The Voyages of John Glenn

Two trips to space, 36 years apart.

:focal(530x362:531x363)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/f5/2bf547da-2954-45c5-8be5-ab6dfb988730/1998_glenn_walkout.jpg)

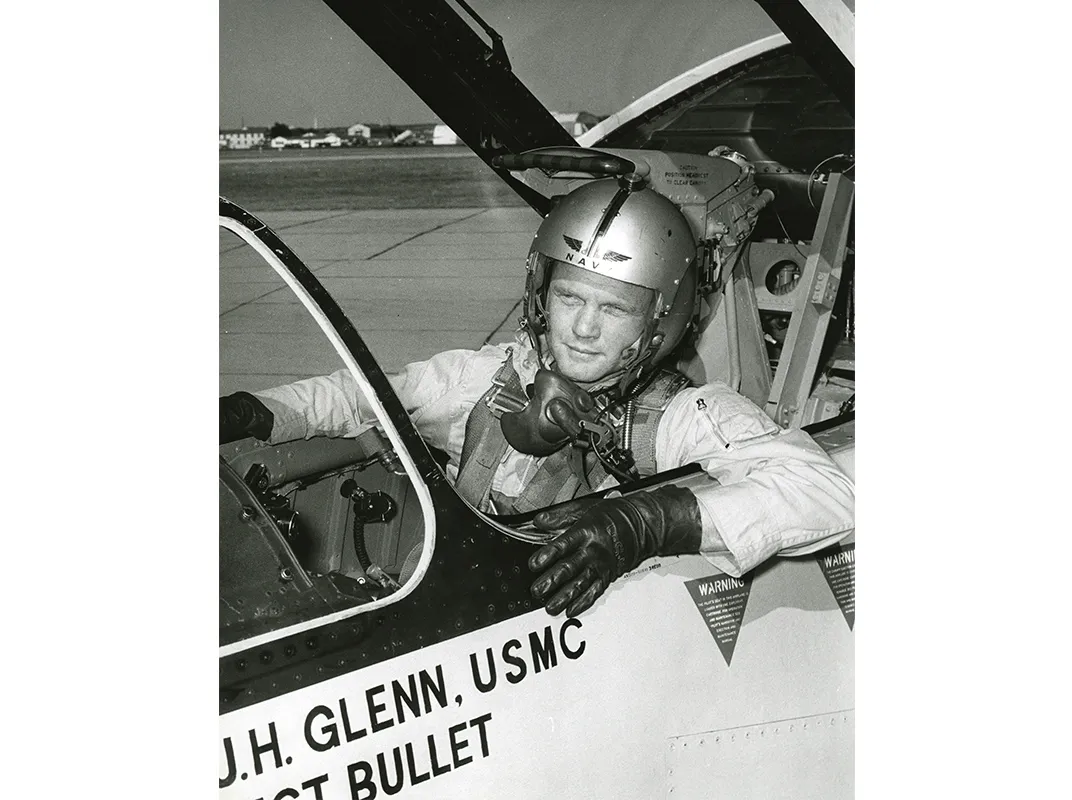

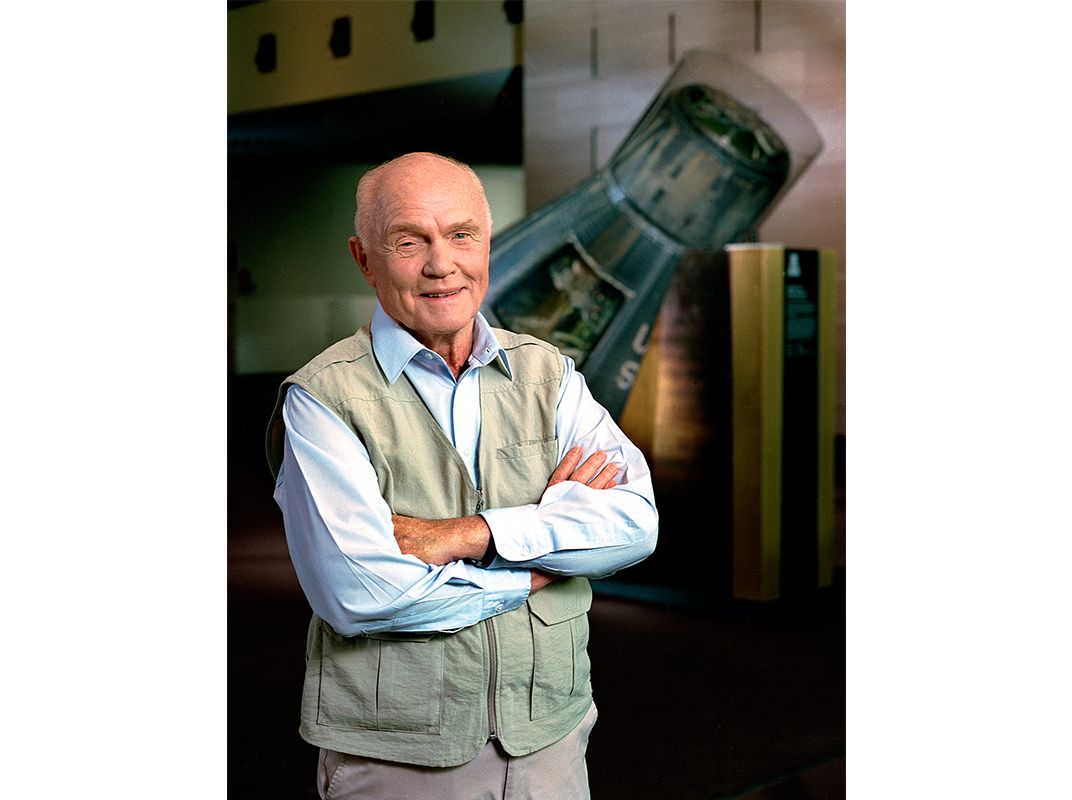

The first American to orbit Earth was the last of the Mercury 7 to leave us; John Glenn died last December 8. In his 95 years, Glenn was many things—war hero, test pilot, Senator, devoted family man. But to the public he will always be the quintessential astronaut. And he earned that stature—as well as lasting fame and world admiration—based on only two spaceflights.

Shortly after 8 a.m. on February 20, 1962, technicians at Cape Canaveral, Florida, closed the side hatch of John Glenn’s Friendship 7, sealing the 40-year-old Marine pilot into his tiny, one-man spacecraft. After a series of schedule slips that winter, this would be NASA’s second attempt in less than a month to launch the first American into orbit. From this point on, Glenn’s only contact with the outside world was through the headphones in his helmet. Fellow Mercury astronaut Scott Carpenter, connected by a landline from the Atlas rocket launch center 750 feet away, kept him informed on the progress of the countdown. During a break in the preflight checks, Carpenter took advantage of the lull to patch in a phone call to Glenn’s family in Arlington, Virginia, on a private channel. John’s wife Annie came on the line, sounding rock-solid. Glenn told her what was happening inside the capsule, and about the blue Florida sky he could see out his window. Before they said goodbye, Glenn reached back across the years to a ritual they had repeated each time he had gone off to war: “I’m just going down to the corner store to get a pack of gum.”

“Don’t be long,” Annie replied on cue, holding back tears.

