Birth of the Cobra

Mike Folse proved that a helicopter could fly and shoot at the same time.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c7/fc/c7fc744c-ab35-4db7-8338-362734ba30cc/13r_jj2017_n209jwilhiteviabellhelicopterhistoricalarchives0102_ah-1g_live.jpg)

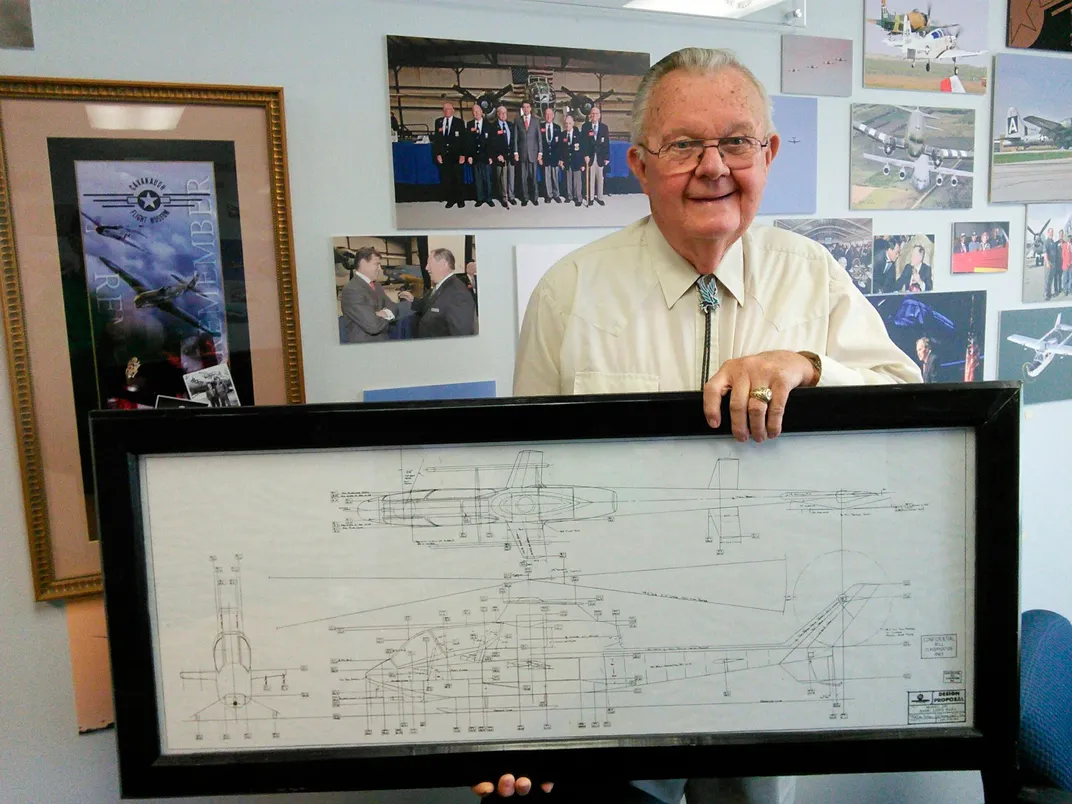

What was on Mike Folse’s drawing board at Bell Helicopter that day in March 1965 was supposed to be a hovercraft. It wasn’t. “I had an idea instead,” he explains. “My boss would be on vacation for two weeks.”

Gloom pervaded Bell’s Preliminary Design Group. In a Pentagon competition to develop an ambitious concept for an attack helicopter, Bell’s proposal had just lost out to Lockheed’s—a demoralizing beat-down from an airplane company that had never made a helicopter. At Bell’s Hurst, Texas plant, an exodus was under way as dispirited engineers and executives started burning up accrued vacation time. On his way out the door, Folse’s boss issued explicit instructions: “Forget what you’re working on. While I’m gone, start on a hovercraft.”

The youngest design engineer ever hired at Bell, Folse climbed the ladder in the 1950s, working on projects ranging from the “goldfish bowl” Model 47 light helicopter, for which he was a flight test engineer, to designing airframe components for the UH-1 “Huey”—the most-produced U.S. military helicopter in history—to development of the 206 JetRanger.

