Three Days in a (Really) Stinking Airplane

The diesel engine that commanded an endurance record for more than 50 years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7b/02/7b029cd5-67eb-4808-8734-f40568e83100/12h_am2018_nam-a-48446-e_live-wr.jpg)

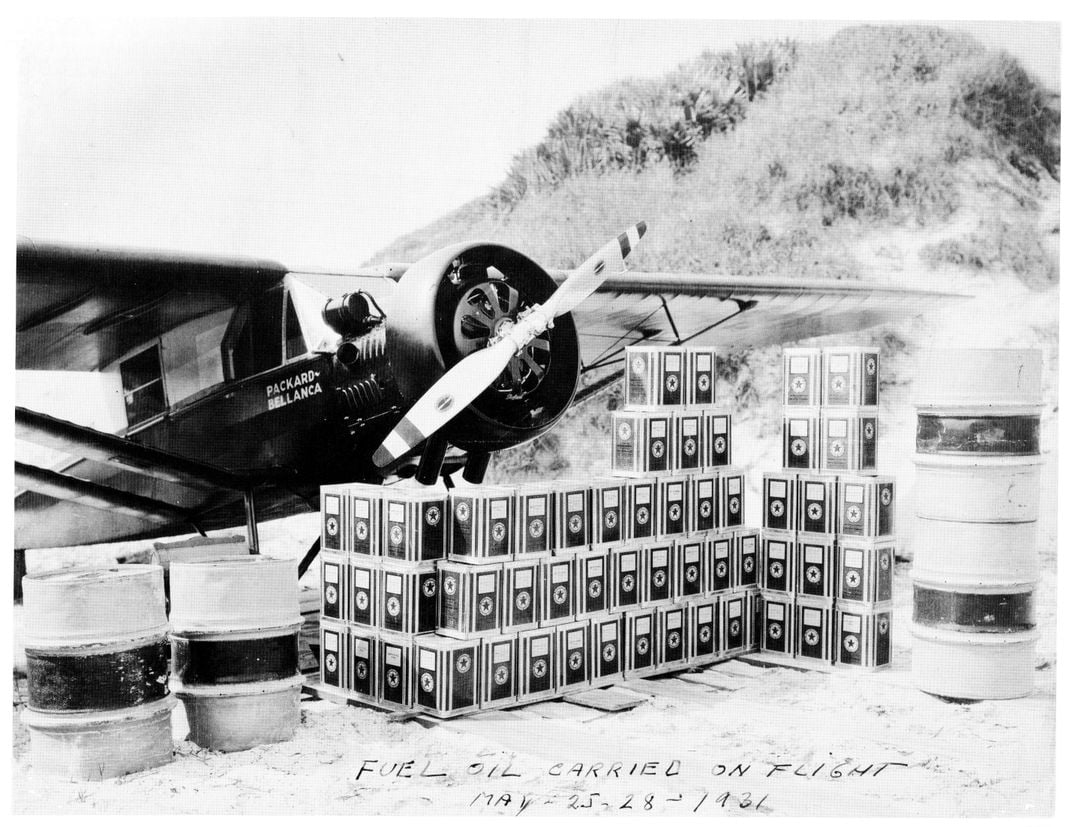

Early one spring morning in 1931, a strange metallic rain began to fall on Jacksonville Beach, Florida. A single-engine Bellanca-Packard flying laps above the beach was dropping empty five-gallon Texaco cans. The airplane’s two pilots were attempting to break the world aviation endurance record of 75 hours. By disposing of the cans as the fuel was used, the crew would eventually gain room enough to move about in the cabin and even sling a hammock. Rest would be essential: They were embarking in a cramped airplane on a flight they hoped would last a little more than three days.

Curiously, the fuel cans did not smell of gasoline. Instead, they contained a residue of No. 2 domestic heating oil. As the flight continued, the heating oil cans were intermixed with smaller tins of lubricating oil, which the crew was also burning as fuel.

