Aviation’s Sexiest Racer

Ettore Bugatti built fast cars—and just one airplane.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ba/3e/ba3ec2b4-3296-42d8-88eb-32f348c336e9/04c_sep2014_bugatti100p751_live.jpg)

The Bugatti 100P is the aviation world’s unicorn—an airplane so graceful and magical yet so rarely spotted that it’s passed into the realm of legend.

Built in the late 1930s by the most renowned race car manufacturer in France, it was an Art Deco masterpiece designed to set records at speeds above 450 mph. Virtually every aspect of the airplane broke new ground. The slender, streamlined fuselage housed a pair of supercharged straight-eight Bugatti Grand Prix engines powering contra-rotating propellers. The wings swept forward, not back. The empennage was shaped like a Y, with a V-tail and a ventral fin, and the elevators doubled as rudders. There was even an automated flight control system—an analog computer, if you will—that was meant to prevent the pilot from making a fatal mistake.

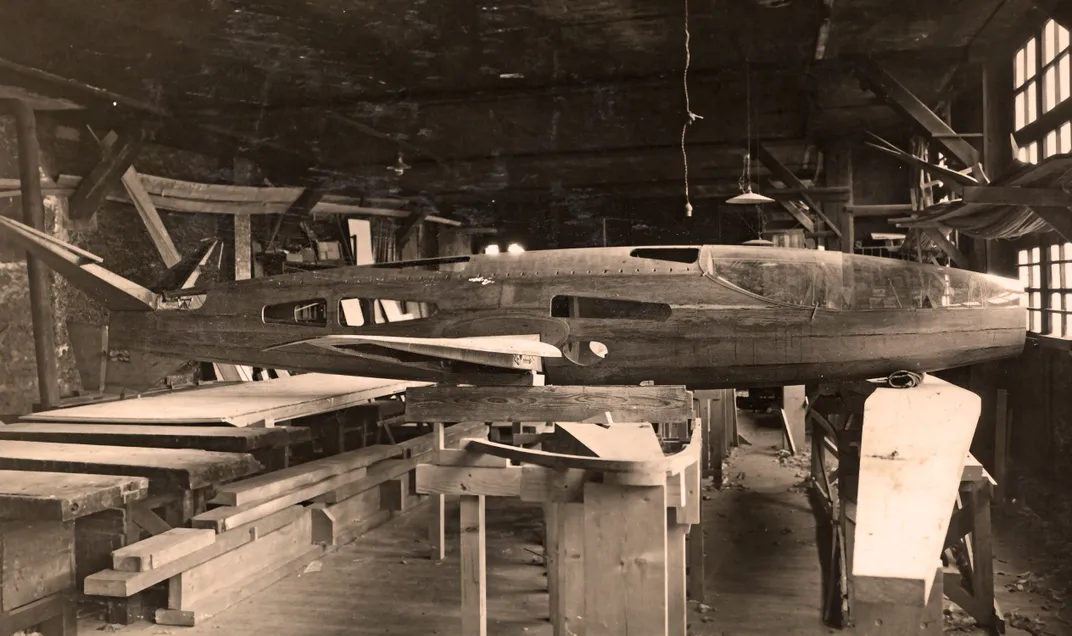

But before the airplane could be finished and flown, World War II erupted, and the Bugatti became one of the great what-if stories in the history of aviation.

About 40 years ago, Scotty Wilson was embarking on a career as an Air Force fighter pilot. While killing time in an operations room in Tucson, he read an article about the Bugatti, and he was dazzled by its shape, style, and technological audacity. Wilson went on to amass 4,500 hours in F-100s, F-4s, and F-16s (and 6,500 hours in everything from Piper Cubs to corporate jets), but he never got the Bugatti out of his mind. He learned that the airplane had survived World War II, broken down into pieces that were hidden to prevent the aircraft from being discovered by the Germans. Later, it came to the United States and was restored for static display. Today, it hangs from the ceiling at the Experimental Aircraft Association’s AirVenture Museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

Wilson believes that the 100P saga will not be complete until the design is airborne. In late 2008, he emailed a letter to the editor of Pegasus, the online newsletter of the Bugatti Aircraft Association. “We don’t need to know everything before we start doing something,” Wilson wrote. “This letter, then, is both a request for help and a call to action.”