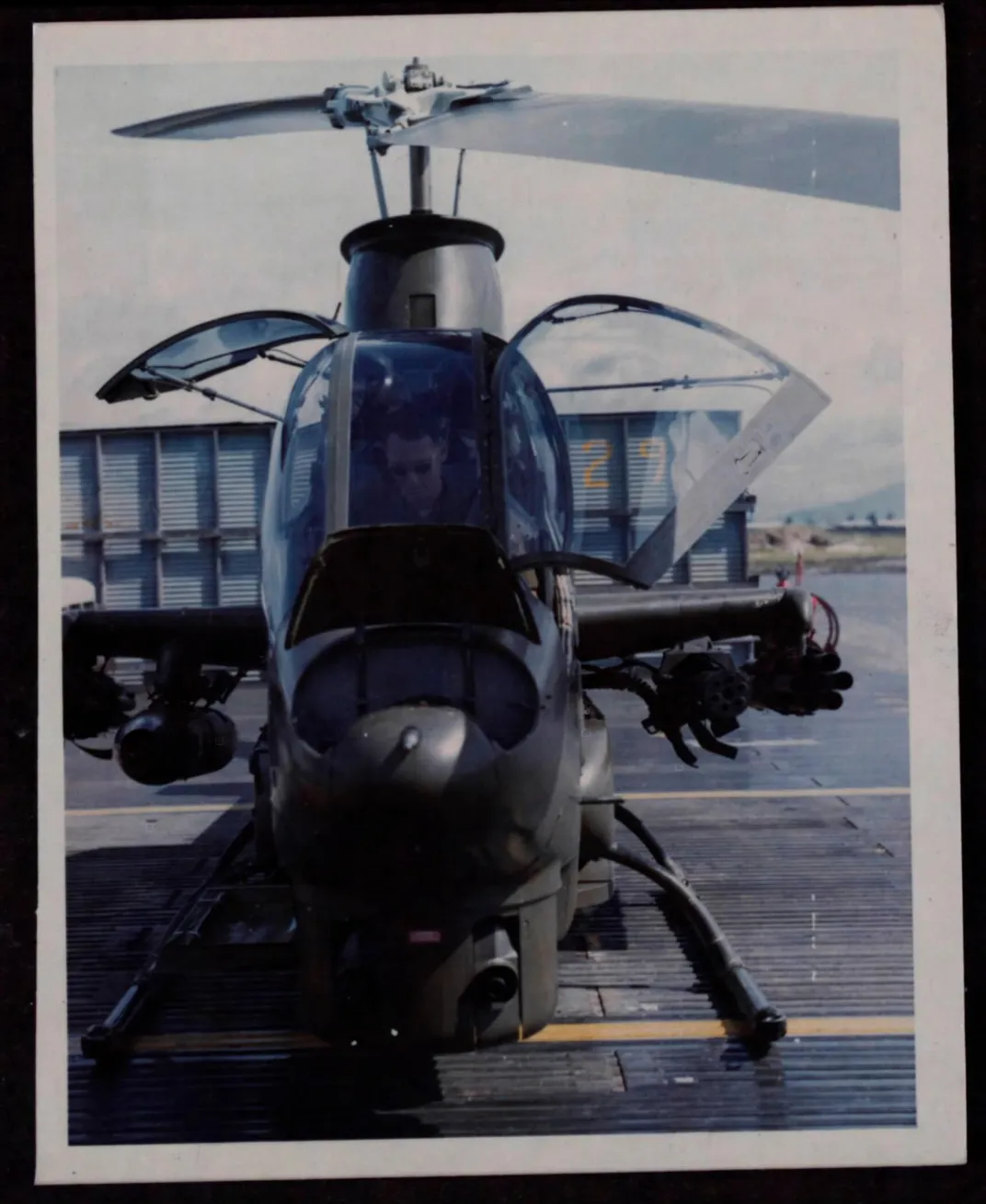

Now among a skeleton staff in the design group that March, Folse took out a sheet of vellum paper and began rendering the sleek outlines of what would become the Bell AH-1 Cobra, the world’s first production attack helicopter. Designed, built, and deployed to the battlefield in just over two years from that day, the Cobra at last gave the rotary-wing genre a combat game-changer, purpose-built for offense.

