We Fly the Last Electra Juniors

Seven remarkable Lockheed Model 12s showed up (late) for their diamond jubilee.

:focal(728x385:729x386)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/55/a155d38c-b28c-4b57-a923-d36cc082c3c8/electras_at_airventure.jpeg)

Don’t blame age for making a group of Lockheed Model 12 Electra Juniors late for their own 75th anniversary celebration. The sleek, twin-engine transport can still cruise at 175 mph. In 2014, seven of the world’s 10 then-airworthy Juniors rendezvoused in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, during the Experimental Aircraft Association annual AirVenture fly-in—a mere three years late for the model’s diamond jubilee. It’s remarkable the gathering occurred at all, says Peter Ramm, who coordinated the event, considering the scheduling and logistical challenges, and given that L-12 owners are “a pretty independent bunch.”

Standing wingtip to wingtip outside the Red Barn, EAA’s vintage aircraft headquarters, this may have been the largest collection of the type ever assembled.

“I don’t know any time there were seven parked together, even at the factory,” said Les Whittlesey, who flew his L-12 to Wisconsin from Coto de Caza, California, just down the road from Burbank, where Electra Juniors were built.

Aimed at small airlines and the corporate transport market, the Lockheed 12 Electra Junior was the six-passenger version of the 10-passenger Lockheed 10, famed as the airplane Amelia Earhart was flying when she went missing. The impetus for the Junior’s development was in part a Bureau of Air Commerce design competition aimed at promoting aircraft for feeder airlines—carriers that transport, or “feed,” travelers to hub airports from destinations not served by larger lines. Powered by Pratt & Whitney R-985 Wasp Junior SB radial engines, the L-12 first flew on June 27, 1936, three days before the competition ended. Lockheed won the contest by default; the two other entrants, the Beech 18 and the Barkley-Grow T8P-1, failed to fly before the deadline.

Available in both airline and executive interior configurations, the L-12 featured innovations such as a fire suppression system in the engines, an emergency exit, and a fuel dump system, which was rare at the time.

But despite its advanced design and incentives provided by the government, the L-12 garnered few orders from airlines.

“The reality is, during that time a 15- to 18-passenger airliner would work well as a feeder, and the fixed costs of crew, fuel, oil, and airframe really wouldn’t be too much more than the skimpy six-passenger Lockheed speedster,” said H.G. Frautschy, former executive director of the EAA’s Vintage Aircraft Association.

Many of the L-12s at the reunion were first owned by oil companies; with their big balloon tires, a stall speed of about 65 mph, and conventional gear configuration, they could easily operate on unimproved airstrips in oil fields. Between 126 and 130 Juniors were built; production ended in 1941.

During World War II, many L-12s were requisitioned by U.S. and British military services. Sold as surplus after the war, most were operated as corporate aircraft into the 1960s. As companies transitioned to more contemporary twin-engine business turboprops and jets, L-12s began finding their way into private hands, still being flown rather than displayed as artifacts. The current owners, all vintage aircraft devotees, began acquiring them in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Despite a lack of market impact or historic significance, the L-12 does have claims to fame. An L-12, equipped with cameras, flown by Australian inventor and photography pioneer Sidney Cotton served as a spyplane before World War II, gathering important intelligence on German military positions.

And the aircraft’s cameo, in Air France livery, as the airliner awaiting Ingrid Bergman in the closing scene of the movie Casablanca adds to the L-12’s cachet.

The Junior was among the first aircraft designer Kelly Johnson worked on at Lockheed Aircraft. (Prior to joining the company, Johnson had advised Lockheed to put an H-tail on the L-10 for improved stability, following wind tunnel tests at the University of Michigan, where he was then a student assistant.)

“Kelly Johnson actually wrote our flight manual—his name is prominently placed on the front cover,” said Uwanna Perras, who, with his brother Yon, meticulously restored their 1940 Junior, regarded as the queen of today’s fleet.

The L-12’s slim flight manual is itself a study in streamlining, if not minimalism, excluding, among other items, weight and balance data. Johnson simply noted that whatever combination of passengers and fuel the airplane was carrying, as long as the forward and rear baggage compartments were not overloaded, the center of gravity wouldn’t exceed the forward or rear limits.

Whatever Johnson’s involvement in the Junior’s development, he apparently left it off his career highlights reel. “Kelly Johnson was my boss when I was a new hire at Lockheed almost 60 years ago,” John Underwood wrote in an email. “He seemed to be most proud of the L-14 [Super Electra], L-18 [Lodestar], and [L-049] Connie in the civilian category.”

