How a WW2 Combat Injury Led to a Treatment for Cataracts, 40 Years Later

WW2 ace Gordon Cleaver’s doctor came up with a technique that has saved the sight of millions of people.

:focal(423x214:424x215)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0c/2e/0c2ee311-44eb-45cb-90a6-5500ac7db0bc/18c_dj2017_hurricanemk1laterinwar_live-wr.jpg)

Gordon “Mouse” Cleaver was one of the first Royal Air Force aces of World War II, but his most indelible mark on history was inadvertently inspiring a surgical procedure that has saved the sight of hundreds of millions of people.

Cataracts—natural clouding of the lens of the eye—are the most common cause of blindness. For thousands of years, the only treatment was an excruciating technique known as couching, in which a needle-like instrument was used to push the lens out of the line of sight. In 1747, French physician Jacques Daviel pioneered the practice of surgically removing clouded lenses—eliminating cataracts was better than nothing, but it was obviously an imperfect solution.

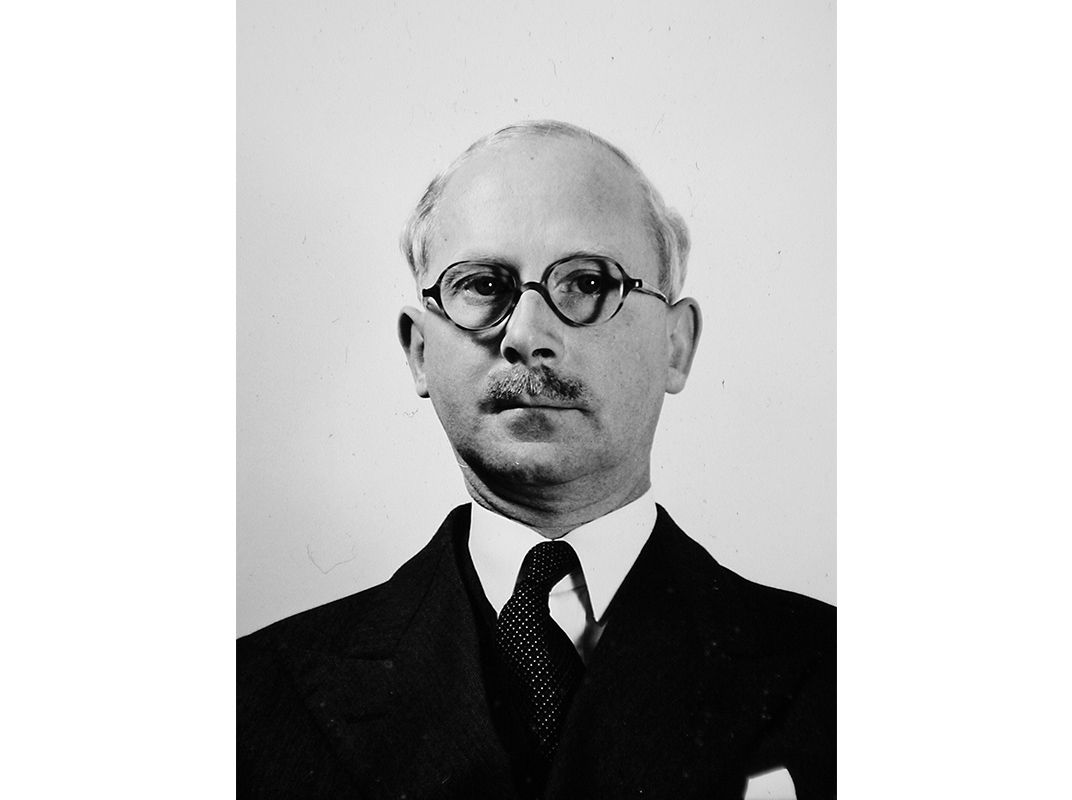

As a freshly minted physician in the 1930s, English ophthalmologist Harold Ridley first broached the possibility of replacing clouded natural lenses with clear artificial ones. But his mentor rebuked him, and after Germany invaded Poland, Ridley’s thoughts turned to the fighting to come.

Mouse Cleaver was a member of the No. 601 Squadron, known informally as the Millionaires’ Squadron because so many of its pilots were upper-crust British sportsmen. By the time World War II began in earnest, the 601 was flying Hawker Hurricanes.

Cleaver was dispatched to France with the rest of his squadron in May 1940, a week after the German blitzkrieg commenced. Two days later, he scored his first victory, claiming a Dornier Do 17. Then it was back to England, where Cleaver fought in the Battle of Britain.

On the morning of August 15, 1940, Cleaver flew an uneventful sortie. During lunch the unit scrambled again. In his haste, Cleaver forgot his goggles.

While lined up behind a Junkers Ju 88 over the city of Winchester, Cleaver’s Hurricane was raked with machine-gun fire. His airplane burst into flames, and acrylic shards from the shattered canopy lodged in his eyes. Burned and bleeding, he flipped the airplane upside down and let himself fall out of the cockpit, then parachuted safely to the ground.

Cleaver’s right eye was too badly damaged to save, but he underwent 18 operations to treat his facial wounds and restore some vision in his left eye. (His first comment, when he was visited by a squadron mate, was “Jack, tell them all to wear their goggles.”) He was examined repeatedly by Dr. Ridley, who made a stunningly counterintuitive discovery.

Other than damaging the lens, the plastic splinters in Cleaver’s left eye had no effect on his sight, and his body made no attempt to reject them. This nudged Ridley into thinking about using a plastic lens to replace the natural one removed during cataract surgery.

On November 29, 1949, Ridley implanted the world’s first IOL, or interocular lens. Lamentably, instead of embracing this immensely successful procedure, the medical establishment ridiculed Ridley and rejected IOLs. It wasn’t until the 1980s that IOL implants became commonplace; nowadays, 20 million such operations are performed annually, and the number would be much higher if the surgery were more widely available.

In 1986, Ridley was belatedly elected to the Royal Society, the British version of the National Academy of Sciences. And in 1987, the story came full circle when Mouse Cleaver had cataract surgery and received an IOL made of a material remarkably similar to the acrylic that had lodged in his eye in 1940.