The First Airplane to Cross an Ocean

A family photo album of a landmark in aviation history.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/a2/bea258a0-5749-49ad-bc53-62449417e614/nc4.jpg)

Sometimes we hold history in our hands and don’t know it.

As a five-year-old, Todd Ryan lived with his grandparents at their house in Queens, New York City. He often joined his grandfather, Gene Smyth, in his carpentry shop. “Instead of saying, ‘Don’t touch that,’ ” Ryan recalls, “he’d say, ‘Let me show you how to do that.’ ” He also recalls spending hours leafing through an airplane-spotting book in the house and then drawing pictures of images in the book.

The day after Ryan turned six, his grandfather died. Ryan eventually inherited his tools, a gift he still treasures to this day. Ryan later became a photographer, graphic designer, private pilot, and skydiver, as well as an avid aviation history buff. “He set me on a path,” he says of the time he spent with his granddad. That path has come full circle.

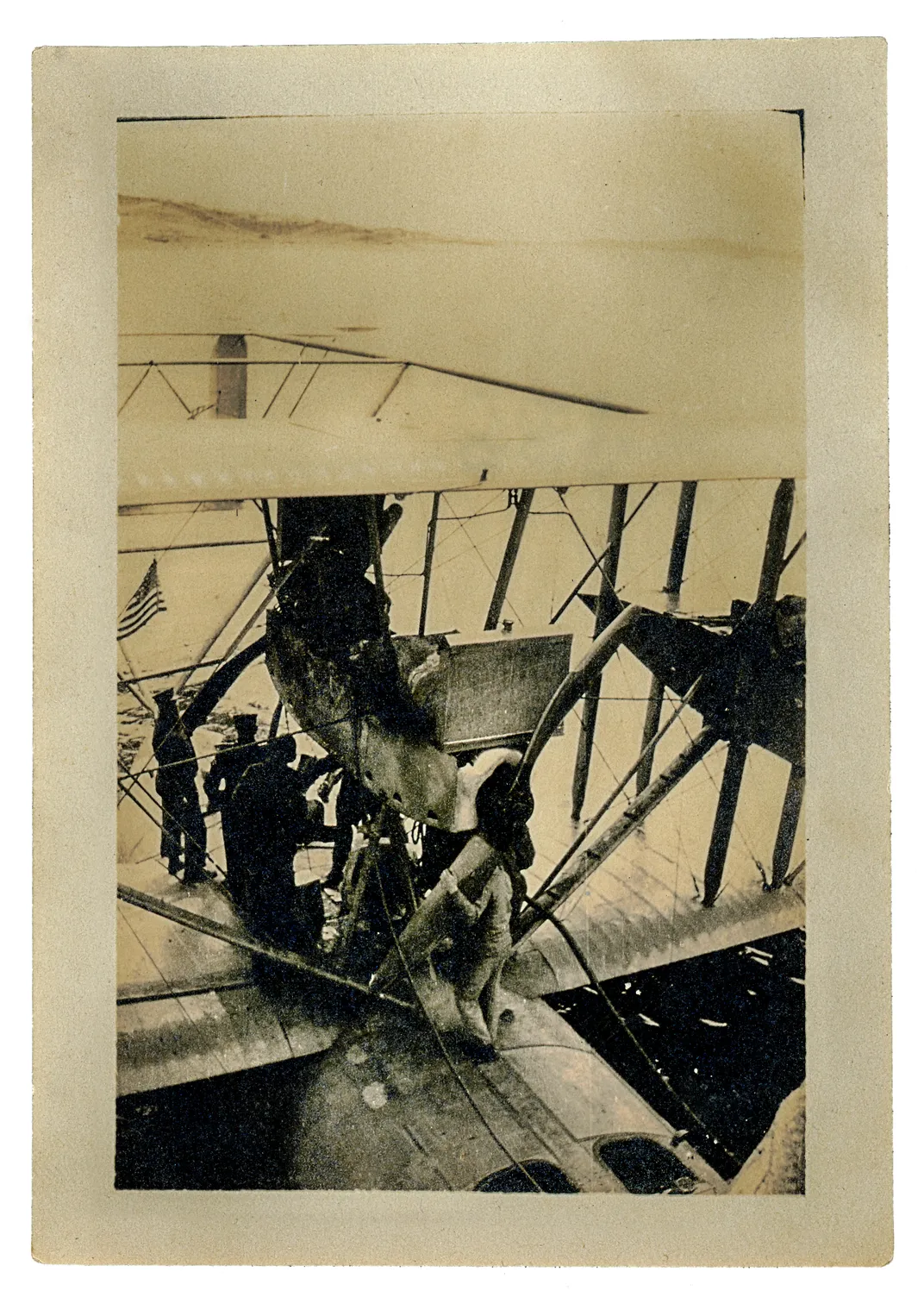

While clearing out his mother’s house last year, Ryan, now 67 and living in Colorado Springs, came upon another treasure his grandfather left behind: a yellowed envelope containing a handful of small, black-and-white photographs. In one is a large flying boat. In another, his grandfather sits at the front of a large crew of sailors, some holding a large propeller with “Carpenter Gang” painted on it.