To the Junior’s owners, the graceful lines and perfectly proportioned airframe are the type’s chief attractions. “The Lockheed 12 is probably the greatest example of that beautiful, classic Art Deco era of aviation,” said David Marco of Atlantic Beach, Florida, owner of a completely restored 1938 model. “It epitomizes that time more than any other airplane.” Patrick Donovan of Bellingham, Washington, declares: “It’s the prettiest airplane ever built,” and many vintage aircraft aficionados seem to agree. Among other awards, four of these seven L-12s (Ramm’s, Marco’s, Whittlesey’s, and the Perras brothers’) previously won the coveted Gold Lindy at Oshkosh for best antique aircraft, and Joseph Shepherd’s earned Antique Outstanding Transport honors, a tribute to the type’s inherent appeal as well as the quality of the restorations.

But some fans view the aircraft in a less romantic light. “It’s quite a marvel, but it’s hard to believe they would design an airplane like that,” said vintage aircraft expert and pilot Kirk McQuown of Redondo Beach, California, who headed the restorations of two of the Lindy-winning L-12s. He cited such quirks as the prone-to-fail landing gear, an over-complex fuel system, and a flap connection that can send the aircraft into a snap roll in the event the flap fails. “You’ve got to sit down with somebody and say, ‘This is not a normal airplane’ ” before that person attempts to restore or fly the L-12, McQuown said.

All the L-12 owners at the reunion knew one another, though they hadn’t all met face to face. The gathering gave them a chance to tour the fleet together, crowding into each L-12 in turn. “We all did them a little bit different,” said Shepherd, “but they all basically have the same original interior, just like they came in the ’30s.”

The owners also discussed L-12 operational and maintenance issues onstage at a Lockheed forum, collectively held their breaths when a freak hailstorm darkened the sky one afternoon, and took to the skies for group air-to-air photos. They feel a connection from their common mission. “We all know we’re just caretakers,” said Donovan. “Everybody’s trying to be true to the history, and pass these on to the next generation.”

The Movie Star

Year built: 1936. Owner: Joseph Shepherd, Fayetteville, Georgia.

After flying B-18s as a freight dog after college, Joseph Shepherd was a rabid Twin Beech fan—until he flew a friend’s L-12 in the 1980s. “The Lockheed is light-years ahead of the B-18 in every way,” he says. “I just fell in love with the Lockheed and hoped one day I could find one.” The son of a World War II fighter pilot and father of a 747 captain, Shepherd affirms aviation is “in the family.” In 1988 he traded a Cessna 195 for an L-12 that had been sitting in a field for almost a decade. (The owner had two Juniors; the Perras brothers bought the other.) “The more we probed and inspected, it was determined it needed a complete rebuild,” Shepherd says. The project consumed 20,000 hours over 17 years. “I elected to go with modern avionics,” Shepherd says of the do-over. “Where I live [near heavy airport traffic], you have to be aware of where you are.” But the airplane is true enough to the period to have earned a role in the 2009 film Amelia as Earhart’s L-10 and, more recently, a spot in 42, the 2013 film about baseball great Jackie Robinson. The airplane also won an Antique Outstanding Transport award at Oshkosh in 2007, along with a host of other honors.

Powered by a Wasp

Year built: 1938. Owner: David Marco, Atlantic Beach, Florida.

“I wanted a classic 985 twin,” says David Marco, referring to Pratt & Whitney’s R-985 Wasp Junior radial engine. He bought his L-12 while visiting aircraft preservationist Kermit Weeks at the Fantasy of Flight Museum in Florida. “I was fishing in Weeks’ lake and closed the deal in a kayak,” Marco says. “We spent more than 10,000 hours putting it back exactly the way [it was when] it rolled out of the Burbank factory for Phillips Petroleum when they picked it up in March ’38.” Kirk McQuown headed the restoration, performed at Chino Airport. “The leather has to be oiled every month,” Marco says. “It’s a stunning exterior and interior, but not exactly the everyday airplane I wanted it to be.” The son of a World War II B-24 pilot who built a thriving business “just so he could have bigger and better airplanes,” Marco is following his father’s lead. His collection includes a P-51 Mustang, T-34 Mentor, de Havilland Beaver, and Citation CJ2, but the Gold Lindy Junior remains the pride of his fleet. “Even by today’s standards, it’s pretty darn amazing,” he says. He’s thinking of building an air conditioned hangar for it; “I just haven’t figured out how to break this news to the others yet,” he says.