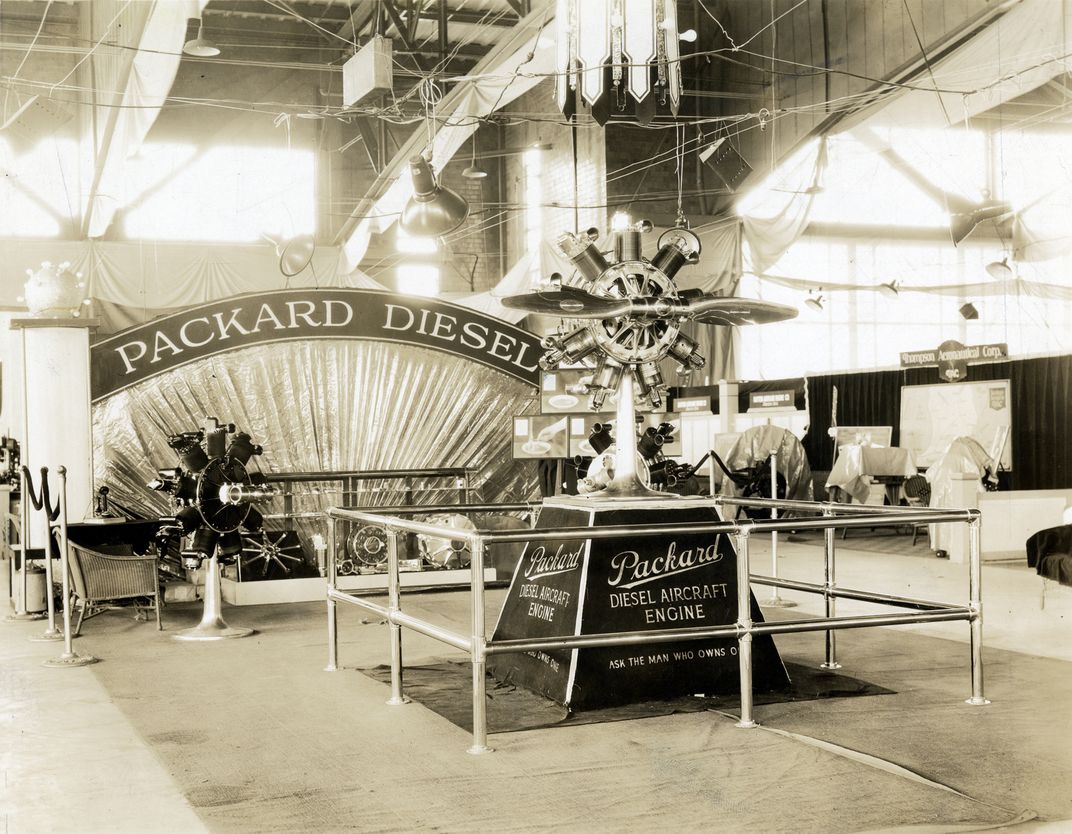

The unusual mix of fuels fed an unusual engine. The Bellanca had an air-cooled, 225-horsepower Packard DR-980 diesel, such an exciting development in aviation technology that it would earn Packard aviation’s most prestigious award, the Collier Trophy. The 1931 honor was presented to Packard representatives at the White House by President Herbert Hoover himself.

That achievement would also mark the high point for diesel engines in American aviation. Diesels have long been associated with heavy machinery, trucks, generators, and ships—anything but airplanes, which require powerful, economical, and, above all, lightweight engines. But today, with a convergence of economic and environmental incentives, the diesel airplane engine is again becoming viable. Several European companies have developed diesels for general aviation, and Continental Motors has introduced the CD-155, a piston engine that it claims runs on jet fuel or diesel, and can accept combinations of the two fuel types in any ratio.

Diesels were always efficient—as much as 35 percent more efficient than gasoline engines. And because diesel fuels are less flammable than gasoline, they are safer.