Wilson was determined to build and eventually fly a faithful, if not fully authentic, replica of the Bugatti. No plans of the airplane had ever surfaced, and although much of the original airframe still existed, there was still lively debate over how some components fit together and even how they operated. And these were the least of his problems. Although Wilson has an A&P—airframe and powerplant—mechanic’s certificate, he cheerfully admits that “when my friends see me with a wrench, they call the police.” As for carpentry skills—a necessity for building what’s primarily a wooden airplane—Wilson scored zero out of ten. “I’d never built anything,” he says. “I’d never even built a birdcage. But I didn’t care how long it was going to take or how much it was going to cost because, one way or another, I was going to build this airplane.”

In May 2009, Wilson bought three eight-foot-long tables, joined them together, overlaid a grid of 100-millimeter squares, and started working. Not by himself. Core members of Le Rêve Bleu—The Blue Dream—team can be found in Great Britain, France, Belgium, Brazil, and the Netherlands. Wilson estimates that the project has consumed more than 10,000 hours and burned through $400,000 (some of it raised through Kickstarter). Working in a hangar in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where the temperature has ranged from 112 degrees to below freezing, he’s made most of the parts at least twice, many of them three times and some four, to get them just right. But now, on a bright, brisk day in February, the airframe is finally complete, and I’m on my way to Wilson’s shop to meet him and see his handiwork.

When Wilson opens the door, I start to speak, but he holds up his hand and says, “Before you ask me any questions, I want you to just look at the airplane.”

I turn and behold an object painted a shade of royal blue so deep it’s almost purple. The airplane is magnificent, a stunning combination of old school and new wave, a V-tail Beech Bonanza crossed with the X Fighter flown by Luke Skywalker, an antique that seems like it somehow came from the future. All I can think is Wow.

Attached to the wall of the hangar is a black-and-white photo of a man wearing the clothes of a bygone era. This, I assume, is Ettore Bugatti, founder of the Bugatti automobile empire. But when I get closer, I don’t recognize the face. “That’s Louis de Monge,” Wilson says. “No disrespect to Ettore Bugatti. But Louis de Monge is really the hero of this project. One of our goals is to resurrect him from obscurity. He deserves to be remembered for what he did with this airplane.”

De Monge was the aeronautical engineer who was primarily responsible for the Bugatti’s design. He isn’t so much a forgotten figure as one who never got his due. Born in Belgium in 1890, Vicomte Pierre Benoit Paul Marie Louis de Monge de Franeau began flying gliders from the family castle in his teens and built his first successful powered airplanes in his 20s. In 1921, a biplane racer he designed reportedly went 198 mph during testing—faster than the world record. But when the lower wings were removed, the sleek monoplane suffered from high-speed flutter and crashed, killing the pilot. Still, de Monge continued to explore avenues far from the mainstream, filing patents for automatic flight control systems and experimenting with flying wings. One of them, coincidentally, was fitted with Bugatti engines.

Ettore Bugatti was an Italian native who spent most of his adult life in France, and his company built cars that were elegant as well as fast. During the 1920s and ’30s, Bugattis won countless races, from the Monaco Grand Prix to the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and his luxury cars were among the most opulent of the day. Bugatti also had a long association with aviation, starting with the aero engines he built during World War I. In 1936, he began exploring the possibility of chasing the flying speed record. He asked de Monge if he could take a pair of Bugatti engines rated at 450 to 500 horsepower apiece and design a record-setting airplane around them. After eight days of thought, de Monge told Bugatti that he could. Work on the 100P commenced the following year.

De Monge left no written record of the thinking that went into the airplane (though he made some intriguing remarks during an interview conducted late in his life, while he was working as an automotive engineer in the United States). But Wilson is convinced that de Monge adhered to the design philosophy espoused by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the beloved French author and World War II P-38 pilot: “Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.”

Some Bugatti design mysteries will never be solved. “There have been times when I looked at photos of the original airplane and said to myself, ‘Louis, what were you thinking?’ ” Wilson says. “But whenever I had a question, I did it the way de Monge did, and I’ve always been rewarded, because a couple of months later, I understood his reasoning. This airplane is a perfect engineering solution to the challenge of flying fast.”

