward airport is stuffed with enough fuselages, wings, engines, and assorted parts to build a half-dozen more. In a couple of days, foundation members will hop in their airplanes and fly over to Hayward, get shuttled out to Al’s house for lunch, and then ride back to Hayward airport for an enormous pig roast dinner he throws once a year for everyone even tangentially associated with Howards or his home field.

Tonight on the ramp at Siren’s Burnett County Airport, most of the airplanes are Howard DGA-15s. Howard Aircraft manufactured a lot of them—520—between 1940 and 1944. Almost all were built for the U.S. Navy, which flew them as officer transports, instrument trainers, and air ambulances; after World War II, they were sold as surplus to the civilian market. The contract wasn’t profitable for Howard Aircraft; after the war, the suburban Chicago company was liquidated and the proceeds reinvested in an electric motor plant in Racine, Wisconsin. Benny Howard left the company he founded to join Douglas Aircraft as a test pilot. When he died in 1970, Donald Douglas Sr. wrote, “There probably never was, nor will there ever be, another human being as interesting as Benny, as intelligent, as exasperating, or as lovable.”

Ben Odell Howard was one of those “grease-stained entrepreneurs,” in the words of Time reporter Paul O’Neil, who learned by doing during the golden age of aviation in the United States—an era of races and records between Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 Atlantic crossing and the early 1940s, when airplane makers’ shops sprouted in small towns and air exhibitions drew crowds 50,000 strong. Almost all of the golden age entrepreneurs, wrote O’Neil, “had absorbed what they knew of aeronautical science by tinkering with Jennies and Standards as barnstormers and by building, and risking their necks in, later models of their own.” Instead of enrolling in flight school, Howard read a book on how to fly, then bought a second-hand Standard biplane and quickly crashed it. (His passenger died in the crash.) When Howard got out of the hospital, he “made a deal,” as he put it, with a flight instructor. He later raced Roscoe Turner and Walter Beech and beat them both.

Today, some 200 Howard airplanes remain on the Federal Aviation Administration’s registry, but only a few dozen are flying. Of those, most have undergone extensive restoration. Rebuilding just a set of wings for a DGA-15—wooden frame, mahogany plywood, and fabric—can be an eight-month, $100,000 adventure; overhauling the big, nine-cylinder, 450-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-985 Wasp Junior engine can tack on up to another $50,000; add to this updating the electrical system, rewelding and recovering the metal-tube fuselage, new paint and interior, and a few modern conveniences such as an electric fuel pump and new radios, and the total can soar to $250,000—or a lot more.

“You’d be counting your blessings if you were just a quarter-million into it,” says Jim Kreutzfeld of Castle Rock, Colorado. Kreutzfeld has had a hand in several Howard restorations and owns a 1940 DGA-15P. So does his brother Ken, an internationally known Howard specialist who owns K & M Restorations in Marblehead, Ohio.

Working with designer Gordon Israel, Howard specialized in very-limited-production racing aircraft, the most famous being the DGA-6 also known as Mr. Mulligan, winner in 1935 of both the Bendix distance race and the Thompson trophy for closed-course racing. In 1936, Howard crashed the airplane near Crownpoint, New Mexico, during his last stretch in the Bendix New York-to-Los Angeles race, seriously injuring himself and his wife Maxine, known as Mike. As a result of the crash, Howard lost a leg. Most of the Howard Foundation members who showed up in Siren learned about Mr. Mulligan after they became interested in Howards, as opposed to being drawn to the brand because of the racer. As colorful as Benny Howard’s history is, his airplane still sells because it’s a damned good airplane.

In 1970, parts from the original Mulligan were salvaged from the crash site and used as patterns to build three replicas, each a little different from the others. The first crashed in 1977 during a speed run over Tonopah, Nevada, killing builder Bob Reichardt. A second replica was built by Jim Younkin of Springdale, Arkansas, in 1985. (Younkin, who invented a solid-state autogyro system, got his first airplane ride in a Ford Trimotor in 1934 and is the father of the late Bobby Younkin, an airshow legend. He was a kid when Howard crashed the original.) His replica, powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1340, took more than 8,000 hours to build and is displayed at the Arkansas Air Museum. Younkin also collaborated with a friend, the late Bud Dake of Creve Coeur airport near St. Louis, to build three Mullicoupes, loosely based on Mr. Mulligan but with the smaller R-985 engine and a modern steel-tube fuselage. In 2009 Howard enthusiast Bruce Dickenson of Santa Paula Airport in California built a hybrid of a DGA-6 and a DGA-15 that he called the DGA-21. Howards seem to attract what might be called a second generation of “grease-stained entrepreneurs,” a gang of DIYers who stayed true to aviation after the world moved on.

Howard used Mr. Mulligan as the template for a series of aircraft designed for the general public. The four-seat DGA-8 that emerged in 1936 was the first in a family that used the same fuselage but different engines. Howard sold 18 DGA-8s, powered by the Wright R-760; seven DGA-9s with the Jacobs L-5; four DGA-11s with the Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior; and two DGA-12s with the Jacobs L-6. Between 1936 and 1939, the company built a total of just 31 in the series.