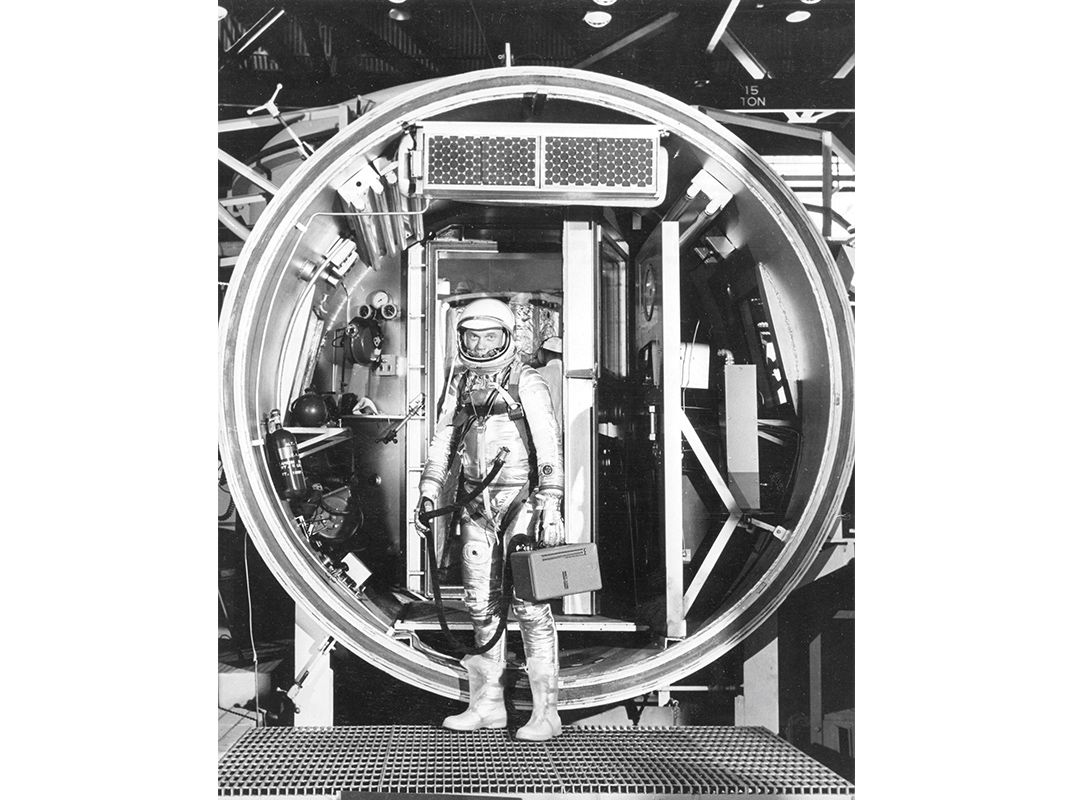

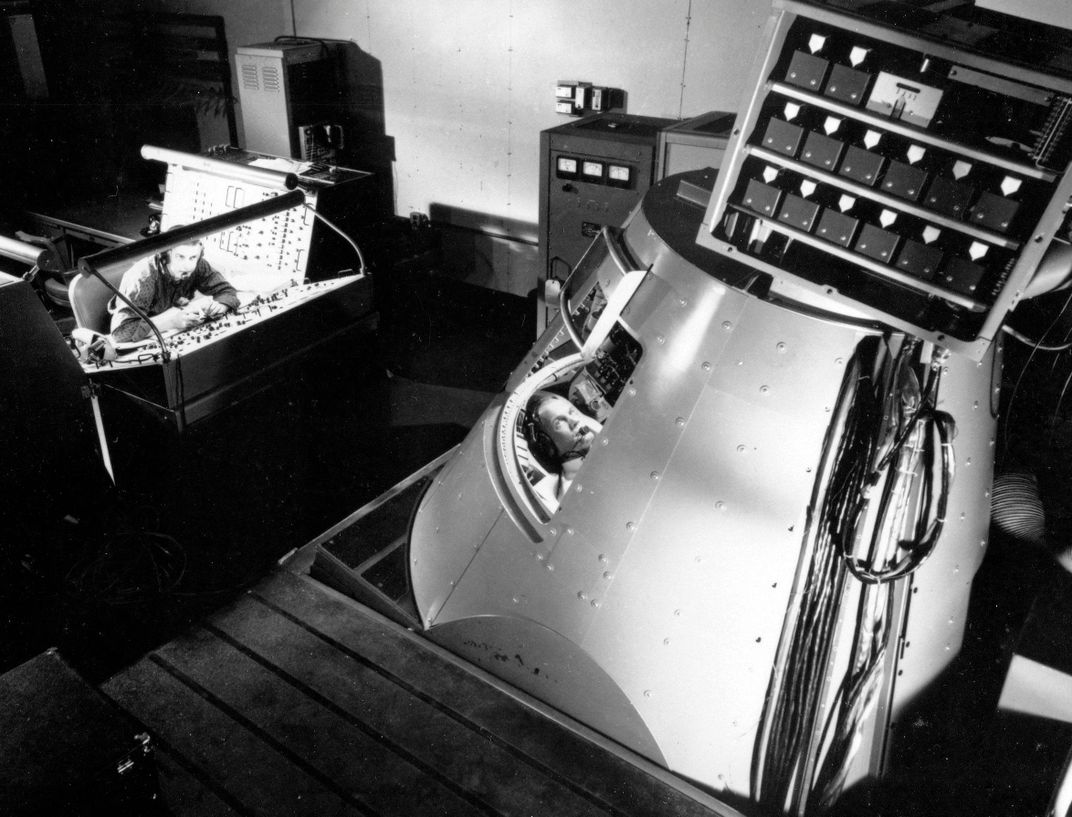

At 9:43, with the landline now disconnected, Glenn listened as Alan Shepard in Mercury Control counted down the final seconds. What he couldn’t hear was Carpenter’s send-off: “Godspeed, John Glenn.” At zero, Glenn felt the Atlas’ engines come to life, and a faint roar penetrated the capsule. Three more seconds passed as they built up to full thrust, then hold-down clamps at the base of the rocket released and he started to rise. “We’re under way,” he announced, his voice vibrating with the engines’ power. Carpenter had told him that after going in circles in the centrifuge all those times during training, it would feel good to be accelerating in a straight line. He was right.

Now the Atlas was arcing over the Atlantic, following the curve of Earth. Glenn kept up a steady stream of reports on his instruments to Shepard; everything was working perfectly. The Gs built to nearly 7, then, with a change less dramatic than he’d expected, fell to 1.5 as the booster engines were jettisoned, right on schedule. The sky turned black as the remaining engine continued to speed him toward orbit, the G-forces building once again to nearly eight times normal. At last, five minutes after liftoff, 100 miles above Earth, the sustainer engine cut off and Glenn felt the onset of zero-G. Under the control of the automatic sequencer, the capsule separated from the Atlas and turned 180 degrees to its proper attitude, blunt end first, for the flight. He was in orbit, the first American to get there.

Friendship 7 was flying with its nose pitched 34 degrees below the horizon, so that outside the capsule’s trapezoidal window, Earth appeared to be receding. After all the worries about the possible debilitating effects of zero-G, Glenn felt adapted within seconds of reaching orbit. Not only was weightlessness no problem; it was pleasant. He passed over the dayside of Earth with amazing speed; as he overflew the Indian Ocean, the sun descended into his view, a white ball as bright as an arc lamp. It reached the western horizon and slipped beneath it, spawning brilliant rainbow bands of color that stretched across his field of view. Glenn had always been what he called a collector of sunsets; he remembered them, he said, the way someone else might recall works of art. Now, as Friendship 7 raced into its first orbital night, he added to his collection the most out-of-this-world sunset any American had ever seen.

