Have Gun, Will Dogfight

On its 60th anniversary, pilots remember the Vought F-8 Crusader.

:focal(1141x543:1142x544)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/4d/784d4d11-c09b-4120-966a-96fb5543b915/11x_on2015_f8crusader3_live.jpg)

“The Last of the Gunfighters” sounds like a Gary Cooper movie or a Zane Grey novel. But the top result in a Google search for that phrase is the Wikipedia page for a six-decade-old jet fighter, the Vought F-8 Crusader. Adopted by the U.S. Navy in 1957, this single-engine, 1,000-mph dogfighter downed 19 MiGs during the Vietnam War and was an accurate, deadly strafer. Yet despite its service record, speed, and recognition for excellence—it won the 1956 Collier Trophy—the Crusader has fallen into obscurity.

Why? In a word that isn’t even a word: F-4.

Retired Marine Corps General Jack Dailey, the director of the National Air and Space Museum, flew the F-8 in the mid-1960s. “Everybody who flew that airplane loved it,” he says. “It was a single-seater, the way fighter pilots thought a fighter was supposed to be.” But upon Dailey’s arrival in Vietnam, he was assigned to an RF-4. He says the Crusader missed its war: It was too late for Korea, and by the time the Vietnam conflict got going, U.S. naval aviation was already well into its transition to the twin-engine, multi-role F-4 Phantom (see “Any Mission at Mach 2,” Feb./Mar. 2015).

With a top speed of Mach 2.2, the F-4 could intercept airborne threats to the fleet faster and farther from the ships than the Crusader could, and it had the ability to fire at an enemy head on. Also, that second engine gave the F-4 better survivability—critical for pilots flying in combat and over wide stretches of ocean.

Of course, the F-8 still had something F-4 pilots desperately wanted but didn’t get for several years: guns. Four of them, firing 20mm rounds.

“There was this strange idea in the Department of Defense that the gun was passé,” says military aviation historian Richard P. Hallion. “And the gun has never been passé.” Compared to the missiles of today, he says, the air-to-air missiles arming F-4s and F-8s during Vietnam were primitive and unreliable.

Peter Mersky, the author of F-8 Crusader Units of the Vietnam War, says that even though only two of the Crusader’s 19 MiG kills in Vietnam were made solely with guns, the F-8’s cannon were more than just a confidence booster for pilots. “The two official F-8 gun kills have since been augmented by other unofficially credited kills that used a combination of 20mm fire and a well-placed Sidewinder hit,” Mersky says.

The single-engine, single-seat F-8—originally the F8U-1 under the old Navy numbering system—was one of several aircraft born of the lessons of Korea, according to Hallion.

Former Senator John Glenn flew the F-8 as a U.S. Marine Corps major and test pilot at the naval air base at Patuxent River, Maryland, in the mid-1950s, and was an immediate fan. “I’d like to think what I could have done had I had it in Korea when we were flying against the MiGs, compared to the F-86s,” he says. “With four 20mm cannons, it would have been better armed than the MiG. In dogfights I don’t know that it would have been much better in ability to turn, but it would have been better at controlling the battle because it could go higher and faster.”

The higher, faster F-8 was the Navy’s answer to the Air Force’s supersonic air superiority stud, the F-100 Super Sabre. You could almost hear Vought lead engineer Russell Clark and the rest of the design team say “Oh yeah?” on March 25, 1955, when test pilot John Konrad took the prototype, XF8-U, supersonic on its first flight. The following year, Navy test pilot R.W. “Duke” Windsor took the Crusader to 1,015 mph, a national speed record and an achievement that took the postwar Thompson Trophy away from the F-100.

Glenn, who was in charge of F-8 armament testing, recalls early problems with the cannons mounted on the side of the engine duct at the front of the aircraft. “When we fired the gun on the ground at a target it did okay, but when we did a two-second burst-fire with all four guns, the duct would flex and you had a big circular random pattern.” Vought beefed up the duct for later aircraft, but the initial solution was to send a cross-eyed airplane to the fleet. Glenn says, “To make up for that flexing we [made it] so when you looked down the boresight on the ground it was cross-eyed to the other side. We [adjusted the boresight by taking] the average of how far they were off-target when we did the two-second burst-fire.”

