Cameramen in Vietnam

How Air Force photographers created a visual record of the war in Southeast Asia.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/df/d1/dfd12584-88b9-42d3-b11a-03f27c56d368/03h_jj2017_kenhackmanguarddogchoppera_live.jpg)

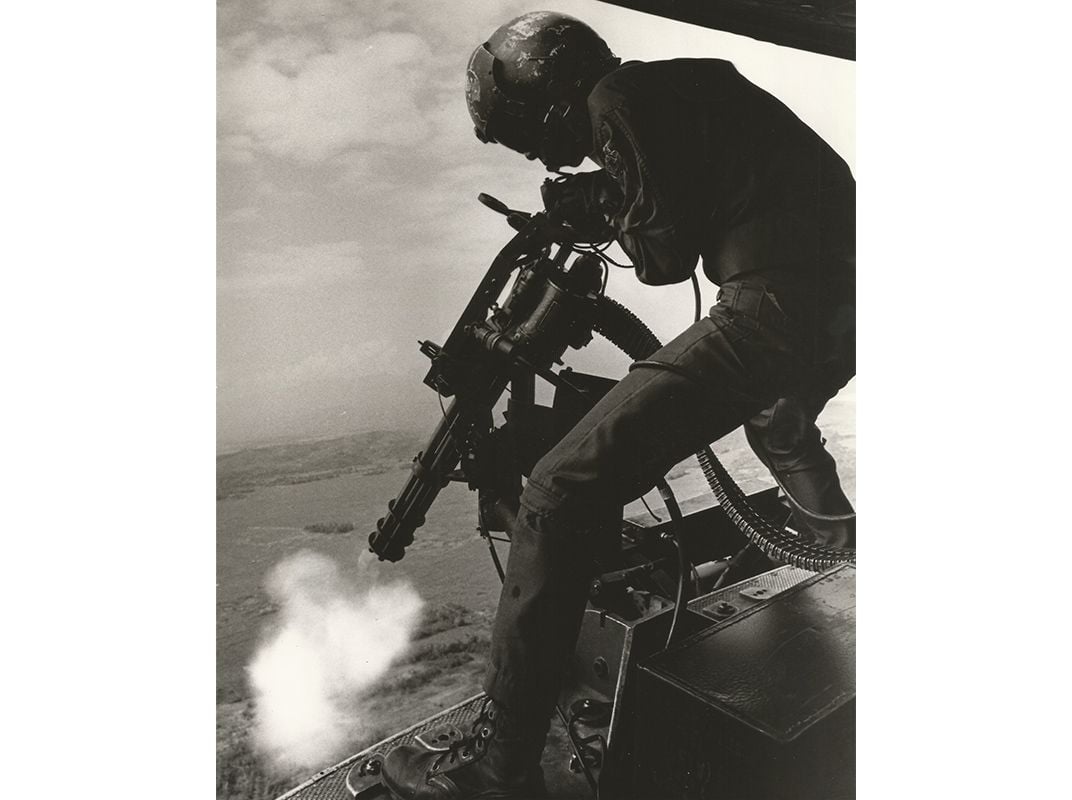

They called themselves “shooters,” though the only thing they ever shot was film. For U.S. Air Force combat cameramen who served in Vietnam, memories of the war never fade; they are frozen in the thousands of images the photographers captured there.

Their assignment was ambitious, even daunting: record for posterity and actionable intelligence the Air Force’s participation in the fight. The mission didn’t start off well. Michael R. Potochick can attest to that.

A fledgling first lieutenant in 1964, Potochick was happily serving as a “motion picture officer,” frequenting Hollywood studios and overseeing the production of Air Force training films, when he received a new title: commander of all Air Force photographers in Southeast Asia. With little more than a skeleton crew, he was ordered to document what was rapidly becoming a full-blown war. Potochick had never supervised enlisted personnel. He’d never done aerial photography. He’d never even worn combat fatigues. “I was very ill-prepared,” he says.