Seeing their benefits, German aircraft designer Hugo Junkers began developing a series of powerful, lightweight, two-stroke diesels during World War I and improved upon his design throughout the 1920s. By the 1930s and through World War II, these remarkable engines powered bombers, transports, and reconnaissance and maritime patrol aircraft.

Light but With an Aroma

In the United States, the Packard Motor Company led aero-diesel development by designing a smaller four-stroke radial engine. In 1928, before the first Junkers diesel had flown, Packard’s chief engineer, Captain Lionel Woolson, pushed the company to begin development of its own, very different diesel.

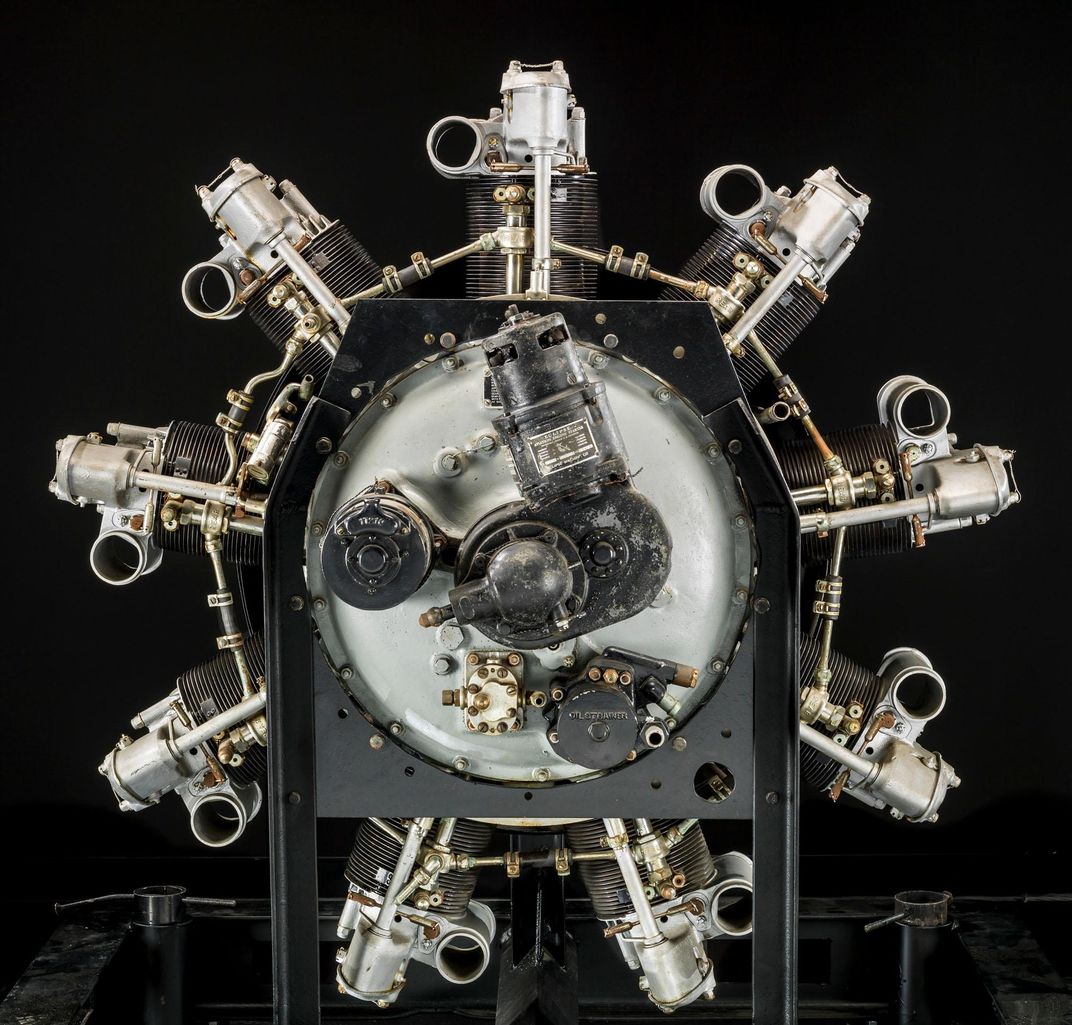

Working in conjunction with German engineer Hermann Dorner, Woolson conceived of a nine-cylinder, air-cooled radial engine, the DR-980, which employed the common four-stroke combustion cycle (intake, compression, combustion, exhaust). Woolson and Dorner managed to keep the DR-980’s weight so low that its power-to-weight ratio—2.26 pounds for every unit of horsepower—was only slightly more than that of contemporary gasoline engines. One of those weight-saving techniques was the employment of only one valve per cylinder, which would handle both intake and exhaust. The innovation had a downside: The exhaust gases contained considerable unburned fuel. The resulting stench and oily residue left passengers and crew dirty and smelling awful.

Nonetheless, the engine was efficient. On September 18, 1928, the DR-980 became the world’s first aero-diesel to fly, with Packard’s chief test pilot Walter Lees and Captain Woolson flying a re-engined Stinson SM1-DX Detroiter from Packard’s proving grounds in Utica, Michigan.

Lees and Woolson soon embarked on a series of long-range flights to showcase the engine’s economy of operation. On May 13, 1929, they flew the Stinson 700 miles from Detroit to the fourth annual meeting of the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics in Langley, Virginia, using $4.68 worth of fuel. The New York Herald Tribune noted the extraordinary measures Packard took to secure the engine’s secrets: Only journalists were allowed anywhere near the DR-980. No competitors.