In 1957, Glenn famously completed Project Bullet, briefly stealing the transcontinental speed record back from the Air Force by flying an F-8 nonstop coast to coast in afterburner the entire trip, except during the three aerial refuelings required.

Slowing the first fighter capable of flying faster than 1,000 mph to a safe speed for landing on a carrier deck required ingenuity, and the solution to that problem is one of the reasons that the National Aeronautic Association awarded the Collier Trophy to Vought and the Navy in 1956. Vought’s team designed a “variable-incidence wing”: Hinged at the rear, it adjusted its angle relative to the fuselage. The ability to increase the wing’s angle of attack while keeping the fuselage level gave the pilot good visibility for takeoff and landing, and the increased lift needed for the slower speeds those regimes demanded. Even with the braking effect of this design innovation, the Crusader landed fast, and putting it down safely on the deck of a carrier required great skill.

Fleet pilots couldn’t wait to fly the F-8, although their initial experiences ranged from sheer exhilaration to sheer terror. Don “Frazz” Fraser, a Marine pilot who started flying the F-8 in 1959, remembers his first flight: “There were no simulators in those days. You strapped it on and hoped you had it all right. I was just so excited to fly an afterburner aircraft, hitting the burner and getting airborne like a jackrabbit. You had to be very careful…you had to roll in trim to keep the nose down. If you didn’t do that and bring your wing down before accelerating, you could shed your wing right off.”

But if takeoffs were exciting, landings were another thing altogether. The Crusader quickly gained a reputation as an “ensign killer.” Pilot Joe Phaneuf recalls the tension raised by the F-8’s high landing speed: “The [aircraft carrier] always had to make maximum knots to get the most wind across the deck to make the relative landing speed slower than the actual aircraft speed. The old carriers burned coal, and the blackest, stinkiest smoke would settle right behind the ship so you couldn’t see.” Flying toward the flight deck and listening to the landing signal officer say “Keep it coming” was an exercise in trust.

In 1957 John “Crash” Miottel transitioned from the FJ-2 Fury (a beefed-up, carrier-capable version of the Air Force F-86) to flying the F-8 off Hancock. He says the early aircraft had lightweight landing gear that broke a lot. To make matters worse, “the port strut served as a reservoir for hydraulic fluid, so if you lost the landing gear and got airborne again, you had to go to the backup ram air turbine [to keep your flight controls working]. Trying to land with a broken landing gear was not really desirable.”

Miottel had a tailhook malfunction during landing, flying his disabled F-8 into a barricade erected on the flight deck. He describes the barricade as a “heavy-duty 20-foot-high tennis net” and the aircraft as a “multi-ton tennis ball on a 150-mph bad serve.” Everything went fine until the barricade tore off his left landing gear; the aircraft pivoted on its left wingtip and headed off the port side of the carrier. Miottel managed to jettison his canopy and yank a handle that released him from the ejection seat as he plunged into the water, and he jokes, “The old aviators’ maxim that ‘Any landing you can walk away from is a good landing’ was amended to incorporate the words ‘or swim.’ ”

Rear Admiral Bob Shumaker (ret.) also had an adventure involving a recalcitrant tailhook and a night landing during a Mediterranean cruise on the Saratoga in 1960. After making three landing attempts with a tailhook that wouldn’t come down, he says, “they told me to head to Italy, but I didn’t have enough fuel so they said to join the tanker. I found the tanker and my heart was beating a little faster by then and the tanker said, ‘I’m flipping every switch in here but I can’t get the hose to come out.’ That was strike number two.”

For strike number three, Saratoga’s flight deck barricade wouldn’t deploy. Shumaker was running out of options: “I was down to 200 pounds of fuel. I climbed to 3,000 feet and punched out and strike number four was the parachute didn’t open…. I pulled the D-ring to manually deploy the chute and nothing happened, but pulled harder and it finally opened.” A nearby destroyer picked him up and ingloriously returned him to the carrier.