He commanded photographers, motion picture camera operators, and film technicians—about 20 men at Tan Son Nhut Air Base, outside Saigon. Everyone, including Potochick, was required to fly combat missions. They also were responsible for maintaining the camera pods on strike aircraft, used to record bomb and missile attacks. Pilots didn’t like him because the pods increased drag, slowing the airplanes and burning fuel. Air Force intelligence officers disliked him because it took so long to process the film from the pods.

“By the time we’d get them back their pictures, it could be weeks,” Potochick says. “By then, they’d have forgotten the mission. It was very frustrating.”

And the work was dangerous. Potochick and three of his men were wounded in a grenade attack in Saigon. During his one-year tour of duty, he was exposed to the toxic herbicide Agent Orange while photographing defoliation missions on “Patches,” a C-123K Provider transport famous for having sustained nearly 600 hits from enemy ground fire. (The airplane is on display today at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio.)

In February 1966, four months after Potochick returned Stateside, the Air Force activated the 600th Photo Squadron, tasking it with providing all Air Force photographic services in Southeast Asia except reconnaissance. The unit would eventually grow to include more than 550 personnel scattered across 16 detachments in South Vietnam and Thailand.

The squadron’s first commander, Colonel James P. Warndorf, told Air Force debriefers in 1967 that he had been under constant pressure to speed the processing of still pictures and combat footage. Warndorf quoted one wing commander as lecturing him, “Your goal should be showing my pilots the film of their last mission before they fly their next one.”

Two T-39 Sabreliners remained on standby to whisk exposed rolls from outlying airfields to larger bases, where Air Force photo labs operated around the clock. During January and February 1967, the squadron developed 630,000 feet of film. Such output required technicians to work 12-hour days with no days off, often for three and four months straight. A few men cracked under the strain and had to be hospitalized, according to Warndorf. At least one committed suicide.

Eleven months before the last U.S. troops were withdrawn from Vietnam, in March 1973, the 600th Photo Squadron was inactivated. Today, nearly 800 airmen, soldiers, sailors, and Marines, attached to many active and reserve squadrons, serve in what is collectively known as Combat Camera.

**********

The first time Air Force Chief Master Sergeant Douglas W. Morrell had to parachute from a burning airplane was in World War II, when he was filming a bombing run over Romania. For 25 days, he evaded capture, hiking across Yugoslavia and Albania before using his .45-caliber pistol and $100 in gold certificates to persuade a fisherman to take him to Allied-occupied Italy. Two months later, Morrell’s B-24 was hit by Luftwaffe fighters over the oilfields of Ploesti. Again, he managed to get out, seconds before the Liberator exploded. Five other crew members were not so lucky. Morrell ended up in a German prison camp; he lost 60 pounds in captivity.

“Pretty good way to go on a diet,” he jokes today.

At 98, Morrell is widely regarded as the patron saint of military videographers. Those who credit him with practically inventing the art of combat storytelling through film know him simply as The Legend. “Story’s the only thing,” says Morrell. “It will always be important.”

“Doug Morrell gave real meaning to what it meant to be Combat Camera…to capture history and to have the courage and sacrifice to risk it all for the imagery,” says Air Force Chief Master Sergeant Timothy R. Bailey, who, as a young airman, considered himself fortunate to meet The Legend.

On his first combat mission in Vietnam—on February 28, 1969, just shy of his 50th birthday—Morrell was filming a sensor drop over the Ho Chi Minh Trail when 57mm machine-gun fire tagged his O-2 Skymaster. The observation plane’s left wing erupted in flames, dangerously close to a rocket pod. The pilot ordered him to bail out. Morrell didn’t have to be told twice.

“I had my eyes closed because all I could see were these big ol’ propellers spinning,” he says. “How one of them didn’t get me, I have no idea.”

He hit a tree on the way down, fracturing his heel. Hiding out for nine hours before being rescued by helicopter, Morrell used his survival radio to direct fighter attacks on the anti-aircraft battery that had shot his airplane out of the sky. His efforts would earn him a Bronze Star for valor. His pilot, unfortunately, was captured and spent four years as a POW.

Morell laments that he has no film to chronicle that day; he lost his photography equipment when he leapt from the stricken Birddog.

“The Air Force didn’t court-martial me,” he says with a chuckle from his home in Highland, California, where he’s lived since 1969. “But they didn’t promote me either.”