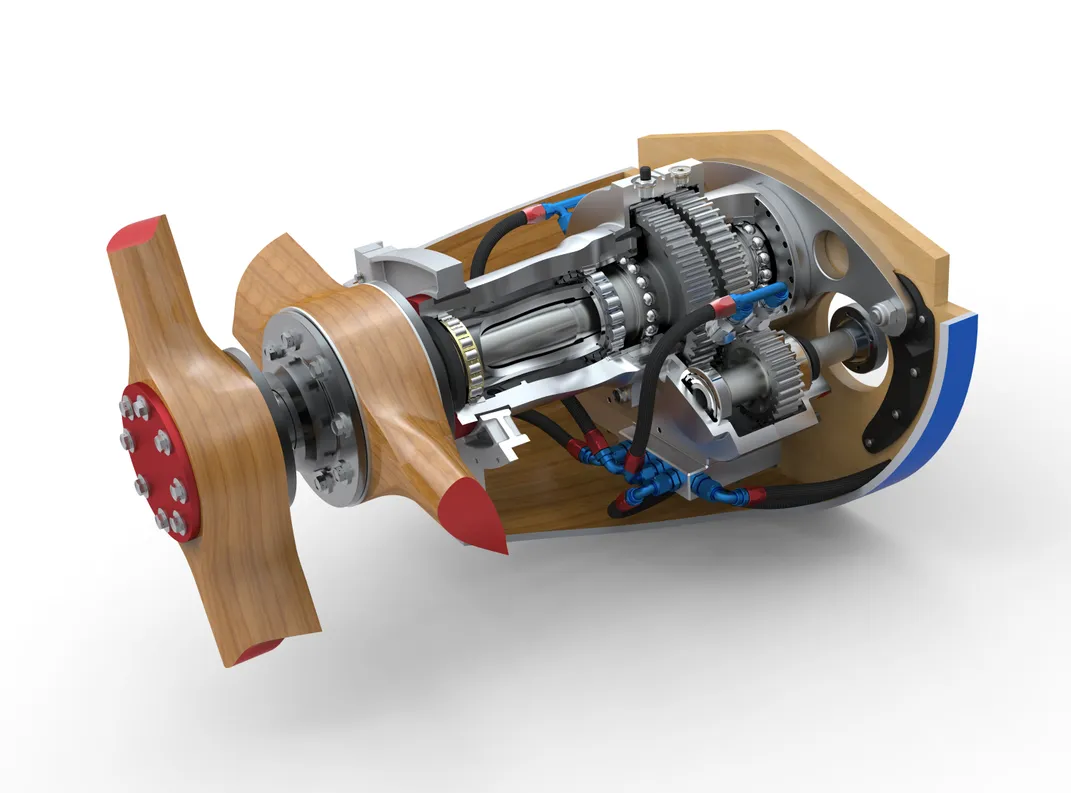

Compared to other air racers, the Bugatti was vastly underpowered, so de Monge had to make the fuselage as small and aerodynamically slick as possible. Burying the engines in the fuselage, one behind the other, enabled him to fashion a needle-nose semi-monocoque barely large enough to accommodate the pilot. Because they spun in opposite directions, the propellers canceled out each other’s torque and mitigated other control complications a single prop would cause. This allowed de Monge to design an aerodynamically clean V-shaped tail with a smaller-than-usual vertical stabilizer pointing down instead of up to support the tail skid. Air channeled into openings cut in the empennage was routed by ingeniously shaped ducting through internal radiators and out the trailing edge of the wing in such a way that it generated enough thrust to compensate for the drag produced by the cooling system—a phenomenon known as the Meredith Effect, later used famously in the P-51. Most startling of all was a system that tracked airspeed, manifold pressure, and throttle position, then automatically deployed the flaps and landing gear according to what flight regime (takeoff, landing, etc.) the airplane was operating in.

Bugatti got substantial funding from the French government in 1938, and construction continued even after the Germans invaded France. But in June 1940, with Paris about to fall, the airplane was disassembled and hidden on Bugatti’s estate. Bugatti died in 1947, having not resumed work on the 100P. The dismantled airplane passed through several hands before an American bought it in 1970 simply to get the rare Bugatti engines. The airframe was sold to Bugatti collector Peter Williamson, who started restoring it with the help of de Monge himself. But the project was never finished, and the Bugatti was donated first to the Air Force Museum Foundation and then, in 1996, to the EAA museum, which placed it on static display.

Once in the United States, no one made any plans to fly the Bugatti. Over the years, several enthusiasts talked about creating an airworthy replica, but all were stymied by a lack of money, knowledge, and drive. Then Wilson, freshly retired and looking for a challenge, charged in. “I knew that I didn’t know enough to finish the project,” he says. “But all I needed was enough to start.”