F-8 operations could be scary for the ground crew as well. John Borry, a plane captain and jet mechanic with VF-13 aboard Shangri La, didn’t like crawling down the engine intake. “That’s a good 20 feet long on the inside,” he says. “Sometimes someone would stand behind the airplane and start whistling through the tailpipe like the engine was starting and you’d scramble out of there real quick!”

The F-8’s giant air intake earned it another nickname: Gator. “That intake is down so low you couldn’t walk anywhere near the front of the airplane,” says Borry. “One day another guy got too close and it started to suck him in, but I grabbed his ankles and signaled the pilot to shut the engine down.”

Still, mechanics loved the F-8. Jay Powelson remembers his favorite job was engine runs: “Nothing can compare to an F-8 afterburner shot because it just jars the whole airplane and you hope the chain is going to hold.” The afterburner on the F-8 was an all-or-nothing affair, unlike the staged afterburners on newer aircraft. When F-8s arrived on the Constellation to the care of plane captains and mechanics who had worked only around F-4s, says Powelson, “Four or five guys hit the deck when the F-8 lit the afterburner. They thought something had blown up.”

Louis Zezoff, a maintainer on the Coral Sea in 1961-1962, remembers watching the aircraft maneuver: “There wasn’t a lot of rules and regulations back then…. The pilots taught themselves. The pilots couldn’t wait to get in the seat and fly off the carrier. They called it the sports car of the Navy.”

But even great fighters can be pushed too far, as Shumaker learned on his sixth flight in the F-8: “We were over Gainesville, Florida. There were a lot of clouds and we got up to 55,000 feet. As we started to turn around, we were slow, and the airplane spun on me and I went into the clouds. I got out of it after I think 14 rotations and I lost about 25,000 feet so it was pretty exciting.”

Intercepting targets in the F-8 involved art, not just finding a blob on a radar. According to Shumaker, the F-8 radar could see a target at only about eight miles. “A controller on the ship would call out the direction and distance of a bogey and we would manually figure out how to intercept. It took a lot of technique. Our weapons were forward firing, you had to get in the rear hemisphere of the target to launch.”

By the early 1960s, most of the bugs in the F-8 had been worked out and the fighter was ready for war. (Two unarmed reconnaissance variants, the RF-8A and RF-8G, saw action beginning with the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 and throughout the Vietnam War.) The E model could carry 4,000 pounds of external weapons such as bombs, so it served as an air-to-ground attack platform as well as a fighter.

Not everyone was enamored of bombs on a high-wing aircraft. Jem Golden, an ordnance man on the Shangri La in the late 1960s, says, “We only had two guys in the shop who were tall; the rest of us were five-eight, five-nine, standing on tiptoes trying to get these 500- or 750-pound bombs up there. The other squadron would come over and help, and there’d be 10 guys trying to get one bomb loaded. We were cussing the whole time at the guy in the Pentagon that thought this one up.”

The F-8 saw early action in Vietnam, including the February 1965 Flaming Dart operation, two strikes to retaliate against the Viet Cong for attacks on air bases and a hotel that housed Americans. Shumaker, flying off the Coral Sea, got the call for his first combat sortie: attack barracks at Chanh Hoa, just north of the demilitarized zone. “I rolled in on the target,” he recalls; “I was flying low because of the weather and they nailed me in the tail section and the plane flipped upside down and nose down and I got out and the parachute opened about 35 feet above the ground.” He was captured and spent eight years as a POW. He never flew the F-8 again.

Phaneuf flew 208 combat missions off both the Ticonderoga and the Oriskany. He says the diciest missions he flew were Iron Hand—escorting attacks on surface-to-air-missile sites. “[We’d] fly wing for an A-4 attack pilot who was armed with anti-radiation missiles. I was armed with anti-personnel rockets as well as Sidewinders. [We’d] fly off the ship [and] drop down low on top of the water to avoid the enemy radars until feet dry [over land] and zoom climb to 18 or 20 thousand feet. [Then our] anti-radar warning gear started chirping. An A-4 would lock his missile onto the radar site and launch. I would hit the afterburner and follow the missile as it looked at the SAM site. The missile would take out the radar van and then my job was to shoot my rockets so it saturated the whole missile site to put it out of commission.” But “our squadron was always first on the target,” he says. “The first group in absorbed the flak and the SAMs and we never saw a MiG. The second group bagged quite a few.”