**********

Pete Seel grew up around aviation. His father received a Distinguished Flying Cross while flying B-25 Mitchell bombers in World War II; after the war, he flew small aircraft. So it was hardly a stretch when Seel joined the Air Force at the height of the Vietnam conflict.

He’d been studying architecture at Washington University in St. Louis, but after three semesters decided that his life had become “too rote and organized.” While in college, he’d bought a camera to snap pictures of his architectural models. The Air Force recognized his talents and made him a photographer. For two years, he was assigned to the photo lab at Lowry Air Force Base in Denver before volunteering for an 18-month combat tour.

“I saw it as a grand adventure,” says Seel, 68, today a journalism professor at Colorado State University in Fort Collins. “People thought I was crazy.”

The Air Force sent him for escape-and-evasion training in Washington state for a week, then to the Philippines for another week of jungle survival school, before posting him to the 600th Photo Squadron at Tan Son Nhut in April 1970.

As long as he came back with good photos and a story to tell, Seel soon discovered, he was allowed to travel virtually anywhere he could bum a ride. With his Air Force-issued Nikons, he chronicled helicopter-borne South Vietnamese infantrymen jumping into hot landing zones. He covered the secret invasion of Cambodia. He landed at the Marine base at Khe Sanh to photograph Air Force ground personnel tasked with keeping the runway repaired amid mortar fire. Vietnam’s monsoonal weather proved nearly as formidable an adversary as the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese. “It was like dumping a bathtub on your head every day for six months,” Seel says. Within two months, the lenses of his cameras were getting clogged with fungi.

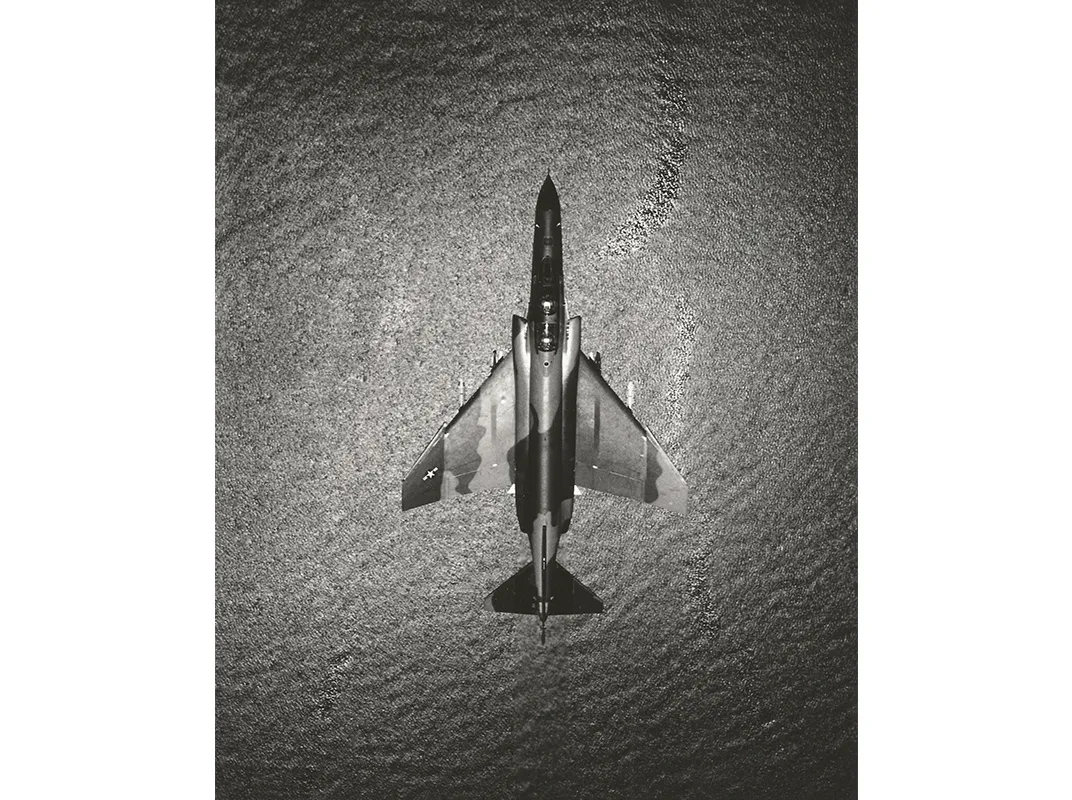

In all, Seel logged 70 combat missions, including several in F-4 Phantoms. It was on one such flight, in July 1971, that he made one of his favorite photos.