On March 6, 1930, the Department of Commerce Aeronautic Branch gave the first type certificate for a diesel, rating it at 225 horsepower. Soon after, Lees and Woolson made a 1,100-mile proving flight, this time from Michigan to Miami, on $8.50 worth of fuel. Woolson once joked that with the diesel’s omnivorous appetite for fuel, it could run on melted butter. Indeed, during preparations for the first flight across Greenland’s ice cap, in May 1931, whale oil was seriously considered for use in an emergency.

The revolutionary engine was not perfect. Besides having a strong, unpleasant smell, it was loud and shook mightily as a result of the very high compression ratio employed. And in its earliest incarnation, the engine cylinders required pre-heating with blow torches on cold mornings. This cold-starting problem was later solved by the incorporation of glow plugs, but before that improvement, any airplane with a DR-980 under the hood was secretly warmed up in a hangar prior to the arrival of visiting dignitaries. The engine would be started before any visitors were allowed close enough to discover the trick.

The Record Campaign

Tragedy struck the program in April 1930 when Woolson, Packard’s principal advocate of the engine, was killed after crashing in a snowstorm. The confluence of Woolson’s death and the Great Depression moved Packard to abandon the DR-980 program. But the company refused to abandon Woolson’s attempt at the world’s unrefueled endurance record, something the man had pushed for before his death. At the time Packard began preparations, the record stood at 67 hours, but it was eventually extended to more than 75 hours by French pilots Lucien Bossoutrot and Maurice Rossi, flying a Blériot 110 over Algeria.

To carry the massive fuel load required for a flight of more than three days, Packard chose to install one of its engines in a modified Bellanca J-2 Pacemaker. The Bellanca was larger than the Stinson Detroiter, its cabin spacious enough for two pilots plus fuel cans and engine oil. It had the same configuration as the single-engine, high-wing monoplane Stinson, but the Packard team gave it a larger wing, a solid landing gear, and low-pressure tires for operations on sand. In essence, the Pacemaker became a diesel engine attached to an immense fuel tank: At 2,400 pounds empty, the Bellanca flew at a gross weight of 6,991 pounds, 3,949 of which was fuel and oil.