**********

In the early 1940s, practice bombs were heaved from hovering Sikorskys. In 1950, Bell engineers borrowed a bazooka from the U.S. Army, mounted it on the landing skid of a two-seat copter, and nailed ground targets on a test range. During the Korean War, piston-powered U.S. “egg-beaters” inserted troops and arms into combat zones, and little whirlybirds evacuated the wounded. In 1962, the Howze Board, a Pentagon study group, recommended creation of an Air Cavalry Combat Brigade as well as development of new rotary-wing aircraft specific to the air mobility mission.

Two years later, a dedicated attack helicopter was on nobody’s assembly line.

As the Vietnam War escalated, Bell Hueys were deploying in increasing numbers, mainly in transport and medevac roles. Though Huey gunship variants came equipped with side-door machine guns and rocket pods, the “UH” designation stood for “utility helicopter”—and all the inherent trade-offs. “They couldn’t fly over 90 miles per hour,” says Folse. “They could barely keep up with the troop transports they were supposed to protect.”

Interservice rivalry was part of the reason, says Roger Connor, curator of vertical flight at the National Air and Space Museum. Providing close air support to ground troops was a traditional Air Force role. Says Connor: “So the Air Force basically said to the Army, ‘You can have certain aircraft, but only as long as they’re the equivalent of flying jeeps or trucks. Any functions other than that are purely an Air Force responsibility.’ ” The Army, conversely, viewed the Air Force as unwilling or unable to provide timely, specialized air support for flash firefights. “It would take 30 minutes or more to get effective Air Force close air support,” says Connor. “Fixed-wing support just didn’t work in Vietnam.”

Connor notes that when the French mounted weapons on U.S. helicopters to fight Algerian rebels in the late 1950s, the Army paid close attention. So did Bell. By 1962, a confidential Bell project culminated in the D-225 Iroquois Warrior concept. In an era of clunky workhorse helicopters, the D-225, with its slender fuselage, two-place tandem seating, and nose-mounted gun pod, looked futuristic.

The buzz generated when Bell began shopping a Warrior mockup around to Army decision-makers, however, rankled other helicopter makers, who complained that the company was circumventing competitive rules. Washington responded with a formal request for proposals soliciting designs for an Advanced Aerial Fire Support System (AAFSS). Seven aircraft companies, including Bell, responded.

The specs called for a 200- to 250-mph attack helicopter with overwhelming armament capacity. Lockheed’s AH-56 Cheyenne design promised it could meet those demands. Bell’s proposal, meanwhile, not so much. Based on the Warrior concept, “we spent six months writing it,” says Folse. “And it was a terrible proposal. I know, because I worked on it.” Lockheed’s design swept the competition, and Folse’s boss left on vacation.

Many at Bell estimated that Lockheed, with no background in rotary-wing R&D, would require three to four years, minimum, to morph its complex Cheyenne concept into a combat-ready production model. Meanwhile, the lives of U.S. troops in Vietnam would be jeopardized. “This was unacceptable,” Folse says today.

At his drawing board, he began with a company photograph of a UH-1. “I traced the Huey’s rear end and tail boom,” says Folse. As his “idea” evolved on paper over ensuing days, it caught the eye of Bell’s director of military marketing. Folse explained his rationale for the design. Per government regulations, the Army couldn’t buy an all-new original helicopter without triggering the requirement for a formal design competition involving every other company: Been there, done that, lost. However, the military could buy a modification of a pre-existing helicopter model—no contest required. Huey models A through F were already on the Army’s shelf, so Folse said, “Why don’t we build this as the G model?”

It was a stretch. The three-view drawing that Folse penciled conveys little of the Huey’s utilitarian persona. It is, instead, a stark expression of speed and menace. Huey DNA is discernible in the tail rotor, but boom and tandem seating are Warrior-esque. Most everything else—from the main rotor forward—conjured a new world in rotary-wing warfare, not tweaks to the status quo.