After bombing North Vietnamese army trucks along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the F-4 was descending over the South China Sea toward Da Nang when the pilot asked Seel if he wanted to photograph another F-4 flying below them. The pilot promptly rolled their Phantom on its back. Hanging upside down from the straps of his ejection seat, Seel raised his arms, pressed his camera lens against the top of the jet’s canopy to avoid vibration, and captured what can only be described as a work of art.

**********

The year was 1966, the air war in Southeast Asia was ramping up, and Air Force brass were not happy. As far as they were concerned, their photographers were doing a lousy job showing the folks back home what the fighting was really like. Enter Ken Hackman.

Following a stint as an enlisted man, Hackman had gone to work for the Air Force in 1960 as a civilian photographer based at the Lookout Mountain Air Force Station in Los Angeles, where his duties included photographing atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons in the western Pacific. What was happening in Vietnam would soon take precedent.

“The color photography coming out of there was pretty awful,” Hackman, 79, says. “Much of it was stupid stuff—the mess hall at Nha Trang, the O-club, the dorms. The Pentagon was riding my boss, so he asked me if I’d go over there to make some pictures. I said okay.”

For two months, Hackman wandered around the war zone, hitching rides on combat aircraft and shooting rolls of Kodachrome.

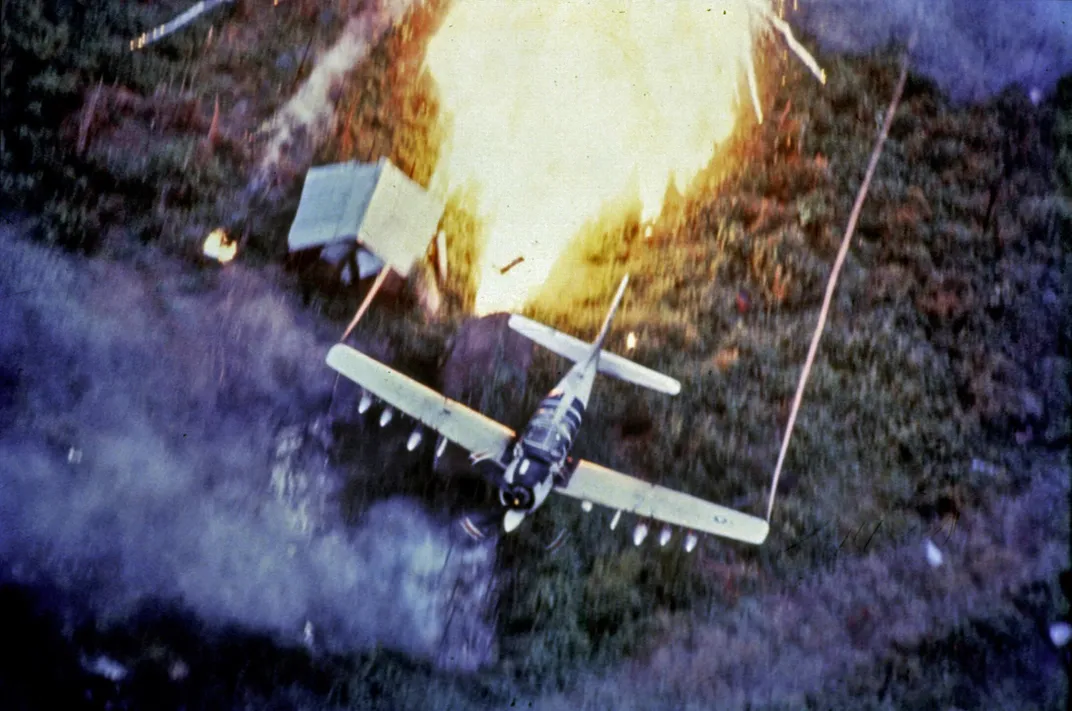

At Pleiku, he had the idea to photograph a low-level napalm drop on an enemy position. The question was: How best to make the shot? An A-1E Skyraider pilot suggested cutting in front of his wingman at the moment of impact, affording Hackman the perfect vantage point from the rear seat. “Just don’t get me killed,” Hackman recalls telling the Spad jockey.