“This is Friendship 7,” he radioed to the ground. “I’ll try to describe what I’m in here. I am in a big mass of some very small particles that are brilliantly lit up like they’re luminescent. I never saw anything like it.”

As Glenn talked to the controller on Canton Island in the South Pacific his voice was filled with surprise and curiosity. He’d been watching his first orbital sunrise through a periscope, and after the sun came up he glanced overhead through the capsule’s window and saw thousands of glowing points of yellow-green light.

For a moment he thought they were stars, but then he realized these lights were swirling slowly around the outside of the capsule. They looked just like fireflies on a dark summer night. Were they from his thrusters? He blipped the control handle to trigger them, and jets of steam issued into space—but no particles. For the rest of the flight he would remain fascinated and mystified by these “fireflies” (on Carpenter’s later Mercury flight, they were discovered to be frozen water droplets from the spacecraft’s cooling system).

What Glenn did not know, as Friendship 7 drifted over the night side of Earth for a second time, was that mission controllers in Cape Canaveral were aware of a serious and potentially deadly problem with his spacecraft. It had to do with the landing bag, a tube of rubberized fabric that was folded, accordion-style, between the heat shield and the craft’s base.

Normally the landing bag would be deployed just before splashdown in the ocean; the weight of the heat shield would cause it to expand and inflate with air, cushioning impact with the water. But one of the many telemetry readings streaming down from Friendship 7 indicated that the bag had already deployed.

It was probably a faulty signal—but what if it wasn’t? In that case, the only thing holding the heat shield on would be the retrorocket package, which was secured by three straps attached to the capsule’s base. Once the retrorockets fired to slow Friendship 7 out of orbit, the retropack would be jettisoned, the heat shield would come loose, and when temperatures outside the capsule rose to 9,500 degrees during reentry, there would be nothing to protect John Glenn from incineration.