After four visits to Oshkosh, Wilson realized it would be impossible to copy the original airplane precisely. Still, he was determined to reverse-engineer it and produce a replica faithful to de Monge’s vision. This entailed incorporating the elements that grew out of five patents: for the composite-wood construction, the V tail with ruddervators, the drivetrain running through a bespoke gearbox, the first-of-its-kind cooling drag system, and the automated flight controls. Naturally, Wilson had to make some allowances for cost and safety. He opted for a composite wood called DuraKore (typically used in boats) rather than the original tulipwood faced in balsa, and he glued it with modern epoxy. Fiberglass replaced doped fabric, and magnesium—used liberally by Bugatti to save weight—was rejected because it is so expensive and flammable. Most notably, the engine bay will house a pair of Suzuki Hayabusa motorcycle motors rather than the glorious, but essentially unobtainable, blown Bugatti straight eights.

But within reason, accuracy was paramount. Early on, Wilson enlisted the aid of Jaap Horst of the Netherlands, founder of the Bugatti Aircraft Association and author of the book The Bugatti 100P Record Plane, and Frenchman Frederic Gasson, who built a remote-controlled version of the racer and a scale model that was tested in a French wind tunnel. Jean François Sibille, who’d apprenticed in the Bugatti design studio, vetted some of Wilson’s creations. Even de Monge’s grand-nephew, Ladislas, spent several months in Tulsa working on the project.

Wilson has an extensive network of local team members, including sheet metal artist T.J. Balentine and painter Daniel Davis. We get in a pickup truck with 180,000 miles on the odometer, and Wilson takes me around to meet some of the other team members. A lot of metal work is done at the oilfield compressor company owned by Vince Thomas, who has several vintage airplanes. Brooks Thompson, a 79-year-old race car builder, helped solve some of the problems posed by the extra-long driveshafts. Jeff Lewis, a bearded machinist whom Wilson calls “the single most important person on the project in the United States,” works out of an incredibly crowded garage with a 1977 Bridgeport mill that’s still running DOS. Most machinists prefer to have CAD (computer-aided design) drawings that can be plugged into milling software. Not Lewis. “I tell Jeff what I need,” Wilson says. And Lewis says, “And I give him the drawing.”

The one-of-one gearbox, though, required a different approach. This was the most complicated—and costly—piece of the puzzle, and Wilson knew that it was a potential showstopper. Fortunately, he found John Lawson, an ex-Royal Air Force mechanic. Or, to be more accurate, Lawson found Wilson. The Brit had become fascinated by the airplane; “When I Googled the Bugatti,” he recalls, “I discovered a lunatic in Tulsa who was endeavoring to build it. So I emailed him.”

An industrial modeler by trade, Lawson agreed to take a whack at the gearbox. “Originally,” he says, “I thought I could do it in a week or two.” The process ended up taking him 3,000 hours.

It’s now March, and Lawson and I are chatting at the Mullin Automotive Museum in Oxnard, California. Owner Peter Mullin has been fascinated by the 100P ever since he drove his Bugatti Type 57 to Oshkosh and saw the original airplane. When he started putting together an “Art of Bugatti” exhibit, he wanted to include Wilson’s replica. Wilson agreed, though it pushed back the first flight until late this year.

Wilson says that after the Bugatti leaves the museum, it will take 60 to 90 days to install the engines and get the racer off the ground. He has no intention of setting any records; all he wants to do is fly the 100P long enough to prove the concept. Because de Monge designed the airplane solely to go fast in a straight line, Wilson expects it to be pitch-sensitive and just marginally stable in yaw. Says Paulo Iscold, a Brazilian aerospace engineering professor who had his students analyze the 100P: “Flying it should be no big deal, but I don’t think it will be easy to fly near the ground.”

At the moment, Wilson is here in Oxnard for the media preview of the museum exhibit. He gazes at the 100P as it sits in the exalted company of automobiles collectively worth more than $100 million. “I can’t believe that we’re here in this museum,” he says. His excitement is palpable.

And that is how a lot of people will feel when—if all goes according to plan—Wilson eases back on the control stick and the Bugatti rises from the runway. Somewhere, Louis de Monge and Ettore Bugatti will be beaming.