He got his shot and lived to tell the tale.

Hackman returned to Vietnam six years later to make more pictures. Many of his photographs, along with thousands of others shot by Air Force combat cameramen, can be found today in the National Archives.

**********

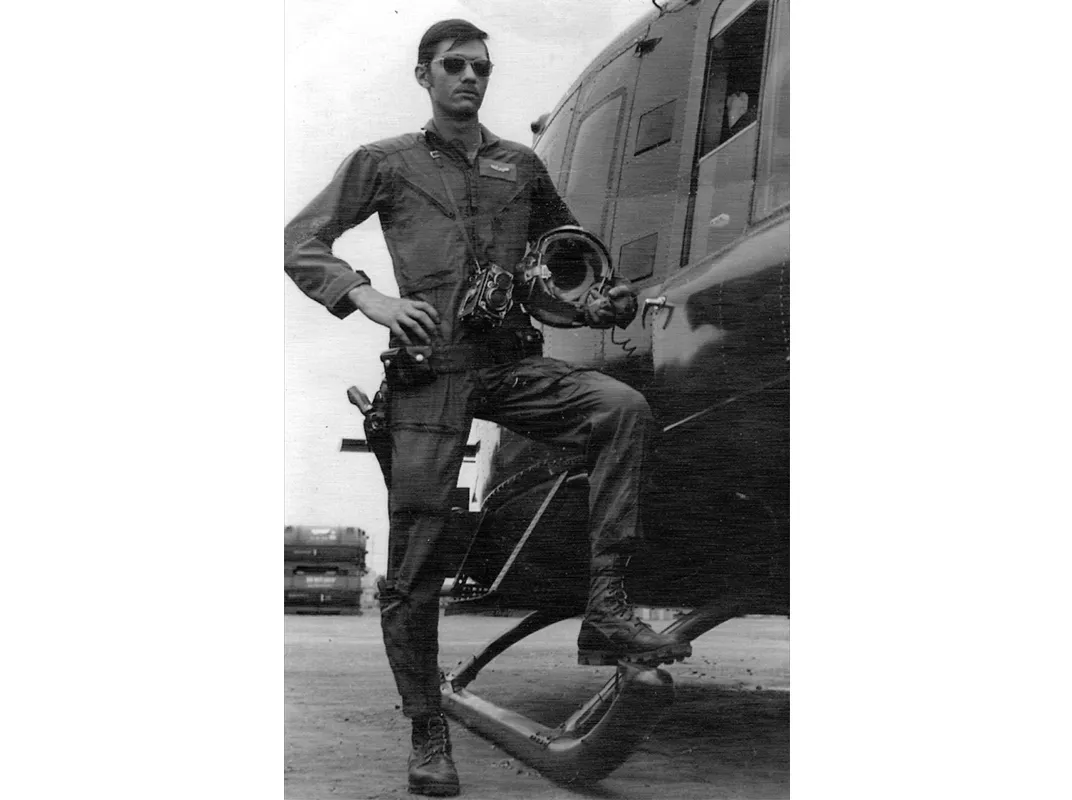

There he stands on the flightline at Tan Son Nhut in his flightsuit and aviator shades, a .38 Special holstered to his hip, a Rolleiflex hanging from his neck, one foot propped on the skid of a Huey, looking every inch the combat cameraman.

“Everybody had that ‘Clint Eastwood’ shot taken,” says Michael Felitti, 66, a commercial printer living in Tampa, Florida. “It was a big joke.”

Dressing the part of the warrior was one thing. Living a warrior’s life was another. Aside from occasional mortar or rocket barrages, the hardships Air Force shooters like Felitti endured bore little resemblance to those that Army and Marine grunts in the field faced daily. When photographers weren’t on an assignment, which usually didn’t last more than a few days, they dined in mess halls and slept in air-conditioned barracks, cloistered within the confines of heavily defended bases.