It seemed the only solution was to leave the retropack attached during reentry; its straps would burn away, but by that time aerodynamic forces would hold the heat shield in place. But while it was still attached, would it make the capsule unstable? And as it melted away, would it cause fatal damage to the heat shield? The anguish of uncertainty hung over Flight Director Chris Kraft and his team. They would have to come up with an answer before retro-fire time, which was less than two hours away. For now, Kraft decided, they wouldn’t say anything to Glenn. There was no point in worrying him with a problem he couldn’t do anything about.

The multicolored brilliance of another space sunset faded from view as Friendship 7 coasted into its third orbital night. Below, in the light of the full moon, Glenn could see a huge storm sprawled across the Pacific, with flashes of lightning going off like firecrackers all the way to the horizon. He was making as many observations and conducting as many tests as he could, including eye checks, which showed his vision was unaffected by weightlessness. The only strange thing was the questions he kept getting from the ground stations about his landing bag.

“John, leave your retropack on through Texas. Do you read?” It was Wally Schirra, from the ground station in Point Arguello, California. Glenn knew that in Mercury Control, people were deliberating about the landing, but right now there wasn’t time to dwell on that; retrofire was less than a minute away. He’d lined up the capsule to the proper attitude, with the retrorockets aimed 34 degrees above the horizontal, pointing into his flight path. With half a minute to go, the capsule’s auto-sequencer began its own countdown for retrofire. Friendship 7 was crossing the coast of California when Schirra read the final seconds: “Five, four, three, two, one, fire.”

Glenn felt a solid push as the first of three solid-fuel retrorockets began firing. His mission clock showed that since liftoff, 4 hours, 33 minutes, and 7 seconds had elapsed. Seconds later, he felt the second one go off, then the third. He felt as if he were suddenly flying back toward Hawaii, but it was just an illusion caused by the sudden acceleration after almost four and a half hours of weightlessness. In reality, the retros had only slowed Friendship 7 by about 340 mph, enough to cause it to fall out of orbit.