Folse’s three-view is labeled “Model 209,” the copter’s in-house designation at Bell. Since the 1950s, Army helicopters had typically been named after Native American tribes. However, the first Army UH-1 Huey unit dispatched to Vietnam called itself the “Vinh Long Cobras” due to the high population of the snake species in that rural district. The serpent-specific call sign quickly caught on as shorthand for armed helicopters. Model 209 was thus formally dubbed Huey Cobra by the Army—which had a political stake in stressing the 209’s connection to previous Huey models. In the field, the new aircraft became simply Cobra.

Inside the Cobra’s structure, Folse accommodated the UH-1’s dynamic systems, Lycoming T53 engine, and other constituents, ensuring that 80 percent of the new ship’s components already had Huey part numbers in the government’s inventory. Enough to call it a model G—sort of. Pay no attention to the radical 36-inch-wide fuselage (a spec Folse got by measuring a Royal Air Force Spitfire), the novel retractable landing gear, or the accommodations for advanced integrated armaments. Ignore the 200-mph dive speed and flush rivets to reduce aerodynamic drag.

The marketing VP took the drawing straight to Bell Helicopter president E.J. “Duke” Ducayet. Two hours later, Folse was summoned to the president’s office—“I’d never been down there to Mahogany Row,” he says—where his sketch was prominently taped on the wall. Ducayet told him, “Mike, I just talked to Textron [Bell’s parent company] and got $800,000 to build that ship you designed. We’ve got six months to do it.” On the spot, Folse was promoted to experimental projects engineer on the Cobra.

Recounting the experience now, 83-year-old Folse shakes his head: “I just don’t think anything like that could happen today.”

**********

“If anyone ever tells you ‘I hovered the Cobra and fired rockets and mini-guns at the enemy,’ they’re not telling you the truth,” says Bob Hesselbein. “You didn’t hover in a Cobra—not in Vietnam.”

Hesselbein, former president of the Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association and a retired Northwest Airlines pilot, flew the “Snake” with Army Air Cavalry units in Vietnam in 1972. “It was wild flying,” he says. “Lots of airspeed. Basically the closest thing to the way guys flew fighter planes in World War II.”

Front seat or back? Both had flight controls. “It depended on your ego,” says Hesselbein. Both were classified as pilots, but the guy in back was aircraft commander, “so of course you were dying to sit in the back seat. On the other hand, the front seat gave you that superb visibility.”

All Cobra pilots were volunteers, qualified in the Huey. But not all Huey pilots aspired to fly the Cobra. Walker Jones, a back-seater for the First Air Cavalry in Vietnam, profiles the personality: “Cobra pilots tended to be take-charge types. We were the ones who wanted to shoot. We had the most responsibility, day to day, of any other helicopter pilot in the Army.”