Commander Hal Marr, flying off the Hancock, got the first F-8 kill, knocking down a MiG-17 with a Sidewinder on June 12, 1966. Nine days later, Lieutenant (JG) Phil Vampatella hit a MiG-17 with a Sidewinder and Lieutenant Eugene Chancy got the first MiG kill with a gun. All three pilots were in fighter squadron VF-211.

Marr described his MiG engagement in Mersky’s F-8 Crusader Units of the Vietnam War. Flying with Vampatella on his wing, “We pull hard into them and the fight’s on,” he recalls. “Two MiGs split off, and we pass the other head on.” After missing twice with his cannon, he was 1,000 feet above the MiG when he tried firing a Sidewinder, “but the missile can’t hack it and falls to the ground. The MiG has been in ’burner for four or five minutes now and is mighty low on fuel, so he rolls and heads straight for his base. I roll in behind, stuff it in ’burner, and close at 500 knots. At a half-mile, I fire my last ’Winder, and it chops off his tail and starboard wing.”

Marr’s kill was a typical F-8 engagement: The aircraft was a true dogfighter from the rear. Again, the F-8 had to be within visual range to engage, unlike the newer F-4, which could engage the enemy from longer ranges with its radar-beam-following Sparrow missiles. In addition, the F-4 required two crew members. Mersky says that Vought marketers dreamed up “Last of the Gunfighters” when they learned of the F-4’s lack of internal gun and its two-crew concept, and fleet pilots quickly picked up the name and developed a friendly rivalry with their F-4 counterparts.

Although both Air Force and Navy F-4s were eventually equipped with guns, the nickname stuck. By the end of Vietnam, F-8 pilots claimed the highest kill ratio of any aircraft of the war: 19 MiGs downed to only three F-8 losses.

Of course, those statistics also reflected the relatively low numbers of F-8s in the fight. “F-8 pilots, although ready and able, did not see as many MiGs throughout the war as their F-4 compatriots,” Mersky says. “There were many more Phantom squadrons than Crusader squadrons in action in Vietnam. Certainly by 1971, there were only three Crusader squadrons.”