The Crew

The two-man crew was led by test pilot Walter Lees, 41, who had been flying since 1912. He’d been trained by Glenn Curtiss and held Aero Club of America license no. 44. He had an even lower number in the Caterpillar Club—no. 7—meaning only six before him had made the emergency parachute deployment required for Caterpillar membership. Lees jumped from an altitude of 150 feet.

With his impressive credentials, Lees was somewhat resentful of Charles Lindbergh, a much younger and less experienced pilot. While Lees had struggled, Lindbergh had achieved fame and fortune for a single flight. As if to rub salt into the wound, when the great Lindbergh test-flew the Stinson Detroiter diesel, with the older pilot relegated to the copilot’s seat next to him, he didn’t say a word to Lees. Achieving the endurance record would bring Lees the validation he craved, and perhaps settle a score.

His copilot, Fred Brossy, was, like Lindbergh, younger and less experienced. But Lees praised Brossy’s flying skills and, just as essential on a long flight, his easygoing temperament.

The pair loaded their Pacemaker with equipment and took off for Jacksonville Beach, Florida, the starting point for their attempt at the record. They’d chosen the site for its good weather and the long, smooth beach runway it offered for the grossly overweight takeoff.

Their preflight chores included carefully filling the five-gallon cans with Texaco’s No. 2 heating oil. They took care to load the cans in such a way that they would not shift in flight, or crush the pilots in the event of an accident.

To fuel their bodies on the first attempt, Lees and Brossy brought from their favorite local restaurant five fried chickens and 36 peanut butter-and-jelly sandwiches. They soon discovered that hours in the loud, shaking, stinking cockpit left them with little appetite. For subsequent flights, they reduced their rations substantially.

The pilots had created a checklist of conditions for a record attempt: light winds straight down the beach, a forecast of three days of good weather, and a smooth beach surface at low tide that would serve as a wide runway. It was March 11 when the proper conditions at last appeared. Before dawn the pilots, team members and record observers from the National Aeronautic Association assembled.

Preceded by a motorcycle policeman, the overweight airplane ponderously accelerated down the three miles of beach. The sand and rigid landing gear held firm, and after a 3,000-foot roll, the Pacemaker slowly rose into the air shortly before 9 a.m.

In an effort to spare the engine as well as to conserve fuel, Lees gently climbed straight ahead for five miles before, at 800 feet, beginning a delicate turn back toward the observers. Climbing at a glacial 1,000 feet per hour, Lees finally leveled out at their chosen cruising altitude—3,000 feet—where he throttled back to the minimum power setting that could maintain the altitude. The initial cruise speed was about 70 mph, but as they burned fuel and became lighter, the crew steadily reduced power, eventually bringing their speed to as low as 50 mph.

The crew now settled down to the monotonous routine of flying laps around the NAA’s ground observer station, from which the airplane was to remain fully visible. Thirty hours into the flight, an oil leak and temperature and pressure gauge failures made them abort the attempt.

After a month’s wait, the crew made a second attempt at the record on April 12. Aboard the aircraft were 458 gallons of heating oil costing a princely $45.80. Thirty hours in, they’d drained the wing tanks and moved on to the five-gallon cans in the cabin. After 45 hours, they had cleared enough room to sling their hammock. Before that, they had tried to sleep in their seats, leaning against foam pillows.

At about 4:30 a.m., a drizzle swelled into downpour. Visibility became so bad that the men were compelled to descend to 500 feet and circle the beach floodlight to maintain their orientation. They finally broke out of the clouds at dawn, but Mother Nature had not finished with them. Around 11 a.m. a fog bank rolled in off the Atlantic. Unable to remain in view of the observers as required by the rules, Lees decided to break off the flight and land 11 miles down the beach. They had been in the air a little over 74 hours. The flight would easily have set a U.S. duration record; however, because they had landed beyond sight of the observers, it could not be certified.