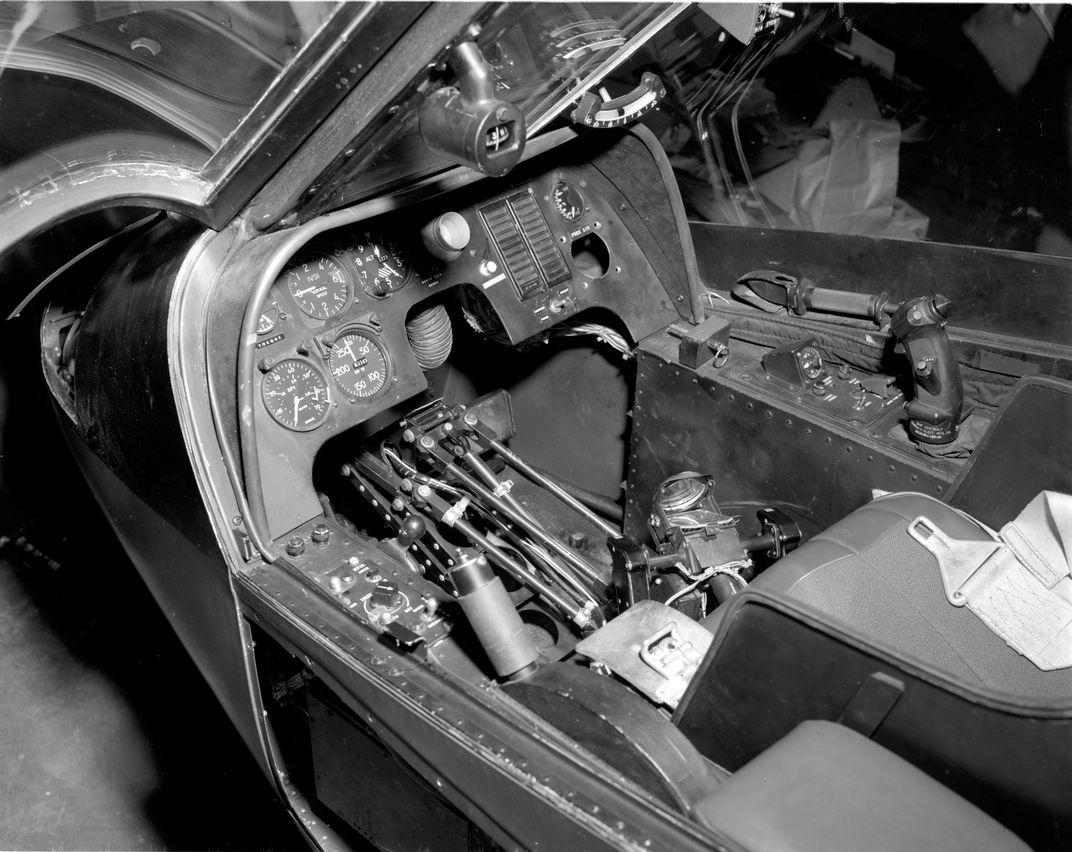

Vietnam-era armament included a rotating chin turret incorporating a General Electric six-barrel mini-gun and 40mm grenade “chunker,” aimed with a Pantograph sight operated by the front-seater. Folding-fin 2.75-inch rockets in pods mounted on the Cobra’s stub wings were launched by the back-seater, who also typically piloted the aircraft.

Cobras would launch with twice as much ammunition as Huey gunships, would get to the target in half the time, and could linger there three times longer. Arriving early and leaving late allowed Cobras to prepare the zone before Hueys landed, riddling the area with mini-gun fire and spreading smoke, then supporting “troops in contact” by shooting at the enemy.

“In 1972, we generally went out as a team of two or more Cobras,” says Hesselbein. “Rarely alone.” Rolling in on the target, the front-seater suppressed ground fire from the mini-gun. Approaching the release point, he held fire while the back-seat pilot launched rockets. As the Cobra pulled out of its dive, the front-seater re-engaged with the mini-gun “until the nose was so high that you couldn’t shoot down into the area,” says Hesselbein. The idea was to keep enemy heads down with the mini-gun, get rockets into the target, and get out. “You shot so much that after a while you didn’t bother with the pipper sight on the mini-gun anymore,” he says. “You’d just walk that fire hose of bullets right where you wanted them.”

Cobras also worked in hunter-killer teams. The hunter half, a Hughes OH-6 scout helicopter (known as “Little Bird”), circled like bait at treetop level while one or two killer Cobras orbited high overhead. “The enemy was terrified of Cobras,” says Walker Jones, “and sometimes wouldn’t shoot at Little Bird. They had to trick them into shooting.” If concealed ground troops could be lured into opening fire and giving away their position, the observer in the scout marked the spot with a smoke grenade. Then Little Bird got out of the way. That wasn’t the place to be when Cobras dove in, 4,000-rounds-per-minute mini-guns blazing and Hydra anti-personnel rockets streaking ahead.

Pilots sat in tempered-steel seats and wore 22-pound “chicken plate” body armor. “They shot down a lot of Cobras,” says Hesselbein. “But we didn’t feel greatly endangered.” He notes that other helicopters in Vietnam took far more casualties. The Cobra shared vulnerabilities with every helicopter type: Hits to the tail rotor drive shaft and to the main transmission—between the engine and the rotor—were fatal.