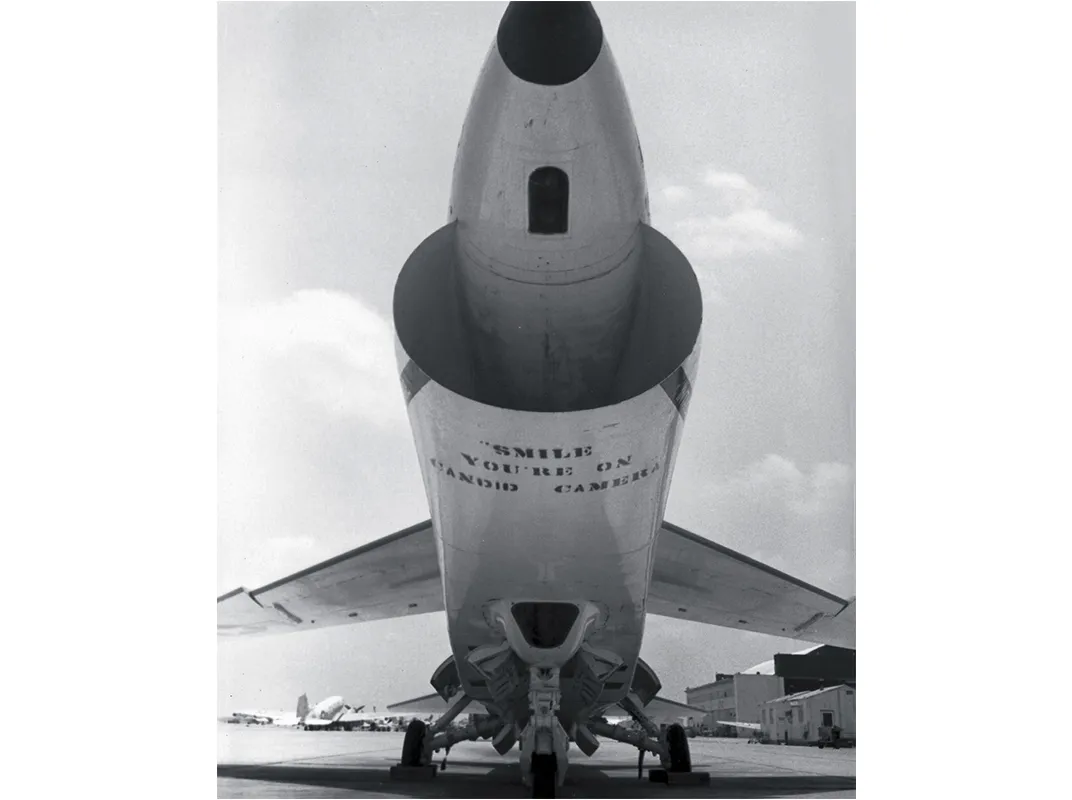

But the F-8 had a record outside of Vietnam as well. John Borry recalls slinging unusual ordnance one day in the Mediterranean in 1967: “The Russians had a trawler dogging us all the time, especially when we were launching aircraft, to try to mess us up. The skipper got angry one day and told us to get 13 rolls of toilet paper. He lowered the speed brake, which is underneath the belly of the airplane, and it held the toilet paper [in holes in the metal]. He flew over the trawler and opened the speed brake and 13 rolls of toilet paper came streaming down. They had antenna arrays everywhere and it looked like someone’s house at Halloween, but they loved it! They were waving and hollering at us because they didn’t have toilet paper on their boat.”

In the literal sense, the “Last Gunfighter” nickname was a misnomer. The F-4 was modified to carry guns, and subsequent U.S. fighters all have internal guns. But those aircraft also have multiple weapons that can kill an enemy the air crew never see, except on a radar scope. The F-8 was something else.

As Zezoff says, “you had to be well within sight [of the target] and it was you against that other pilot and it was like you were standing on the streets of Dodge, eye to eye.”

Powelson is more blunt: “F-8s were designed for dogfighting. The F-4 wasn’t.”

In his book MiG Master: The Story of the F-8 Crusader, historian Barrett Tillman elaborates: “Of the American aircraft which flew regularly over the north from 1965 on, only the F-8 could be called a true air-superiority fighter…. Interceptors and fighter-bombers can each successfully perform the [dogfighting] role, but not as well as an aircraft dedicated solely to that mission. This was the difference between the F-8 and every other American aircraft that operated over North Vietnam.” Tillman concludes, “Crusader pilots were fighter jocks, by God, with no ifs, ands or hyphens.”

Today, the Crusader lives on in museums and websites devoted to its legacy. Craig Wall, a retired Air Force mechanic, is restoring the prototype, XF8U‑1, in which John Konrad made the first flight 60 years ago. The aircraft came from the Smithsonian in the mid-1990s and sat outside at the Museum of Flight in Seattle for a number of years, picking up corrosion. Wall has worked on the airplane since 2001, and it is now painted exactly as it was during the first flight.

But the sun set relatively quickly on the F-8. With two engines, the F-4 paved the way for air superiority aircraft like the F-15, the F/A-18, and the F-22.

Meanwhile, rapid advances in ship design—longer, angled decks and steam catapults that could launch heavier aircraft than hydraulic cats could—made it possible for supercarriers like the Forrestal, commissioned in 1955, to carry squadrons of F-4s, faster and more powerful, if less agile, than the gunfighting Crusaders. Ultimately, the F-8’s tenure as an American war-fighting aircraft was only about half as long as the career of the F-4, which served through the first Gulf War and wasn’t retired until 1996.

Had it not been succeeded by a more adaptable and longer-lived aircraft, the F-8 would likely be a lot more famous today. But its legacy is haunted—by a Phantom.