The DGA-15 was a different story. Launched in 1940 and designed to compete with the cabin-class single-engine business aircraft of the day—airplanes like Beechcraft’s B-17 Staggerwing and the Stinson V77 Reliant—the aircraft sold well until the U.S. entry into World War II, when the factory began producing military variants. Howard’s brochure for the Model 15 boasted of a rear seat with “motor car comfort for three” and a cabin with “scientific soundproofing” and “only the finest broad-cloth and leather.”

Frank Rezich, 92, remembers building the airplanes that had to live up to those promises. At 17, he was the assistant to the factory superintendent. In 1940 Howard was a shoestring operation, with only 50 employees, individually making aircraft to order for high-profile customers like Jimmy Doolittle and actor Wallace Beery. “There was no assembly line, we did not build on a production basis,” says Rezich. “Customers would send a deposit and we would start building an airplane.” Rezich remembers Howard as “intense, demanding, and a perfectionist.” Before releasing an aircraft for first flight, Rezich says, Howard would examine the smoothness of the finish; he’d run his hand over the fuselage, then “put his handkerchief on top of the fuselage and see if it would slide down.”

**********

“It’s the best ride out there,” says Dennis Lyons, a former American Airlines pilot who prefers the Howard to the Beech Bonanza he owned earlier. “It’s not as fast as the Bonanza and it’s more challenging to land, but it rides turbulence better.” Lyons and his wife Susan have owned their blue DGA-15P, named Archibald B, for 10 years. Lyons says he can fly it from the airport near their home in San Miguel, California, to Chicago with just one stop for gas.

“You know this airplane doesn’t know whether it’s 1945 or 1995 or 2015,” says Lyons. “Flying across Wyoming, nothing down there, you get the same feeling as the guy who first flew it.”

“I’m not interested in going anywhere fast,” says Mike Merritt, of Kennesaw, Georgia, owner of a 1944 DGA-15P, who retired after spending 20 years in the Air Force and later working as a civilian test pilot for Lockheed Martin. He’s flown the F-117 stealth fighter and the F-22/A Raptor, but today he’s happy to poke along in his Howard at 130 knots—about 150 mph. For its time, Merritt points out, the DGA-15 was pretty fast, with a top speed of 175 knots. “And expensive—more than $17,000,” he says. “But it is very solid. It has a great useful load—you can really put in four people and their luggage and go places. Range with full fuel is almost 1,000 miles.”

The -15 has plenty of idiosyncrasies, and landing it is not easy, even for pilots with lots of tailwheel experience. The main gear carriage is fairly narrow, and if you hit it hard there is no give. If you don’t nail your landing speed just right, you’re going to bounce—rapidly. The only way to recover is to go around or move your feet on the rudder pedals faster than a ballerina on hot coals. The best way to land a Howard is to pitch up into a perfect three-point landing—much easier said than done.

One reason Howards are so stable, particularly in turbulence, is that there is no fuel in the wings to create an imbalance. The gas is stored in a series of three belly tanks that collectively can hold up to 151 gallons. The tanks have to be filled individually, and gassing a dry Howard can take up to 30 minutes. “A curved filler tube is used to get to the top of each tank,” Merritt says. “You have to pump in the fuel slowly or it will spit it right back out at you.” Unless the aircraft has been modified with a modern electric fuel pump, on startup you pump fuel to the engine with a mechanical “wobble pump.” Merritt recommends landing and taking off with the selector switched to the forward tank, the one closest to the engine.

On an overcast morning, Merritt takes me along for a ride. You enter the aircraft through a right-hand cabin door between the sumptuous rear bench seat and the front pilot buckets and navigate up the incline. On the instrument panel, one switch is marked “flare dispenser,” signaling the era during which the airplane first flew. Howards could be fitted with an aft flare dispenser, which illuminated the ground below for night landings on unlighted grass strips. It also started more than just a few fires. Says Merritt: “Pyrotechnics and airplanes generally don’t mix.”

For a single-engine tail dragger of this vintage, the Howard is a heavy beast—4,350 pounds—and speeds are higher all around—takeoff, stall, cruise, and approach—than those of many of its contemporaries. Taxiing side to side for visibility requires deft throttle application, as the Howard’s relatively small rudder needs a fair amount of blow over the surface to maintain directional control on the ground.

Peripheral vision is the lead sense required on takeoff; that is, until the tail wheel comes up at 50 mph and you get your first glimpse of one of the features that makes this airplane special: that amazing panorama out the windscreen. At 70 mph, you’re airborne, climbing at 1,800 feet per minute. Then you feel a second feature, that amazing stability: Take your hands off the yoke and it just stays put.

Merritt and I head north from Siren to Lake Superior’s Apostle Islands, weaving between the bluffs and beaches, banking around the restored lighthouses, and enjoying the views from the elegance in the air.