“Nobody had seen the pictures in almost 100 years,” Ryan says. He looked closely at one of the flying boat pictures. He could see the number “1” on its hull. “I knew immediately what it was. When I saw that, I thought, ‘Wow!’ ”

* * *

The photos revealed something he never knew about his grandfather. Smyth had played an important if unsung role in one of aviation history’s iconic events: the first flight across the Atlantic Ocean, a milestone that took place a century ago.

On May 8, 1919, three U.S. Navy flying boats took off from the water at the former Rockaway Naval Air Station outside New York City. They embarked on a great race against privately funded competitors to become the first aircraft to make the aerial leap over the Atlantic.

Designated Navy-Curtiss, or more commonly “NC,” for their joint Navy and Curtiss Engineering Company development, the “Nancy” flying boats—numbered 1, 3, and 4 (2 having been cannibalized for parts to repair damage the NC-1 had suffered in a storm)—flew to Halifax, Nova Scotia. From there they went to Trepassey, Newfoundland, before lighting out on the journey’s longest leg, across the Atlantic, to the Azores. Their flight plans called for them to continue from there to Lisbon, then Spain, and on to their final destination in Plymouth, England.

Today, it can be difficult to imagine the void that the ocean moat between North America and Europe represented a century ago. The anticipation surrounding the Navy’s transatlantic flight was comparable to the excitement on the eve of the Apollo 11 launch 50 years later.

The Nancys faced plenty of challenges. Originally the aircraft flew as tri-motors, but tests proved a fourth, breakdown-prone Liberty engine was needed. Even then, getting the 65-foot, mahogany-and-spruce hull—weighing 28,000 pounds and filled with 1,900 gallons of gasoline and five crewmen—off the water and then over 1,200 miles of ocean seemed foolhardy. Also, with their unreliable compass, sextant, and primitive radio, the aircraft could easily drift off course.

Hill Goodspeed, a historian at the National Naval Aviation Museum, walks by the NC-4 on display in the Pensacola, Florida, museum virtually every day. On loan from the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum since 1974, “it is the defining aircraft that visitors see when entering the museum,” he says. The Nancys were among the technological marvels of their day. “Other efforts were underway to fly across the Atlantic at the time,” Goodspeed says, with a big cash prize held out for the winner. But the U.S. Navy was determined to do it first. “The nation and the Navy wanted to re-establish American aviation prominence that the war had interrupted.”

But before the Nancys dared take off from Trepassey, they needed overhauls. That’s where Gene Smyth and his tools enter the story.

* * *

Ryan never had the chance to ask his grandfather about his military service, but his mother knew that he had served on board a World War I minelayer, the USS Aroostook. The ship had been converted into a seaplane tender after the war. The Navy sent it ahead to Trepassey as the designated “mothership” for the transatlantic mission. The 25-year-old Gene Smyth was Chief Carpenter’s Mate on board the Aroostook, in charge of the “Carpenter Gang.” They were responsible for every wood part on the Nancys. There were plenty of them. At Trepassey, they installed the new multi-ply oak props, replaced cracked mahogany planks in the hulls, and made sure that the spruce stringers, spars, and struts holding together the wings, forming the fuel compartments and cockpits, and mounting the engines were ready for the long flight.

When Smyth was not scrambling over the wings and through the hull, he pulled out his camera to take snapshots of the big event. “It must have been a point-and-shoot of the day with a fixed-focus lens,” says Ryan. “He might have shot one roll on the entire trip because of how expensive film was at the time.”

On the evening of May 17, 1919, the three Nancys roared up Trepassey Harbor and took off. Before they did, the captain of the Aroostook bet the NC-4’s commander, Albert Cushing Read, that he would beat him to Plymouth. Read lost the bet.

All went smoothly overnight, but weather, balky instruments, and high seas defeated both the NC-1 and the NC-3. After getting separated in the darkness and then lost in the morning fog, each landed on the open ocean to take bearings. Twelve-foot waves demolished the NC-1. Before it sunk, a passing freighter rescued the crew. The NC-3 had a rough landing that collapsed an engine mount, keeping it on the water. It taxied the final 205 miles to the Azores.

The NC-4 narrowly escaped spinning out in the dense fog and flew on. Shortly after noon, after about 15 hours of flying, Read brought it into the harbor at Horta in the Azores. The aircraft waited out repairs and weather before continuing on to Lisbon—Europe!—on May 20, becoming the first airplane to cross the Atlantic. Early in the afternoon of May 31, NC-4 completed the final flight stage, landing in Plymouth Harbor. A huge British crowd along with Royal Navy ships and aircraft welcomed the U.S. Navy flier. “Read of the NC-4 is the Christopher Columbus of the twentieth century,” declared one U.S. newspaper.

The Aroostook easily beat the NC-4 to Plymouth, and Gene Smyth and his Carpenter Gang were there to meet it when it landed. They broke down the NC-4 and took it on board to steam home. After leaving the Navy later that year, Smyth may have brought some of his tools home with him. A century on, his grandson, Todd Ryan says, “Many of the tools that I played with in my grandfather’s shop as a five-year-old I still possess. Who knows? Maybe the coping saw I use once cut stringers for the NC-4.”

And, of course, Ryan has the photos, taken on a day 100 years ago when aviation made the world a bit smaller.