The Flight That Changed Everything

When the 707 gave us the world.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/2a/692a02c6-70df-4dc7-8521-d5bbfc0009b4/05d_fm2019_707infographicnasm14338h_live.jpg)

America’s youngest jet-setter was seven years old when he boarded a Pan American World Airways Boeing 707 in New York, headed to Paris. It was October 26, 1958 and along with his parents and two older sisters, Loren Hopkins was on an all-expenses-paid, two-week tour of European capitals. His mother won the trip after entering a contest printed on the back of a Kellogg’s cereal box.

“She always had a desire to see other places,” said Hopkins, now 68 and a farmer in Kinsman, Ohio, of his mother, Vera. But she’d married a farmer, and their livelihood did not promise a life of travel. “For my mother to fly on a jet plane was the adventure of a lifetime,” Hopkins said.

A U.S. Army band serenaded the flight’s 111 passengers that night in 1958 as they approached the air stairs leading to the jetliner at Idlewild Airport. Among them was a genuine celebrity, the actress Greer Garson, who’d won an Academy Award for her performance in Mrs. Miniver 16 years earlier. (On its return flight from Paris, that 707 would carry Frank Sinatra and Danny Kaye.)

“We walked to the airplane on a red carpet with flags on both sides,” Hopkins recalled of the rainy night. Floodlights accentuated the white aluminum airplane’s size: 140 feet long with a 130-foot wingspan. Its four Pratt & Whitney JT3C-6 turbojet engines were sleek in polished metal nacelles suspended below and forward of the wings, rakishly angled 35 degrees off of the fuselage.

An enormous blue globe was painted on the tail of the airplane named Clipper America just for the flight. This was a new logo designed specifically for the mid-century modern age the airline was ushering in with its jetliner, an emblem that promised travelers the world.

And though the 707’s impact on the world was as yet unwritten, Loren Hopkins had an inkling that things were about to change.

“Going on that trip when I was so young made me think, ‘Why not go wherever you want to go?’ ” he said.

“Suddenly the public was able to travel nearly two times as fast,” said Kelly Cusack, director of collections and curation at the Pan Am Museum Foundation in New York. “I don’t know if [Pan Am founder] Juan Trippe imagined the effects of all of this, but when the world is smaller and everything seems closer, we perceive the world differently.”

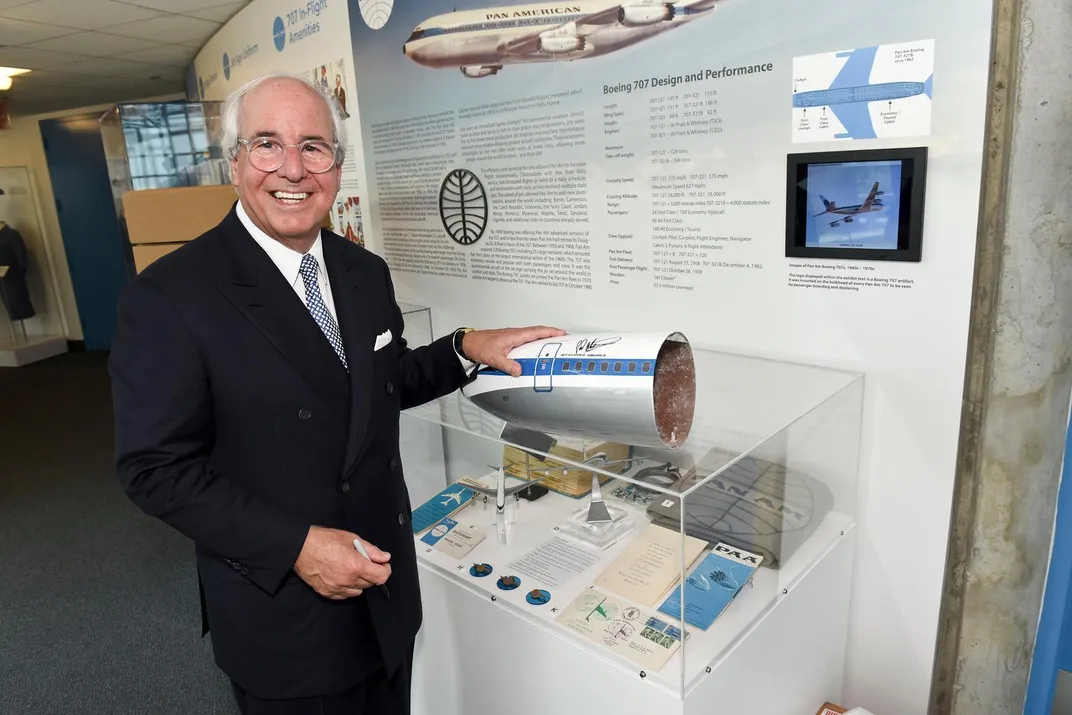

I spoke to Cusack last fall, two days after the foundation opened its permanent 707 exhibit at the Cradle of Aviation Museum in Garden City, Long Island, with a celebratory gala. The Saturday-night affair had a golden-age-of-aviation feel about it. Attendees not in cocktail attire were dressed in vintage Pan Am uniforms, the women in crisp blue stewardess suits and the retired pilots in white caps, navy blue blazers, and plenty of gold braid.