Felitti logged 25 missions in Vietnam—enough to earn two Air Medals—but by his own account, much of his time was spent on the ground, shooting assignments that were hardly worth writing home about. Among myriad other responsibilities, Air Force combat cameramen photographed fender-benders on base, shot promotion ceremonies, documented aircraft accidents, and took close-ups of failed aircraft parts. There were also the dreaded “grip-and-grins”: high-ranking officers and visiting dignitaries shaking hands, photographed for public relations purposes. Still, regardless of their distance from the actual fighting, the routine didn’t exclude Felitti and his fellow shooters from the ever-present risk that came with merely being in a war zone.

In November 1970, Felitti was scheduled to fly from Tan Son Nhut to Nha Trang on a transport loaded with more than 70 South Vietnamese troops. Another photographer new to the squadron and anxious to get some time in the field, Airman First Class Frederick R. Neef, insisted on going instead. “I remember like it was yesterday,” Felitti says, “arguing with him.”

Neef won the argument. Nine days later, his body was found on a remote hillside. Poor weather was blamed for the crash; everyone on the aircraft had died. Neef was one of at least 11 members of the 600th Photo Squadron to have died in Vietnam.

**********

After enlisting and taking an Air Force aptitude test, it was decided that John Engle would make the perfect linguist. The plan, he says, was to send him to an Ivy League school where he would learn Spanish. The only problem was that when Engle’s basic training ended, Harvard was between semesters, and the Air Force wasn’t about to pay him to sit around, waiting for classes to start up again. So they made him a motion picture cameraman.

By most estimates, slightly fewer than half of Air Force combat cameramen in Southeast Asia produced movie footage rather than still pictures. Over an eight-week training course, photographers learned composition and camera angles, how to frame a scene, and, in the case of motion picture operators, how to shoot subjects using multiple focal lengths to give their film editors various perspectives to be creative with. For Engle, a small-town boy from eastern Kentucky, it was exhilarating.

He was sent to Colorado Springs to document construction of the new NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense) combat operations center inside Cheyenne Mountain, and to Green River, Utah, to film missile launches, then to Nevada to document underground nuclear tests. Within a year, he was shooting movies out of Bien Hoa Air Base, northeast of Saigon.

When Engle first arrived, there were more photographers than there were extra seats on combat aircraft. He was left to chronicle the sweaty, back-breaking work of ground crewmen who loaded ordnance onto combat aircraft. He filmed U.S. military doctors and dentists treating Vietnamese patients: “Winning hearts and minds—all that stuff.”

But after one of his squadron mates, Airman First Class Darryl G. Winters, was shot down in July 1966, becoming the first Air Force combat cameraman killed in action in Vietnam, Engle was soon using his 16mm Canon Scoopic to film bomb drops from the back seat of a F-100 Super Sabre. The Air Force would later send him out with Army ground forces attacking communist forces in Vietnam’s notorious Iron Triangle. One morning, Engle says he awoke to learn that an enemy mortar round had slammed into an ammunition dump near where he’d been sleeping. He’d been so exhausted, he didn’t wake up. Luckily, the shell failed to explode.

A radio announcer and former high school English teacher who lives in the same town in Kentucky where he grew up, Engle, 71, says he occasionally sees Vietnam combat footage on TV. He wonders if some of it is his.