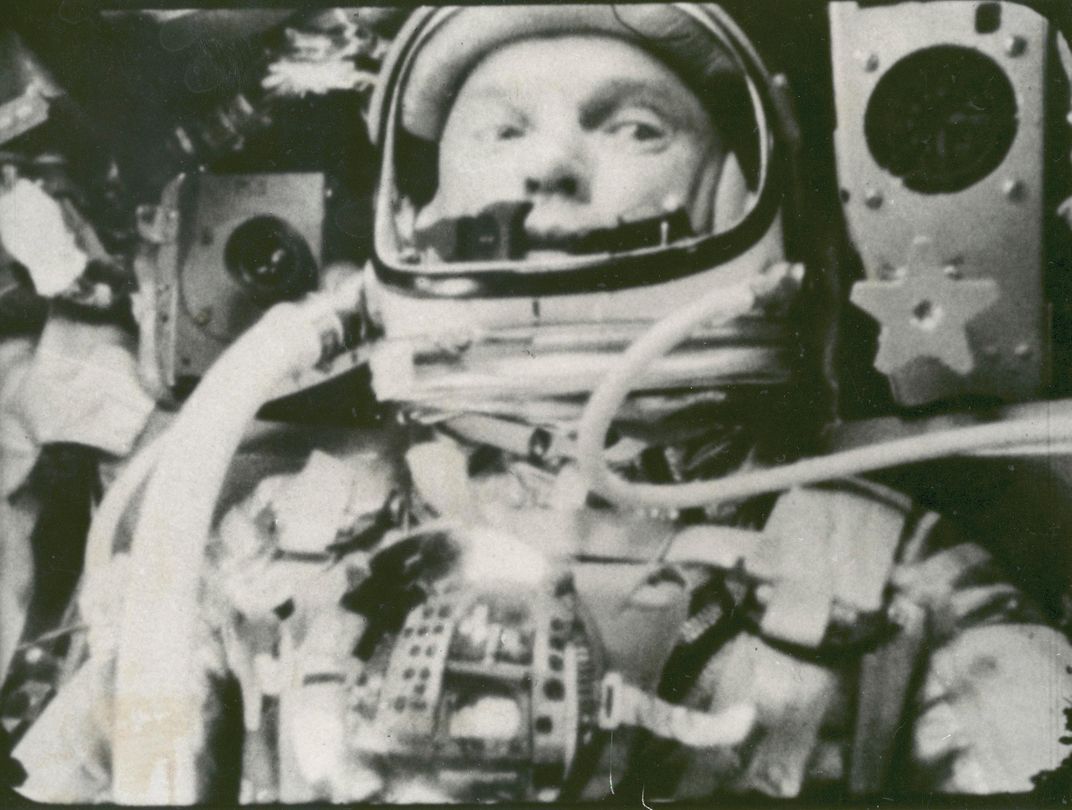

As Glenn flew within range of Cape Canaveral for the final time, Shepard finally told him what was going on: “We are not sure whether or not your landing bag has deployed. We feel it is possible to reenter with the retropackage on. We see no difficulty at this time in that type of reentry.”

“Roger, understand,” Glenn replied, hoping Shepard was right. He was now less than 59 miles up, the height at which meteors flash into visibility. He heard Shepard say, “Friendship 7, we recommend that you…,” and then the voice faded out. Glenn knew this was the start of radio blackout, as the capsule was enveloped in a sheath of ionized gas caused by the intense heat of its passage through the upper atmosphere. Less than half a minute later he heard a loud thump against the capsule. Through the window, he saw one of the straps from the retropack flapping around; then it burned away. A bright orange glow wrapped around the capsule and extended past the nose and into space. “This is Friendship 7,” he said, knowing his words were probably not getting through. “A real fireball outside.”

Big flaming chunks flew past the window. He wondered if the heat shield might be disintegrating. He knew that if it were burning through, he would feel the heat at his back, and he waited for it, every nerve charged with anticipation. Time seemed to crawl. He kept his eyes on the instruments, nudging the hand controller to keep the capsule oriented. He kept calling the ground—“Hello Cape, Friendship 7”—but there was no reply. Finally, after four and a half minutes, the blackout ended, and he heard Shepard’s voice once more as the orange glow diminished and disappeared. The heat shield had come through fine; the flaming chunks, he realized, had been pieces of the retropack burning away.

Now G-forces began to build as the capsule slammed into denser layers of air. As Friendship 7 cleared 110,000 feet, Glenn was pressed into his couch at eight times the force of gravity—no problem after all the practice runs in the centrifuge. Then the Gs slacked off again. Reaching the lower atmosphere, the capsule began to swing back and forth until the small drogue parachute deployed at 30,000 feet. Finally, at just under 11,000 feet, the main parachute came out and, with a jolt, blossomed into an orange and white canopy. “Beautiful chute!” called Glenn, relief and triumph in his voice as he felt the capsule’s descent slow dramatically.

Friendship 7 hit the water with a thump. In the periscope and through the window, Glenn saw seawater as the capsule momentarily submerged, tilted to the right and then the left before righting itself. He was down safely.

Late that afternoon, on the rescue ship USS Noa, Glenn found a quiet spot on the deck and dictated his observations about the flight into a tape recorder. Behind him, the sun sank toward the Atlantic—his fourth sunset of the day. Other than the heat shield worries, difficulties with the automatic control system had been the flight’s biggest problem. But that malfunction, in Glenn’s mind, had turned out to be fortuitous: By taking manual control and keeping the capsule oriented correctly, he had demonstrated the usefulness of a pilot in space, and that was his proudest achievement. From now on, he knew, NASA would have to think of the astronaut as an integral part of the spacecraft system, whether he was conducting scientific observations or steering his craft in this “new ocean,” as President John F. Kennedy would soon call it.

**********

Little did Glenn know that this was the end of his spaceflight career. It became clear to him by 1964 that he wouldn’t be assigned to another mission. (Decades later, he would hear unconfirmed reports that Kennedy deemed him too valuable to risk letting him fly again.) So he left NASA and didn’t look back, first becoming an executive with Royal Crown Cola and then, in 1974, winning election as a U.S. senator from Ohio. Glenn’s political career took him as far as a run for the presidency in 1984.