One guest not in uniform was Frank Abagnale, a 70-year-old businessman infamous for his brief but lucrative juvenile career passing himself off as a Pan Am pilot in the mid-’60s. Leonardo DiCaprio played the swaggering young impostor in the 2002 movie Catch Me If You Can.

The theme of the evening was Paris, the inaugural flight’s destination. An accordionist played during the cocktail hour, and cancan dancers performed during dessert. Though many former Pan Am staff were present, Loren Hopkins was the only person at the party who had experienced that slice of the airline’s history first-hand.

“When you took off, you could feel yourself going back into the seat,” Hopkins said.

Even the seasoned air travelers of the cabin crew were surprised by the 707’s power. Jay Koren, who would eventually publish a memoir about his 40 years of service with Pan Am, was called in to work the flight at the last minute when the airline decided to add a seventh flight attendant to the crew. He was 26 at the time. Koren, who died last year, recalled that first takeoff in an article he wrote for the book Pan American World Airways: Aviation History Through the Words of its People: “Even more startling was the unexpected vibration and violent roar of the jet engines as we gathered speed for our leap up into the night.” Sitting in the back of the aircraft in the jump seats with two stewardesses, he wrote, “We grasped hands and stared wide-eyed at one another in disbelief.” Koren would also be aboard the inaugural Pan Am 747 flight in 1970.

The luxuries aboard that 1958 flight—wines poured into stemware, hot meals served on china and set on linen-covered tables—likely went unappreciated by the seven-year-old Hopkins. But Boeing mechanic Steve Eastman and his wife Hazel were “googly-eyed,” according to their son, Hal, an executive-turned-fine-art-photographer in Washington.

Eastman, who died in 2007 at the age of 96, was an hourly worker in the ’50s, assigned to fabricate one-of-a-kind parts for prototypes, including some for the space program’s lunar lander and many for the Dash 80, the precursor to the 707. On July 15, 1954, after hearing the jet engines revving during a taxi run at Boeing’s Renton airfield near their home, the entire Eastman family jumped in the car and raced to see what was going on.

“It came roaring down the runway, and everybody cheered,” Hal remembered. His dad “was so proud. He was ecstatic. He drove us to where it was going to land, and we watched it make a perfect landing.”

The following day, Steve Eastman learned that Pan Am would be the first operator of the 707. He immediately booked two economy seats on the inaugural flight. He saved from his modest salary to pay for the trip he and Hazel would take four years later.

Boeing was well behind airplane makers in the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, who were already operating passenger jets. England’s de Havilland DH 106 Comet first flew in 1952 but was soon beset with structural problems that caused three of them to crash over a period of two years.

Russia’s Tupolev Tu-104 Camel had seating for 50 passengers, and when the Comets were grounded, it became the world’s only commercial jetliner between 1956 and 1958. But the Tu-104 lacked both capacity and range, according to Bob van der Linden, curator of air transportation at the National Air and Space Museum. He pointed out that Boeing’s third-place position allowed it to absorb the lessons of its competitors’ mistakes.

Inspired by the work of Germany’s Adolph Busemann, for example, the 707’s designers swept its wing farther back than the de Havilland team swept the Comet’s. De Havilland also embedded the Comet’s four engines in the wing, creating drag. Boeing had a more unconventional idea, which it first tested in its Dash 80 prototype and incorporated into the 707: It slung the engine pods beneath the wing. By doing this, the pylons guided the airflow over the wing on a straight path. On other swept-wing aircraft, the air would roll outward towards the wingtips. This could cause portions of the wing to stall and the airplane to roll. The Dash 80 and the 707 that followed did not have this problem because of the novel placement of the engines.

The 707’s first engine, the Pratt & Whitney JT3C was the commercial version of the military J57, which had won the 1952 Collier Trophy. The JT3C shared the axial compressor design of the Comet’s Avon jet engine but with a substantial upgrade: Two compressors—one low pressure and one high—fed air to the combustor and then to two turbines; again, one low pressure and one high. “The low-pressure spool is spinning slower as it builds the initial pressure up,” explained Mark Sullivan, author of Dependable Engines: The Story of Pratt & Whitney. “Then it goes to the high-pressure spool and is compressed yet again.” The remarkable two-spool engine produced 11,000 pounds of thrust, compared with the Avon, which produced 10,250 pounds.