**********

Howard owners all have stories about how they found their airplanes and the multi-year sagas of rebuilding and restoration that followed. In 2001, current Howard Foundation president Presley Melton, a courtly, retired casket wholesaler from North Little Rock, Arkansas, found his 1943 DGA-15P in pieces in Washington state. He didn’t know much about Howards; he just knew he wanted something with a 450-hp Pratt & Whitney R-985 engine. After the war, the airplane had been used by the tony Greenbrier hotel in West Virginia to shuttle guests, then had a succession of owners from Alaska to North Dakota. When Melton got it, it hadn’t flown since 1975. He had it trucked back to Arkansas. The showpiece restoration took until 2010, and Melton freely admits he exceeded his budget, but his airplane did win the 2010 EAA award for Antique Reserve Grand Champion.

Craig Bair first saw a Howard when he was eight and visiting the Denton, Texas airport, near Dallas. “I thought: That is the coolest airplane ever,” he says today. About 40 years later, he feels the same way. He bought his first Howard, a DGA-15P, in 1997.

When his father died in 2000, Bair sold the -15 to raise the money needed to buy his dad’s old Cessna 195. “As a kid, I grew up in that airplane,” Bair explains, and the thought of the 195 going to someone else was unthinkable. But, he says, “After I bought the 195, I missed the Howard—bad.”

Bair puts his admiration in automotive terms: The Cessna 195 is like a family sedan; a Howard, that’s a limousine. He found his second Howard two years ago in North Dakota. Although he once ran an aircraft restoration business and is a licensed aircraft mechanic, his day job kept him too busy to restore the second Howard himself. He took it to Howard specialist Rick Atkins of Ragtime Aero in Placerville, California. Two years and $400,000 later, Bair is the proud owner of what could be the finest ground-up restoration of a DGA-15P ever. Bair and Atkins consulted old Howard brochures and documents to make the final product look like the original, right down to the patterns on the map pockets. While everyone else’s airplane sat out overnight, Bair tucked his into a hangar. You really can’t blame him.

Dennis Lyons was at Santa Paula Airport one day when he saw a Stearman biplane with a big Pratt & Whitney engine take off, then, not long after, return. “One of the cylinders on the engine was missing, gone, not on the engine anymore,” recalls Lyons. The pilot had flown almost 15 miles back to the airport with a cylinder missing. Lyons remembers thinking, “I want to fly behind an engine like that.” A friend of Bruce Dickenson, Lyons knew about Howards and the big Pratt & Whitney that powered them, and a short time later he bought one.

Alex Vickroy wanted a Howard before he could drive. In 2006, when he was 18, he saw an ad for one on floats in Trade-A-Plane. Alex lives in Wisconsin; the airplane was in Alaska. He tore out the ad and kept it—for six years—before calling the owner, who still had the airplane. By 2012, Vickroy was a commuter airline pilot and had saved a little money. He went to Alaska, bought the airplane, and flew it home. It still looks very much like the working airplane it was in Alaska for more than three decades after receiving the Jobmaster cargo conversion and being mounted to a pair of enormous Edo 6470 aluminum floats. Vickroy likes to fly it to his fishing cabin on Lake Superior in Ontario, 40 miles from anything and accessible only by boat…or floatplane.

When it comes time to visit Al Lund, Vickroy taxis into Lund’s lagoon and parks next to his float-equipped de Havilland Beaver. Everyone else catches a ride from the airport.

The lunch with Al is bittersweet. He’s dying and everyone knows it. In less than five months he will be gone. He’s mentored just about everyone in the Howard Foundation, and they have come to share a few laughs and say goodbye. Lund made his fortune in a series of businesses, but in his study there is no trace of any of them. He is surrounded by memorabilia and photographs of a life in aviation and of family. The two have been intertwined as long as his children can remember. Several of them are pilots and they can’t discuss their father without talking about airplanes. (At this year’s gathering, Al’s wife Lois opened the hangar to the club, and the family once again hosted the lunch and dinner.)

Al tells me that his Howard parts stash is for the benefit of the foundation’s members and he doesn’t want anyone making money from it. He was one of serveral who pooled money and effort to acquire the Howard DGA-15 type certificate in 2003, assuring that parts would be available to keep the Howards flying.

We go outside on the deck overlooking the lake where everyone has gathered. It is a flawless summer afternoon—brilliant sunlight, a few scattered clouds, and a light breeze. Painfully short, summer in northern Wisconsin doesn’t get any better than this. Al sits down. The radials from the lagoon fire up. Al’s son Jim taxis out in the Beaver. Vickroy pulls up alongside him in the Howard. Throttles advance and the race is on. Vickroy lifts a float first. Al Lund leans back in his chair. There is a glisten in his eye and he is smiling. For the DGA disciples, it is a Damned Good Afternoon.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/2f/242f8b31-5300-4d36-bfec-69b8b00f6f09/04x_on2015_benmike_live-web-resize.jpg)