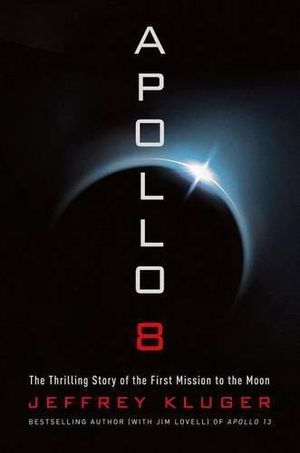

Apollo 8: A Journey Into Deep Waters

The thrilling story of the first mission to the moon.

:focal(553x373:554x374)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/72/b7/72b7f04c-f29a-4fd7-a319-988d63e9ff27/s68-50265-large.jpg)

In his new book, Apollo 8: The Thrilling Story of the First Mission to the Moon, Time magazine senior editor Jeffrey Kluger explains how NASA crafted the risky mission in just four months. The author drew from interviews with astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders. Kluger spoke with senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in June.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Kluger: A better question would be why I waited so long to write it. Apollo 13 was my first book, and it was a good story for a first-time author. The narrative, precisely as it played out in real life, was a ripping good tale of danger and survival and human ingenuity. It would have been hard for even a novice to mess it up.

Apollo 8 was a very different story to tell because it was basically a mission in which every single little thing went right. The drama, however, was in both the context of the year and the transformation the mission wrought on the species as a whole. The flight took place at the very end of 1968—one of the grimmest, bloodiest passages in human history. There ought to have been nothing that could redeem a year like that one, but Apollo 8 did. The mission’s power was not just in the daring it took to plan such a journey—only 16 weeks elapsed between the decision to go and the moment Apollo 8 lifted off—but in the perspective it gave us on our own planet. Over the course of that one week—Christmas week, no less—we went from being a species of one world to a species of two. Nothing would ever be completely the same again.

What did you discover about the mission that wasn’t widely known before?

A lot of it involved what went on in those 16 weeks. It was no surprise that I would have a lot of fun writing the scenes in the spacecraft and Mission Control after the mission began. Those were the two places the adventure was unfolding. But it was in the administrative offices of NASA—at Canaveral as well as in Houston, Washington, and Huntsville—that the idea was dreamed up and that again and again, administrator after administrator, heard the plan, pronounced it ridiculous, and then inevitably fell for its daft brilliance.

There was an almost incalculable amount of work they had to do to get the hardware, software, and personnel ready to make the trip in the four months they had, but the first big hurdle was simply deciding that the riskiest, scariest, and boldest move was also the right move. That was the least told part of the story up until now, and one I enjoyed exploring. As an aside, I also loved reading through the transcripts of the private cockpit conversations among the astronauts themselves and learning what they were thinking, saying, and doing as they approached, orbited, and left the moon. I included a lot of that in the book.

Apollo 11 gets a lot of glory—rightly so. But do you think Apollo 8 is somewhat under-appreciated?

I do think Apollo 8 is underappreciated because, again, it was the first time we sailed across the deep waters of deep space and visited an entirely different world. Flying in Earth orbit—while a magnificent accomplishment—is still a little like dog-paddling in your home harbor. The first trip to the moon was a whole different enterprise. Apollo 11 was actually the third time astronauts visited the moon (Apollo 10 orbited too), even if it was the first time they got their boots dirty.

In the wake of the Apollo 1 launch-pad fire, how risky was Apollo 8?

The people inside NASA always operated on a sort of knife-edge between avoiding and courting risk. You can’t do something as innately dangerous as flying in space without accepting the likelihood that you might lose crews in the process, but every single decision you make has got to be animated by controlling that risk as much as you can. Had the Apollo 13 crew lost their lives in space, the tragedy would have been somehow easier to take because by then the Apollo spacecraft was a proven machine. The explosion that crippled it was the result of a cascade of improbable problems, any one of which was unlikely, and a whole string of which were all-but impossible to occur. When the impossible did occur, NASA could at least be confident that while there had been errors along the way that led to it, no one had been grossly negligent.

The Apollo 1 fire, on the other hand, was equal parts tragedy and disgrace. That first iteration of the spacecraft was a jalopy, and everyone knew it, but the press of the space race made people overlook the problems. After the death of the crew, NASA vowed never to be so careless or cocky again. It took a lot to push them past that wariness, and a brainstorm mission like Apollo 8 was it.

Based on your interviews with Borman, Anders, and Lovell, what were the most memorable moments of the mission for them?

Borman has always been very clear that the moon meant little to him; it was the Earth—viewed from the remove of a quarter of a million miles—that really changed him. He was a quietly religious man then and remains so today, and I think the sight of the home planet resonated deeply with his faith.

In Lovell’s case, I think the whole wild ride of the mission was what lingers most after all these years. I say in the book that he was never so happy as when he was in space and never so happy in space as when he was doing something new and outrageous, and Apollo 8 was decidedly that.

Anders was very much an engineer and a man of science. I think the sublime pleasure of flying so remarkable a spacecraft may have been his greatest thrill. He had also trained himself to be a sort of lay geologist and cartographer, and he took very seriously his job of compiling the first up-close photographic atlas of the moon. Not for nothing, he also took the celebrated Earthrise picture.

Who were these astronauts?

All three of these guys are—and were—heroes first to last. If that sounds sentimental, well, than call me sentimental. But they are all driven by a sense of personal mission, and service to country and humanity was a big part of that. No one went to space to get rich. They all went there for a larger good.