But throughout his 24 years in the Senate, space was never far from his mind. Glenn was known on Capitol Hill as one of NASA’s strongest supporters, and was a vocal advocate of the agency’s flagship program, the International Space Station. In early 1995, he was preparing for a floor debate on the space budget when he opened a NASA volume about the biomedical aspects of spaceflight. As he scanned one of the charts and saw the effects of long-term exposure to weightlessness—weakening bones and muscles, cardiovascular deconditioning, disturbed sleep, depressed immune function—it hit him that these were the same things that happen to the elderly. Had anyone else noticed? It turned out someone had—the head of life sciences at NASA headquarters, Joan Vernikos, who’d written a report describing the parallels between spaceflight and aging. The more he looked into it, the more Glenn began to feel that if NASA sent an elderly astronaut into orbit, important knowledge would be gained for both long-duration space travelers and Earth-bound seniors. And he thought, “Why not me?”

He had always longed to return to space, but Glenn had assumed that chance had been lost forever. Now, at the age of 73, he saw another opportunity. He wasn’t about to ask NASA for a free ride; he would have to show that there were good scientific reasons for sending a septuagenarian into space. He was already in frequent contact with NASA administrator Dan Goldin about the agency’s budget; now he started using those meetings to talk up the idea. At first Goldin thought he was joking. By the end of the year, however, as Glenn continued to raise the subject, telling him all about the conversations he’d been having with researchers at the National Institute on Aging, Goldin realized he meant it.

For the next two years, Glenn worked patiently to advance his cause. Finally, in January 1998, Goldin made it official: In October John Glenn would fly on the space shuttle Discovery, as part of a crew of seven, on a nine-day mission.

Glenn’s crewmates for STS-95 exemplified the new generation of astronauts, which included scientists, physicians, and engineers, many of whom had never flown an airplane before coming to NASA. Mission commander Curt Brown and pilot Steve Lindsay were both test pilots. Scott Parazynski was a physician by training who had come close to being selected as an Olympic athlete. Steve Robinson was a Ph.D. engineer and physicist. Rounding out the crew were two international astronauts. Chiaki Mukai had become Japan’s first woman in space with a 236-orbit shuttle flight in 1994. Finally there was the crew’s rookie, engineer Pedro Duque, who would become the first Spanish citizen to fly in space. The culture of spaceflight was a very different place in 1998 than it had been in 1962, when astronauts were white, male test pilots.

One thing hadn’t changed: John Glenn was still a hero, even within the walls of the astronaut office. When his new shuttle crewmates found out they were going to fly with the first American to orbit Earth, they couldn’t believe their good fortune. “It’s like getting a chance to play baseball with Babe Ruth,” recalls Parazynski.

Mission specialist Steve Robinson vividly remembers watching Glenn’s Mercury flight as a six-year-old; he drew a picture of the Atlas rocket and won second place in an art contest sponsored by the San Francisco Chronicle. Now, as the astronaut in charge of STS-95’s scientific payload, he was told he would oversee Glenn’s training. Robinson recalls his reaction: “I’m like, ‘I’m going to tell John Glenn anything?’ ”

Parazynski was even more intimidated by his assignment. As Glenn’s personal physician for the flight, he says, “My role weighed pretty heavily. If something happened to John Glenn up there, I might as well not come back home.”

As they began training, Parazynski says, “I expected to see a 77-year-old man with 77-year-old problems.” To his surprise, what he saw instead was a man in great physical and mental condition. It was remarkable just how little Glenn’s age showed. Still, his body wasn’t as flexible as those of his crewmates; he was reminded of that every time he had to go through the orbiter’s side hatch or fight his way into the pressure suit he would wear for launch and reentry. And like many older people, his night vision had diminished somewhat. Glenn decided to keep a flashlight tethered to his wrist for the times when he had to work in a dimly lit corner of the shuttle cabin. But those were about his only limitations, and in one preflight test to measure reaction times, he actually outperformed the rest of the crew.

STS-95 was one of the busiest shuttle missions ever, with 83 scientific experiments on the manifest. Several of them had Glenn as a test subject. He would swallow a pill-sized thermometer that would transmit data on his core body temperature to a monitor on his hip. While he slept he would wear a vest and headgear bristling with sensors to monitor his brain and body. And there would be blood samples—lots of them. (Getting them was Parazynski’s job; Glenn started calling him “Count Parazynskula.”)