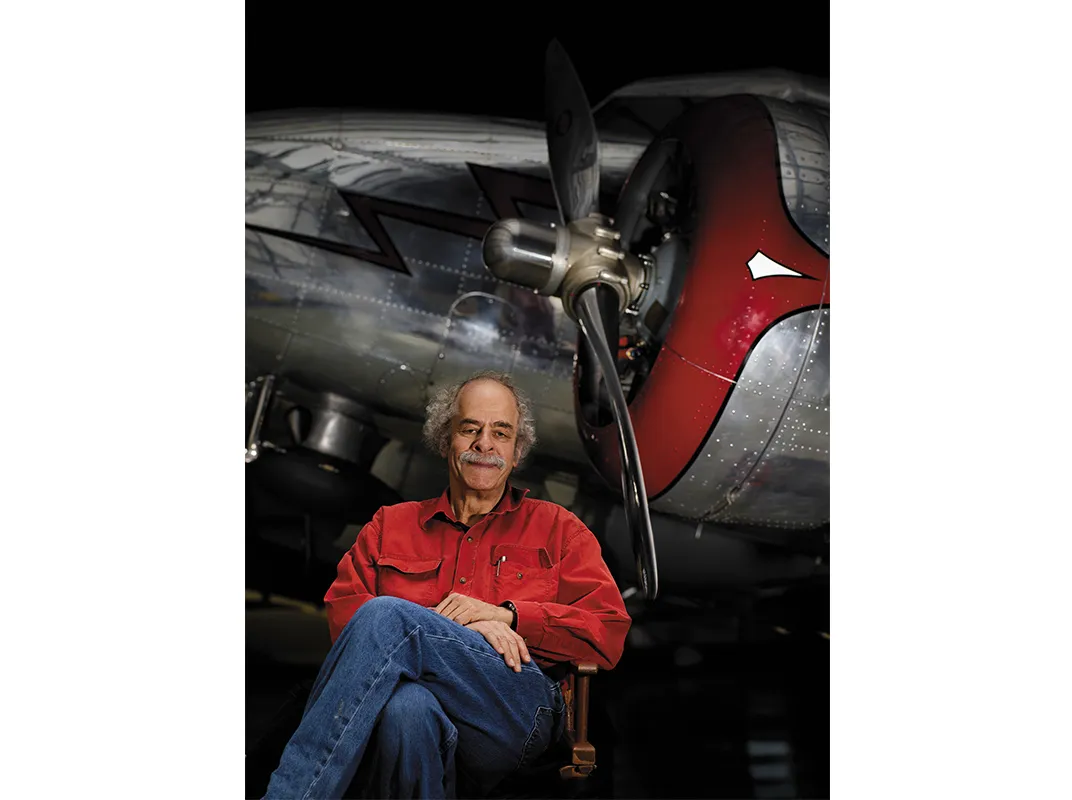

The Ringleader

Year built: 1937. Owner: Peter Ramm, St. Catherines, Ontario, Canada.

“The Lockheed is such a pleasure to be in and fly that getting anywhere is completely beside the point,” says retired neurobiologist Peter Ramm. “It’s ideal for someone like me; I don’t want to get anywhere.” Ramm, the son of a bomber pilot, started flying gliders in grad school (“It de-stressed me”) and transitioned to powered aircraft in the late 1990s after leaving a career in research and founding a successful biotechnology company. His 1937 L-12 was originally owned by Varney Air Transport, predecessor of Continental Airlines, “so this is one of the first two airplanes that Continental ran,” he says. By the time Ramm bought it in 2007 it was “flying but shouldn’t.” It next flew in 2012, following a complete restoration, and won a Gold Lindy at AirVenture that year. Though he claims to be “a bit of a hermit,” Ramm spearheaded the L-12 gathering (“I did send out some emails and suggest it would be fun to do,” he admits). Today his airplane appears at regional fly-ins, provides rides to winning bidders at charity fundraisers, and carries Ramm on the occasional trip. Ramm is now 69, and the aircraft is for sale. “I love it dearly,” he says, “and am in no rush to sell.”

The Queen of the Fleet

Year built: 1940. Owners: Uwanna Perras and Yon Perras, Morrisville, Vermont.