Enemy troops accustomed to the slower, wider-profile Hueys, however, were notably unskilled at targeting a razor-thin, 165-mph helicopter. “I got shot at a lot,” says Walker Jones. “I’ve seen several hundred AK-47 muzzle flashes shooting up at me. I still can’t believe it, but not one of them ever hit me.” Russian-made .51-caliber machine guns were more effective, however, and shoulder-fired missiles introduced later posed a substantial threat, downing 10 Cobras during the war.

**********

“The Bell plant had a U.S. Army office on the premises,” says Dan Sewell. “But we kept this entire project secret from them.” The project was concealed behind 16-foot walls erected in a hangar at the rear of the factory. Bell president Duke Ducayet visited daily. “The Army didn’t have a clue what we were doing,” says Sewell. During the spring and summer of 1965, he worked on the fast-tracked build of “ship one,” designing most of the Cobra’s all-new cockpit, including the tandem seats and front and back instrument panels.

“There were about eight of us engineers out there,” says Sewell. “And the process of building that first Cobra went very smoothly.” Starting with the tail boom of a Huey, they used the UH-1’s tail rotor, drive shaft, transmission, and engine. “Then we built from scratch everything from the front end of the tail boom up to the nose,” he says. “All of that was new on the Cobra.” Visual impact was also critical. “Bell really wanted everything about it to look sleek and very fast—more along the lines of a jet fighter than a helicopter.”

Ahead of schedule and within five percent of budget, “we flew in five months and 28 days from the day we started,” says Folse. On August 28, 1965, ship one, by then known as Model 209, was placed on a flatbed truck, covered with a tarp, and hauled to an empty former American Airlines facility at Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Field. After engine run-up tests, Bell test pilot Bill Quinlan pulled back the cyclic and lifted off one week later. About 20 high-ranking Army observers now privy to the project witnessed the 10-minute flight. “The government got interested real fast,” says Folse.

After more test flights and armament integration, a Bell pilot flew the fully equipped Model 209 from Hurst to Fort Bragg in North Carolina, with Folse in the front seat. “One of the biggest experiences of my life,” he says. After they landed, a black limo pulled up and General William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara stepped out and enthusiastically inspected the ship. Bell was still nimbly positioning it as a “modified UH-1,” strictly an interim weapons platform until Lockheed’s AH-56 Cheyenne became viable. Says Folse: “We told them right off, ‘We can have a production Cobra in Vietnam in one year. With Lockheed, you’ll wait at least three years before you get anything.’ ”

Other helicopter makers wanted a piece of that interim action. To select the most worthy candidate, the Army mandated a fly-off at Edwards Air Force Base in southern California. “All a bunch of junk,” Folse says of the rival lineup. Boeing Vertol offered its heavy-lifting Chinook, and Sikorsky brought a twin-engine SH-3 Sea King. “Can you imagine aircraft that large as an attack helicopter?” Folse laughs. Hiller and Kaman also submitted entries. “The Cobra just ate them all up,” says Folse. “Six days later, we got a contract to build 110 production Cobras.” By the end of 1966, the contract was increased to 500. After the fly-off, the ship shed its utility “UH” designation and was classified AH-1—“A” for “Attack.”

Model 209 embarked on a demonstration tour equipped with a unique marketing gimmick. A cobra at the Fort Worth zoo had died of natural causes. “We got the head and had it fiberglassed, then mounted it on the collective stick in the front cockpit,” says Sewell. “It was a big hit.” Other Cobra swag passed out at demo flights included realistic rubber snakes.

Meanwhile, rethinking continued as ships two and three emerged from the Bell factory and entered flight testing. Folse’s unique retractable landing gear was an early casualty. The gear was fully functional, but Sewell says some were concerned that when landing on rice paddies in Vietnam, the landing gear bay could be inundated with mud. Another fear: that chopper pilots habituated to fixed skids might accidentally land gear-up. Bell test pilot Joe Mashman did just that in Model 209 at the 1967 Paris Air Show. Other tweaks included a wider rotor, replacing too-heavy bulletproof canopy glass with plexiglass, and deleting the Cobra’s innovative umbrella-shaped dive brake after it self-destructed during its first test flight.