What Glenn wanted most—other than to live up to his new responsibilities as an active-duty astronaut—was to fit in, to be one of the gang. His first day in Houston, he told his crewmates that they’d better get used to calling him John, not “Senator.” He needn’t have worried. In the surest sign of acceptance, they teased him mercilessly. When he was around Glenn, Parazynski never failed to mention that he was just seven months old at the time of Friendship 7, or to praise Glenn as a medical subject because it was so easy to apply electrodes to his bald head.

The rest of the STS-95 crew loved hearing Glenn tell war stories, and they stood beside him in the National Air and Space Museum as he pointed out his own handwriting on the instrument panel of Friendship 7. At the same time, recalls Robinson, “He’d had such a tiny little taste of spaceflight…. We were all curious to see what it would be like for him.”

**********

A dome of clear blue stretched over Cape Canaveral on October 29, 1998, as Discovery waited on the launch pad while the clock counted down. Lying in his seat on the mid-deck, with Robinson on his left and Mukai on his right, Glenn felt the same heightened awareness of what was about to happen—what he called “constructive apprehension”—that he’d experienced almost 37 years earlier.

With less than four seconds to go, the orbiter’s three engines ignited, sending vibrations through the cabin and causing the shuttle, still firmly bolted to the pad, to momentarily sway to one side. As it came back to vertical the count reached zero. With a roar from its solid rocket boosters, Discovery leapt off the pad. The ride was rougher than the one on the Atlas, until two minutes after liftoff, when the boosters separated with a blast of noise that surprised Glenn. After that, it was just a nice, smooth push until, right on schedule, the orbiter’s engines went quiet. Robinson reached out his gloved hand and said what no crewmate had been there to say in 1962: “Welcome to space, John Glenn!”

Zero-G took some getting used to. Glenn had worried that once he was able to float around, he might become one of the more than 60 percent of astronauts who suffer from space motion sickness. But he felt fine, and by the second day he knew there was nothing to worry about on that front. Getting around the spaceship was another thing. If he didn’t use just the right amount of pressure pushing off the cabin wall, he would set himself spinning. And for a while, he would bump his head as he moved around.

But none of that was different from what countless rookie astronauts had experienced, and before long Glenn was at ease in the weightless world. He even tried out a little rig that a couple of his crewmates set up at the end of the tunnel connecting the shuttle’s cabin to the SpaceHab module. On each side of the opening, they’d strung a bungee cord. By grabbing one bungee in each hand, pushing with your feet, and then letting go, you could launch yourself down the tunnel all the way to the shuttle cabin—if you didn’t bump into anything. Glenn did it perfectly—no surprise to Robinson, who understood that for a former Marine fighter pilot who’d experienced a catapult launch from a carrier deck, this was just a different kind of “cat shot.”

Being back in space after almost 37 years was even more wonderful than Glenn had imagined it would be. His first look out the window, over Hawaii about an hour into the flight, all but overwhelmed him. (Parazynski said years later, “I could’ve sworn I saw a little tear well in his eye.”) They were 310 miles up, more than twice as high as he’d flown in Friendship 7, and the view stretched 1,600 miles in every direction. Coming over Florida, with the Bahamas in a vivid swath of turquoise water, he could look to the north and see all the way to Canada. For a nighttime pass over South Africa, they all gathered at the windows to look down on a vast display of thunderstorms, with hundreds of lightning flashes piercing the darkness.

It amazed him to think that between his first flight and this one, the state of the art had progressed from his little Mercury capsule to this airliner-size spaceplane; almost the entire history of human spaceflight had elapsed. That afternoon, he was able to get up to the flight deck and see his crewmates use the shuttle’s robotic arm to deploy a small satellite. A couple of times, he’d even snuck up there by himself and floated into Curt Brown’s seat just to see what it felt like. He would have loved to command a mission like this.

Still, he was not about to complain. He felt hopeful now that he had cleared the way for other elderly astronauts to go into orbit (although none have), and had provided data that might help astronauts stay healthy on their way to Mars, and in the near-term, make life better for a graying America. For his crewmates, seeing Glenn achieve his dream of returning to space was something they would always remember. Late in the flight, Robinson recalls, “everybody was down on the mid-deck, finishing dinner or something. It was getting close to bedtime. And John wasn’t around. So I floated up to the flight deck. He had the lights off, and he was looking up through the window at the Earth, and there were thunderstorms down there. And I said, ‘John, what are you doing?’ And he said, ‘I’m at church.’ ”