In the 1980s, Vermont natives Uwanna and Yon Perras were living in Hayward, California, working for the Air National Guard and Sandia National Laboratories, respectively, and flying a Beech Staggerwing they’d restored. A friend suggested they check out the 12, “even though you’re Beech people.” The brothers found a Junior in Texas in 1988 and planned to “leave it in the rough,” Uwanna says. “[But] you start looking at things: ‘Oh, we’ve got to fix that,’ and ‘Oh, we need to wire that.’ First thing you know, it was completely disassembled.” The restoration took 10 years and more than 20,000 hours of labor, almost all performed by the brothers themselves. (Interior work was sewn by Giatto’s Interiors in San Jose, California, while the Perras brothers did the installation.) The 1999 Gold Lindy Antique winner, theirs is the restoration against which owners judge the rest of the fleet. It’s “virtually brand new; we fabricated everything,” Yon says, including the mold they built to forge new engine cowls. The brothers, now retired, have moved back to Vermont and keep the Lockheed on the family’s former dairy farm, which has an airstrip. They flew the L-12 to last year’s AirVenture and to the Triple Tree Aerodrome Fly-in in South Carolina.

The Flying Dentist

Year built: 1940. Owner: John O’Keefe, Winthrop, Washington.

Most L-12 owners are the children of aviators, born with avgas in their blood. Not John O’Keefe. “I’m a dentist,” he says. “I never envisioned myself owning a Lockheed.” He learned to fly in his late 30s and “jumped right into the old taildraggers,” soon buying a Beech Staggerwing and then a Spartan Executive. “I just always appreciated the Deco airplanes of the ’30s and early ’40s.” His 1940 L-12, purchased in 2001, was first owned by the Humble Oil and Refining Company. “You can still see where they almost gouged the aluminum when they were putting the logo on,” O’Keefe says. “After polishing the airplane enough times, you know where it is.” His Junior was in “fairly good shape” when he bought it, but still required firewall-forward engine overhauls, all new control cables, and landing gear restoration. “Just safety stuff, not so much cosmetic,” he says. Based at Methow Valley State Airport in Winthrop, Washington, O’Keefe’s Junior appears at local fly-ins, and he uses it “real recreationally,” leaving family transportation missions to his cheaper-to-operate Spartan or amphibious Maule.

Combat Veteran

Year built: 1938. Owner: Les Whittlesey, Coto de Caza, California.

The son of an ex-Air Force pilot and airline captain, Les Whittlesey grew up in Torrance, California, surrounded by vintage aircraft and restoration activity. In 2002 he was looking for a twin-engine aircraft to complement his Cabin Waco when a freshly annualed L-12 appeared in Trade-A-Plane. “I promised my wife it wasn’t another project,” says Whittlesey, a real estate developer. Once owned by transport magnate E.L. Cord, the aircraft served in the Royal Air Force during World War II, taking fire “from our own side over Belgium—you can see the patch on the wing.”

Even though the Junior wasn’t as airworthy as advertised, and assurances to his wife notwithstanding, Whittlesey bought it. Six restorers (“more artisans than mechanics”) worked full time for three years rebuilding the airplane, while Whittlesey “traveled throughout the United States to look at other Lockheeds” for inspiration and restoration guidance. The Gold Lindy-winning Grand Dame, as it’s called, is based at Cal Aero Aviation Country Club at Chino Airport, and Whittlesey uses it for family and business travel, as well as for display and charitable missions. “It’s a good cross-country airplane,” he says. “I usually don’t have to pay ramp fees; they let me park it for free because it’s so unique.”

The World Traveler

Year built: 1938. Owner: Patrick Donovan, Seattle, Washington.

Patrick Donovan, a third generation pilot, recalls his first sight of an L-12, at Arlington Municipal Airport in Texas in the 1970s. “The sun was going down,” the retired airline captain remembers, “and it dropped below a low cloud layer and shined on one parked on the ramp. I said, ‘I’m going to grow up and get one of these things.’ ” Originally owned by Continental Oil Company (today’s Conoco), Donovan’s Lockheed “was a barn find,” bought for $10,000 in 1989. Flying it back to Seattle, he “trailed parts and oil across the United States.” He has since reskinned most of the fuselage, rebuilt the landing gear, hung new engines, and restored the interior down to the Bakelite knobs on the Deco ashtrays, and he is still not finished. The aircraft made a round trip to New Zealand, where Donovan resided for several years, and this year flew to England and back, some 9,000 miles. Now based at Washington’s Columbia Pacific Aviation, the Junior transports Donovan to airshow engagements and charity flights. “It creates a small riot every place you go, it’s enormously fun to fly, and you can pile all your buddies in and use it,” he says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/16/4d/164d4456-c1ef-4cbb-bb21-2be9939d1870/electra-3.jpg)