Another test at Fort Hood produced tragedy. “I should have been dead that day,” Folse says grimly. When a phone call from the Pentagon took him out of ship two’s front seat, another Bell employee replaced him. Moments later, the rotor assembly failed in flight, and the rotor sliced through the canopy, decapitating the front-seater and knocking the back-seater out of the cockpit in mid-air. Despite extensive post-crash investigation, the cause was never established. Says Folse: “The program continued on.”

The first Cobras arrived in Vietnam—12 AH-1Gs airlifted to Bien Hoa in C-133 Cargomasters—on August 29, 1967, almost exactly two years after first flight. By then, the Lockheed Cheyenne’s projected entry into service had slipped as far as five years into the future. (Ridden with technical difficulties and cost overruns, the Cheyenne project was canceled in 1972.) Within days, another 214 Cobras were ordered, at a total cost of $60 million. Training of the first pilots—the “Playboys” of the 334th Assault Helicopter Company—began immediately, and not a day too soon. On January 31, 1968, in one of the opening strikes of the Tet Offensive, Bien Hoa was hit hard.

**********

Piloting a 1980s chopper like the Black Hawk sounded fun, says Floyd Werner, “but you can’t shoot back like you can in the Cobra. I said to myself, ‘I think I’d like to shoot back.’ ”

Fifteen years after deployment of the AH-1G to Vietnam, Werner flew the AH-1F modernized Cobra in Desert Storm and later Bosnia. “You could tell you had strapped on a manly piece of machinery,” he says. Mike Folse’s aerodynamic stylings—and the trademark assertiveness of the Cobra pilot—were unchanged.

However, before they were shrink-wrapped and shipped to the Mideast, the Cobras were modernized with 500 new horsepower and evolved technology. Cockpit instrumentation was compatible with night vision. With ground threats now far more sophisticated than small arms, the AH-1F flew with an infrared jammer, a radar jammer, and a hot plume exhaust suppressor to foil heat-seeking missiles.

Desert Storm missions of 1990-1991 were typically a scout weapons team consisting of one Bell OH-58 Kiowa scout helicopter and one Cobra. “Low and fast, exciting and exhilarating,” says Werner. He flew the First Cavalry Division’s first combat mission in Desert Storm, establishing a line to create a demilitarized area between Kuwait, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia and holding it for 37 days, 24 hours a day. He recalls entire days flying the Cobra in the back seat, wearing a flightsuit and full chemical warfare gear, chicken-plate body armor atop that, plus a survival vest and radio. “Eight and a half hours and I never got out to pee,” he says.

In Desert Storm, the Cobra shared the sky with the helicopter that would replace it: the Hughes AH-64 Apache. Werner’s first impressions of the technology-chocked helo are mixed. “The Apache’s an awesome helicopter—if everything works,” he says. He also notes that in Desert Storm, Cobras destroyed more vehicles than Apaches did: “And we did it with fewer aircraft and less support.”

When all units converted to Apaches, Werner drew the assignment to fly the very last Army Cobra out of Europe. Crossing the English Channel, he detoured to wing over the white cliffs of Dover. “Surreal and also kind of melancholy,” he says. “If the Army still had Cobras, I’d still be in. It’s the sexiest thing ever made.” Today, he pilots a Eurocopter EC120 for the Baltimore Police Department.

Between 1967 and 1973, Bell manufactured more than 1,100 AH-1s. The Cobras logged more than a million flight hours in Vietnam; 270 of them were destroyed, and 231 Cobra pilots died in combat or went missing. In 1999, the Army retired the AH-1 from active duty. Twin-engine AH-1 SuperCobra variants are still in use by the Marine Corps.

Mike Folse left Bell Helicopter in 1971. “I still get feedback,” he says. “I get emails—two or three a week. People who went to Vietnam tell me, ‘If it hadn’t been for the Cobra, I’d be dead.’ ”

Coming in the next issue: “Snakes and Loaches,” the Cobra’s exploits in Vietnam.