Another month passed before the weather permitted a third attempt. In the interim the engine was overhauled and a releasable 60-gallon belly tank was mounted to reduce the number of cans in the cabin while increasing capacity by 25 gallons. To compensate for the increased load, each pilot dieted and lost 10 pounds.

Finally, the Record

At 6:47 a.m. on Monday, May 25, the omens were good: clear skies and a light breeze. Lees took the stick, leaving Brossy to empty cans and hand-pump fuel and lubricating oil into their respective tanks. As the flight neared its end they also began to pump 15 gallons of excess engine oil into the fuel tanks. By mixing it with fuel oil and taking advantage of the diesel’s ability to run on virtually any hydrocarbon, the crew could extend the Bellanca’s endurance.

Previously, they’d burned the fuel in the new, detachable belly tank—which, due to a malfunctioning latch, had remained affixed to the Bellanca 12 hours longer than needed. Disposing of the cans was no easier: They had to be dropped in such a way that they would not strike the horizontal stabilizer. Brossy would put the airplane into a gentle dive while Lees held the can as far out as possible before releasing it to fall into the water in sight of the observers.

The observers would then fish out the cans and remove the attached linen tags that contained logs of fuel consumption, rpm, and speed, as well as notes for ground crew and family. During their two prior flights, the two pilots had become skilled bombardiers and lost only one tag, to a hungry dolphin.

About 50 hours into the flight, Lees looked out to discover a five-gallon can jammed between the left stabilizer and its lower strut. As long as the can remained it was at risk of flying into the stabilizer. When violent maneuvering failed to shake it loose, Lees had to try something more athletic.

With Brossy flying, Lees removed his parachute harness and, with a knife, needle, and thread, gingerly crawled down the fuselage toward the can’s location. All the while, he was monitoring Brossy’s ability to maintain control with Lees’ 160 pounds steadily moving the center of gravity aft. When he reached the can, Lees used the knife to slice open the fuselage’s fabric covering and pull the dented can free. With one hand he sewed the fabric closed again; finally, exhausted, he returned to his seat.

Throughout the flight the crew was receiving 4 p.m. briefings of the coming night’s weather. Lacking a radio, the message was delivered by means of a forecast written on the side of a Great Lakes biplane owned and flown by the NAA’s official observer, Ralph Greene.

Around 10:30 on the morning of the third day, Brossy awakened a napping Lees in the hammock. He was puzzled by a large smoky fire on the beach and the sight of cars racing about on the sand. The dazed pilots soon understood: After months of effort and days of flying, they had finally broken the record. After quietly shaking hands and making a logbook entry, they stolidly resumed their tasks, intending to press on as long as they could. However, as dusk approached, threatening weather led them to land early, with some four hours’ worth of fuel remaining.

Knowing they’d be photographed, Lees and Brossy tried in vain to make themselves presentable. They had shaved and washed daily, and now they changed shirts and donned ties—a natty bow tie in Lees’ case. The photograph of them shortly after landing shows two exhausted, filthy pilots flanking a solemn, white-suited Greene. He is holding the barograph that had documented their extraordinary 84-hour, 32-minute flight. They had beaten the record by more than nine hours.

Though they never garnered Lindbergh’s notoriety, the two were féted at receptions and in the press. But it was the engine that received the lion’s share of the praise, crowned in 1932 by the president’s presentation of the NAA’s Collier Trophy. Packard pointed out that while the exact distance flown was not precisely known, it would have been about 6,600 miles, or enough to fly to Europe and back. A Bellanca advertisement suggested Florida to Japan.

This was to be apex of the DR-980’s ascent. Not long afterward, Packard canceled the engine. But the record Lees and Brossy had used it to set stood for 55 years. Not until 1986 was it finally broken, when Burt Rutan’s Voyager made an unrefueled circumnavigation of the world.

It almost certainly smelled better than that diesel-driven Bellanca.