**********

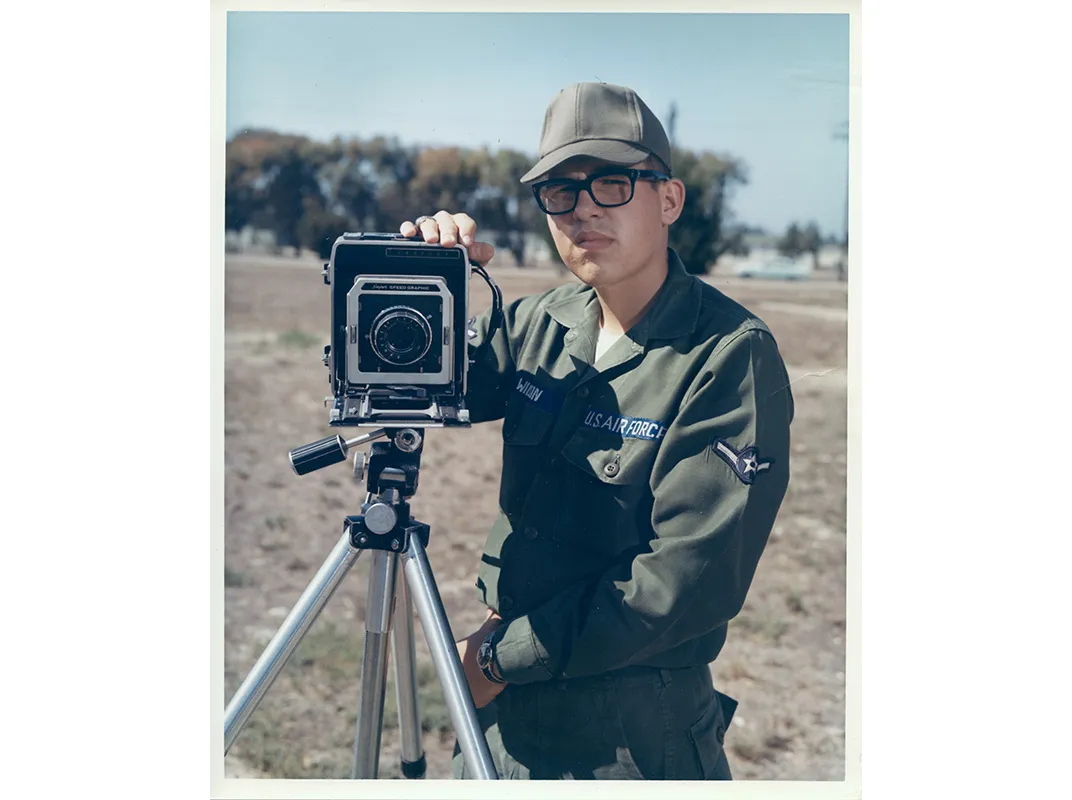

Steven A. Wilson may not have been born a photographer, but it didn’t take him long to become one. When he was 10, his father gave him a 35-millimeter camera he’d bought for $6 from some guy who’d won it in a contest.

“I shot everything,” Wilson says, “family trips, the kids next door, neighbors. In high school, I shot wallet-size pictures of the majorettes. They cost me 13 cents to make. I was selling them for 50 cents. The principal called me in and made me yearbook photographer.”

By 19, he was serving as a combat cameraman with the Air Force’s 601st Photo Flight at Thailand’s Takhli Royal Air Force Base.

Much of Wilson’s year in Thailand, from 1969 to 1970, was spent snapping photos from supersonic F-105 Thunderchiefs, known to their crews as Thuds. It has been said that the nickname derived from Chief Thunderthud, a character in the children’s comedy television series “Howdy Doody.” As big as they were—a Thud could deliver a heavier bomb load than a World War II B-17 Flying Fortress—the F-105’s cockpit was notoriously cramped and frequently reeked of jet fuel. Pulling Gs while strapped in with three or four cameras, a survival knife, and a revolver with extra ammo made taking pictures challenging. The design of the Thud’s canopy didn’t help; it produced so much glare that at times Wilson was blinded. To get his shots, Wilson would sometimes tape off part of the canopy with strips of black cloth.

One mission was particularly harrowing. Returning to base, the F-105 made what Wilson describes as a “hard landing.” He remembers smoke in the cockpit, foam on the runway, the pilot getting sick to his stomach. Ground crewmen had to pull Wilson out.

Now 68, Wilson eventually ended up in the insurance business in Columbus, Ohio. He says he still has nightmares about his war experiences, and suffers from post-traumatic stress.

**********

As with the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, all of which fielded their own cameramen, Air Force commanders recognized the merits of photographing and making movies of the war, if for no other purpose than to venerate the heroism of its aircrews. But the Air Force derived a particular value in visually recording the fighting: Fresh pictures and footage could be used to assess tactics and how best to kill the enemy.