Boeing was hard at work on the Dash 80 prototype that would soon become the KC-135 military tanker and the civilian 707, while across the Atlantic, de Havilland was struggling to fix the Comet’s problems and its reputation. When the improved Comet 4 was ready to fly late in 1958, with twenty-percent fewer seats than the 707, it was already an also-ran.

The legacy of the 707 and Pan Am’s influence on its passenger cabin live on even today in most single-aisle jetliners. Originally the cabin width of the Dash 80 would accommodate five seats, two on one side of the aisle and three on the other. First, the U.S. Air Force made Boeing widen the Dash 80 by 12 inches for the KC-135 tanker. But that still wasn’t wide enough for Pan Am.

“Juan Trippe reminded Boeing that Pan Am had just placed an order for 25 new DC-8s from Douglas that were six across,” van der Linden said. Boeing’s response was to widen its own airplane by four inches and add a seat.

If passengers felt the squeeze of the extra seat, they may have felt comforted by knowing they’d be in their seats for a shorter time. The 707 airspeed was nearly 600 miles per hour, roughly 200 mph faster than the Stratocruiser and DC-7 piston-powered airplanes it would replace, cutting New York-to-Paris flight times down from about nine hours to just a little over six. And of course there was the novelty of jet flight. For the seven-year-old Loren Hopkins flying across the Atlantic, the tipping point from thrilling to ho-hum came when he asked his mother why the airplane was moving so slowly. A stewardess overheard him and reported this comment to the captain, who came out into the aisle and invited the boy into the cockpit.

“That was the highlight of the trip,” Hopkins said. He was given a set of wings to put on his suit and a captain’s hat. “It was a size that fit my head.”

The Pan Am Foundation’s Cusack, an 11-year Pan Am employee and an inveterate collector of the airline’s memorabilia, was nevertheless surprised as he assembled the display at how expansive the airline’s story was. As Pan Am’s 707s began turning up in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and South America with their recognizable white and blue livery, they became the preferred mode of transportation for foreign dignitaries as well as for Americans on international business. The U.S. Air Force also bought three 707s, assigning one of them to the service of President Dwight Eisenhower.

The first Pan Am 707, tail number N711PA, left the fleet in 1974, and many airplane spotters believe it to have been destroyed. But among the attendees at the gala were two businessmen who have a 42-foot section of the next best thing: the Boeing 707, which in 1983 flew a special reenactment of the first Pan Am transatlantic flight.

Ward Wallau and Milan Micich operate Tokens & Icons, a company that turns pieces of sentimental artifacts like Major League Baseball bats and New York subway tokens into bottle openers and cuff links. When Micich tracked down an intact section of the Pan Am Clipper Emerald Isle at an airplane boneyard in Arizona in 2008, the men originally asked to purchase just two of the giant letters spelling out “Pan American” with the intention of cutting them up into several hundred sets of cuff links. But the historic nature of their find prompted them to reconsider. While they did sell dozens of the airliner’s windows as wall art (at $1,000 each) and many $180 cuff link sets made from the aluminum, they kept the “Pan American” script intact on a big chunk of the fuselage. It now hangs on the wall of their office in Berkeley, California. They’d attended the gala to try to determine whether the museum might be a more appropriate home for their treasure.

The Cradle of Aviation Museum exhibition demonstrates how Pan Am’s 707s reshaped the world beyond anyone’s expectations. It affected economies and trade, politics and culture, fashion and society. A section titled “Jet Age Woman” points out how Pan Am’s requirement that flight attendants be college-educated and (at minimum) bilingual helped move women toward greater social and financial independence. (Pan Am also held them to strict rules governing their appearance and behavior in ways that would never fly today, of course, but the arrival of a generation of women who traveled the world and earned decent salaries remains notable.)

The air cargo display, meanwhile, shows how the advent of the 707 altered global eating habits. Jet freighters could move perishable goods so that agricultural products were no longer geographically isolated. “Who ate Chilean sea bass in the ’60s?” Cusack asks. “All those kinds of things came as a result of the jet age.”

Those kinds of disrupters were still in the future when Steve and Hazel Eastman boarded the 707 for their first jet flight in 1958. For a mechanic and a housewife, the opulence seemed overwhelming, their son Hal said. But it was people just like them who would most feel the effects of the revolution.

Commercial jet travel would very quickly become commonplace. The expansion in air travel during the prior few decades became an explosion, from 87.2 million passengers in 1957 to 4.34 billion in 2018, according to data provided by the International Air Transport Association.

The Hopkinses and the Eastmans felt history change that day in 1958. But it didn’t take long before the rest of us felt it too.